No Strings Attached

| September 12, 2023I was sure I could force a yes from Hashem if I proved myself worthy

Chapter 1

I looked up for a second to stretch and to rub the tiredness out of my eyes. The masechta I was learning was delving into one aggadeta after another — Yechezkel’s vision of the Merkavah and malachim rising and falling came and went from my mind interchangeably. I was finding it increasingly difficult to keep my focus. I need a chavrusa for this, I thought to myself lazily. Yet I knew that was a long shot. Who would be willing to learn with me this early in the morning at a fertility clinic?

When my wife and I were first married, we — like most young couples — didn’t give a second thought to any fertility complications. Even as the early months passed with “no news,” we just assumed it would happen eventually. Soon enough, we thought, soon enough.

But as the years passed and every new month met with dashed hopes, our worries began to grow. Our quiet nights and mornings, our peaceful Friday afternoons, and our uninterrupted Sundays had become deafening. Still, we put off considering any fertility treatment. Both fear and faith kept us on the natural path. Fear of invasive and painful medical procedures, and faith that our yeshuah lay purely in the spiritual.

Eventually, as the years continued to turn, the fear of the alternative became an aggressively bigger monster. And as for faith, well, this type of faith felt reserved for those much more pious. Many people with kind hearts but indelicate minds would compare our struggle to that of our Avos and Imahos. But I was under no such delusion that I could stand where they stood. I was purging constant shortcomings every Elul, and the comparison of my situation with the Avos started and stopped at infertility. No, we knew that it was time we turn to the bleak world of hishtadlus.

I sat hunched over my Gemara in another waiting room. My wife had just texted me that she was called back to see the doctor. The past tests had showed nothing conclusive about our situation, so that left us with attempting to throw everything at the wall to see what sticks. I felt my mind begin to cloud as the text on the daf blurred.

Since we began treatment at the height of Covid, I was not allowed into the actual clinic. Instead, I had to wait in the lobby — a largely empty space with tall ceilings and windows and a few armchairs. The paint on the walls was bland, and the art wasn’t adding much warmth or security either. A perfect place for an overactive mind to jump between despair and hope. Knowing my time was limited before my wife would return, I forced myself back into the amud.

I took this learning more seriously than I ever had before. With treatments looming just around the corner, it seemed so unfair that all of it would fall on my wife. I figured that besides just being a support system for her, I could also attempt to beseech G-d through my learning while my wife was attempting to have Him abide by the rules of teva He created.

My wife loved the idea. Even though I was painfully aware of how little the actual burden of treatment was on me, the fact that she was inspired by my learning seder helped me believe I was giving more than I actually could.

I felt like we were synchronizing, like this was exactly what Hashem wanted from me. The belief of an earnest fool. I just knew that the siyum I would make for this masechta would coincide with wonderful news. So the seder became much more than a seder about the text on the page. It was a seder about faith. I was sure I could force a yes from Hashem if I proved myself worthy.

Chapter 2

Faith is tricky. It often blossoms in soil not really fit for it. As a teenager, I would often marvel at the faith of those Yidden who lived through pogroms and horrible massacres. I revered their tenacity in holding on to their faith. I was in pure awe of their unwavering dedication in a world that seemed so indifferent to their suffering. And as a naïve teenager, I believed I could rise up to such a challenge as well. In fact, I often thought my faith was lacking because there was no such struggle to strengthen it. What I never considered was the fact that suffering doesn’t necessarily have an end date. And those who wouldn’t compromise on their faith did not do so to force salvation.

I thought if I really believed, if I poured out my heart to Hashem and became vigilant that my actions matched His desires, I would see deliverance. But we are not commanded to have faith because it saves us. We are commanded to have faith because it is right. Can anyone fathom that level of devotion? Could I?

My wife, who would have made our ancestors proud, certainly could. She would sometimes say, albeit through tears, that sometimes G-d says no. He does what is best and we must believe that, because we never see the whole picture. If not having children is what is supposed to happen, it will ultimately be in our benefit and in the benefit for the grand design.

She wasn’t happy to impart this wisdom, but she saw that as a flaw in herself, not in her Creator. It was never even a question that G-d would act for our total and complete wellbeing. But I was stuck in a narrower place. I admit that deep down, I couldn’t reconcile His love for us and His still-incessant refusal to mend our heartbreak.

Early on, we had set off on a path of spiritual betterment. Our Sages say to look inward when facing trials, to meditate on what we could do better. Through this process one would hope to see yeshuos.

We heard from one mekubal to learn in detail hilchos Shabbos, so every night before bed, we had our couple chavrusashaft. We heard from another mekubal that we should give tzedakah matching the exact amount of the infertility procedures, and so we happily emptied our wallets. On and on it went. Some of the advice was practical, some more obscure: eating certain foods, sleeping with certain objects near our bed, putting certain names under our menorah, lighting Shabbos candles with olive oil.

Privately, my personal betterment list became numerous. I rectified how I was saying Bircas Hamazon. I made sure to check every day that my tzitzis were kosher. I worked on countless bein adam l’chaveiro failings. I was hoping that starting these maintenance projects with the sincerity to continue them ad infinitum would be enough to allow G-d to turn the Heavenly key for children.

I sat in a different armchair this time in order to mix up the tedium. The appointments were becoming mainstays of our routine, this most recent series coming along with an additional process of home monitoring and treatment. This particular appointment revolved around one of the less painful procedures one can attempt for infertility, and our doctor recommended that we try these easier methods a few times before discussing the scarier options. I had escorted my wife up to the office, and then began my seder with a new sense of vigor. This is it, I thought. This is where the spiritual and the physical join and allow us to start a family.

My hope was at an all-time high as I delved deep into the sugya. We had worked so hard on our ruchniyus these past years; I was sure Hashem just needed a dedicated show of hishtadlus before He would answer our prayers. There is no way we would need to do any of those terrifying procedures.

Several months later, I’m back in the waiting room. They replaced one of the art pieces with a mirror. You would think it might give the room less of a sterile feeling, since waiting room art tends to the stale and pointless. Yet somehow the mirror makes the room even more depressing.

I flip through the remaining pages in my Gemara, and as I’m nearing the end of the masechta, it begins to dawn on me that my faith is attached to the pages. As the dapim dwindle, will my emunah as well? My progress in the sugya proceeds at a snail’s pace, afraid of the answer.

Absently staring into the new mirror, my mind leaves the most recent Talmudic dispute behind. I’m so confused. Does G-d need me to become the next gadol hador before I’m able to have a child? It feels like I’m trying to run up a hill in deep mud. Every apparent victory seems to conceal yet another trial.

Chapter 3

T

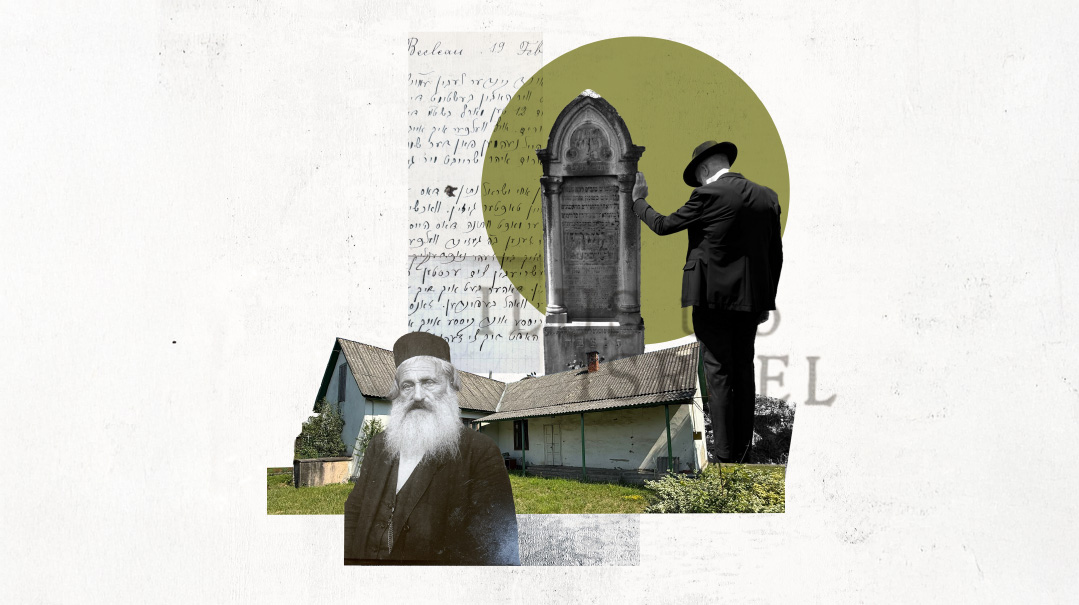

he months of waiting rooms and desperate prayers eventually came to an end. Our doctor advised us that we should stop the infertility processes we were currently doing and move on to the more invasive treatment option. But my battered faith, and my wife’s emotional and physical wellbeing, necessitated that we take a break. Both of us felt that before we moved on, we were going to get as much spiritual help as we could. And on to Eretz Yisrael we went.

We arrived in Eretz Yisrael right before Chanukah with the plan to stay there for the duration of the miraculous week. Between pouring out our hearts at holy sites and getting brachos and segulos face to face, we felt sure this step would work. We were in the Holy Land, a place where miracles came from. I felt tangible hope again.

For the entire week of Chanukah, we spent our time davening and visiting gedolim and mekubalim. I was ecstatic when they would point to a middah that needed fixing. At least that meant that there were options. At least that meant there was a stone unturned. Some told us we didn’t need to worry about starting the scary procedures, as they assured us it would happen naturally. Some told us we would have a baby within the year, a prospect that made our bruised hearts swell with joy. And because it is human to cling to hope, our Chanukah was full of simchah and reassurance.

When we came back to America, we immediately put all the segulos into motion and doubled down on the middos we were told to focus on. We told our doctor that we were going to wait a while before moving on to the next step. And we hoped that step would never come. This time it felt actually within our grasp.

But within due time, the year that we were promised was coming to a close and the answer was still no.

People never talk about the other side of segulos, when you’re standing after the promised time and trying to internalize all the practices you tried for the last year. When all the seemingly peculiar customs you attempted yielded nothing. My wife and I were never such segulah people before this, but desperation can make believers out of the skeptical. And now that the promises and brachos have not been fulfilled, what happens to my faith?

First, I let that old Jewish tradition of Yiddishe guilt kick in. Did I somehow anger Hashem so much that He revoked the time limit? I spent time scouring and analyzing the minutiae of every mitzvah, every segulah, that I did for the sake of children. But even if I found a centimeter out of place, would I truly believe that G-d was holding that up against all of our triumphs? Maybe if I were more righteous. But Hashem knows his customers.

After that comes a trial in faith. Did our actions make a difference? It would have been easy to keep believing in the segulos if there were no time frame given. Then we could keep believing that the amalgamation of segulos, mitzvos, and hishtadlus were continuously working behind the scenes. But when a holy person gives you a time frame and your wish isn’t fulfilled, what do you do after nothing “worked”?

At every interval of this whole process, I was worried about the breaking point of my emunah. But even with promises broken, I was surprised to find the well of faith had undeniably not run dry. My wife, ever the gibborah, lent me strength when I felt sapped of it. And I, ever indebted to her, offered up the platitudes I had heard in many shiurim, even when they rang hollow. So, we did what Yidden do. We comforted each other and found purpose there. And even when we felt betrayed by those who gave brachos and hurt that Hashem would allow our loved one to suffer so much pain, we still found reserves of faith.

Those were the dark months. While we prepped for the next procedure, we kept working on all the spiritual initiatives we’d take on, but at some level, we felt cast out. We didn’t feel that we were holy enough for this trial, and we didn’t feel that we were wicked enough for this suffering.

Soon enough, the painful and invasive procedures began. Team morale was at an all-time low. There wasn’t much time for hope, given all the appointments and medical prepping that needed to be done. Still, at every appointment, my Gemara tagged along. I would force myself into the daf, although my heart was rarely in it. Still, it was one of the only ways I could ward off the creeping resentment. Honestly, it felt like Hashem had picked the wrong soldier for this battle.

Chapter 4

IT

was the appointment for the big procedure, and again I found myself in a waiting room. Different from the ones before, this one had stiff wooden chairs around small square tables, with a television in the corner blaring the news, and my reliable companion — more sterile and boring art. With both my Gemara and Tehillim in hand, my plan that day was to daven during the length of the actual procedure and then to learn during the recovery time. Even after all those years of tefillos that seemed to have missed the mark, I still prayed my own private Neilah, banging on the doors of Shamayim.

After the fixed time for the procedure had finished, I paused. Slowly coming down from the heat of passion, I felt a cold fear grip me. The question of my faith returned. But this time the scenario was vastly more dire. If chas v’shalom this doesn’t work, and if chas v’shalom nothing works, how badly will my spirituality suffer? Will I be able to get back up?

The answer hit me with force and clarity: Despite all our heartbreak, and even in the face of my bitterness, my faith will remain. Jewish history contains reservoirs of pure faith. Our grandparents and the generations preceding them for millennia scrounged for faith like scraps of bread in a besieged city. Neshamos upon neshamos have clung to their faith, not as a tool, but as a purpose within itself. Should I need to borrow from them, I will.

It was in Kislev, the month of miracles, when we finally got the most beautiful news ever. The medical procedure had worked. I need not go into detail about our joy. There are special moments that transcend description, and no words can do it proper justice. Plus, some memories are too precious to share.

Of course, we were extremely thankful as well. Thankful to the Borei Olam for finally trusting us with this wonderful gift. And thankful that the pain would finally end after all these years.

But my relationship with Hashem didn’t immediately fall back on track. I found that when I would daven, there was a hinderance in my gratefulness. I couldn’t shake this feeling that Hashem didn’t want to answer us in the affirmative, but we forced His hand. I felt like a child who begged and begged his parent for a gift, only for the parent to concede because the tantrum wasn’t worth the effort. The procedures my wife underwent had potential serious side-effects. It almost felt like threatening self-harm in order to get what we wanted; like, despite all the tefillos and brachos, it was only when we put ourselves in a makom sakanah that Hashem conceded.

This feeling plagued me constantly and came with its own new set of doubts. Maybe Hashem knew something I didn’t about my ability to be a father. Maybe He wouldn’t go out of His way to inhibit us, but He wasn’t exactly thrilled with the idea either. When I brought up these feelings to my wife, she wisely disagreed. She reinforced for me that one can never know what a brachah or a mitzvah is worth, and you try everything, since you never know which one will end up being the catalyst for the blessing. She would often remind me that it was also a miracle that these procedures worked at all. Although I was heartened by her reassurances and her logic made sense, I still felt a spiritual distance.

Slowly, throughout the months of pregnancy, I felt the relationship begin to repair itself. It wasn’t some “Eureka” moment or an inspiring shiur in emunah. Instead, I began to notice how everything we went through changed us. Our lives felt full of purpose and mitzvos, and our marriage felt truly blessed. We came to understand that faith was not there to be a deliverance from the pain, but rather a framework in which your pain means something. A Yid does not trust Hashem because it will net him what he wants. A Yid believes because he understands he is part of something greater. We had made it through, and unequivocally we had become better from it.

Chapter 5

A

nother waiting room, but this one feels different. The chairs are just slightly comfier, the paint on the walls is bit more vibrant, and the art has a little more depth. Most importantly, in this one I get to wait along with my wife. I’m still clutching the Gemara under my arm, and although I knew I’d be too excited to actually learn anything, it felt wrong not to bring it with me, particularly on this appointment.

Before long, we are escorted into one of the back rooms. I utter a quick prayer of thanks and hope under my breath. Remember this feeling, I think to myself. Stash it in your emunah reserves. The image of our baby appears out of the static and comes pulsating onto the ultrasound screen. I turn to my wife, both of us in tears.

Our child should never know the devastation and anguish that led to this moment. Our child should not be burdened with the intricacies of our journey. But she will face her own challenges. And she will know emunah. She will know that faith doesn’t come with strings attached.

A few months later, and I’m waiting again. Waiting for the crowded room of family and friends to quiet down. My wife sits to my left, cradling our beautiful baby girl who sleeps peacefully, oblivious to the tumult around her. And my Gemara Chagigah is there too, open to the last page. The page that for a while there I was dreading to reach, but that now faces me with a comforting finality. Already fighting back tears of gratitude, I begin the siyum.

The last lines in Chagigah discuss the inner Mizbeiach. How the top of the Mizbeiach was covered with a thin layer of gold, yet miraculously, all the fire that burned upon it didn’t mar the gold whatsoever. And right there, I knew — that after everything we went through, after all my doubts and questions and inner struggles — as I said the Hadran Alach, I wasn’t marred at all.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 978)

Oops! We could not locate your form.