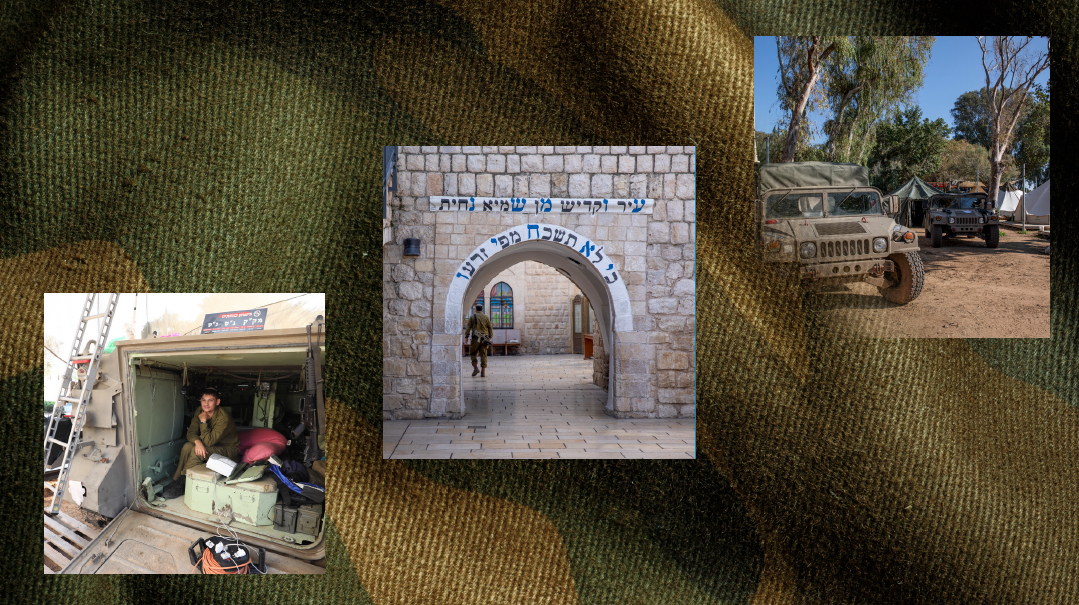

Northern Watch

Israel's once-pastoral north is now a tense military zone

Photos: Menachem Kalish

E

ven as we approach the guard post, we can feel eyes upon us.

In place of the regular security guard stationed at the entrance to this small northern yishuv, we’re stopped by an inquisitive reservist shouldering a rifle. Judging by his questions, you’d think we were entering a high-security military installation. With the northern border region under Hezbollah’s guns, only residents and their guests are permitted entry.

Ultimately, after a stern warning not to disclose the name of the yishuv or anything about military positions, I’m waved through. The yellow gate slides open, and I’m inside.

After a long drive around the community and several conversations with owners of bed-and-breakfasts, who all lamented the absence of vacationers due to the security situation, I understand why I’ve been allowed in; other than the briefest glimpse of a green Humvee behind a fluttering tarp, outside the yishuv’s fence, there isn’t much to see.

On the way out, I again encounter the stone-faced reservist stationed at the front gate.

“Remember what I said, yeah?” he warns, wearing a serious expression.

In a region on the brink of war — where Hezbollah has repeatedly struck civilians well away from the border — the security is unusually high. Military censor rules dictate a total anonymization of reporting.

Heading out into the fields surrounding the yishuv, there’s evidence of the militarization of the region, normally associated with tourism and agriculture.

Behind a warehouse wall is concealed a convoy of military vehicles. Next to them, soldiers load and unload equipment. The growl of engines is heard in the background.

Heading down a dirt path into the wooded area, a commander rushes toward us: We’re not to take a single photo. A few moments after being shooed off, we discover a clearing in the forest where the tracks of tanks and other heavy military vehicles have furrowed the ground.

“Until a week ago, all kinds of military vehicles were stationed here,” one resident of the nearby community says.

The tense atmosphere and the movement of army vehicles intensifies around noon, when the assassination of Wissam al-Tawil is announced. Just one month ago, al-Tawil was appointed commander of the elite Unit 22 of Hezbollah’s Radwan force.

Forty missiles were fired the preceding Shabbos at the “eyes of the state,” the Israeli Air Force control base on Mount Meron. The man responsible for the massive attack was Wissam al-Tawil, the senior Hezbollah operative assassinated the following Monday. Photos from the preparations for the 2006 murder and abduction of two IDF soldiers, Ehud Goldwasser and Eldad Regev, reveal Tawil was an integral part of the task force responsible for planning and carrying out the murderous mission, which triggered the Second Lebanon War.

In recent weeks, attacks on Israel have come from the Syrian border as well. Most of the missiles were intercepted or fell in open areas, and the IDF attacked the launch sites. In an unusual step, the IDF claimed responsibility last Monday afternoon for the killing of Hassan Okasha, responsible for Hamas rocket launches from Syria.

On Tuesday evening, the IDF claim responsibility for another targeted killing: Ali Hossein Barji, commander of Hezbollah’s aerial forces in southern Lebanon, assassinated at Tawil’s funeral. Per the IDF’s statement, the assassination was carried out by an IAF aircraft.

The fear of an escalation in the north grows with every round of strike and counter-strike. The tension evident among troops across the Galil shows that while all eyes are focused on Gaza, Israel’s north is a tinderbox.

Running on Low Heat

Heading to Tzfas, where sirens cut through the air on Shabbos morning, I find a city that has remained relatively quiet until now.

“We’ve had maybe three or four sirens since the beginning of the war,” says Shimon Avraham, a resident of the city we meet at the Chabad shul. “But the panic was real.”

“My son became bar mitzvah this week and had his aliyah on Shabbos, but he almost refused to go to shul out of fear,” says Tzfas resident Mordechai Kashmacher.

He invites me to his art gallery on Beit Yosef Street in the Old City. Unlike on normal days, there’s plenty of parking. On my last visit to the city a few years ago, Avraham Sadeh Square, which leads to the largest Judaica retail street in the world, served as a tourist bus parking lot. It’s now been converted into an observatory, and students from the college occupy the remaining spots.

“Those parking spots could have been reserved for the ‘heavy’ [big spending] tourists,” grumbles one business owner. He ducks into the doorway of his establishment: “I just came to get something. There’s no point in coming to work.” He slams the door.

In fact, Beit Yosef Street, the hub of Tzfas’s Judaica trade, is practically closed off. Kashmacher beckons us into his massive gallery, where he keeps up the tradition of his late father, Rabbi Yaakov, who was one of the greatest chareidi artists in this Kabbalistic city.

Above the gallery is the Sanz shul; minyanim are relatively sparse. There’s no domestic tourists, never mind foreign visitors. Stores throughout Tzfas, some of which cater to the local population, are keeping the thermostats set low. Businesses dedicated to tourism are eligible for compensation from the government during economic downturns triggered by national emergencies. But Tzfas, oddly enough, is not on the Tourism Ministry’s list. As far back as the Covid epidemic, community leaders promised to get Tzfas registered as a tourist city, but nothing has come of it as yet.

“There are no tourists, no vacationers, but somehow, we’re staying afloat,” the owner of a dairy restaurant tells us. “When will we get government compensation? No idea. In the meantime, we’re holding on.”

But in Tzfas’s artists quarter, shutters are closed. Some owners have painted or covered over their signs, to avoid having to pay the municipal signage fee.

“In fact, since Covid, our situation has gotten worse,” Kashmacher says. “The tourists left, and most of them didn’t return. And the trickle has dried out completely since the fighting began. You’d think they would bring in entrepreneurs and donors, maybe even set up a website to promote the unique galleries here. But so far that’s not happening.”

“The livelihood of most of the chareidi residents here depends on the educational system and tourism,” says Tzfas city councilman Nachman Gelbach. “The tourism industry includes eateries, guesthouses, and related occupations like construction, brokers for tzimmerim , and housecleaning. The first blow was Covid. Now it’s happening all over again.

“The government must come to its senses and respond to the needs here, even though the damage is hard to measure and Tzfas is not on the front line of the conflict. There must be recognition of the damage the city has suffered.”

Hearing the Booms

The day after I toured the Biriya Forest Promenade near Tzfas — packed with residents out for a stroll — the site again became a target for Hezbollah attacks. The p romenade stretches from the Ibikur neighborhood to the army’s Northern Command base (Camp Dado). A suicide drone exploded in the base’s parking lot, causing only minor damage to an exterior wall and a small fire. B’chasdei Hashem, there were no casualties.

The drone attack was carried out “in response to the crime of the assassination of the great leader of the martyrs, Sheikh Saleh al-Arouri, and his brother in the southern suburbs of Beirut and the crime of the assassination of the leader of the martyrs, Brother Wissam Al-Tawil,” Hezbollah stated. “The resistance in Lebanon targeted the headquarters of the Northern Command of the enemy army in the occupied city of Tzfas.”

The attack was another reminder of Hezbollah’s long reach.

How prepared is Tzfas for a missile attack? According to the town’s mayor Shuki Ohana, “We’ve been thoroughly planning for all kinds of disasters for a long time, but especially since the outbreak of the war. We’re preparing by providing shelters to educational institutions and public buildings, and we hold meetings with the defense establishment and the Home Front Command on an almost daily basis. The residents receive instructions from the municipality passed down to us from the army.”

Ohana is far from circumspect when asked how he thinks Israel should respond to Hezbollah’s attacks.

“This is a time for bold decisions,” says the mayor. “The government must make the political decision to push the security zone, which now, sadly, is inside Israeli territory, back into southern Lebanon. We must move the front from the evacuated settlements near the border, deep into southern Lebanon, and force Hezbollah and the Radwan forces back across the Litani River. A terrorist organization that operates as an army, for all intents and purposes, and freely targets civilians, must face a military response.”

Near city hall we meet Yossi Kakon, the chareidi candidate for mayor in the next elections.

“We’re in a time of great tension,” he says. “Every time Iron Dome intercepts a missile headed for the Tzfas area, it’s clearly audible. We don’t get a lot of sirens, but we hear the interceptions and impacts very clearly. At night and in the quiet hours, we hear the echoes of the bombings at the border.”

Kakon’s activities have been focused on the civilian response. “Since Simchas Torah, we’ve established a civilian headquarters to provide a variety of services, including humanitarian assistance, as well as referring families in need to welfare organizations and associations, using the connections I’ve forged over the years with various government ministers. I’ve just returned from over a month and a half of reserve duty. I saw the dedication and heroism up close. Everyone feels the spirit of unity, and it’s a spirit no one will break.”

He, too, addresses the tourism industry that’s so essential to the city’s economy. “Tzfas is a de facto tourist city, even though it’s not listed as such. A 3,000-year-old city that’s home to some of the most ancient shuls deserves to be classified as a tourist city. But in practice, tourism here is underdeveloped. One of my goals is to breathe life into the city’s tourism industry, to make it a driver for growth and prosperity. The potential is enormous and unrealized, and there’s definitely a lot of work to be done in this area.”

As we stroll down the pedestrian mall, we run into a group of young secular residents, who greet Kakon warmly. Some of them, I learn, regularly join his tours of the city.

“We have to take care of the economic and tourist development of the city,” Nir Dahan, a young local, tells us. “Our city deserves to be on the map, and to have a rich cultural and community life. And of course, we need security, both economically and in terms of personal safety.”

Kever Rashbi Still Packed

A pleasant sun greets me on the ascent to Meron. There’s not a single unoccupied parking spot. The tziyun itself is packed. The tension boiling outside all week is seemingly not felt within Rashbi’s tziyun. Inside, the tefillah carries on as usual. No one mentions the security situation.

Outside, a group of avreichim stand sipping coffee. A loiterer on a bench nearby provides an update on the assassination of a senior Hezbollah official.

A bearded Meron resident addresses the avreichim in Yerushalmi Yiddish: “What, you think there’s enough room here for everyone? It’s a miracle that it’s not full now, otherwise the police would have already closed all the roads to the yishuv.”

I ask him what can be done if the demand exceeds the supply.

“Simple. Set up shelters.”

I ask him if, despite the strong turnout for tefillah, tourism has nevertheless felt the pinch.

“You could say that,” he says. “Many people still come, especially for Shabbos. But after this Shabbos, I don’t know anymore.

“Kedai hu Rabi Shimon…” he concludes, hopefully citing the Gemara’s dictum about relying on the Tanna Bar Yochai in a time of distress.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 995)

Oops! We could not locate your form.