Numbers Game

Why pollsters are split about Bibi's political fate

1

In October 2022, a week before the last elections, I visited Metzudat Zeev and saw Netanyahu pacing the Likud headquarters like a lion in his cage. With two cigar butts in the ashtray, Bibi consumed the polls brought to his desk like fresh-baked rolls.

Among Israeli politicians, Netanyahu is an unrivaled campaigner, bobbing and weaving with the latest poll numbers. He won his first improbable victory in 1996 after bringing on the famed American political advisor Arthur Finklestein, who commissioned the in-depth polls that first brought to light the dichotomy between Jews and Israelis. Netanyahu has exploited that divide ever since.

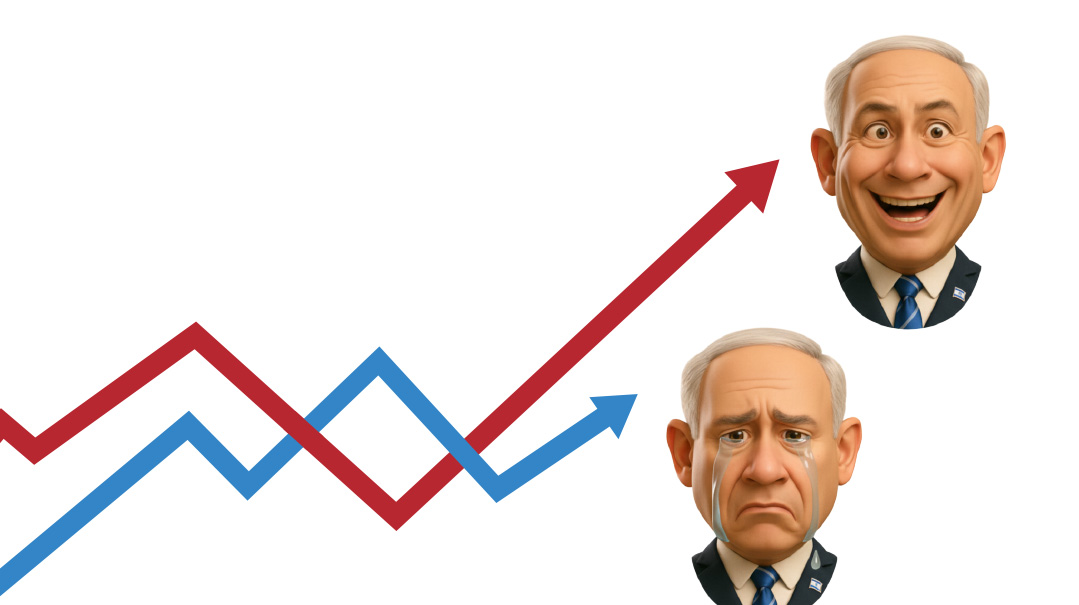

A week before the last elections, after a string of inconclusive votes that ultimately ushered in the “change government,” Netanyahu was especially nervous. “It’s the trend that matters,” he said, pinpointing the key datum — momentum. If the trend line favors you in the week before election day, chances are good that you’ll close the gap.

That said, the polling industry’s credibility has taken a hit in recent years. On the one hand, polls conducted for center-left news outlets have shown dramatic leads for the opposition bloc, with one last week putting the opposition at an incomprehensible 70 seats. On the other hand, polls commissioned by right-wing outlets — Channel 14, and recently i24 — show the right-wing bloc holding steady at around 60 seats.

To get a sense of what’s behind this divergence, I spoke to a number of polling experts. What I heard surprised me. Over the past two years, starting during the judicial reform crisis but intensifying after the outbreak of war, pollsters have identified a growing number of Israelis who don’t intend to vote in the next election. The different ways pollsters interpret this finding, either digging deeper or simply leaving them out, yield starkly different results.

2

The late Shimon Peres, who underperformed his polling in election after election, famously observed that polls are like perfume: They smell good, but they’re not for swallowing. This time, you can’t even enjoy the smell. Each pollster offers his own fragrance, and you can’t even waft in the sweet scent of a simulated victory.

One pollster I spoke with shed some light on the mystery. The Israeli political landscape in 2024–25 is built on a foundation of quicksand. Most of the disaffected voters come from the right. Many say, perhaps for the first time, that they’ll sit out the next election. What pollsters do with this datum swings the results dramatically one way or the other.

If you simply disregard respondents who say they won’t vote, you very quickly get to a dramatic political realignment and a sweeping opposition victory. But some pollsters break it down differently. With so many uncommitted voters, you have to ask follow-up questions: Whom have you voted for in the past? How confident are you that you won’t vote? Have you hesitated about voting in the past?

When you dig deeper, you find that many disaffected right-wingers will ultimately drag their feet to the polls and vote for a right-wing party. Contrary to the public perception that right-wing voters “swarm to the polls” — to paraphrase Netanyahu’s infamous warning about Arab voters in 2015 — it’s actually in heavily left-leaning cities where turnout is the highest.

The only exceptions are settlements and chareidi cities, whose turnout rates match urban strongholds, offsetting the left’s advantage. And most pollsters model chareidi voters statistically rather than polling a representative sample, which further distorts polling results, often in the left’s favor.

Bottom line, it’s mass that will determine the winner on election day. The better the right does at waking up its voters and turning them out, the better the bloc’s chances of closing the gap.

For decades, the Israeli right has outperformed the polls in almost every election. That occurs not just because of pollsters’ political leanings, but because the right is less politically engaged, voting less and hesitating more.

3

Just over a year ago, Benny Gantz led the center-left bloc with over 40 seats in the polls, looking like a shoo-in for prime minister. But in recent polls, Gantz is hovering around the electoral threshold (3.25 percent of the vote, or four seats), resorting to gimmicky speeches about potentially rejoining the government just to stay relevant.

Unlike the right, which remains loyal to its leaders over long periods of time, from Begin to Netanyahu, the Israeli left changes its leaders like socks — and not like the soldiers in Gaza, who only change socks every few days. Analyzing elections results and polling graphs, one is struck by the center left’s fickleness. From Tzipi Livni and Yitzchak Herzog to Yair Lapid and Benny Gantz, left-wing voters have flocked to leaders best positioned to oust Netanyahu.

Early in the current term, that was Benny Gantz, who after October 7 looked like a sure bet to replace Netanyahu. With Gantz fading as quickly as he rose, Naftali Bennett has emerged as the latest savior, albeit with a caveat.

Apropos of voting patterns, Naftali Bennett’s polling numbers have consistently trended downward as election day approached. After reaching as high as 30 seats a few months ago, Bennett has already declined to the low to mid-20s, on a good day. Right-wing outlets are already placing him in the low teens, or even single digits.

This fluctuation points to the real story of the leaderless center-left bloc, which always goes for the shiny new object. The newcomer also benefits, and even a familiar figure like Bennett looks like a fresh face as he comes out of retirement.

No date has been set for the next election, and Netanyahu is trying to extend the coalition’s lifespan for as long as possible and bring its components together, including the chareidi parties, which at least to appearances are out of the game. So it’s way too early to predict whom the left will rally around in the next elections. It could be a new party led by ex-Mossad chief Yossi Cohen and former chief of staff Gadi Eizenkot. Or an alliance between Lieberman and Bennett.

“I don’t get involved in how the left divvies up its seats,” Netanyahu once said sarcastically. Everything is still possible, and even current front-runners know they don’t necessarily have an advantage.

Two people who know better are Binyamin Netanyahu, who almost always outperforms the polls, but knows from bitter experience that that isn’t always enough; and Naftali Bennett, who has consistently bagged about a third the number of seats he started out with. In one election, he even crashed below the four-seat threshold, despite polling at double digits at the start of the campaign.

For now, all we can do is take a good whiff. Whether you’re on the right or left, you’re sure to find at least one fragrance you like, and probably a few less to your taste.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 1078)

Oops! We could not locate your form.