On a Silver Platter

When Yitzchak Chaskelson creates a Kiddush cup, he knows he’ll never be able to replicate it. That’s because each of his silver items is handmade, chiseled and embossed from scratch, sometimes taking months, or even years, to complete.

Photos Ezra Landau

When he was little, Pesach was his favorite holiday. Little Itche would help clean and shop, and after all the hard work there was nothing more magical than watching his parents take down the Pesach dishes. Sitting at the Seder next to his grandfather, he’d listen enraptured as the elderly Holocaust survivor shared stories of Pesach in the town of Gura Kalwaria (Ger). There were sweet echoes of the songs sung in the legendary capella of the Imrei Emes, and moving tales of miracles in the Nazi death camps.

The year Itche Chaskelson was ten, Pesach became the date marking a personal geulah as well. He had just gotten over a bout of meningitis, and when he was finally released from the hospital, he discovered that he couldn’t fully control the muscles in his right hand. For Itche, this was devastating — for although he was just a little boy, he’d already shown a marked talent for drawing.

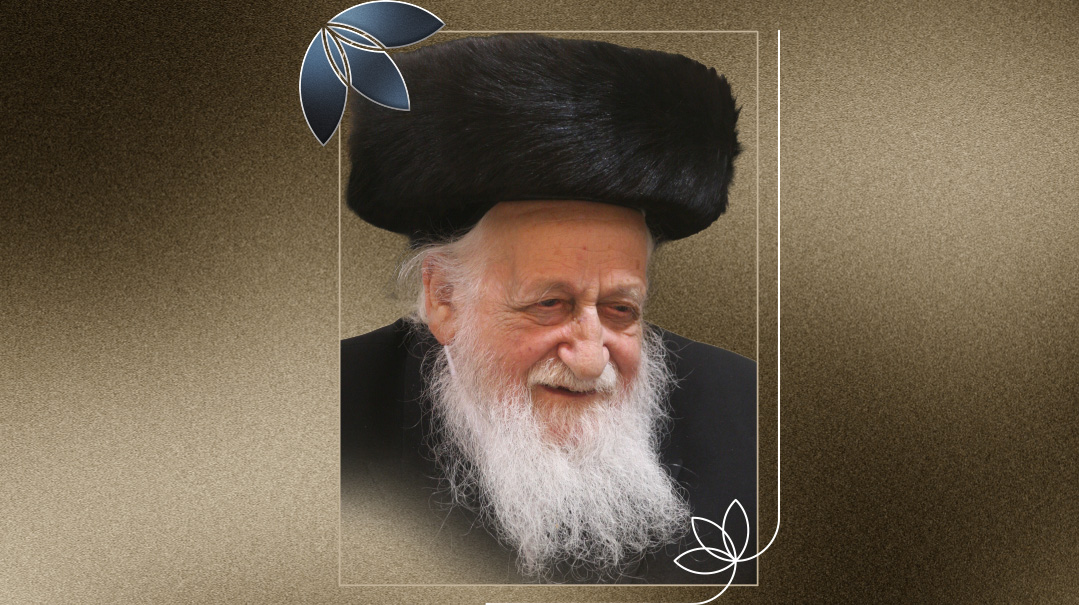

Seeing how miserable he was, a few days before Pesach his father took him to the Lev Simchah of Ger, hoping that the Rebbe could offer some encouragement to the poor child.

“Don’t worry, it’s nothing. Nothing. It will pass,” the Rebbe said as he held the anxious boy’s hand and looked compassionately into his eyes. True to the Rebbe’s word — in contravention to medical assumptions — Itche was back to his drawing pad right after Pesach.

As he expertly engraves a silver leaf, Yitzchak Chaskelson says he owes his unusual profession to that long-ago brachah.

Even I Can’t Copy It

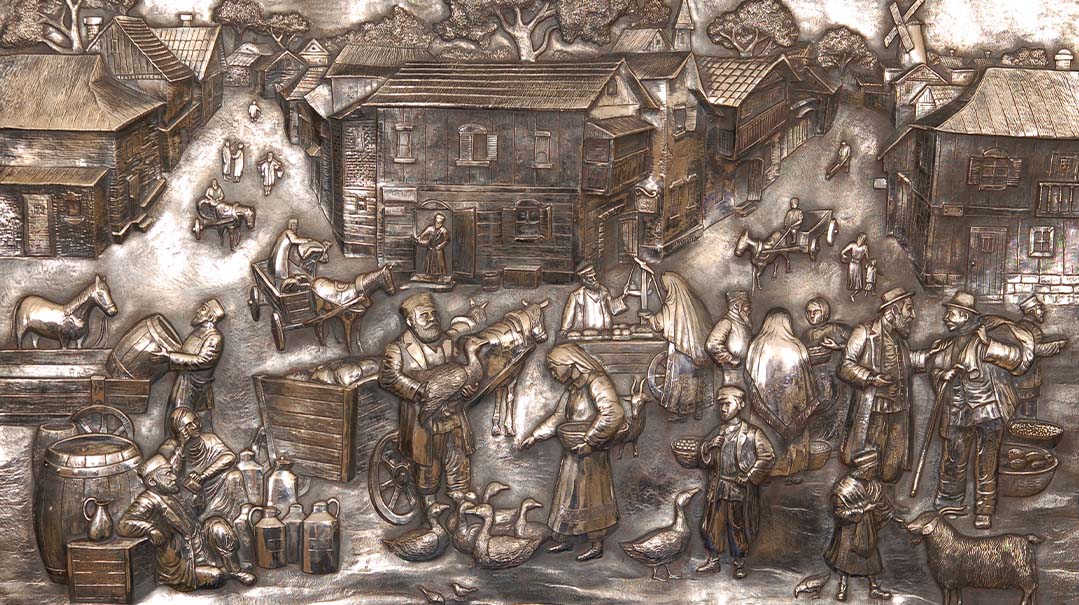

Yitzchak Chaskelson’s silver creations are breathtaking in their artistry and detail. They are also unique. From his nondescript workshop in Ashdod, 46-year-old Chaskelson lets his imagination soar back to the days of the shtetl, while his skilled hands recreate those picturesque scenes in silver relief on a becher, a wall mounting, or a Seder plate.

I’m holding a Kiddush cup embossed with a highly-detailed chuppah scene — I’ve never seen such an intricate design in my life. How much would such a thing cost, and which store carries it? The answer to the first question is a smile, and the answer to the second is “none.”

“It was ordered special for a wedding, and it took me three months to create,” says Reb Yitzchak. “There’s no other becher like this in the world, and because I create every piece individually by hand, I can’t create an exact replication, either.”

A “Real” Profession

Chaskelson was born in Monsey to a family of Gerrer chassidim. When he was a child, the family moved to Jerusalem. They returned to the US when Yitzchak was a teenager in yeshivah ketanah, but he opted to remain in Eretz Yisrael. He attended yeshivah gedolah in Haifa, and after his marriage, decided he wanted to learn art professionally.

“I had already dabbled in copper, and gained a bit of a name creating items from copper plates, which I would give to my friends or donate to shuls,” he says. “But I had this urge to gain real mastery and study the art of silversmithing on a professional level.”

Yitzchak’s father, however, told him to go find a “real” profession. He doubted his son would ever make a solid living as an artist. Loyal chassidim that they were, the pair agreed to ask the Pnei Menachem of Ger to arbitrate.

“The parshah that week was Vayakhel, and the Rebbe liked the idea of my working with silver. He gave me a brachah and cited the pasuk ‘Vayasu kol chacham lev.’ Then he wished me success. My father had no choice after that.”

Chaskelson went to study under an old artisan named Avraham Tabouri, a master silversmith who taught him how to create finely detailed embossed images in all different sorts of metal. “There aren’t too many people in Israel who do this,” Chaskelson explains. “It’s hard work that draws on multiple talents. Drawing, fine motor coordination, hand-tooling and engraving — and most of all, lots of patience. If you have it, you can get started, but it takes a lot staying power and persistence to create the types of pieces you see here.”

Pain of Separation

Some of Chaskelson’s pieces are products of his own inspiration. Others are specially ordered or commissioned. Either way, he can spend months on a single piece.

“I start with a drawing,” he explains, “and then I transfer it to the silver using a technique involving hot tar. Then the painstaking chisel work begins. On a typical day, I can sit here working for eleven hours straight.”

Chaskelson’s collection includes Kiddush cups, silver plates, and mezuzos, but he’s also made a miniature aron kodesh for the world’s smallest sefer Torah, and a small silver succah that was really a receptacle for an original manuscript from Rebbe Meir of Premishlan that someone wanted to put it in his succah. Virtually all his pieces feature the same motif: scenes of the shtetl — inspired, perhaps, by his grandfather’s vivid accounts.

“While learning in yeshivah in Haifa I spent a lot of time at my grandfather’s house,” he says. “He talked a lot about the days before the war, and those conversations generated a certain image in my mind.” Other images are based on the drawings that appear in the Sippurei Tzaddikim books. All have a quaint, innocent feel.

“My drawings are actually very simple,” he says. “But I think that’s the secret to creating authentic Judaica. Some people have advised me to study professional illustration techniques, but I have a feeling they’ll sabotage my signature style. There’s a certain Yiddishe authenticity in these creations, and I think my customers prefer it that way.”

The question of creating figures and embossments has been discussed in halachic literature throughout history, and worried Chaskelson for a long time before he came up with a solution: None of his images are complete. “I leave an ear out, or don’t complete the nose. I prefer to draw the people in profile, so that the face is always missing a part.”

Chaskelson’s creations are sold around the world for thousands of dollars, and today most of his creations are by order. He doesn’t advertise and most people who purchase standard silver items have probably never heard of him, but in the upscale market, people network and his name has earned a place of honor.

It also means he’s constantly parting with items he’s put his heart and soul into.

“Someone asked me to create a unique becher — a piece that no one else in the world would own. I made him a special becher for Purim depicting a shtetl scene the way I envision it, with people giving mishloach manos and dancing in the street. But it’s a piece I know I will never make again.”

If he could, he says, he wouldn’t sell any of his pieces. “I feel connected to each piece — I’ve worked on it for weeks and months. Whenever I part with something it’s heartbreaking, but it’s also my parnassah, so what can I do? At least I know these pieces are gracing people’s homes during the most important events of their lives. That gives me satisfaction.”

Market Shares

Chaskelson refuses to divulge any details about the most expensive piece he ever sold, but does talk about one that took him five years to make. “It was a silver engraving depicting a marketplace, with peddlers, horses, chickens, homes, trees, and wine barrels. It’s a huge picture, 80 by 50 centimeters (approximately 30 by 20 inches), and because of its size and scale, I refused to sell it for years — until I received an offer I couldn’t refuse.”

Chaskelson admits that there’s a very small market for his work, but he’s seen the demand develop with time. “It’s art, and anyone involved in art knows that there is a very small genre of people who understand it and purchase it. The market is small, but quality gets noticed and rewarded.”

Promoting his own work, Chaskelson acknowledges, is not his strength. He’s more interested in the quality than the profit. “Once I took an order for a custom piece and quoted a certain price, let’s say five thousand dollars, based on an estimate that the project would take two to three months. In the end, it took half a year. To be honest, I could have given my client the piece after three months — he would have been happy — but I knew that it wouldn’t be perfect, and I wouldn’t be happy. I had to take the extra time to make it the best I could, even if I would end up losing money. I guess I’m not the best businessman, but these types of things just can’t be pinned down to money alone.”

Because business is not his thing, his younger brother manages his overseas sales. “When I started out, I used to go meet clients and try to sell my work, but I was terrible at it,” Chaskelson continues. “I once went to this big gvir in New York and showed him my work. He wasn’t too excited and asked me how much my cheapest item was. I told him six hundred dollars, and he took six hundred dollars out of his pocket and said, ‘Okay, I’ll buy it. Take the money, at least you’ll leave my house with something.’ I thanked him but told him no thanks, I wouldn’t be selling him my work. He was taken aback, but I explained that I don’t want someone to buy my art just to do a chesed for me. I want someone who pays for it to appreciate it and really want to own it.”

The Most Beautiful Table

For years, Chaskelson dreamed of creating a one-of-a-kind Seder ke’arah. He spent the last three years actualizing that dream, and now the unique ke’arah has finally been completed. Its three shelves for matzos are adorned with magnificent images etched in silver.

“The ke’arah has six sides, with a different picture on each side,” he explains. “On one side is the text of Vehi Sheamda, set among fierce lions and fragile birds. On another side is the picture of a Jewish family seated around the Seder table. Another side is decorated with an image of bedikas chometz and another of matzah baking. There’s also the text of Chasal Siddur Pesach, and a picture of Rabi Akiva and his colleagues telling the story of Yetzias Mitzrayim all night long.”

The ke’arah, his most prized creation to date, has been sold for a record sum in the hundreds of thousands of dollars. Self-effacing and publicity-shy, Yitzchak Chaskelson says he probably wouldn’t have agreed to our interview before, but now that his dream Seder plate has come to fruition, he feels he’s reached a sort of turning point in his life where he can share his precious cache with the public.

“One thing is for sure,” he says, in a rare burst of confidence. “The person who purchased my ke’arah will have a unique Seder this year. With that kind of ke’arah on your table, you can’t help but appreciate the deeper beauty of what Pesach is all about.”

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 607)

Oops! We could not locate your form.