On Shabbos the Senator Stays Home

T

he sun was tipping toward the horizon in the late-afternoon western sky. It would soon be Shabbos.

Earlier that day Al Gore and his running mate Joseph Lieberman had received news that temporarily gladdened their hearts.

It was Friday December 8 2000 — a full month after Election Day. The Florida Supreme Court had just ordered a recount of disputed ballots in the still-undecided presidential race. Nationwide the Gore-Lieberman ticket had outpolled the Bush-Cheney slate by more than 500 000 votes but the all-important Electoral College vote was so tight that whoever won Florida would be the ones to be sworn into the White House. Bush was clinging to a slight lead in the Sunshine State that Gore contended would be reversed in a recount handing him the victory.

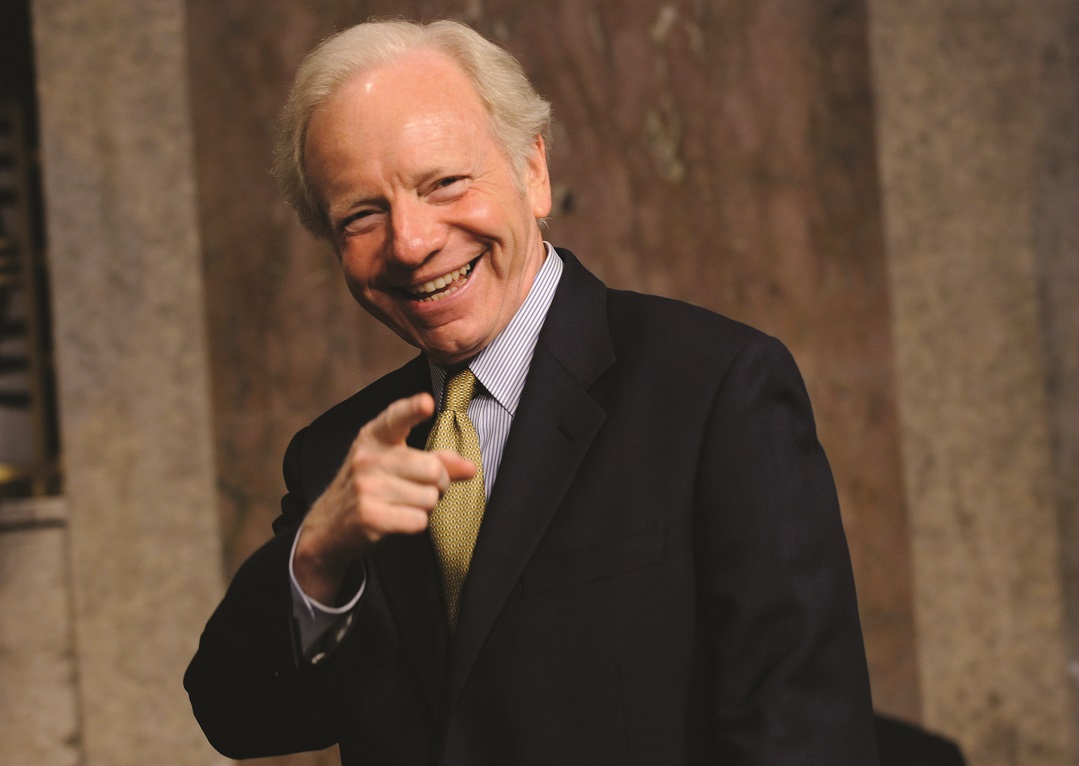

Joseph Lieberman a Shabbos-observant Jew and the first and only Jew to run on a national presidential ticket stood a few uncounted votes away from being elected vice president. He and his wife Hadassah were in their Georgetown home getting ready to take in Shabbos when Gore called on the phone.

“It’s not sunset yet is it?” asked Gore.

“No” answered Senator Lieberman.

Concerned that important legal decisions requiring consultation with his running mate were pending and knowing that Lieberman was shomer Shabbos and was unlikely to pick up his phone Gore invited the Liebermans to spend Friday night with them.

The Liebermans immediately packed up their Shabbos candles wine challah and dinner and headed to the Gores who lived about a mile away. The Gores made every effort to accommodate the Liebermans including providing a private room for Mrs. Lieberman to light Shabbos candles and a quiet corner for davening.

As the Liebermans walked home after the Friday night dinner Secret Service agents escorted them back to their Georgetown residence on foot.

As history played itself out the US Supreme Court overturned the Florida court’s decision no recount took place and it was George W. Bush and Dick Cheney who took the oath of office that January. And Joseph Lieberman remained in his seat as Connecticut’s US senator. It is the post he has held since he was first elected in 1988 and it is the position he is retiring from next year at age seventy following forty-two years in public service.

In August Senator Lieberman published his latest book: “The Gift of Rest: Rediscovering the Beauty of the Sabbath.” In it he relates many stories of how he has kept the Shabbos holy during his long political career as well as how his colleagues and not just Al Gore have been unswervingly solicitous in accommodating his religious beliefs.

“I would say that I’m not surprised but I’m never unappreciative and I don’t take it for granted” said Senator Lieberman in a telephone conversation from his Washington DC office.

Constantly Improving

Senator Lieberman, who began his political career in 1970 as a state senator in his native Connecticut, noted that from the very beginning, he had to turn down invitations to attend political and community events on Shabbos. While some people were puzzled, upset, or frustrated, eventually they accepted the condition when they saw that he was saying no as a matter of faith — and that he was consistent.

“It’s gotten much better over the years. The willingness of the American people to accept diversity of all kinds has increased,” said Senator Lieberman, who contends that his religious beliefs were a drawing card for voters in 2000.

“Obviously I don’t mean to relitigate the results, which were controversial. But the numbers say that the ticket I was on got a half million more votes than the other ticket. Politics and elections are like sports, where it comes down to numbers. It was a reflection of the willingness of the people in this country to judge people by their quality, their merit, as opposed to their religion. This remains a very religious country in which there is a kind of reflective respect for people of religion even if they’re not of their own religion,” the senator said.

If religion was a factor in Senator Lieberman’s 2000 race, it has been catapulted to a front seat position in the 2012 presidential campaign. Two Republican candidates, Mitt Romney of Massachusetts and John Huntsman of Utah, are Mormons. Texas’s tough-talking Rick Perry, a Methodist, has hardly been gun-shy about talking about religion. He was a leading light at a controversial prayer rally in Houston where he indicated that America might experience a more rapid recovery from its economic ills if the nation repented.

Senator Lieberman, in a recent interview with the National Review, you were quoted saying: “I like it when a candidate, if they feel comfortable, talks about their faith…. it tells me more about the candidate.” That being the case, when Rick Perry suggested repentance might help America out of its economic predicament, while that might be a good theme for Jewish voters this time of year, my question to you would be, is that a sentiment that you think will resonate with the American people?

“I’m not sure how clearly this was conveyed in the National Review, but this is clearly a choice that each candidate has. If somebody decides that they want their religious beliefs to be private they have that right under our Constitution. But if somebody chooses to talk about their religious beliefs, obviously what they say may please some people and displease other people, so they proceed at their own risk.

“So going directly to your question, I suppose when a candidate talks about repentance as a way to hope for a better life, there are some people who will take that as so alien from their own experience that it will probably strike them as troublesome. Of course, I don’t, because those things which you talked about, teshuvah, repentance, have very powerful presence in the Jewish religious narrative and historical narrative. I’m not saying I’m for or against Governor Perry, but as I say, you proceed at your own risk if you’re talking about your religious beliefs.”

A Day of Rest

When Senator Lieberman is home for Shabbos, which is the majority of the time, he can either be found in attendance at Kesher Israel – The Georgetown Synagogue when spending Shabbos in the nation’s capital, or at Agudath Sholom in Stamford, when at home with his constituents.

Senator Lieberman grew up in Stamford, and then lived in the Westville neighborhood of New Haven for almost 25 years before moving back. In his book, he freely shares fond — as well as bittersweet — memories of his family.

Joe’s parents lived on the second floor of his maternal grandmother’s home until he was eight. Baba, as he called his grandmother, was strictly shomer Shabbos. The childhood memories of her Shabbos preparations, including the sweet smells of rugelach, challah, and kugel baking in the oven and the aroma of chicken soup wafting from the stovetop made lasting impressions.

His grandfather, Baba’s husband, had been religiously observant in Europe, but like many new immigrants to America, he went to work on Shabbos. Then in 1922, in a year when Shabbos would run into Shavuos, he decided to make amends.

“I will never break Shabbos again,” he told Baba and Joe Lieberman’s mother, who was then seven years old.

Little did he know how prophetic those words would be.

He went to shul that Shabbos morning. At the Shabbos meal, he complained of a pain in his arm. He agreed to walk over to see the family doctor, but only after going to Minchah. Baba walked him back to shul for Minchah, and as he left the shul for the doctor’s office, he crossed the street, was struck by a bicycle and thrown onto some trolley tracks, badly injuring his head. He died that day, perhaps from his injury, or perhaps from a heart attack, but he left this world as a Shabbos-observant Jew once again.

Senator Lieberman’s father, while not strictly Orthodox, began to learn and observe more as he got older, while his mother was brought up in a strictly Orthodox home. Young Joseph Lieberman became observant in his high school years, inspired partly by Rabbi Shlomo Carlebach z”l, whose nigunnim he danced to at one of the weeklong Torah Leadership Seminars sponsored by Yeshiva University in the 1950s.

He began to drift away following his enrollment in Yale undergraduate school in the face of the rigors of academia. It was only when his precious Baba passed away in 1967 that he returned to the fold, realizing that she was not only the link to his past but the key to ensuring a Jewish future for him and his family.

Senator Lieberman is also forthcoming in sharing his misgivings, including the time that his rabbi caught him at “Kiddush club” on Shabbos morning (he says it was his first, last, and only time he ever did it); the two occasions he got into a car to ride to the Capitol, or the handful of occasions on which he had to decide whether or not to pick up his phone that rang on Shabbos after hearing the caller identify himself on his answering machine. As chairman of the Senate Homeland Security Committee and chairman of the Airland Subcommittee of the Armed Services Committee (which has primary jurisdiction over tactical aviation programs of the US armed forces), pikuach nefesh issues can and do arise. Senator Lieberman says he has consulted with his rabbis to arrive at general guidelines in order to make informed decisions.

It almost seems as if you were baring your soul in the pages. How did you feel so comfortable about being so open about yourself and your family?

“Well, it’s good of you to say. I’ve never hesitated to answer questions about my religious beliefs and I’ve never hidden them. A couple of weeks ago I attended a program at Yeshiva University with Rabbi Meir Soloveitchik, and just by reference, he made an observation that I thought was really quite interesting, comparing me, l’havdil, to President Kennedy.

“He got elected at least,” quipped Senator Lieberman.

“But Rabbi Soloveitchik said the difference was that, in some ways, Kennedy was trying to not quite explain away his Catholicism because he was religious, but he was constantly trying to reassure people about it. I seem to be not at all hesitant to talk about my religion. Perhaps it’s just the stage of life I’m at. I’m upward of middle-age and hopefully I’m coming to the end of my career in elective politics. So I’m probably looking back reflectively. It’s probably why I wrote the book. Thinking about all the things that I’ve been lucky enough to witness, to be part of, to do, and to accomplish. One of the things that I thought I really had to convey was to write about Shabbat. This book may be one of the most important things that I ever do and part of it therefore was for me to be comfortable and open about my family. Also I talk here in much more detail about some of my religious overview through the framework and the architecture of Shabbat. I appreciate that you noticed that. I guess it’s where I am and what I wanted to convey and there’s no question, I did feel a comfort about conveying it.”

Heaven at 30,000 Feet

Senator Lieberman and his wife Hadassah have four children and eleven grandchildren. Our conversation was the second call the senator had placed that day to Jerusalem. His first was to his daughter, who is spending a year in Israel with her husband, a medical student who took off a year for learning at Yeshiva University’s Gruss Kollel in Bayit Vegan.

While family takes priority in his life, perhaps one of the senator’s most remarkably close-knit political relationships, in a town known more for partisan bickering than bipartisan cooperation, is his connection with Arizona Senator John McCain. The two sponsored the bipartisan legislation that established the 9/11 Commission in 2002 that investigated the circumstances surrounding those deadly attacks and recommended a plan to improve national security.

Senator Lieberman is a Democrat who broke ranks with his party after losing the 2006 Democratic Connecticut senatorial primary. Lieberman won reelection as an independent and then endorsed McCain, a Republican, in McCain’s failed 2008 presidential bid against Barack Obama.

The McCain-Lieberman relationship first took root in the 1990s, when the two senators worked closely on issues related to Kosovo and the Balkans following the breakup of Yugoslavia. Senator Lieberman writes that on one of their flights to the Balkans, Sentaor McCain was sleeping across the aisle from him. At the dawn’s early light, Senator Lieberman put on his tallis and tefillin and started to daven.

“I noticed John open his eyes for a moment and look at me, then close them again. Then, doing a double take, his eyes opened wide.”

“Where am I? What’s going on?” McCain blurted out.

“Johnny,” I said, “I’m just saying my morning prayers,” writes Sen. Lieberman. “I explained briefly about the tefillin and prayer shawl and he responded: “Oh good, for a moment there Joey, I thought I’d died and gone to heaven.”

“I could not help but say. ‘That says a lot about what kind of person you are, my friend: you think when you get to heaven you’re going to see a lot of Jews praying.’$$separate quotes$$”

What sort of reaction have you received from your colleagues in Washington to your new book?

“A kind of curiosity, and congratulations for having done it. I know John McCain has read it and he liked it a lot and tweeted on it. The rest of them said they wanted to get hold of a copy and read it but it just came out in August when everybody was out of town. They’re just coming back now and, of course, everybody’s busy.”

Senators Lieberman and McCain often travel together to the annual Conference on Security Policy in Munich, Germany, held every year since 1962.

In February 2004, the two were greeted by massive anti-Iraq war demonstrations that protestors had called to coincide with the conference which also draws NATO defense ministers and foreign ministers of NATO countries.

Senator Lieberman’s American contingent arrived shortly before sunset Friday. A US military attaché was on hand to greet the senator.

“As you have seen, senator, the streets around the hotel are sealed off with riot control vehicles and police cars. A few hours ago, I was called to come out and meet someone. I went out, watched the police vehicles separate, and through them walked a young rabbi with a beard, a black suit, and black hat, carrying a large shopping bag. When we met, he said he had brought the bag for Senator Lieberman for the Sabbath, and here it is.”

As it turned out, Senator Lieberman’s mother, who was still alive then and living in Stamford, had told her local Chabad rabbi that her son was going to be in Munich for Shabbos and probably needed the provisions. The rabbi e-mailed his colleague in Munich and the rest is recorded for posterity in Senator Lieberman’s book.

Reaching Inward

When his duties of office call upon him to participate in verbal votes or crucial debates on the Senate floor on Shabbos, Senator Lieberman will walk the approximately four-mile distance from his Georgetown residence to the senate building. If the weather is inclement he will sometimes spend Shabbos in his office and make Kiddush there.

Normally, though, he gets the weekend off. Shabbos, as a day of rest, is the major theme that he weaves through the book. And although the Capitol Hill crowd is one that thrives on action 24/7, Senator Lieberman describes what a gift Shabbos is, and can be for those who cut back to 24/6, disconnecting from their computers and BlackBerrys to spend quiet, contemplative time with family and friends.

He concludes each chapter with a few, often nondenominational, tips on how a person can get started observing a day of rest.

Did you have any feeling as you were writing this book that it could perhaps be used as a kiruv, as an outreach tool?

“I did. And I hope it is. I had many different feelings about it but part of it was to, as the book’s title says, offer the gift. Although it begins with a commandment on Har Sinai from Hashem to Moshe, it’s really a gift that I have from my parents, who got it from everyone who preceded me. So I wanted to do that.

“But in some sense I was hoping that this would also help to broaden ties between Jews and other religions, particularly Christians, because of some of the common origins of Sabbath observance. But there is no question that I also hope it would be used by kiruv movements to bring people in. I received an e-mail from one of the Chabad shluchim in Connecticut who said he was buying copies and sending them out, and he was hearing from other shluchim around the world that they were doing the same. It made me feel very good, and it’s why I wanted very much to put the section in at the end about ‘simple beginnings.’ I don’t expect people to just read the book and say, ‘Wow! I’m going to do this next Saturday,’ or next Sunday if they’re a Christian. But I expect it to get people to hopefully go step by step, mitzvah by mitzvah, observance by observance. So yes, it would be one of the great thrills for me if it was used for purposes of outreach, of kiruv. I should say more literally based on the word purposes, inreach, bringing in, as opposed to outreach.”

Senator Lieberman, how did the book help you with your own personal Shabbos observance?

“In doing this, I did find things that I had been, you might say, taking for granted. I wasn’t seeing [Shabbat] through the perspective of a visitor to Shabbat. What’s one example that jumps to my mind? The service of taking the Torah from the aron. It’s a grand service. So while I was writing the book I looked at it through the eyes of an observer who had not ever been to a shul before and it helped me to appreciate it more.

“I think there’s also the appreciation for the significance of the brachah we give to our children on Friday night. It is a very powerful moment, and I find people wanting to talk to me about that. So I think that gave me an even greater appreciation of it. We’ve had millennia now to build up halachot but also minhagim that are associated with Shabbat, and it makes it an extraordinarily rich experience. As I say, a lot of it I just feel because I’ve been doing it for a long time. But writing the book made me look at it from the eyes of an observer and made me appreciate Shabbos more.”

(Originally featured in Mishpacha Issue 379)

Oops! We could not locate your form.