Of Miracles, Coal, and Kindness

| March 28, 2023The Herszaft family’s miraculous survival

As told to Riki Goldstein by Mrs. Esther Katz

I

was just six in May 1940 when we heard that Belgium had been invaded and the Germans were coming. We lived in Antwerp, where I was born and still live today, in a kleineh apartmentche on Wipstraat, one block away from the famous Kleinblatt bakery. My father sent me to check if Yesodei Hatorah, my school, was open. It wasn’t. He realized war had reached Belgium and that we needed to flee.

Relatives of my mother were in the coal business, and we piled onto their coal truck to get away. Actually, a lot of people were willing to pay to get a ride to safety on that truck, but my mother’s relatives said we would be among the lucky ones, even though we couldn’t pay. I think this was because of all the kindness my parents had done for the Jewish refugees from Poland and Czechoslovakia fleeing Hitler, who had streamed into Belgium during the years before the war reached us.

These people had nowhere to be, and my parents took them in. As long as there was sleeping space — even on the floor —people were welcome, and whatever money my father made from his work as a photographer went to buy food for all these guests. My parents’ rule always was, “If we have food today, we share it today, without thinking about tomorrow.”

Sometimes there wasn’t enough money for food. If my mother didn’t have any fish to cook for Shabbos, she would put up a pot with just water and onions, so her mother-in-law wouldn’t realize there was no fish.

My mother was a special woman, self-made. She had come to Belgium from Czechoslovakia in the 1920s as a single girl, with the brachah of the Ahavas Yisrael of Vizhnitz. Orphaned of both parents by age nine, she asked the Rebbe if she could travel alone to Antwerp and work as a seamstress so she could send money back to her younger siblings. Her work would supply her sisters with a dowry, without which they would not be able to marry.

The Ahavas Yisrael gave Mama his blessing. She worked hard in Antwerp and sent the money back to her shtetl, enabling her sisters to marry. Our good-hearted Papa, meanwhile, decided she was the one for him, and married her with no dowry at all. In fact, he even paid for her wedding dress.

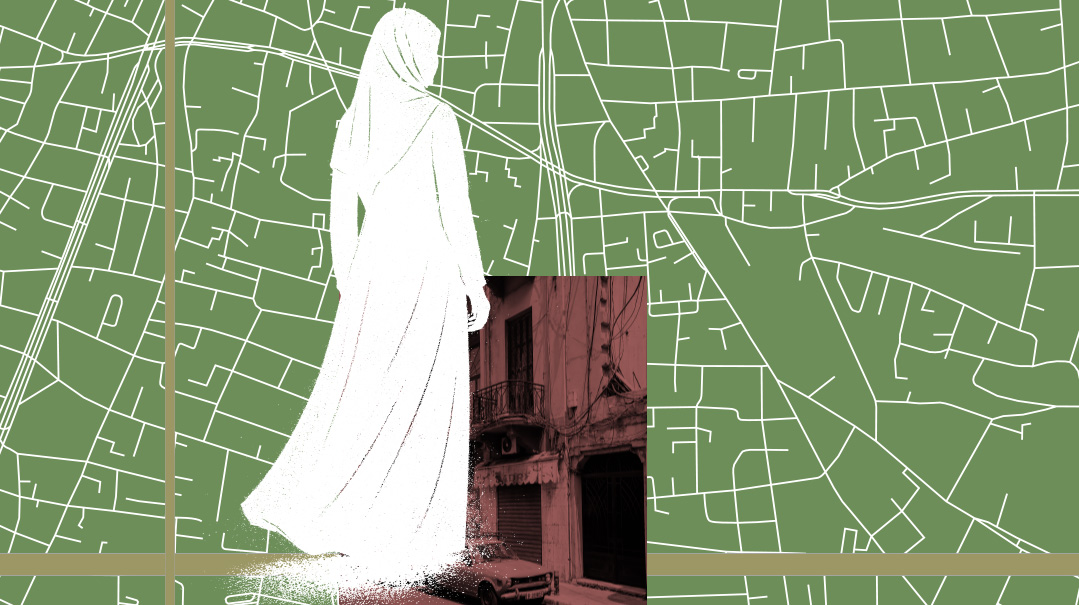

In May 1940, when it was time to run from Antwerp, my mother was expecting, in her seventh month. My older brother Shloime was seven, I was six, Leizer four, and Chaim just one year old. We were a bunch of little pitzkelach holding on to Mama’s skirts. So people felt sorry for her and said, “Let her go, let Sureh and the children go.” We took what we could along with us, a docheneh [quilt], and pillows, and so on, but not much, because war came to Belgium on Friday, and by Monday, we were on the road. You know the pictures you see in the papers today of refugees who ran from the war in Ukraine? That was what we looked like: refugees with bundles and blankets.

Oops! We could not locate your form.