Nursing Wounds

| January 20, 2026A massive nurse walkout leaves hospitals and patients scrambling for solutions

Photos: Shutterstock

As 15,000 nurses from Mount Sinai, Columbia Presbyterian and Montefiore hospitals in New York City continue their strike, patients and chesed organizations are scrambling to manage the fallout

Rabbi G. was scheduled to have spinal surgery at Columbia-Presbyterian Hospital to address a condition his doctors feared could lead to serious risks if left untreated. His children arranged to take turns being at his side and for one of them to spend Shabbos nearby in Washington Heights.

Then everything changed.

“I remember hearing something about a nurses’ strike in New York and thinking, ‘What does that have to do with me?’ ” said Yaakov*, Rabbi G’s son. “The next day, my brother called me to say my father’s surgery was being moved to another hospital we’d never heard of.”

Comparatively, Rabbi G.’s situation was better than many in similar positions. The walkout by 15,000 nurses led to countless canceled surgeries, causing backlogs likely to last for months.

At press time, the strike looked likely to head into its second week, with both sides digging in. It’s already the longest nurses strike in recent memory, eclipsing the three-day walkout in 2023. Although that dispute led to more favorable contracts for nurses, their hopes this time around for staffing and pay increases, as well as protections for health benefits, have been frustrated by hospital management, which seems determined to hold its ground.

Rabbi G.’s doctor, through his senior position, was able to move the operations he felt were most vital to an affiliate, Presbyterian Hospital Westchester in Bronxville, New York.

“We’re lucky that it’s not so far away and the doctor is bringing his team with him,” said Yaakov. “But overnight, everything became a question, from who’s going to be the support staff to how Shabbos is going to work in a place with no nearby place to stay and no bikur cholim room.”

Many perusing the news might have heard about a nurses’ union strike at three major New York hospitals and moved on to stories about Iran and Greenland. Yet for those in need of acute medical care and the dedicated corps of chesed organizations that assist them, navigating the fallout added hurdles and unknowns to already challenging situations.

Mount Sinai, Columbia-Presbyterian, and Montefiore hospitals play a big role in providing the expertise that brings thousands to New York City for treatment. When their nurses walked out, the rug beneath these vaunted institutions got pulled out, leaving hospital directors and patients scrambling for effective solutions.

Plugging Holes

Over the years, the New York State Nurses Association (NYSNA), which represents a large chunk of the city’s nurses, have had their share of contract disputes with hospital management, often going down to the wire. But as months and weeks ticked down to the January 12 contract deadline, with both sides at loggerheads, hospitals got word to prepare for what could be an extended strike.

Stopgap options for the hospitals are limited. The main response was hiring thousands of temporary nurses, some from local agencies, and many more from traveling teams. Still, relying on short-term plugs, with new staff unfamiliar with the turf and limited in numbers and expertise, is challenging.

“I got an SOS message looking for a nurse who knows how to care for a very specific type of dialysis for twins in Columbia,” said one nurse who works in a hospital in a New York suburb and asked not to be identified.

Those gaps left hospitals grasping for plans.

“We started having various calls and Zooms with CEOs, medical directors, and doctors to figure out what this would mean on the ground, but they were clearly hedging, without concrete answers,” said Reb Boruch Ber Bender, president and CEO of the Five Towns–based Achiezer Community Resource Center. “There was just so much that was unknown, and that alarming feeling trickled down to patients and families. Once we saw that lack of clarity and confidence, we shifted to reaching out to other hospital leaders, doctors and every part of our Rolodex to help give the families we’re involved with the best possible options we could.”

Hard Choices

As hospital units downsized and staff warned families that they would likely have to transfer out, finding new places to get care became a major source of stress.

“Imagine the panic parents feel when they are told their extremely premature babies will need to be transferred elsewhere,” said Chanie Feigenbaum, a pediatric hospital liaison who works closely with families and is in regular contact with community based medical askanim.

Columbia became a centerpiece of the challenge for chesed organizations. The hospital typically attracts many Orthodox patients, most domestic, but a steady amount travel from Eretz Yisrael to receive treatment as well. The hospital’s newborn and pediatrics departments regularly treat 60 to 70 frum children. As the strike approached, doctors warned that most would have to leave.

“The week prior to the strike, when most of the transfers happened, was tense,” said Shoshana Polakoff, a Chesed 24/7 liaison to Columbia. “Even when everyone was doing their best to be professional, you could feel emotions were high. Baruch Hashem, Chesed 24/7 is a network so, with patients’ permission, we can keep in touch with other hospitals, liaison to liaison, and maintain a continuity of care.”

More than half of the babies and children there were transferred to other hospitals. Columbia’s pediatric cardiac department closed entirely.

A medical coordinator for Chaim Medical Recourse who asked to be identified only as Moshe said some transfer decisions were straightforward.

“Most of the babies they transferred out were not in bad shape,” he said. “They were preemies with feeding issues and things like that, which really didn’t need the level of care this NICU gives.”

Left behind were cases too delicate to move, and nearly no new admittances were accepted.

“If you’re expecting and know the baby may have a serious health concern, you were likely planning to deliver at Columbia, where the care team had been closely following the pregnancy and preparing for specialized care after birth,” said Mrs. Feigenbaum. “But suddenly, we were asking ourselves where they would go instead.”

Transfers and diversions left some families with difficult choices. The easiest logistical options were to send patients to other New York area hospitals, but for some with rare and highly acute conditions, the best suited hospitals might be very far from home.

“It’s great to find out that a top hospital in Boston, Philadelphia, or Texas will take you, but if you have six kids at home or you aren’t sure if Medicaid will cover treatment there, then not all options are truly on the table,” said Rabbi Bender. “In a situation like this, some people sadly couldn’t choose the options with the best possible care.”

Loggerheads

The confrontation between three major hospitals and their nurses’ union loomed in the background of everything that patients and their families were dealing with. Both figuratively and literally: They had to pass through picket lines to get into medical buildings, and they could hear strikers’ speeches and chants while inside.

Both sides threw harsh rhetoric. A statement from Columbia-Presbyterian cast the strike as “NYSNA [telling] nurses to walk away from the bedside” and called their demands “unrealistic.” NYSNA says the three hospitals are waging “a war against union nurses” while flush with money.

The union’s key demands are wage and health coverage adjustments they say are needed to cover increased costs of living. They also want commitments to more staffing and better protection against workplace violence.

“We would not have walked off for salary alone,” said Shevy Rosner, a striking nurse who works at Columbia’s NICU. “We need safe ratios to be able to take care of our patients. Right now, the hospital has no accountability.”

Mrs. Rosner said that the hospitals were refusing to negotiate fairly.

“They laughed and walked out,” she said. “These CEOs make millions. They make tremendous profits and have money to build all kinds of new fancy centers to attract patients.”

Mrs. Rosner also pushed back emotionally against portraying striking nurses as shirking their responsibilities. “Nurses want to be inside. We cried on our way out, and the minute we have a contract we’ll be back to caring for our patients.”

Nursing strikes do occur, but 15,000 walkouts is a record for New York.

Nurses also received unqualified support from Mayor Zohran Mamdani and state attorney general Letitia James joining the picket line. Mr. Mamdani put blame squarely at the feet of hospitals, saying, “There is no shortage of wealth in the health care industry.”

Past elected officials took more neutral positions, urging both sides to compromise.

High health care costs, coupled with generous executive salaries and state-of-the-art pavilions, make hospitals an easy target for populist anger, but leaders say they cannot afford to give nurses the 25% salary increases they demand.

Charie Chan, an expert in health care systems who teaches at Columbia Business School, says many hospitals operate at a deficit.

“Hospitals generally want nursing staff to be happy and healthy,” she said. “They would love to meet some of these demands, but they’re in a very strained situation. We have an aging population, which means more prevalence of chronic diseases, so they’re dealing with more people who come to the hospital in a sicker state. That takes more resources.”

Another challenge of the aging population, Professor Chan said, is that lower reimbursement from Medicare and other government payment plans leave hospitals losing an average of 20 cents to the dollar on such patients.

“These losses have been supplemented by private pay patients, but as the population ages and more people are on Medicare, that balance is shifting,” she said.

Professor Chan also said that new buildings and centers create a mirage of hospital wealth. “A lot of that is paid for by philanthropy and grants for new research,” she pointed out. “The funds are earmarked for things that can have a name put on them.”

New Reality

As the strike set in, patients and their families settled into a new reality. Some units were little altered, but in many others, that was not the case.

All surgeries deemed elective were canceled, and in many instances, tests were put off, sometimes calling advocates into action.

“A patient needed a biopsy, but the hospital didn’t think it was enough of an emergency and canceled,” said Chana Landau, founder and director of Refuah Helpline. “We did think they needed it now and had to push to get it done.”

In some instances, liaisons found themselves at odds with doctors over whether patients were stable enough to be moved or whether they could receive suitable care in other locations.

“We have few patients left at Columbia, but for some of them, navigating the situation required significant coordination to ensure they could remain here,” said Mrs. Feigenbaum.

The hollowed-out pediatrics units left a markedly different environment.

“It seems very calm and quiet,” said Mrs. Polakoff of Chesed 24/7. “But you don’t have the camaraderie of the nurses, the talking among themselves as much, and it affects the whole mood. The atmosphere is more intense. We’re getting all kinds of reactions from patients. They’re getting the medical care they need, there are more doctors on the floors, and the support staff is available, but there is an uneasy feeling.”

That anxiousness has left its mark.

“The traveling nurses might be great, but they don’t know my kid, and a lot of cases have so many delicate nuances,” said Rabbi Bender. “One person told me that he and his wife haven’t left their child’s bedside for one moment since this happened. That’s an unbelievable amount of further strain to deal with.”

Those in the trenches shared similar experiences.

“We had a crisis at Mount Sinai and wanted to make sure everything went smoothly as new staff came on, so our liaison was there at 2:30 a.m.,” said Mrs. Landau. “We’re all working overtime.”

Substitutes

Down-sized operations did bring some advantages.

“The patients that haven’t been sent out of the PICU and NICU are very happy with the traveling nurses, and now they have the same number of doctors with less patIents,” said Chaim Medical Resource’s Moshe.

Reviews of traveling nurses covered a wide range, especially as some were first navigating new turf with at times raucous demonstrations in the background.

“When they first came, it was a challenging transition,” said Mrs. Feigenbaum. “Imagine bringing in new nursing staff and learning unfamiliar systems while trying to locate basic supplies like infant formula.”

Importing an army of nurses is no simple task. These temps, who travel from around the country, get paid far more than salaried employees, as well as receiving room, board, and transportation. Costs to hospitals are enormous, a factor adding pressure for them to reach a settlement with their regular staff’s union.

Hospitals assemble barriers to protect their privacy from the striking nurses they pass on the way in to work.

In several instances, replacement nurses struggled over the first days of the strike to find their way around these huge hospitals.

“These nurses come from all over the county, and an ICU in Oklahoma looks very different from one here,” said Mrs. Rosner, the Columbia NICU nurse. “We get the sickest of the sick. These nurses are trained, but obviously don’t have the same qualifications as us.”

On the Move

The patients transferred or diverted to other hospitals had the advantage of working with regular staff nurses, but many faced some challenges in acquainting a fresh team with the contours of their case.

The strike comes at a difficult time for hospitals, which are already dealing with high patient censuses driven by flu season.

In advance of the strike, several area hospitals began to prepare for a heavier load. A mother-baby nurse who works at a suburban New York hospital said they were expecting at least 11 new babies in their NICU and that managers put out messages asking staff to pick up additional shifts.

The smoothest place for Columbia patients to land is Cornell Medical Center, which is also in Manhattan and operates under the same umbrella, allowing doctors to work in either facility.

“Cornell prepared for this for a while and brought in more doctors and nurses,” said Chaim Feldman, Refuah Helpline’s Cornell liaison. “They’re a little overwhelmed, but they don’t take more than they can manage.”

Moshe of Chaim Medical Resource said the patients he was in touch with were managing well. “Columbia’s pediatric surgeons are doing surgery in Cornell now, and a lot of the PICU patients were sent there too. They’re both officially level four care, but in reality, Columbia’s is better. Still, it’s not such a disaster, baruch Hashem.”

Some of the toughest transitions were felt by those who had to move far from home to get the care they needed. A child who had been at Columbia on a highly specialized device was only able to find comparable treatment in Cincinnati Children’s Hospital.

Sarah Greenfield is a main point of contact for Orthodox families traveling to Cincinnati to get treatment for their children. While transfers often come with resistance from hospitals and insurance companies, the background of strike cut through both.

“The doctors themselves became hysterical and initiated the transfer,” said Mrs. Greenfield. “That took care of the usual obstacles.”

The challenges of caring for a sick child far from home present no shortage of difficulty. Mrs. Greenfield and Cincinnati Bikur Cholim, led by Rabbi Yisroel and Yocheved Kaufman, try to take off some of that edge.

“When they came after a traumatic transfer, their apartment was ready with food in the warmer,” she said.

Some patients in Cincinnati stay in housing provided by the Ronald McDonald organization, others in the Yiddy Greenfield House, a nine-unit apartment building operated by the Greenfield family. Three kosher meals per day are provided for families by Cincinnati and Centerville Bikur Cholims.

“When you feel cared for and validated, it helps you focus on the goal you came here for,” said Mrs. Greenfield. “We try to think ahead and plan for the problems people might face. It makes it a little easier for them to manage.”

* Names have been changed.

On Guard Every Second

Sheva Epstein

Mimi Samuel’s four-month-old baby, Shlomo, has been in Mount Sinai’s NICU for some time now, and come January, her nerves were shot from the ups and downs of the past few weeks. On top of having a very sick baby battling organ failure and multiple infections, she and her husband were also anticipating the strike and working on a backup care plan for several weeks with the team at Mount Sinai.

“The COO was pulling families into the conference room the day before the strike, saying, ‘Things may look different,’ ” she says. “Our doctors were telling us that they have a good plan for us until Wednesday. Our regular nurses are great and experienced with the specialized treatments our son needs, but when the strike starts, they have to walk out.”

Mount Sinai was very much on top of things. A few weeks prior, they had told Mimi they planned to substitute their regular nurses with traveling nurses and arranged for extra teams of doctors and nurse managers on the floor at each shift. They also brought in some traveling nurses weeks in advance for training. Some, Mimi says, have been excellent; others were decidedly not.

“I overheard a travel nurse in the family lounge right before the strike saying, ‘They’re going to put me soon on the sicker side of the NICU and I am so not ready’ — not something a parent with a baby on the sicker side of the NICU wants to hear,” Mimi wryly remembers. “One family told me the first day their nurse didn’t show up until 10 a.m. — three hours late — and another family found half a glove in their baby’s diaper. We question where the other half is…”

One travel nurse was completely uninterested in being trained to administer Shlomo’s treatment.

“She was rolling her eyes and saying, ‘We don’t do this treatment’ — she was more out of the room than in,” Mimi reported to the head nurse. “I don’t want her near my baby.”

The hospital also told the Samuels they had arranged for a former NICU nurse to take over Shlomo’s care until her shift’s end on Wednesday, at which point they would have no one on hand to oversee Shlomo’s care. They coordinated transfer to a children’s hospital several states over with personnel specializing in Shlomo’s condition, so if by Wednesday night, Mount Sinai didn’t have another competent nursing professional in the ward and the strike wasn’t over, they would need to medevac Shlomo to the second hospital.

“So as of the Shabbos before the strike, basically I could tell you I’m here with him until Wednesday,” Mimi says. “After that, we didn’t know. My bag was packed and ready to go.”

And then on Sunday, the night before the scheduled strike, that former NICU nurse decided not to come back, and the hospital told Mimi they had someone who could be there until Tuesday, and beyond that they didn’t know.

But stressful as the unknown has been, Mimi is grateful.

“Columbia already shut down two entire floors last week,” she remembers hearing, sharing how the hospital transferred out patients that first week in January. “I don’t know where they sent them, but I’ve heard it’s a total mess.”

Come Monday morning, all the regular nurses had to put their things down and just walk out. Mimi made sure to be in the ward at Shlomo’s side at 5:30 a.m. The striking nurses left at 6 a.m., and the doctors and nurse managers manned the floor until the travelers showed up at 7.

“Since then, I’ve felt like I can’t let my guard down for even a second,” Mimi says.

Even the substitute nurses who were eager to perform Shlomo’s treatments and learn the technique were asking Mimi, “Do I do this next? How do I prep this part?” while running his machines. They were learning on the job what it meant when the machine sounded an alarm and to move quickly to fix the issue — but that lifesaving instinct was being developed only in the moment.

“And the whole time, we’ve been walking this very fine line of being fierce advocates for Shlomo, and at the same time trying to put on a smile, to make a kiddush Hashem, to be pleasant and grateful,” Mimi says.

There have been exceptional travel nurses, Mimi recalls, like the one who took no break the first day of the strike while taking care of Shlomo, and the specialty nurse who heard someone wasn’t coming for the night shift and stayed well past the end of his shift at 7 p.m., until 2 a.m., to follow Shlomo through to the end of his treatment.

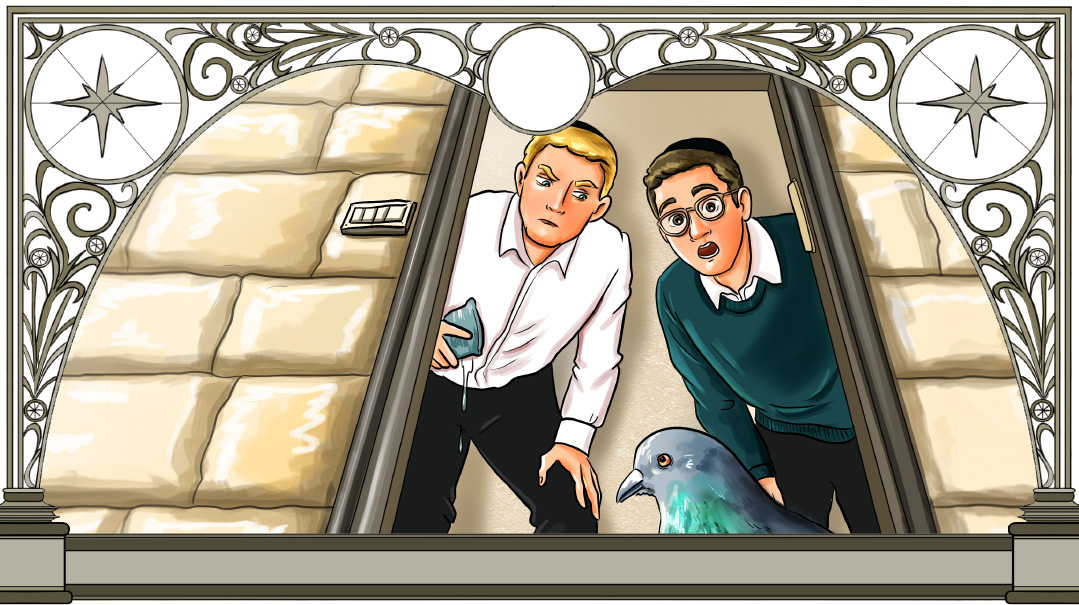

And since Monday, the group on strike outside the window has been growing.

“It was crazy,” Mimi says. “I looked out and saw more and more nurses. Then came someone with one of those bullhorn-megaphone things, there was shouting and you could hear the noise from up here, and every time I looked out the group just got bigger and bigger. They’ve been picketing hard outside — it sounds like color war, especially midday.”

Throughout all of it, all Mimi could think about was that if Shlomo did need to be transferred, the repercussions would for her family would be long term.

“We knew if he were transferred, we’d need to stay there until he’s ready to come home,” Mimi says. “He’s a very sick baby, too sick to be moved back and forth even once the strike ends. And that means my husband will be in New York for his job and taking care of the rest of our family, while I’m in a different state with Shlomo for at least several months, if not longer. If it plays out like this, we won’t be together as a family for who knows how long.”

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 1096)

Oops! We could not locate your form.