No Jew Left Behind

| August 15, 2023For brothers Rabbi Manis Friedman and Avraham Fried, it’s always been about the message they imbibed growing up

Photos: Itzik Roitman

It’s that time of year when we begin to re-examine our lives, taking stock of the past and hoping to move forward to a future using the talents and opportunities we’ve been gifted. For two of the Jewish world’s most famous brothers — Rabbi Menachem Manis Hakohein Friedman and Reb Avraham Shabsai Hakohein Friedman, a.k.a. Rabbi Manis Friedman and Avraham Fried — having an impact on hundreds of thousands of Jews around the world has meant harnessing those gifts, each in his own way. While one is a venerated kiruv personality and chassidic educator and the other a king of Jewish music for four decades, it’s all about the unswerving messages of mission with which they were imbued growing up.

Although there are 13 years and a bit of a generation gap between them, you can’t miss the mutual admiration and farginning, as they’ve come together for a nostalgic interview to reflect on the place where it all began, the home in which they grew up, their successes and failures, and to try to answer the question: How to stay focused on the bigger picture, on humility and on your shlichus, in the shadow of so much hype and fame?

For them one thing is clear: More than they chose their professions, the professions chose them: “I think that at the end of the day, each of us sees ourself as an emissary of HaKadosh Baruch Hu,” says Fried.

We sit together in Rabbi Manis Friedman’s modest Crown Heights living room, a few blocks away from his brother Avraham Fried’s home. For Reb Manis, being back in Brooklyn still takes some getting used to — for close to five decades he carved out his niche in Minneapolis, Minnesota as director of the Beis Chana Women’s Kiruv Institute, as a world-class lecturer and even the disembodied voice of “Tanya in English” on international call numbers (although the younger generation mostly knows him as “YouTube’s most popular rabbi” for his abundance of online lectures and seminars).

“We grew up in a home of mesirus nefesh,” says Reb Manis, noting that the roots of Jewish activism have been in the family for generations. “Our grandfather, Rav Meir Yisroel Isser Friedman, was the rav of Krynica, or Krenitz, a vacation spot in western Galicia that was frequented by many of the pre-World War II gedolim. He was close to the Sanzer and Bluzhever Rebbes, and his children — including our father, Reb Yaakov Moshe — grew up in the presence of the rebbes and gedolei Yisrael who came to Krenitz in the summer months. One of them was the Kedushas Tzion of Bobov Hy”d, and our father attended the yeshivah he established in the city.”

“When they were children,” says Avremel, “they had a special rotation to wave a fan whenever the Kedushas Tzion would lie down to rest, so that the flies wouldn’t disturb his sleep.”

The onset of the war forced the Friedman family into exile, first into Siberia, then into Tashkent, Uzbekistan. The teenage Yaakov Moshe — or Yankel, as he was called — worked a double shift to spare both himself and his father, the Krenitzer Rav, from having to work on Shabbos.

Yankel dedicated himself to the many refugees who’d also fled east. In one instance, he walked more than 30 kilometers in tattered shoes to bring food to a starving widow and her seven young children, fighting off wild dogs on the way.

It wasn’t long before the energetic, dedicated Yaakov Moshe was noticed by Rav Yosef Baruch Reichverger and his rebbetzin, fellow refugees from the Ukrainian town of Kuzmyn. He’d been declared a “parasite” for the crime of being a rabbi, and after surviving an arrest, his family too fled east. Yaakov Moshe married Miriam Reichverger in 1944, and their first child, a daughter, was born the following year.

When the war ended, Yaakov Moshe arranged passage for his father and siblings to America, but he and his young wife accepted an invitation to assist the legendary Dr. Jacob Griffel of the Vaad Hatzalah in helping stranded survivors who’d made their way to Prague.

Reb Manis was born in Prague in 1946, as his parents threw themselves into dangerous rescue work that involved forging entry visas, smuggling refugees across borders, and paying off all sorts of government officials. Yaakov Moshe established particularly good connections with the Guatemalan and San Salvadorian consulates, and through them managed to secure visas for thousands of refugees.

With the Communist takeover of Czechoslovakia in 1948, the authorities caught up with the couple’s activities, and Yaakov Moshe was arrested and tortured, leaving Miriam to care for three young children — although before his six-month prison sentence, he managed to transfer an entire orphanage of Jewish children to Vienna, where suitable arrangements were made for each child to travel to Eretz Yisrael.

Family in the United States raised money for his release, and with the blessings and financial assistance of Rebbe Yosef Yitzchak Schneerson of Lubavitch, Yaakov Moshe was freed from prison, and able to obtain exit papers for himself and his family.

They made their way to the United States in 1950 and settled in Crown Heights, where Yaakov Moshe got a job working in the administration of the United Lubavitcher Yeshiva, a position he would hold for 40 years.

“My father would go to the bank each morning for the yeshivah, and he made sure to use those errands to help others — cashing their checks, guaranteeing small loans, helping with paperwork,” Avremel says. “There were lots of survivors who needed help with the basics, and his patience and willingness to assist put so many of them back on their feet. The tellers would joke that the line for Rabbi Friedman was the longest in the bank.”

The Friedman children — six boys and two girls (Avremel is the youngest) — were sent to Lubavitcher educational institutions and each of them became Lubavitcher chassidim, yet that sense of mission that all the children were imbued with and eventually fulfilled in their various life choices were apparently deeply rooted before Chabad shlichus came into being.

“Indeed, those roots were always there,” Reb Manis affirms. “But the Rebbe gave us the tools to leverage that desire to much broader horizons, so that they could influence the whole world, not only our immediate surroundings.”

While the Zeideh, the Krenitzer Rav, lived in Boro Park and had a harder time coming to terms with the “defection,” Avremel explains that, “Although our father remained a Bluzhever chassid and was close to Bobov, he gave all eight of us as a gift to the Rebbe. In the end, he had great nachas seeing his children and their families becoming talmidei chachamim, rabbanim, and shluchim. Two daughters in Detroit and Long Beach, California, Manis in Minneapolis, a brother in Kansas City, one in Tzfas, one headed Lubavitch Youth Organization in Crown Heights and another Kehos Pulbishing — and then there’s me. I’m just a singer….”

“You’re the biggest shaliach of all — we’re all trying to follow in your footsteps,” Reb Manis exclaims, coming to his younger brother’s defense. “Your insistence on using every performance to share divrei Torah, to give tzedakah in public and to share hope and inspiration, makes you one of the shluchim with the widest reach.”

Avremel gives back the compliment. “I don’t know if you know,” he says, “but my brother Reb Manis is my source of inspiration. He was the very first rav to take out tapes of shiurim on chassidus. It all began with him.”

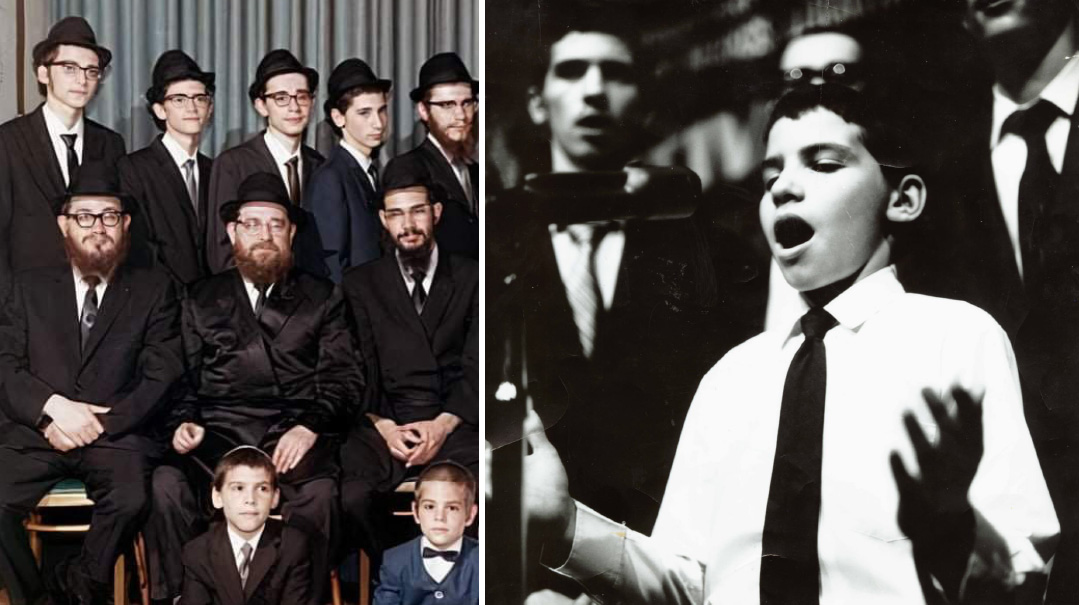

The Friedman family left a legacy of mesirus nefesh. (Left) at the wedding of their oldest sister; (Right) a young Avremel Friedman, who brought the house down with his sweet voice

Manis and Avremel — the oldest and youngest brothers — not only grew up in a different world from their parents, but essentially grew up in different worlds themselves.

“Well, I barely remember Prague,” says Reb Manis, “but even once we arrived in the US, we were living in survival mode. We were just trying to stay afloat with our Yiddishkeit. By the 1980s Yiddishkeit was a fashion, kiruv was a fashion, and putting out a record was accepted. Music was a very appropriate tool to harness all that spiritual energy in the world. And then, by the time my son Benny got into it, there was internet, and you could become famous overnight.”

Avremel might say he’s “just the singer,” but today it seems that the entire Friedman clan is getting in on the action — his nephews Benny Friedman, the Marcus brothers, and even Simcha Friedman from Tzfas are doing their own kind of shlichus through music. (Reb Manis hasn’t missed out either. He’s got a cameo appearance on his son Benny’s “Charosho” video, his ever-smiling, cheerful countenance a happy backdrop to that popular song of gratitude.)

In 1971, as a newly-minted rabbi and a newlywed, Rabbi Friedman and his young family were sent on shlichus to the Twin Cities in Minnesota, and decided to invite female college students from campuses all over the US for a summer session of Torah learning.

“At the time we had two kiruv yeshivos for men,” he says, “one in New York, and one in Kfar Chabad. One night I was sitting around with Rabbi Moshe Feller, the first shaliach to the Midwest and we started joking, ‘Great, we’ve created all these baalei teshuvah, but who are these guys going to marry?’ It started as a joke, but it was a very serious question.”

Rabbi Friedman wasn’t sure if it was appropriate for a 25-year-old chassid to teach women, so he improvised with a group of 16-year-old girls from Crown Heights who’d come to St. Paul to help with the summer day camp. In this rather makeshift way, Bais Chana was created, headed by Rabbi Friedman and Rabbi Feller with his wife Mindel a”h, a first spark that would be a precursor to women’s kiruv seminaries in the US and Eretz Yisrael.

“In our short program, we would only get the women to the first rung, getting them interested in learning more,” he says. “It was 1971, America was still stuck in the Vietnam War, and these were politically-savvy young women who came in demanding to know what Judaism had to say about the war and fixing the world.”

The following year, though, things had changed. The war was over, and instead of fighting, these women were into meditation and eastern religions. Now they wanted to know what Judaism has that Buddhism doesn’t.

Word began to spread, and soon Bais Chana was offering several outreach sessions a year. In the over five decades since its inception, Rabbi Friedman estimates he merited to teach over 30,000 women.

“Those were years of great awakening,” he says. “It was an independent generation that was ready for drastic changes.”

Today, Rabbi Friedman is no longer in Minneapolis (he moved back to Crown Heights during Covid, as an “experiment,” and is still there), and neither is Bais Chana.

“But I didn’t leave, and I didn’t retire,” says the rabbi who will be 80 in three years. “Beis Chana grew to where it was just no longer practical for everyone to come to Minnesota. Today we run 15 sessions a year all over the country for various specialized groups based on age and life situations. So really, Bais Chana is everywhere.”

Still, a lot has changed since the kiruv energy of the ‘70s and ‘80s. “It’s actually been a very profound change,” says Rabbi Friedman. “Forty years ago, Yiddishkeit was novel and people got so excited about it and inspired that they’d drop out of their previous lives and go off to an oasis of Torah in Neve or Aish. Over the years, what changed was that Yiddishkeit sort of became mainstream. Today, it’s just not the style to drop out of life to go off to yeshivah in order to be a baal teshuvah. Instead, you incorporate Yiddishkeit into the life you’re living. You don’t have the drama of the upheaval, it’s not so exotic — instead it’s become integrated in a more natural way. Today’s baalei teshuvah don’t even realize how much they’re changing and don’t even call themselves baalei teshuvah. They’re just putting on tefillin and keeping Shabbos and kosher and sending their kids to Jewish schools. It’s just moving into a new norm.”

Does that mean that in his personal shlichus, iconic kiruv personality Manis Friedman has shifted from the “BT drama” to “FFB kiruv kerovim, especially given his huge following in the frum world through his online lectures and podcasts?

“You know, half my audience is frum, and another chunk isn’t even Jewish. I have no idea who they are, but all of them are listening to the same ideas. It’s really how Torah and Yiddishkeit have become universal,” he says. “I don’t dilute anything. I give over the emes without worrying about being politically correct. On the contrary, if you want to reach more people, you have to go deeper, not water things down. The problem is that people today don’t trust their own judgment — we’re a coddled, apologetic generation because we’re so insecure about what is true, and the only way to fix it is with emes.”

Today, Rabbi Friedman has become somewhat of a guru for relationships and shalom bayis. “It’s a direct outgrowth of Bais Chana,” he says. “I’ve been speaking to women about this topic for the last 52 years, where the hottest subject is family. Relationships. Marriage, kids, parenthood. People are in crisis over these things, because all the rules have fallen away.”

The main rule that will restore happiness and harmony to Jewish homes (and really, to all families around the world)?

“Couples are unhappy today because there’s a certain paradigm that Hashem put into the world, that men are wired to be mashpiim (givers) and women to be mekabel (receivers),” Rabbi Friedman explains, “and if that structure doesn’t exist on a deep level, then they’ll be miserable, no matter how much money they have or how happy their opulent physical surroundings are supposed to make them.”

How did it fall apart? Did the men stop being the givers, or did the women stop being the receivers? “I’m not sure where it started,” he says. “But one thing is clear: Building a career is an activity, not an identity. When a woman comes home, her natural inner desire — no matter how politically incorrect this sounds — is to be able to lean and rely on her husband on a deep emotional level. But it could be he’s abdicated being the mashpia, and then she gets frustrated. She becomes the CEO at home as well, he becomes arrogant instead of giving, and they’re both unhappy. The only way a man and a woman can live together under the same roof is if he’s the giver and she’s the receiver. Otherwise, they don’t need each other, and it’s a very big loss, on both sides.

Today Rabbi Friedman uses media to get his messages across, but says the seeds of that were planted much earlier.

“In the 1980s, when I was a simultaneous translator on live broadcasts of the Rebbe’s farbrengens that were aired all over the world, I began to understand the immense power of visual media to disseminate Jewish content.”

A younger Manis Friedman, who was one of the first to harness technology for the dissemination of chassidic teachings

Last Lag B’omer marked 40 years since Avraham Fried’s first album, No Jew Will Be Left Behind. But what makes a yeshivah bochur in the prime of those years decide to become a singer and to even produce a recording?

“The truth is that this sense of shlichus began when I was a little boy,” says Avremel. “We were neighbors of Rebbetzin Chana a”h, the Rebbe’s mother, a truly remarkable woman. With mesirus nefesh, she traveled with her husband, Rav Levi Yitzchak ztz”l, the Rav of Dnipropetrovsk, when he was exiled to Kazakhstan for the crime of disseminating Judaism. When she was finally reunited with the Rebbe after not seeing him for several decades, she became our neighbor on President Street, and would listen to the zemiros on Shabbos and Yom Tov from our house, as my father was strict to sing them according to the nusach he received from his father. That brought her great joy, to the extent that she even told the Rebbe about it.

“From time to time, she’d ask my mother to bring me over to sing for her. That’s how, when I was just four, I sang for the Rebbetzin and made her happy — one time she gave me a quarter, which was a fortune then, and I ran to the toy store and bought a water gun. The gun broke right away, but I think that awareness, that I had the ability to make people happy, influenced how I saw myself.

“People ask me if I ever sang for the Rebbe. I don’t know if the Rebbe ever heard me sing, but I remember how the Rebbe visited his mother every single day, no matter what. We, who knew the exact hour of his visit, would stand by the window, and when he would pass, we would knock and wave, and he would wave back. Sometimes we’d wait outside, and when the Rebbe passed, I remember how I once sang for him and how he encouraged me with his hand.”

Avremel first sang for an audience when Eli Lipsker, of Nichoach (Niggunei Chassidei Chabad) fame, created a children’s choir that would travel around the country giving exposure to Chabad.

“He would coordinate with the local shaliach, who would host an evening of Torah and song,” Avremel says. “It was a really special experience to be part of spreading chassidus, even at that age.”

Later, Avremel joined Rabbi Eli Teitelbaum on the Camp Sdei Chemed and Pirchei Agudah recordings. “I had this really nice solo he gave me, the high part of ‘Hakshiva el Rinasi,’ and the day we were supposed to record, my voice changed. I came to the studio croaking. Reb Eli understood right away that I would be devastated, so, nice guy that he was, he asked me to switch to the low part so that I wouldn’t feel bad.”

After his bar mitzvah, Avremel put singing on the back burner. He learned in the Lubavitcher yeshivah system, first in New Haven and later in Oholei Torah, back in Crown Heights.

“I was about 20 years old and ocassionally singing on various recordings,” he says. [His first two were “Aruka Me’eretz Middah,” composed by Suki Berry for the Amudei Sheish Wedding Album, and “V’hu K’chassan” on Suki with a Touch of Ding.] “I felt pulled to do something, a certain stirring deep within myself.”

Avremel notes that the music they grew up with was beautiful, haunting, and moving, but the messages — ani ma’amin, tears, emunah — were fundamental but not very freilich, more about strengthening emunah and moving on. Avremel had a plan, though — an idea about bringing out music that reflected optimism and real, tangible hope for Geulah. He didn’t tell anyone about it, but he wrote a letter to the Rebbe explaining his idea, and the Rebbe wrote back wishing him hatzlachah — and instructing him to print the words, “Please do not play this recording on Shabbos and Jewish holidays” on the album.

“It seemed like a strange suggestion,” Avremel says. “I mean, how many people were there who were into chassidic music but not into Shabbos?”

One Shabbos at a farbrengen, the Rebbe made a comment that “No Jew will be left behind,” and that was the message he wanted to share. Avremel felt that younger audiences would appreciate the rousing music and message, and believed at the time that he himself could remain anonymous. “If I shortened my name to Fried,” he says, “I figured no one would make the connection.”

Before long, though, the secret was out. Wedding and concert invitations began piling up — and what about all the challenges that come with fame and popularity? “Looking back, I had siyata d’Shmaya. I guess that I felt an achrayus, a responsibility to the Rebbe and the chassidus, to be a good representative.”

Maybe it has to do with what his wife, Mrs. Tzivia Friedman, told Yisroel Besser in a Mishpacha interview ten years ago, right after a HASC concert: “We’re quiet people. Music is wonderful, but not who we are. My children aren’t here tonight. My husband says that boys belong in yeshivah, there’s no reason for them to come. We’re very proud of our Tatty, but we’re a regular family.”

Avremel says that all his Enlgish songs are based on the words and ideas the Rebbe shared at farbrengens, and “No Jew Will Be Left Behind” set the tone early on.

“By the way, the copyright to that song is really mine,” Reb Manis comments.

“Really?” Avremel asks. “After so many years, I start to forget.”

“Yeah, the inspiration came following a story that I told you,” Reb Manis clarifies. “One day, I was riding the subway and as I was getting off, I met a not-yet-religious Jew I knew. I started giving him a few quick words of chizuk, although his second foot was already about to board the train. I realized that I didn’t have much time, so I told him the following: ‘Even if you’re not interested, know that we need you, because Mashiach won’t be able to come without taking every Jew with him, so without you, no one else goes.’ When I told you about it, you said you wanted to make a song about it.”

“There, you have a scoop,” Avremel says, patting his brother on the back.

Little Avremel would bring joy to the Rebbe’s mother, their neighbor, by singing for her. She even shared with the Rebbe how happy it made her

Avraham Fried is a rare phenomenon — a Yid who, for four decades, has undisputed control over the soundtrack of our lives. His vibrancy hasn’t faded, and he is still invited to perform all over the world.

Despite all that, anyone who knows him personally knows that they’ll be met with a captivating smile and no airs — a role model for how not to let fame and glory get to one’s head. Perhaps that’s part of why he has an uncanny gift for connecting to his audiences.

“I try my best to get a sense of what they’re looking for,” he says. “Sometimes you can feel it in the air. It’s the time of year, or type of community, and other times you have to work harder to connect, to give the people an experience that goes beyond the music. If I’m davening, I want them to daven with me. If I’m happy, I want them to feel happy.”

Avremel admits that there are a few approaches to how to become a singer. Some do it for parnassah, others for the “star” factor. And still others view it as a mission.

“When I began to get involved in music, I really didn’t want the glory or publicity. Then, at the first siyum of the Rambam in Eretz Yisrael, the organizers reached out to the Rebbe and asked for his consent to invite me to an exclusive performance. Because the Rebbe gave his agreement, I was convinced that there is a dimension of shlichus here, and that’s when I began.

“I don’t deny that the stage has an effect on the ego,” he contines. “So that’s why I try to constantly tell myself that HaKadosh Baruch Hu has granted me an opportunity to arouse people, to help make people happy, and mostly, to influence them to be better through the divrei Torah that I customarily share while onstage. It’s my job, and it isn’t different from the job of every other Jew.

“But just between us, when I sit here next to my brother Reb Manis, a Jew who has brought so many thousands of Yidden back to teshuvah, what do I have to be boastful about?”

There is a certain trend in chassidic or modern frum music that more and more artists are abandoning modern music and starting to refresh ancient chassidic niggunim. Is there really a return to authentic Jewish music, or is it another passing fad?

“I really hope that it’s coming from a recognition that chassidic music is something pure and holy,” Avremel says. “Sometimes we’re tempted to look in foreign places, but the soul yearns for the source. It’s a cycle that goes around. A new generation has arisen that is yearning for authentic Jewish music. So finally, we’re returning back to the source.

“When I began recording Yiddishe Gems with the niggunim of Reb Yom Tov Ehrlich, on whose music we grew up, a lot of people told me, ‘Who is even interested? Yiddish is a small and disappearing market.’ And I said to them, ‘I’m doing it for my children. Anyone else who wishes to partake is invited.’

“The same thing happened when I began to make the Chabad albums. Lots of people said to me, who is going to listen? Maybe the Chabad people. But baruch Hashem, my greatest nachas today is when I come somewhere to sing and the first thing people ask me for is a good Chabad niggun.”

During the years where it appeared that music was going in a different direction, wasn’t the longtime singer afraid of becoming irrelevant?

“It’s always a thought, but because I see music as a mission, I know that there are lines I won’t cross, that’s not part of my shlichus. It’s out of bounds. Within the framework of authentic chassidic music there are a lot of styles that can be integrated that still preserve the music in a pure and unsullied state. And the truth is, I’m very strict about texts. People are always sending me new songs, but the thing that interests me most, from the outset, is the words and the message they’re conveying. Chizuk? Encouragement? Hope? Every song has to arouse a person, move him, and teach him something.

“Take for example the song “Ribon Ha’olamim.” I realized right away there was something special to it and I’m happy I had the zechus to record it. At the same time, I’ve learned over the years that every song has its address and that singer will have the zechus to move Yidden. It’s happened a few times that I was given a song and rejected it, and then I felt like I’d missed out.”

Although there are 13 years and a bit of a generation gap between them, you can’t miss the mutual admiration and fargining that characterize the relationship between Rabbi Manis Friedman and his brother Avremel

While both brothers — and the rest of their siblings — packed in the levels of mesirus nefesh they imbibed from their parents (although Reb Yaakov Moshe had a hard time wrapping his head around the fact that his youngest son had become a popular singer, telling him, “Ah zinger? What kind of girl will marry a zinger?”), Reb Manis gives comfort to parents whose children find a different direction for finding meaning in their lives.

“Today,” he says, “the only way to be Jewish is to be a baal teshuvah, in the sense that you have to make Yiddishkeit your own. You can’t inherit it from your parents, no matter how frum they are. Every yeshivah boy and girl has to ask themself, Is this who I am? Is this what I was created for? Is this what G-d needs from me?”

Rabbi Friedman says the biggest blessing he got out of Bais Chana was in the early days, when he was sitting in front of a room full of women, trying to convince them that Yiddishkeit is good for them, necessary for them, the right thing, their ticket to happiness.

One woman, very sweetly and nonconfrontationally, raised her hand and said, “Rabbi, all this stuff is very nice. But I don’t need it.”

“Now, you can become a salesman and convince them that life will be better for them if they keep Shabbos and have families, and you can try to convince them that they do need it,” Rabbi Friedman says, “but the bottom line is that they really don’t need it.

“Instead, it’s what’s needed from them.

“This is much deeper and goes way beyond their own perceived needs and preferences. One of the main questions I’d get asked was: ‘How could it be that it interests Hashem, the Almighty Who created the whole world, I if eat a piece of meat that was shechted this way or that way?’

“Because Hashem needs it from you. For Him, there’s no such thing as a ‘big’ mitzvah or a ‘small’ mitzvah. You know, today we’re not so connected, we don’t really know how mitzvos impact us. All we know now is what Hashem is asking of us. The irony is that while it’s the only level we have left today, because we can’t connect to the other levels, it’s really the highest level, because it means we’ve bypassed all the stages of the ego.

“But it’s not just what Hashem wants from you. He needs you, otherwise He wouldn’t have created you in the first place. This is a very beautiful and healing concept for a confused, disillusioned generation — and not only for Jews. It means that if Hashem put you in the world and you woke up this morning because He breathed life into you, He wants you around today. He gifted you with your unique set of talents, and He needs you to partner with Him in bringing light and redemption to the world, so that — as my brother says — no Jew will be left behind.”

Rachel Ginsberg contributed to this report.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 974)

Oops! We could not locate your form.