On the Right Track

I’ve had a front-row seat witnessing and being part of the changes in the trade over the years

Having been in the studio recording business for a good few decades, I’ve had a front-row seat witnessing and being part of the changes in the trade over the years.

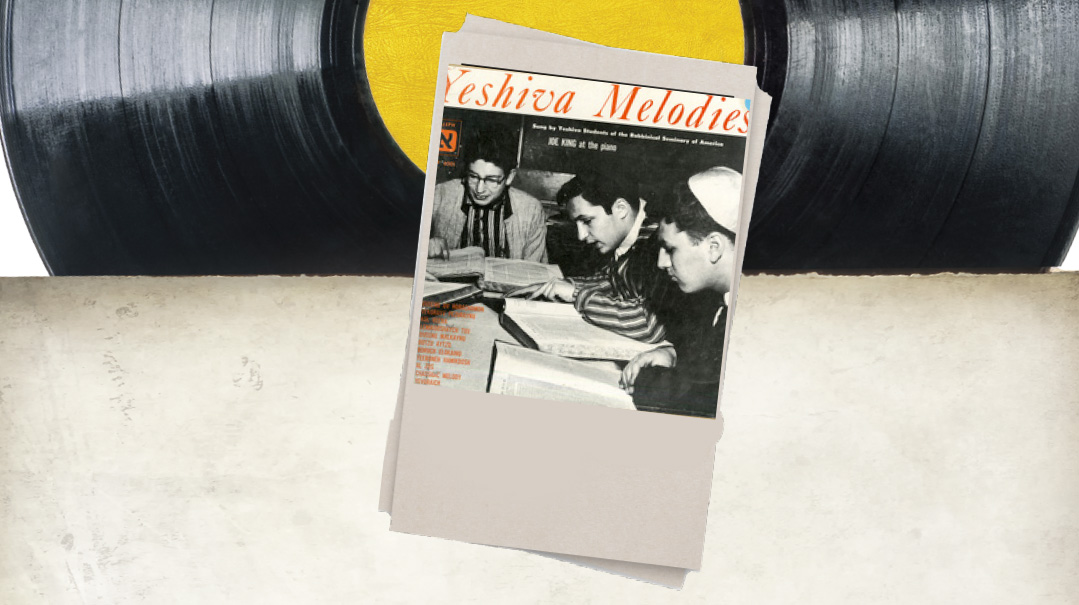

While I wasn’t around in the 50s and early 60s, I can tell you that recording back then was really not much different than recording a live event. All the musicians with their instruments, all the singers, all the choirs and vocalists had to be in the studio at the same time. The engineer would push the record button, and the singers and players would have to perform the entire song flawlessly. If somebody went off key or confused some lyrics, the entire song had to be rerecorded. MBD once told me that the engineers in the studios back then were always amazed by how his father, Chazzan Dovid Werdyger, always got it right the first time. They used to say that “The Cantor” was the quickest recording artist they had ever seen.

Those who were skilled to perfection could record an entire album in several hours, while others were busy over days and weeks. Dovid Werdyger’s musical conductor, Yaakov Goldstein, played a major part in his recordings, as he, too, played flawlessly and didn’t require extra takes. When it was all done, a good engineer could add reverb, echoes, and sounds to polish the end result and make it sound better. Aside from Dovid Werdyger, artists such as Shlomo Carlebach, Benzion Shenker, and Jo Amar, to name just a few, recorded in such a fashion in those days.

By the mid-60s, recording changed completely. The new way to make a record was to record on different tracks. Let’s say you were recording in a 16-track studio. You had eight musicians in the orchestra, and you recorded the song on eight different tracks; now, if the guitar player made a mistake, all you had to do was go back to the guitar’s track and rerecord his part, while the rest of the band remained untouched. You also didn’t have to record the entire guitar track again, only the part that had the mistake — even if it was only one note. This technique, called “punching in and out,” applied as well to the singer, the harmonies, and even the child soloist. So as long as the team members stayed on their own track, only their part had to be replaced.

It could sometime take as long as two or three hours to get one ten-second solo properly recorded. On the other hand, sometimes people had a bit of luck and got it on the first take. Dov Levine, whose nickname was “One-Take-Levine,” was known for getting it on the first take.

When recording, musicians had to be careful that their instrument didn’t “leak” onto another instrument’s track — that’s why the drummer played his part in a sound-proof booth. After the vocals and music were placed on separate tracks, it was the engineer’s job to blend it all together. Mixing a four-minute song could take anywhere from two hours to a full day — and for most people, it was cost-prohibitive as well. With the cost of building a professional studio close to a million dollars and the machine itself about half that (you could sometimes get a used one for less), studio time was out of range for many would-be entertainers.

About 25 years ago, the industry changed yet again, when so much of life — including recording studios — went digital. Today, artists record directly onto the computer hard drive. And they aren’t relegated to 16 or 24 tracks — the number is unlimited. Generally, one track is recorded at a time: piano, bass, guitar, and so forth. And since today, a good keyboard can nearly perfectly reproduce the sound of a live trumpet, trombone, and even drums, many recordings get an entire orchestra sound with just one musician — a keyboard player.

And not only that. If a vocalist was off key, the engineer can fix it with something called “auto-tune” while the singer is home eating dinner. They also have the option of changing the key to the entire song with just the push of a button. Another gamechanger is that, years ago, when the chorus was repeated multiple times, the singer or choir would actually have to sing it over and over. Today, it’s one time only, and then the engineer just repeats it over and over with the push of a button. This is called copying and pasting, just like on a word document.

Time zones and logistics are no longer an issue, even in recording a duet, especially helpful for guys like me working on all-star albums or multiple-voice recordings. I’d often record an Uncle Moishy narration together with Zale Newman, with me in New York and Zale in Toronto.

And what about those million-dollar studios? Today, with a good computer, a few mics and a talented engineer, you can have a studio in your basement for less than 10,000 dollars. Talk about buying something “for a song.”

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 982)

Oops! We could not locate your form.