No Compromises

Visitors to Rav Aharon Leib’s apartment were struck by the incongruence between the bare-bones abode and its resident’s rich spiritual influence. But Rav Steinman saw it differently: All his life, he was preparing for a final accounting, and he allowed himself no compromises

Photos: Flash90, Mattis Goldberg, Mishpacha Archives

I

t was a daunting assignment for the secular journalist: Visit an elderly sage in Bnei Brak and decipher his unusual power to shape the policy of virtually all Israel’s chareidim.

The journalist followed his instructions. But on his visit to Rav Aharon Leib Steinman’s home, the puzzle grew only more difficult.

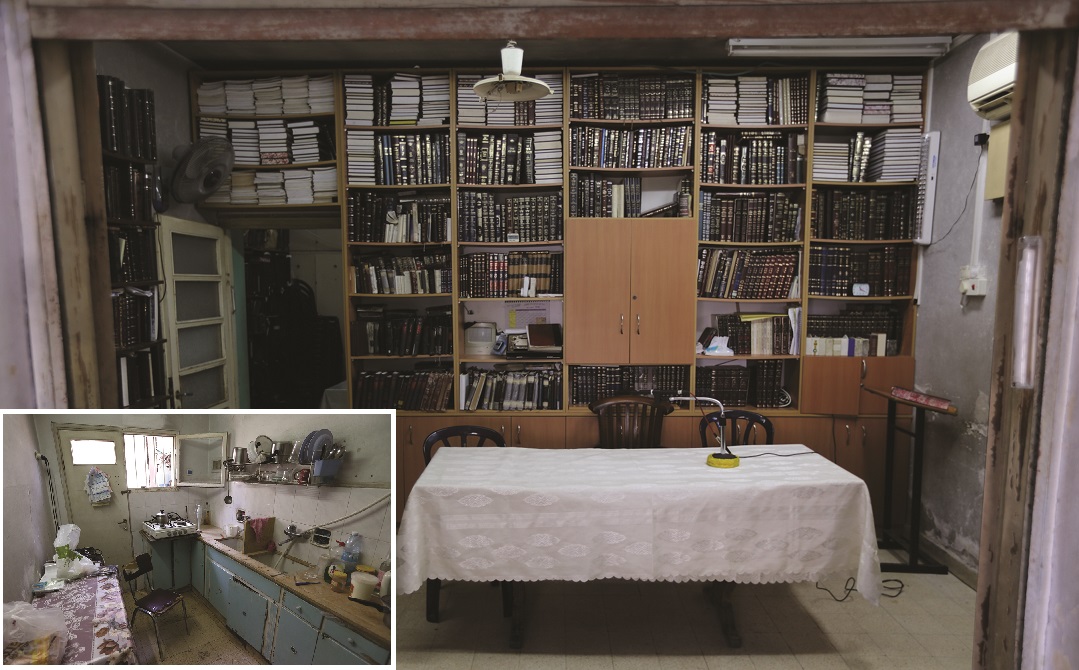

“The words ‘modest’ or ‘humble’ don’t do justice to the utter asceticism of the rabbi’s digs,” he wrote. “Entering the apartment is like a time warp to an Israel of 60 years ago, which is the length of time the rabbi had been living there…. There is no sign in the apartment entryway, on the mailbox or on the front door, announcing that you’ve arrived at the home of one of Israel’s most powerful men.”

He wouldn’t be the only person to note the incongruence between Rav Steinman’s bare-bones residence and rich spiritual influence. But his son Rav Moshe explained that Rav Steinman had a different view.

“Our father would tell us,” Rav Moshe says, “it says that a person has to be happy when he has yissurim, because then he fulfills his obligation for exile. ‘What do you care? Why don’t you fargin me to have exile in my own house? For galus I have to travel around the world?’

“There are people who talk about the way he survives on so little food — he’s been eating the same thing every day for the past 20 years,” Rav Moshe told Mishpacha’s Aryeh Ehrlich. “In fact, our father once said that he could never forget to say Retzei in the Shabbos bentshing, because the only time he washes and bentshes is on Shabbos. During the week he adds a little apple compote to his meager soup in order to boost his daily brachah count to the required 100 brachos.

“But he doesn’t see himself as deprived, not at all! Our father once told us, ‘In Russia there was a very wealthy Jew named Wissotzky. He had a big tea factory. He was a millionaire, and every day he ate expensive cuts of meat. Normal people could not allow themselves that luxury — they saved the meat for Shabbos. But Wissotzky ate meat every day, so how could he make his Shabbos fare special? He would eat compote. Imagine, Wissotzky the millionaire, allowing himself to eat compote only on Shabbos, while I eat compote every day. So am I deprived?’ ”

My Palace

Others might consider his home — with faded paint and trademark iron bedframe — spartan at best. But Rav Steinman was perfectly happy with the apartment on Rechov Chazon Ish, perhaps because he always had his eye on his eternal residence. Once, when discussing the Gemara that states that a talmid chacham needs to have a dirah na’eh, Rav Steinman exclaimed, “Like my dirah. I live in a palace!”

Once, just a few moments between those simple walls saved a couple’s shalom bayis. This couple came to Rav Steinman to discuss getting a divorce. The Rosh Yeshivah was busy with someone else, and after 20 minutes of waiting, the couple picked themselves up and walked out, telling the Rebbetzin, “It’s fine, we don’t need him anymore.”

What had happened? For many weeks prior, the couple had been making plans to renovate their home. The constant disagreements on how to go about it led to disputes, which spawned more strife and more dissent. Eventually they decided to divorce. “Being in this home and seeing how simply you live,” they told Rebbetzin Steinman, “we realized that our reason for divorcing is silly.”

It may have had bare furnishings and peeling paint, but Rav Steinman considered his apartment a palace

True Pain

A few years back Rav Moshe accompanied his father to the hospital for a painful gastro procedure, but Rav Steinman refused any kind of anesthesia. In the recovery room, Rav Steinman — satisfied that he had won the battle — admitted to his son that he was in pain, but shrugged it off.

“The procedure is usually done under general anesthesia, but our father insisted that he didn’t want it,” Rav Moshe said. “I asked why, and he replied that there is a possibility that general anesthesia can adversely affect one’s memory, and that is potentially a transgression of hishamer lecha pen tishkach es hadevarim. One is forbidden to forget words of Torah.

“I was with him in the room during the invasive procedure. It took about 20 minutes. All that time his face registered nothing, not even a twitch or flinch. Just total concentration. Later, I asked him if the doctors are lying when they say you need anesthesia for this. And he answered, ‘It all depends on a person’s pain threshold.’ I don’t believe this was a question of willpower, but rather the self-definition of the concept of pain. If my father had felt pain, it would have been apparent — something, a kvetch, a grimace. But because there wasn’t even a sigh, it meant that he had an entirely different concept of pain. He simply didn’t feel it.”

When did Rav Steinman express pain? “Only in spiritual matters,” his son said. “When he said he didn’t do teshuvah, or when he spoke of the Final Judgment. That’s when we’d hear him sigh.”

As Rav Steinman grew weaker, his grandchildren and great-grandchildren set up a night rotation so he wouldn’t be alone. Yonoson Honigsberg — a grandson of Rav Steinman’s son Rav Shraga (his father is Rav Shraga’s son-in-law Rav Gedalia Honigsberg) — slept in the Rosh Yeshivah’s apartment for many nights and was been privy to many of the thoughts and fears of a great talmid chacham making an accounting of his own long life.

According to his great-grandson, the Rosh Yeshivah (to whose learning most of us would aspire to just a fraction of) often sighed deeply about the pain he felt for every minute not fully maximized, about another masechta in Yerushalmi that he didn’t learn 101 times. Despite a century of tireless devotion to his learning and avodah, he never compromised on his personal spiritual standards.

“People think that the Yom Hadin is a distant, abstract thing,” he told his grandchildren after he reached the age of 100. “Being blessed with long life is not a simple matter. One who lives 70 years has to give a reckoning of 70 years. But one who lives 90 years will have to give a reckoning for all 90….”

He grew animated as he painted for them the scene he lived with every day. “A person will come on High and will be asked, ‘So, they say you’re a tzaddik?’ And I will be so embarrassed. Embarrassed before my father, because I didn’t turn out as he expected. How do people say in hespedim that someone is a tzaddik when he really wasn’t? In Heaven the niftar gets flogged for the misconception. I always say to write as little as possible on a matzeivah. People ask me why I don’t give hespedim and I say that I have compassion on the soul of the deceased person.”

Vidui Every Day

Shortly before his 100th Rosh Hashanah, it was as if Rav Steinman saw the Heavens themselves open up in harsh judgment, and his heart clenched in fear.

“How many Shasim are in the cupboard?” he asked his grandsons. Three, he was told, and another one on the table. “And how many Shulchan Aruchs?” he asked. To their surprise, he explained: “When I arrive in the World of Truth, they will tell me, ‘You had Shasim. Why didn’t you learn them?’ The Rambam will come and say to me, ‘You had all my seforim at home. Not one set. Two. Why didn’t you learn?’ I will be so ashamed.

“I was always afraid,” Rav Steinman revealed, “to buy seforim for no special reason, because I can’t have seforim on my shelf that are not in my head. I’m afraid of it. I had the privilege to be able to publish the sefer Ayeles Hashachar on Zevachim. When my personal Day of Judgment arrives, they will tell me, ‘You wrote a sefer on Zevachim. If you hadn’t compiled it, that would be one thing. But you did, so now repeat what it says in Gemara Zevachim….’ It will be so shameful for me.

“On the one hand, there’s an advantage to arichus yamim — one can do more mitzvos,” Rav Steinman continued, “but on the other hand, we will have to give a reckoning of every minute and second. I sometimes think to myself, what’s better for a person? To have a long life, and then have to give an accounting for every second, or to live a shorter life, and therefore give less of a reckoning on Judgment Day?”

Around Pesach time three years ago, Rav Steinman felt very unwell and began to recite Vidui. Then he found succor in the fact that those who depart This World in the month of Nissan are spared the pain of chibut hakever (torments of the grave). When this was repeated to his mechutan Rav Chaim Kanievsky, Rav Chaim replied with a smile: “I know Rav Steinman for many years. He’s probably been saying Vidui every day since his bar mitzvah….”

Well past the century mark, the Rosh Yeshivah never used his age to justify any halachic leniencies. The Rosh Hashanah minyan in his home would begin at 5:30 a.m. and finished by 8:30. The reason for the speed was the Rosh Yeshivah’s insistence on standing for the entire Shemoneh Esreh of the shaliach tzibbur, including the piyutim and the tekios. When the crowd insisted that the Rosh Yeshivah sit, his response was near-tearful: “HaKadosh Baruch Hu brought me to the age of 100 so that I should sit during the tekios?”

On Erev Yom Kippur, when his family tried to persuade him to accept an IV for hydration, Rav Steinman recoiled. “When I come to Shamayim, what will I say?” he cried. “I’ll tell them that I managed to fast for 99 years, and then decided I was exempt the next year?”

The Simplest Jew

Rav Steinman left several different versions of a last will. All were in keeping with his focus on the Next World and his disdain for material frills or the slightest speck of honor. This Tuesday morning, as they woke up to the shattering news, hundreds of thousands of bereft mourners from all around the country tried their best to make it to Bnei Brak for the levayah. Rav Steinman had insisted, however, that no hespedim be delivered and that the burial be completed within six hours of his passing, that he be treated as the simplest Jew, and that bittul Torah be minimized. In keeping with his ironclad priorities, the levayah was over before many had even arrived in Bnei Brak.

Even after he had left the world, his empty apartment — his “palace” — and his brief levayah, like that of the “simplest Jew,” echoed the singular spiritual focus that had motivated him for more than a century.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha Issue 689, Special Tribute Supplement)

Oops! We could not locate your form.