Nothing’s Really Changed

Rav Ovadiah Yosef's sons relive the early years

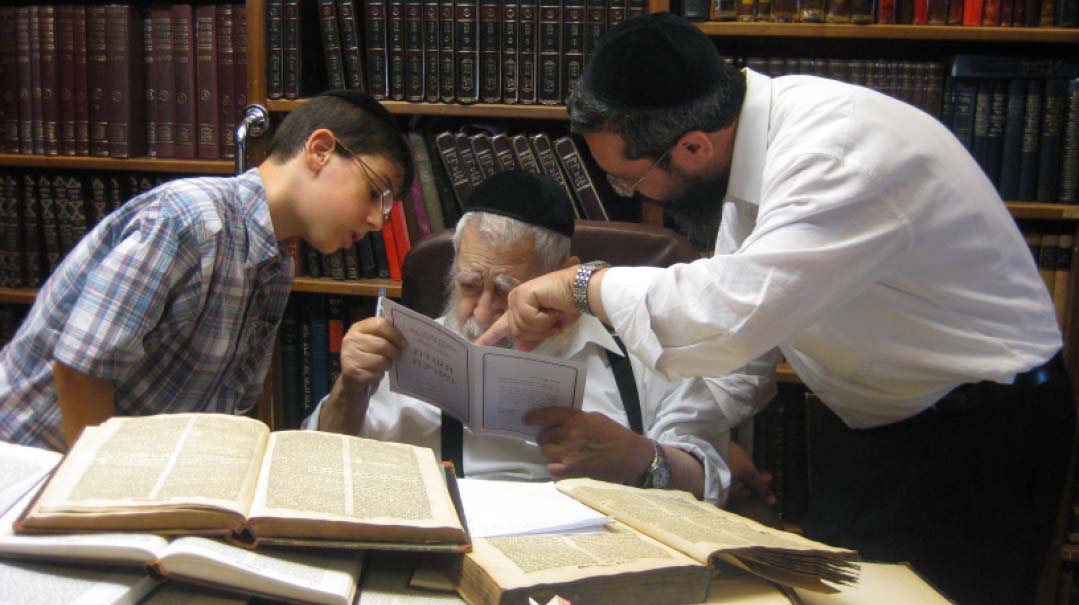

Photos: Elchanan Kotler, Yaakov Sinai archives

Eight years have gone by since the passing of Rav Ovadiah Yosef ztz”l on 3 Cheshvan, but walk into his room in the apartment on Rechov Hakablan in Har Nof, and it’s as if life is still pulsating there. Everything remains exactly as he left it, open to the public with a warning taped to the bookshelves: “Please do not touch the seforim.” The old table is protected by a sheet of glass, and in a sealed display case are the traditional robe, silver cane, and the turban that were his trademark.

But today’s visit is more than just a glimpse into the room of this gadol, former Israeli chief rabbi, and the venerated Sephardi posek of the generation. It’s also a meeting of Rav Ovadiah’s oldest and youngest sons, two busy rabbanim who’ve come together to share their illustrious father’s legacy. Rav Avraham Yosef is former chief rabbi of Holon and Rav Ovadiah’s fourth of eleven children (five boys and six girls) and the oldest living son since the passing of Rav Yaakov Yosef ztz”l in his father’s lifetime. He’s here together with his youngest sibling, Rav Moshe, who heads the Beit Yosef kashrus and Maor Yisrael, the publishing firm dedicated to publishing his father’s writings.

Seventeen years separates them and so do the experiences of elder and youngest child growing up in the famous household. They’re at opposite ends of the family and had very divergent experiences growing up, encountering their father in very different settings and in the perceptions of the public. But at the core, the passion and focus of the father they both knew were one and the same.

This spacious apartment, of course, wasn’t their childhood home (although Rav Moshe and his wife Yehudit moved in as Maran’s caregivers in the later years of his life). Yet some things remain sacred no matter where they are. Neither of them, of course, dares take his father’s chair. “We’ll never sit in his place,” Rav Avraham says. The bedrooms, the living room, everything here has been converted into a giant Torah center, with a shul and publishing house dedicated to editing Rav Ovadiah’s massive stashes of writings.

“This spacious apartment, the extensive library — all this belongs to the later period of Abba’s life,” Rav Avraham qualifies. “When I was born, when we were growing up, we lived in dire poverty.”

He remembers the day when, as chief rabbi, Rav Ovadiah was given a luxury car and driver — it was 1973, and a Ford Gran Torino was placed at his disposal. “When the car was delivered to us, I saw Rav Eliyahu Shrem, a rosh yeshivah and our neighborhood rav at the time, crying. I asked him why, and he answered, ‘I remember when your father first came to Porat Yosef in the Old City, where I was the librarian. He would walk there in his tattered shoes with worn-out soles, so that his socks were always soaked from the rain. He’d walk into the library, wring out his socks, look through seforim while waiting for them to dry out a bit, and only then he’d enter the beit medrash. So how can I not weep when I see fulfilled before my very eyes Chazal’s promise that anyone who fulfills the Torah in poverty will live to fulfill it in wealth?’”

A Few Lirot

Rav Avraham remembers those austere early days. “Abba used to read the Torah in three shuls every Shabbos, for a salary of a lira and half,” Rav Avraham, who was born in Egypt in 1949 when Rav Ovadiah was serving as head of the Cairo beis din, recounts. The family returned to Israel with four small children in 1950. “We were living in a tiny rented house in Beer Sheva. When my sister was born, her crib was a wooden crate for oranges, cushioned with some rags. The house consisted of one and a half, maybe two rooms. In the smaller room was a folding bed that was put away during the day so that Abba could learn there. Most of the week, the table was loaded with seforim. Only on Erev Shabbos, Abba would put the books back on the shelves so that Ima could prepare the Shabbos table.”

The Yosefs received a little help from Rabbanit Yosef’s father, Rav Avraham Fattal. “But,” says Rav Avraham, “Abba had no livelihood, and he considered returning to yeshivah, but there were already four children, Abba was 30, and the draft was nipping at his heels.” At this stage help came unexpectedly from the chief rabbi of Jerusalem, Rav Tzvi Pesach Frank ztz”l.

“Abba was held in high esteem by Rav Frank,” Rav Avraham relates. “When he heard that Abba was stuck without a job and was about to be drafted, he gave orders for him to be allowed into Midrash Bnei Zion, which he headed, and told the menahel Rav Yitzchak Rosenthal to pay him a monthly salary. In fact, it was there that Abba would become close to the Ashkenazi gedolim of the day — Rav Binyamin Ze’ev Prague, Rav Shmuel Rosovsky, Rav Bezalel Zolty, Rav Shlomo Zalman Auerbach, and Rav Yosef Shalom Elyashiv all learned there for a time, and that’s also where Abba picked up his Ashkenazi pronunciation.

“Rav Frank’s respect for Abba’s Torah was immense,” Rav Avraham continues. “One day when Rav Frank came to deliver a shiur in the yeshivah, he suddenly turned to Rav Rosenthal and demanded, ‘What’s Rav Ovadiah doing here?’ ‘What do you mean?’ Rav Rosenthal said. ‘You ordered me to set him up here.’ Rav Frank replied, ‘That’s indeed what I said, but I meant that you should pay him to learn at home. The time it takes him to walk here is bittul Torah.’”

Generation Gap

While their relationship is close today, Rav Avraham and Rav Moshe represent two completely different periods in the life of Maran Rav Ovadiah Yosef. While Rav Avraham was born back when the family lived in Egypt and his father was a young rav struggling for his daily bread, Rav Moshe was born to a famous and important rav and posek.

“When we lived in Beer Sheva,” Rav Avraham recounts, “my older brother Rav Yaakov ztz”l and I learned in Rav David Nachman Bloi’s Yeshivas Hamsmidim. Occasionally we’d get prizes, and everyone could choose what they wanted. And what did we ask for? Pen refills and blank sheets of paper. We would bring our prizes home and proudly give them over to Abba so he’d have something to write his chiddushim with. We were so poor then that we didn’t have extra paper in the house — when Abba would need to revise something, instead of writing a new draft, he’d cut out the relevant paragraphs and tape them together.”

By the time Rav Moshe was born in 1966, however, Rav Ovadiah was already a venerated dayan and posek, and became the country’s Sephardi chief rabbi when Moshe was seven.

“There was always a feeling of awe, of respect,” Rav Moshe recalls, but as the youngest, I think I had a certain closeness that evaded the others. I’d go around with him almost every day, accompanying him when he’d return from his lectures and shiurim around the country. It was usually around midnight or later. It started when I was just a boy and continued when I was a bochur. We’d take walks together around the neighborhood, when the streets were deserted.”

“There’s one thing that sets Rav Moshe apart from all the other brothers,” says Rav Avraham. “And I envy him for that. He merited to learn with Abba regularly. While I was pretty much afraid of Abba, Moshe was much more open with him.”

Moshe agrees that it’s true. “By the time I was a bochur, most of my siblings had already moved out, so at Shabbat seudot, for example, while my siblings remember the spirited singing — and Abba’s taste in music was well-known — we’d often sit alone and learn together instead.”

While the rest of the family lived in Jerusalem, Rav Avraham went to learn in Tel Aviv as a bochur beginning in 1967. The following year, Rav Ovadiah was appointed Sephardic chief rabbi of Tel Aviv, and the family moved to the coastal city. “Those years in Tel Aviv,” says Rav Avraham with no small amount of nostalgia, “we’d take walks along the beach together at night. That’s when I was closest to Abba. But later, after I had my own family, the distance returned, to the extent that when I came to visit, I would actually make an ‘appointment’ with Ima. Ima allotted us a quarter of an hour — she was like the general in charge of his time, protecting him against frivolity, and my kids would always prepare a written list of the questions they wanted to ask him. Abba enjoyed their company so much that when Ima would come in to say, ‘Come, let’s not bother your grandfather,’ he would say, ‘Leave us be for a few more minutes, I’m enjoying them.’ ”

Never Neglected

Rav Ovadiah never squandered a minute, and while some therapists today might consider that emotionally crippling for kids, the Yosef children, especially the older ones, took it in stride. That was their Abba, and even the toddlers made it work. Rav Avraham remembers how his father would feed him and his siblings when they were little:

“Abba’s sitting, his eyes glued to a sefer, and in his free hand he holds a spoon. He dips it in the plate, lifts it up, and one child comes up and takes a spoonful. He dips it in the plate again and another child comes up for a spoonful.”

But they never felt neglected — and they even had another “father” to step in if need be. For ten years, Chacham Ben Zion Abba Shaul lived in the same building — two gedolei Torah who lived side by side and were best friends.

“When Rav Ben Zion died and my father eulogized him with the words, ‘He was like a father to my children,’ he was referring to me,” says Rav Avraham. “Chacham Ben Zion was involved in every meaningful part of my life as a kid.”

He remembers one Friday when they were playing outside and someone threw a stone that hit him straight in the forehead. “My mother saw my whole face covered in blood and thought it had taken out my eye, and she started to scream,” Rav Avraham related. “My father didn’t hear anything, but Rav Ben Zion ran down, washed my face and calmed everyone down. Then he rushed me over to Bikur Cholim hospital. By the time we came back, it was already shkiah, and he said to me, ‘you must be cold’ and wrapped me in his coat. Year later I realized that his coat pockets were full of muktzeh, so it was preferable that I, a child, should wear it.

“We came to the shul that was in the basement under our house,” Rav Avraham continues, “and Rav Ben Zion told me, ‘Wait, don’t go in yet.’ He knew Abba was strict about me coming to shul on time, so he went in first and explained to Abba what happened, then signaled for me to enter, my eye covered in a hospital bandage. After the davening Abba didn’t say a word, but I can still feel his affectionate caress.”

Raising the Bar

Rav Ovadiah didn’t need to “do” chinuch, Rav Moshe explains. “He just provided an example. When you looked at him, you knew exactly what was right and what was wrong. He hardly every directly interfered, but all of us lived under his sharp eye — although admittedly my older brothers bore more of the brunt of his scrutiny.

“But Abba always raised us to be ambitious,” Rav Moshe adds. “To demand a lot from ourselves, to always want to learn and understand more. To always grow in Torah. He demanded that we know how to write our own chiddushim.”

Yes, Rav Avraham agrees, “he would give us prizes for that. I have a sefer with a dedication he wrote me from when I came to him to be tested on a certain perek in Bava Metzia. I also remember that when I was six I brought Abba a photograph of myself standing next to the teacher and giving a derashah to the entire class. Abba kissed me in response. I’ll never forget that.”

The two also remember how for years, their father would gather his daughters together for in-depth Tanach shiurim. “I used to come from Holon to take part,” Rav Yosef says, and Rav Moshe recounts that he still has notes from those classes, which he one day hopes to edit and publish.

Unsung Heroine

As the brothers reminisce about Abba, they realize they can’t omit the central linchpin in the responsible for who Rav Ovadiah was: Ima, Rabbanit Margalit.

One Erev Pesach, a certain rav went in to Rav Ovadiah to ask him a halachic question, Rav Avraham remembers. “They talked at length in learning, and then the rav said to Abba: ‘Kol hakavod that the Rav is sitting and learning even on Erev Pesach.’ ‘Kol hakavod to me?’ Abba cried out, ‘The honor belongs to my wife who makes it possible!’ ”

“This wasn’t just a pretense. Abba respected Ima so much,” Rav Moshe notes. “He had a real reverence for her for enabling him to concentrate on his learning like that. And she was the watchman. Ima always waited for Abba at night. It didn’t matter at what time he came back — she was always awake. It was important to her that he shouldn’t come home to an empty house. She always got him a drink or a cup of tea.”

Rav Avraham’s voice breaks as he describes the yearly ritual on Erev Yom Kippur. “When Ima and Abba approached each other to ask each other for mechilah, you could have thought that these were two people who had been waging a bitter feud. Abba would sob and say, ‘Forgive me, I didn’t treat you respectfully enough.’ And Ima would stand in front of him and cry, ‘Forgive me, Chacham, I should have helped you more.’ I think more than anything, that’s the lesson we’ve taken away.”

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 881)

Oops! We could not locate your form.