Northern Sanctum

| November 22, 2022Copenhagen celebrates 400 years of Jewish history

Photos: MB Goldstein

Copenhagen might not appear on your travel itinerary, even if you consider yourself an expert on Jewish heritage in Europe. That’s a shame, because although it’s out of the way, and was never a major center of Torah learning on the global scene, its 400 years of Jewish history — commemorated last week with the Danish queen’s appearance at a special service — are still absorbed in the city’s landmarks and in its struggling but determined community

We’re strolling through an upscale shopping district in the center of Copenhagen, Denmark.

The city is European to the hilt, yet something casual — Scandinavian — tells you this is Northern Europe, with light sweaters draped over shoulders more common than the classic elegant European scarf and brooch at the neck. The city’s modern streets with their wide bike lanes accommodate the swarms of straight-backed cyclists, but we’ve gotten off a city boat ride and are walking through a cobblestoned pedestrian mall past the Prada fountain and the Louis Vuitton department store.

Tourists and locals mingle outdoors, and we stop to buy cold water and sit on a bench. Opposite, under the arches of the stores, an artist sells his hand-painted pictures of Danish fishing cottages, while a dark-skinned woman in a headscarf sits on the ground near a tray filled with kroner.

With all the buzz around us, it takes a few seconds to realize we’re right at the landmark we were seeking: Copenhagen’s famous Rundetårn, or Round Tower, is towering over us right on the street corner. At 34.8 meters high, it overlooks the narrow streets, and a steady trickle of tourists are paying 40 kroner to ascend the round ramps inside and tour the oldest observatory still functioning in Europe. The Rundetårn, overlooking the city’s rooftops, has been an active observatory since 1635, famous for hosting the discoveries of that century’s premier astronomer, Tycho Brahe.

We’re going to climb it too, but we’re especially interested in understanding a mystery that few natives or tourists know much about. Craning our necks from across the street, we can see the large gilt rebus, drafted by King Christian IV, ruler of Denmark and Norway, with the words he himself wrote in a combination of letters and symbols that state: “Lead, G-d [written in four Hebrew letters], learning and justice into the heart of the crowned King Christian IV.” Why, in this Northern European city, remote from centers of the Jewish world, is this building — and two others in the city — inscribed in Hebrew with the four-letter-name of Hashem?

Doctor’s Orders

The Jewish community of Copenhagen may be miniscule today, but it has a rich and ancient history, beginning in 1612 under the reign of King Christian IV. Wanting to attract merchants and trade to his kingdom, the king offered a letter of protection to a Portuguese Jew named Albert Dionis, who was living in Hamburg and did business with the Danish king from there. Ten years later, the king issued a letter of protection for all Jews, which meant that they began to trade, travel and settle in this northern kingdom.

Denmark’s only land border is with Germany — Copenhagen is about 200 miles from Hamburg, and at times Northern Germany was under Danish rule — but it is linguistically, ethnically, and sociologically related more closely to its Scandinavian cousins, Sweden and Norway, just across the sea. The Danish kingdom has a history of tolerance toward Jews, at odds with the rest of Europe’s tides of relentless religious persecution, pogroms and expulsions. There were no ghettos or limitations on Jewish trade and professional admittance. Orthodox Jewish diarist Gluckel of Hameln (1646–1724) who traded in Denmark, writes of the king’s tolerance and records that one of her 14 children married and settled there.

Four hundred years later, Eli and Therese Katzenstein are pillars of Copenhagen’s tiny Machsike Hadas community, happy to meet with us and discuss the community’s origins. “The Danish king invited Portuguese Jews to move from Amsterdam and settle here in 1622, out of a strong desire to develop the Danish economy,” Mr. Katzenstein explains. “Jews were being persecuted across Europe during the 17th century — for example, the Chmielniki massacres of 1648 and 1649 – yet under the King’s protection, Denmark was the most peaceful haven a Jew could hope for in Europe. And slowly, a community — mostly from Amsterdam — was attracted to settle here.”

King Christian IV also summoned a Portuguese Jewish physician and Torah scholar named Rabbi Binyamin Mutzafi (author of Mossif Ha’aruch on the well-known Sefer Ha’aruch, and a brother of Albert Dionis, who changed his name several times while outrunning the Portuguese Inquisition) from Amsterdam to serve as court physician.

“Rabbi Mutzafi was asked by the king to remain here in Copenhagen, and had an influence on the court and the society,” says Katzenstein. It was likely under his influence that Hashem’s name appears on those buildings, and that coins were actually minted with Hashem’s name. Another long-lasting imprint of Rabbi Mutzafi was the Danish law, still valid today, that bris milah can only be performed with a qualified medical doctor in attendance. After the king died, Rabbi Mutzafi returned to Amsterdam where he became chief rabbi.

The building next to the Machsike Hadas shul once served the occupying Nazi forces, and many years later, a kollel. Today it’s where Chabad shaliach Rabbi Yitzi Lowenthal is working hard to maintain the strongest Jewish presence in Scandinavia

Standing Guard

The Machsike Hadas shul, where Copenhagen’s stalwart adherents to halachah and tradition staked their own holy ground, is on a city street lined by tall, conjoined apartment buildings, without so much as a patch of grass or a tree anywhere. It’s just a short walk away from the central museums and Rosenborg Palace. Today, the Chabad house is adjacent to Machsike Hadas, and the Chabad shaliach, London-born Rabbi Yitzi Lowenthal, is its rabbi.

These two addresses are the center of religious life here today. Some Israelis wave us in through the door marked “Chabad Huset,” and we meet the energetic Chabad couple and their children.

From 1940 to 1945, this four-story building next door to Machsike Hadas was among the public school buildings requisitioned as sleeping quarters for the Nazi forces who occupied the city. Mr. Jitzchok Arjeh (Leo) Samson, a Copenhagen old-timer who ran the community’s kosher grocery before his move to London, remembers “the black and white striped sentry box with the German soldier and his rifle standing guard outside the barracks a few meters from the Machsike Hadas shul. Yet we continued to go to shul and they never raised a finger against the Jews or the shul.”

Many years later, the building was acquired by community leader Erik Guttermann, a sixth-generation Orthodox Danish Jew, who used it to house a yeshivah for Russian bochurim during the 1990s. We pay a visit to Mrs. Guttermann, a doyenne of Copenhagen’s frum community, to get a feel for the atmosphere and history.

“One day my husband said to me, ‘You’re going to have 20 more kids soon,’ and he established a yeshivah here for a few dozen Russian bochurim,” recalls Mrs. Guttermann. “For around five years, we had the boys here, offering them a yeshivah education which enabled them to continue to Chaim Berlin, the Mir, and other top-tier yeshivos.”

Erik Guttermann was a man of many ideas, including buying a hotel and building a shul in Hornbæk, on the Danish coast, which he hoped would attract Jewish tourists. Mrs. Guttermann tells us about the challenges of raising her frum family in what even then was a small, out-of-the-way community. Once married, all but one of her five children eventually moved away to take up opportunities in larger communities. Her son, Rabbi Chaim Michoel Guttermann, is the well-known director of the Shuvu network in Eretz Yisrael.

While most of the progeny of the old-time frum families have moved away, the Lowenthals work hard to maintain the strongest Jewish presence in Scandinavia, running a kosher restaurant, a preschool, shiurim, a cheder, minyanim and Shabbos meals.

“Between locals, guests, and students, we still schedule, and often get, daily minyanim, morning and evening,” Rabbi Lowenthal says, noting that they often have up to a hundred guests for Shabbos meals. He leads us through a back courtyard — where we’re surprised to find six friendly Danish policemen sitting and drinking coffee — to the building next door: the Machsike Hadas of Copenhagen. Well-kept and traditionally furnished in warm wood tones, the shul’s narrow width gives us the impression of a townhouse, or maybe a small museum. I know that the Machsike Hadas community had prominent rabbanim and its own shechitah in the past (a large wall plaque records members who have passed away, and we can spot familiar family names like Winkler and Guttermann), so it’s a bit surprising that there are a total of only 84 seats in the men’s section, while the ladies’ gallery is even smaller.

Rabbi Lowenthal shows us an old, thin shofar typical of old Ashkenazi shuls, as well as the wimpels that are dedicated to the shul when a yekkish boy turns three. The one he unfurls for us was embroidered in 1898. I spy a siddur translated into Danish, and inquire about any special local minhagim. The Danish community is proud of its centuries-old traditional tunes stemming from the German community of Altona, a city near Hamburg that was Danish territory back in the day. They still patiently recite many piyutim on Yom Tov, and maintain an Ashkenazi custom of reciting Anim Zemiros after Shacharis every single day of the year.

The main Krystalgade shul tried to bridge the old and the new, but innovation alienated the more traditional Yidden. Seven years ago, it was the site of a terrorist attack, and has police protection ever since.

Modern Winds

The weather is pleasant and cool, perfect for hiking around a fairly compact city, although we do need to be careful not to get run over by bikes. Copenhagen’s central synagogue is an impressive building on a narrow street called Krystalgade. The stucco walls may look strong and solid, but unfortunately have not stood firm against the tides of modernity. Opposite, diners sit at tables on the sidewalk, enjoying their Smørrebrød (an open-topped buttered rye sandwich, usually with cold cuts) and beers. A police car is patiently parked outside the shul gates, deployed permanently by the Danish government since the terrorist shooting of 2015.

Closeted under the aron kodesh of the large sanctuary, there are close to 100 sifrei Torah, some of them up to 400 years old, and others brought here from now-extinct Jewish communities in the Danish provinces, places like Jutland and Odense. The shul also owns a rare 17th century “sefer Torah-style” rolled up parchment of Neviim used for leining the haftarah with precision, as it contains the nekudos and taamim in it. There are other scrolls that were rescued from the famous fire that engulfed the original shul in 1795.

The story of the fire goes back deep into the annals of the community. Permission to build a synagogue was granted by the Danish kingdom in 1680. In 1770, almost a century later, the community hired a rabbi from Prussia by the name of Rav Gedalia Levin, who desperately warned his community against bowing to modernity and changing Jewish tradition. If they did not remain loyal to Torah, he said, a fire would destroy the community. In 1795, two years after Rav Gedalia’s passing, a fierce blaze swept through the Jewish quarter and the shul. His son and successor, Rav Avraham Gedalia (who is mentioned in approbations to contemporary sefarim printed in Hamburg), stood in prayer at the entrance of the shul, and instructed his son to enter and rescue the sifrei Torah. As soon as they were removed from the burning building, it collapsed.

After this, tefillos continued in dozens of homes and small, private shuls throughout the city, until the synagogue still standing in Krystalgade was consecrated in 1833. The chosen rabbi of the new shul was Rabbi Dr. Avraham Alexander Wolff, a talmid of Rav Yaakov Tzvi Mecklenburg, author of the encyclopedic Kesav Vekabbalah.

“Rabbi Wolff was a tremendous baki and talmid chacham,” explains Copenhagen-born scholar Rabbi Gil Sasson. “His teshuvos show how clear and firm he was on halachah, and he was widely respected in Europe. Yet, he was a controversial figure because while he didn’t deviate from halachah, he did change the Ashkenaz mesorah of the shul by omitting piyutim and changing the seating. He also wrote a hymn and various zemiros in Danish that were sung after the derashah in shul — and are still sung by the choir in Krystalgade today — but this alienated the more traditional Yidden, who feared the innovation.”

(Rav Shalom Shachne, Rav Avraham Gedalia’s son, was a posek in constant correspondence with Rav Akiva Eiger, but although he lived in Copenhagen, he never officially served as rav of the city. He passed away in 1840, toward the beginning of the tumultuous tenure of Rabbi Dr. Wolff.)

After the great rabbinical courts of Germany published a kuntress called Eilu Divrei Habris, which contained a prohibition against translating the davening in order to stem the Reform/Haskalah influence, Rabbi Wolf’s Danish hymns were seen as a provocation.

“My great-great-grandfather Moses Levy [1795–1865] was an uncompromising champion of religious tradition in the prolonged confrontation between tradition and modernity in the Jewish community of Denmark,” says Jan Meyer, an Orthodox lawyer in Teaneck, New Jersey, and a proud Jewish son of Copenhagen. According to his great-great-grandson, Moses, a successful businessman, grew up at a time of pervasive assimilation and conversions, and was deeply concerned for the survival of religious Jewish life in Denmark — and in his own family.

He waged a lifelong battle against Chief Rabbi Wolff, and refused to attend the main shul. Instead, he purchased a building at 5 Læderstræde, where he established a synagogue for his family and a small group of followers.

Speaking over the phone from New Jersey, Jan directs us carefully from the Rundetarn back toward the most exclusive of the shopping streets and the stork fountain. It’s clear that he knows his native city like the palm of his hand and enjoys sharing its stories. Turning the corner at Hermes, we find ourselves on Læderstræde. Here, at number five, a shul functioned daily from 1845 until the 1960s (excluding the years 1943 to 1945, when the occupying Nazis prepared to round up the Jews and in a famed Rosh Hashanah midnight miracle, 7,000 of them were smuggled across the Oresund Strait to Sweden by righteous Danish resistance members and Danish fishermen). The shul was untouched while the family was in Sweden, and upon their return, was used by the entire community until the great synagogue was renovated. We look for Jewish names on the neighboring doors, but they are all unmistakably Danish.

Jan directs us to walk through the dusty foyer to see where a special extension housed the succah. “From 1845 until 1910, there were only two synagogues in Copenhagen: Krystalgade, with 1,000 seats, and my family’s shul,” Jan explains. His great-great- grandfather even wrote to the king to ask his help in reining in Chief Rabbi Wolff’s modernization measures. When it was time for his only child, Helene, to marry, Moses Levy brought a talmid of the yeshivah of Rav Jacob Ettlinger (the Aruch Laner) in Altona over to Denmark to marry her.

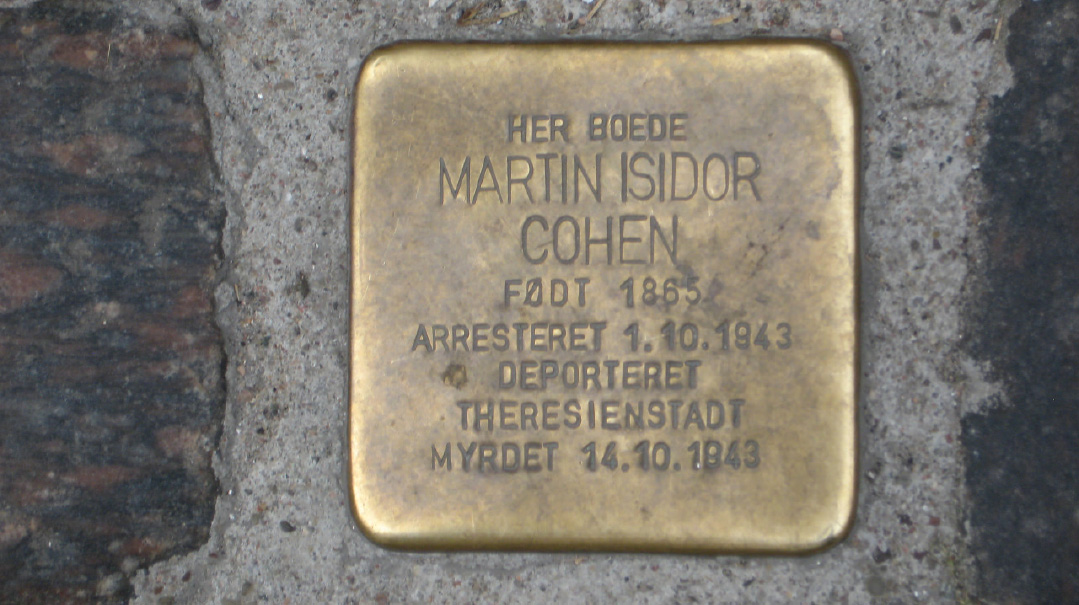

While most of Danish Jewry was spirited away to Sweden by righteous gentiles, not everyone escaped. Memorial tiles on the sidewalk outside the shul testify to a frightening few years

Fighting for Tradition

They had come for the trading opportunities, and stayed for the civilized atmosphere of tolerance and friendship, yet these freedoms would eventually be the downfall of the Danish Jewish community. The Reform movement made its way over from Germany, and many Jews who fled persecution in Eastern Europe let go of their tenacious hold onto Yiddishkeit once faced with freedom. Assimilation into Danish society and intermarriage with the friendly locals were the tragic order of the day, and many expected the rabbis to legitimize nominal conversions and welcome children of mixed marriages into the community.

Later waves of immigration from Russia and the Balkans, following pogroms of the early 20th century, saw another influx of refugees. Some were in transit to America, but remained in Copenhagen when they could not afford to buy tickets for the next leg. Today’s Danish Jews are mostly of Russian descent, rather than the earlier “Viking Jewish” families.

In 1910, an explosive court case rocked the Jewish communities of Northern Europe, when the Danish community wanted their chief rabbi, Rabbi Tuvia Lowenstein, to sanction the admission of non-halachic Jews to the kehillah. When Rabbi Lowenstein, a talmid chacham of stature and man of principle, consulted the son of Rav Yitzchak Elchanan Spektor, av beis din of Kovno, the gadol responded with a letter containing very lenient halachic rulings for him to abide by given the unique circumstances. This was not good enough for the liberals of the Krystalgade congregation, though; they brought in a junior rabbi to undermine and overrule Rabbi Lowenstein. In a highly-publicized case decided in the Danish High Court, it was decided that, as Rabbi Lowenstein had been hired as an Orthodox clergyman to uphold Jewish Orthodoxy, he was entitled to do so. While Rabbi Lowenstein was awarded a large sum in compensation, the damage to the community’s fabric seemed to be beyond repair.

A small minyan followed Rabbi Lowenstein to daven in his house, but in 1913, when he was soon invited to lead the prestigious Yekkishe community (IRG) in Zurich, Switzerland, he left Copenhagen and its rifts behind. The dozen families of loyalists could not attend services in Krystalgade, and for three years they tried organizing their own kehillah, but, explains Eli Katzenstein, “They were desperately poor. My own grandfather had just arrived in 1909, and it took until 1916 for them to organize their own community, which eventually morphed into Machsike Hadas, and hire a rav.”

Machsike Hadas grew, attracting both families from the main community and new immigrants. Its first rabbi was Rav Michoel Shalom Winkler (grandfather of Rabbi Shimshon Winkler, rav of the English-speaking community in Romema, Jerusalem), born in the Old Yishuv of Jerusalem and a talmid of Rav Yosef Chaim Sonnenfeld. In 1932, Rav Winkler traveled to New York to raise funds to establish a yeshivah in Denmark. Unfortunately, he didn’t succeed in this mission, and unable to collect enough money for the return trip to Denmark, Rav Winkler stayed in New York, where he was niftar and buried several months later.

During Denmark’s “golden era” of the 1930s, 50 or 60 large frum families formed a strong nucleus, maintaining their own cheder and shechitah, under the leadership of Rabbi Wolf (Binyamin Zev) Yakovson, a German-born Agudas Yisrael leader who would later partner with Rav Shlome Wolbe in Lidingö, Sweden, to create a girls’ seminary for Holocaust survivors. From 1933, when shechitah was forbidden in Germany under Nazi rule, the Jews of Germany’s northern towns were occasionally able to smuggle in kosher chicken from Copenhagen.

“Most Jews here were not yeshivah-educated,” Eli Katzenstein explains, “but Machsike Hadas Jews were very erlich, and were supporters of Torah.” Later, for three years from 1959 to 1962, the city hosted its own yeshivah led by Rabbi Ezriel Chaikin from Belarus, but the numbers soon began to decline. Rabbi Dov Steinhouse served as rav for a while, then left to Yeshivas Kol Torah in Jerusalem, and Rav Chaikin took over in his place. The main community continued a half-hearted struggle against assimilation and intermarriage, while many mainstay families left for larger frum communities across Eretz Yisrael and Europe. By the 1970s, Machsike Hadas families like the Samsons, Katzensteins, and Guttermanns had to send their children away for Jewish schooling abroad — and the boys who were sent to learn abroad didn’t return. During the 1980s and 1990s, Eric Gutterman’s community kollel and yeshivah for Russian bochurim brought new life and some good times locally, but were not sustainable in the long-term.

“By the time we arrived in 1996, many of the Machsike Hadas original members had left,” says Rabbi Lowenthal.

“Jews were being persecuted across Europe, yet under the King’s protection, Denmark was the most peaceful haven a Jew could hope for.” Mr. Eli Katzenstein, a pillar of the Machsike Hadas kehillah, is doing his part in holding the miniscule kehillah together

Still Proud

With only a mini-deli remaining after the Samson’s kosher market closed down, kosher groceries are available by online order and delivery from Antwerp, Belgium, and the Chabad restaurant is open daily in the evenings. There is no kosher bakery. In fact, we’ve brought along a gift of some kosher Danishes for our hosts, because “you can’t get a kosher Danish in Denmark.”

Muslim immigration to Denmark has raised other issues, as it has all across Europe. In 2015, a terrorist attacked the community during a bat mitzvah celebration at the Krystalgade synagogue, where a Jewish security guard outside was murdered.

“The Danish people were in shock at these attacks, and spend hundreds of millions of kroner to protect the synagogues and community,” says Katzenstein. And while the presence of police cars and the high fences outside the synagogue are intended to reassure, the effect is, honestly, depressing. The Danes may be tolerant by nature and tradition, but as a result of their immigration policies, Katzenstein now refrains from walking to shul on Shabbos wearing a black hat, opting for a flat cap instead. As for us, we get only one random “Shalom” on our bus and boat treks through the city, but are glad that we don’t run into any hate either.

As with any dwindling Jewish community, the impact and importance of Danish Jewry cannot be measured by its numbers or the tangible traces left in the country, but in the lessons of its past and in the strengths of the proud members who carry its essence into their Jewish future.

TWO SIDES OF THE COIN

Sitting in the Chabad Huset with coffee and cinnamon buns freshly baked by Rebbetzin Lowenthal, we’re happy to meet and chat with an Israeli expat who’s brought along a real collector’s item: a centuries-old original Danish coin, with Hashem’s name engraved on its face.

How did the Tetragrammaton, Hashem’s name of four letters, find their way onto Scandanavian coins hundreds of years ago? Sweden minted a coin with the Hebrew letters of G-d’s name in about the year 1568; Scotland did so in about 1591; and around 1600, Sweden’s King Charles IX had a valuable gold coin with those holy letters minted in gold. But the most popular and enduring coins are known from the time of Christian IV, the king of Denmark and Norway, who ruled from 1588 to 1648. By the mid-17th century, these coins found their way into Poland, Switzerland, and Germany as well.

But how is a coin with Hashem’s holy name on it treated in halachah? The Shulchan Aruch (Orach Chaim 334:21) writes that if a fire breaks out on Shabbos, kisvei kodesh [holy writings] may be saved. However, if a sefer Torah written by a heretic is in danger, it should not be saved but left to burn, since it anyway should be burned.

The Mishnah Berurah there quotes from the Taz, that coins with Hashem’s name should also not be rescued but be left in the fire to melt, for the same reason. But then he questions this, saying that perhaps the name was not written on it for heretical purposes, and therefore should not be left to melt.

Yet the Chavos Yair contends that even if not minted by heretics, it is permitted to melt “the Swedish coins” since they are not made for any holy purpose, but just meant to be used as currency, and the Pri Megadim makes this point too.

Since the coins were minted by King Christian IV and in use at the time of the Dano-Swedish wars, this reference to Swedish coins is generally understood to refer to the Danish currency inspired by Rabbi Mutzafi’s influence on the king, and relying on the above opinions, it seems that the coins have no kedushah — meaning that the name on them can be erased, and they can be taken into the bathroom. That is, if you can find one. Unless you know a friendly archaeologist who can dig one up for you in Scandinavia, they sell for around $500 at auction prices.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 937)

Oops! We could not locate your form.