Nightmare Without End

Jon and Rachel Goldberg-Polin will do whatever it takes to get their son back alive

Photos: Elchanan Kotler, Goldberg-Polin Family

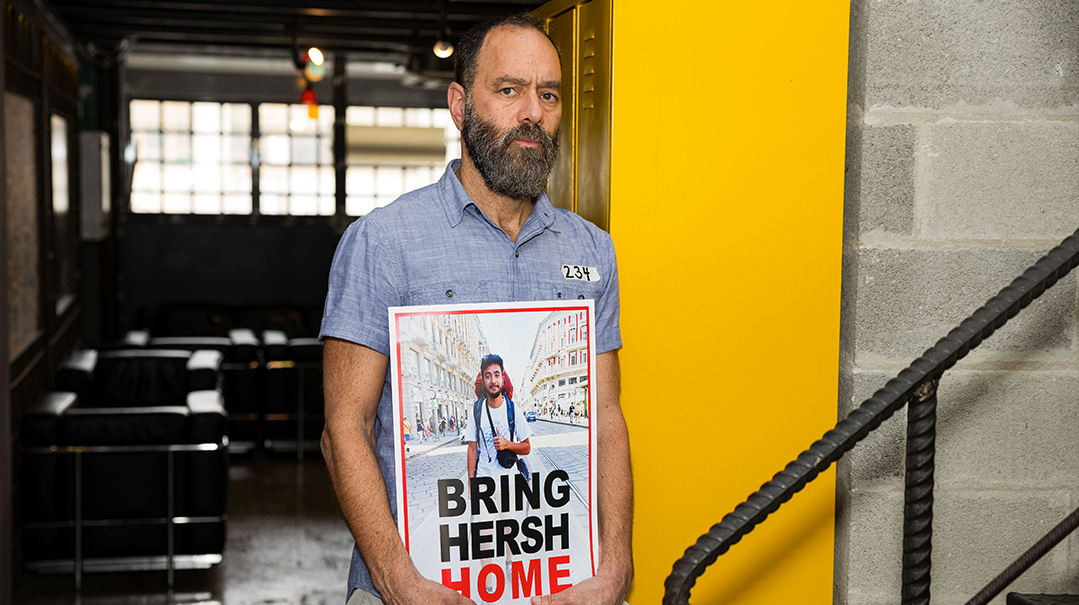

When their grievously wounded son Hersh was dragged off into Hamas captivity, Chicago-born Jon and Rachel Goldberg-Polin became the global face of a campaign to keep the hostages’ cause alive. As they strive to present their son’s case to a hostile world, Hersh’s parents are trapped in a reality that few can understand

Pesach came, and with it the first sign of life from Hersh Goldberg-Polin in six long months of captivity. Hamas’s psychological warfare department released a short video of the 23-year-old Israeli-American hostage who was snatched from the Nova festival on Simchas Torah morning. The Arabic and English-subtitled clip showed that the once-smiling, happy-go-lucky young man who never raised his voice to anyone was now a gaunt, pale hostage with a Muslim-style haircut and deadened eyes.

Reading from a script prepared by his Hamas captors, edited to emphasize his agitation, he raged. “Binyamin Netanyahu and government — you should be ashamed of yourselves for torpedoing every hostage deal. While you sit having lunch with your families, we sit here without water, food, or sun and the treatment that I so badly need,” said Hersh gesturing with his half-healed stump of an arm.

That was what viewers worldwide saw. But in their home just a few dozen miles from the Gaza tunnel hiding their son, Hersh’s mother Rachel Goldberg-Polin detected something else. “I still felt whispers of Hersh, in the way that he turned to us and said the names of his sisters and said, ‘I love you — stay strong.’ ”

Call that intuitive reading what you will — desperate hope, a mother’s love — but if you meet Jon and Rachel Goldberg-Polin, you’ll see that it’s 100 percent authentic. There’s a certainty born of some sense of spiritual connection flowing between Jerusalem and that dreadful bunker in Gaza that tells them that Hersh will come home. Rachel in particular talks about his well-being with a startling confidence: “I imagine that he’s bored because he always needs to be reading, and wonder whether he’s learned Arabic from his captors — he has a photographic memory.”

That certainty has transformed Rachel into the global face of an effort to keep the hostage story alive. Along with the now-famous white masking tape with the number of days that Hersh has been held captive that she wears every day, her mix of drive and destiny have born Rachel into the White House, the Vatican, the United Nations, the world’s front page, and countless news shows and rallies.

In a previous life Jon was a serial tech entrepreneur and Rachel worked in mental health. That’s all gone. Now, they work together for 20 hours a day. Along with a small team, they relentlessly strategize, work for media exposure, and lobby leaders all over the world.

Their message is simple, scrupulously avoiding politics, emphasizing universal themes: “Just imagine that this was your son and daughter,” they tell the interviewer, politician, or potential influencer. It’s a highly-strategic formula that has gained them entrée to a media that has largely shut the door to Israel’s narrative.

Like long-distance runners who’ve discovered unimagined reserves of endurance, there’s a tightly-strung energy to both of Hersh’s parents. But there’s something volcanic about Rachel’s calm — a pain that occasionally breaks through the deceptive serenity with which she goes about the fight for her son’s life.

Essence of Honor

The current iteration of Rachel Goldberg-Polin has no time for circling, or beating about the bush; there’s an elephant in the room and so she gets to it straight away. “If we’re a shomer Shabbos family,” she asks rhetorically, “why was Hersh at a music festival on Simchas Torah?”

I hadn’t planned to start with what felt both obvious and insensitive. But Hersh’s name — far too Yiddishy for a young Israeli — indicated that there was a religious story that had been missed in the countless media appearances that the couple has made.

“Jon was lucky to be born frum from birth, into a nice Orthodox family in Chicago, where I also come from,” confirms Rachel, “but mine was totally unaffiliated. I wasn’t raised religious, but always had a very Yiddishe neshamah. I felt drawn to Yiddishkeit. So I always thought that Hershel was a beautiful name.”

“My grandmother — who called me ‘zeeskeit’ — was raised nonreligious but she bought her meat at a kosher butcher because her mother had done so. It was only through a weird twist that my mother started to keep a kosher kitchen when I was in seventh grade.”

That twist was when Rachel’s mother invited a family to dinner, and they declined, explaining that they would only eat in a kosher home. She didn’t know what that was, so she enrolled in a Chabad class to find out. She then decided that she wanted every Jew to feel comfortable eating in her home, so she began keeping kosher.

Thus began a journey that took Rachel to an Orthodox day school for the last year of studies before entering the local Orthodox high school. That first day at Hillel Torah in Skokie changed her life.

“I proudly turned up wearing purple corduroy pants only to discover that none of the other girls wore pants — but all day, not one person said anything to me. That changed my life. I was thirteen years old and I went home and said to my mother, ‘No one was mean to me — that’s the world that I want to live in.’ ”

Jon was a year behind Rachel at high school, but it was only years later when both were in Israel that they reconnected, and eventually married. Before making aliyah, the couple spent some time living in Berkeley, California, and Hersh was born there — a fact that they jokingly use to explain their son’s hippie, granola-crunching vegetarian ways.

All of that is prologue to the story of Hersh’s own evolution. As a religious family, the Polins sent their son — who has two younger sisters, Libby and Orly — to religious elementary and high schools in Jerusalem. He used his excellent memory to win a prize for memorizing Mishnayos. A school photo shows him and his friend Aner Shapira — who was famously killed after throwing grenades out of the bomb shelter the pair were hiding in on October 7 — wearing tefillin. But all that changed two years ago.

“Hersh came to us and said, ‘I’m not keeping Shabbat the way that you keep Shabbat, but I will never disrespect you,’ ” recalls Rachel. “I thought to myself, “How is that going to work? But what we saw the last two years is that we never saw him without a kippah, in our house. ‘This is your home, and I’m always going to respect you,’ he told us.”

Hersh took that self-imposed commitment seriously. He would wash before bread, leave soccer games early on Friday to join his family for Kiddush, and sit in the succah even when his parents weren’t in the house.

“The day before Simchas Torah, we came home to discover him sitting in the succah despite the fact that it was a heatwave, and there were plumes of dust from the construction happening next door. I said to him, ‘Why are you sitting outside?’ He said, ‘Mama, it’s Chol Hamoed Succos — you think I‘m not going to sit in the succah?’ ”

That sense of respect for his parents was Hersh’s essence, says his mother. It meant that he continued to go to shul, even though davening wasn’t part of his world anymore. “If you’re not keeping Shabbos, then spending the morning in shul is annoying. I asked him why he continued to come to shul with us, and he said, ‘I don’t want Dada to sit alone.’ ”

And that respect for his parents is why the Polins are utterly convinced that their son — despite being a high-value male hostage in the hands of a murderous terror group — is coming back.

“It’s in the Aseres Hadibros, that the reward for Kabeid Es Avicha is a long life,” says Rachel. “He has a long life to live, because he showed respect for us even when he wasn’t living the life that we live.”

Millions of viewers watched as Hersh – in a first sign of life and identifiable by his injured arm — read off the Hamas script

Facing the Music

That same pattern played out on the fateful Simchas Torah. The night before — Friday night — Hersh had accompanied his parents to shul for hakafos as in previous years. He accompanied them to the Shabbos dinner that they ate with family friends a few minutes away, holding his backpack because he intended to go camping afterward. On the walk from shul, Hersh recounted different things that had happened on a recent trip to Europe.

“At about 11 p.m.,” says Rachel, “he kissed me, kissed Jon, thanked the hostess, and as he walked through the door said casually, ‘Love you, see you tomorrow.’ And that was 235 days ago.”

The next morning, Jon left for shul at 7:30, with his wife and daughters slated to follow. By 8:00 a.m., they were rushing to their air raid shelters with Israel under massive rocket bombardment. With no communication, they had no idea what was happening, but Rachel knew that there was something out of the ordinary.

“I knew that Hersh was somewhere out in the open, and that bombs were falling. So I decided that although I would never normally do so, I would turn on the phone.”

It was 8:20 a.m., and there were two messages from her son from 8:11, just a few minutes earlier. One read, “I love you.” The second said simply, “I’m sorry.”

By that stage, Jon explains, there was already carnage all around the Nova festival.

“He was in the migunit — the bomb shelter near the Re’im music festival where Hamas killed many people. People had died there. Hersh thought that he was going to die, and felt bad that we were going to lose our only son.”

Rachel desperately tried calling him, and wrote three texts: “I’m leaving my phone on.” “Are you OK?” “Please let me know,” they read. But there were no more blue ticks on the WhatsApp group. The last cell phone signal was at 10:25 a.m., traced to Gaza. By that time, Hersh may not have had the phone himself anyway, but afterward all contact was lost.

Before the Pesach video clip, the last sighting of Hersh was when Hamas terrorists entered the shelter and he was caught on film with the lower half of his left arm severed, the bone exposed by a wound from the carnage inside the enclosed space. Trained in first aid, he appeared to have fashioned a makeshift tourniquet to stem the bleeding by the time he was loaded into the back of a truck and driven away.

Whereas Jon has visited the scene of their son’s kidnapping, Rachel has refused to do so. “I couldn’t — I just couldn’t,” she says.

Since then, the Polins have joined hundreds of other Israelis whose loved ones were dragged into Gaza, in a nightmarish limbo.

“We all live on a different planet than the rest of humanity, with a slow-motion trauma. It’s not the same dimension of experience as normal people. It’s like Yaakov Avinu who couldn’t find comfort because Yosef was in fact alive. We’re suspended,” Rachel says.

That religious dimension has found expression through a heightened sense of the power of prayer. Behind the door in their home, the Polins have a large picture of their son hanging that they used to take to rallies. Now it joins Rachel’s daily tefillah. During Baruch She’amar, she finds herself repeating “Podeh u’matzil,” multiple times. When she says “Somech noflim” in Shemoneh Esreh she looks at Hersh’s poster, and when she gets to “V’rofei cholim,” she looks at her own left arm where Hersh’s arm was amputated, and continues, “U’matir asurim, u’matir asurim, u’matir asurim.”

Each paragraph has something connected in the most visceral way to Hersh, until she gets to Modim where she thinks of her thankfulness for her husband, two daughters — and her hostage son.

“I’m grateful that I can still be grateful,” she says.

That extraordinary capacity to find the positive in their living nightmare is what drives the couple forward. But sometimes it all boils over.

“That’s my davening room,” Rachel gestures to the back of the Jerusalem coworking space that is their base. “Everyone here knows that when it gets too much, I head there to scream out a few Tehillim or just talk to Hashem.”

While Jon doesn’t want to take political sides, one thing is clear: “As a human being, you can never call for a cease-fire without it being explicitly clear that the hostages need to be released unconditionally”

Universal Value

Within days of their son’s capture, the Goldberg-Polins had developed a strategy: Don’t wait for the government to act; go solo and talk to any leader or influencer that they could reach to keep Hersh’s case from fading. “We don’t know who’s going to be the shaliach; who will be Hashem’s vehicle to unlock this quagmire,” says Jon, “so we have to talk to lots of powerful and influential people.”

That effort — unfolding separately from the government’s contacts and the far larger Hostage Family Forum in Tel Aviv — is a small, yet intense operation. Besides Hersh’s parents, there are three full-time staff working on PR, social media, and operations. Crowdfunding, generous grants from Jewish foundations, and the hospitality of the owners of the coworking hub have enabled the whole operation to roll forward.

That’s because the Polins’ campaign is not just about one person, or about the “American Eight” — the group of dual Israeli-American citizens held hostage in Gaza: They raise awareness for all the hostages, in a particularly effective way. Type in Hersh Goldberg-Polin, and an alphabet soup of media outlets pops up. NBC, CBN, New York Post, London’s Telegraph, Dr. Phil — interviews in these outlets are quoted and republished in many others across the world. That’s a tribute to the effectiveness of the “Bring Hersh Home” campaign’s media savvy, but also to the organic traction of the effort itself.

It’s not just their native English and understanding of the American media landscape that has made the Polins such effective faces of the hostage struggle. It’s the human, universal message that they relentlessly convey.

“If someone’s a parent they can picture what it would be like, or if not, they can picture what their own parent might be feeling if their child was captured,” Rachel said in a recent interview to a big news channel. There was no raging against the terrorist evil, or blaming one party or another — just basic humanity that is very hard to disagree with.

And then there’s the fact that the hostages come from so many countries and religions — not just Israeli or Jewish. “I’m desperately telling the world because I happen to speak English, that I haven’t heard advocacy for the Thai, Buddhist, black Christians, and others,” she says.

In an interview with Time magazine, she referenced the most visible external sign of her campaign — the white masking tape she wears with the number of days since her son disappeared.

“You know, when you wear the same thing, people can get comfortable with it,” she said. “This tape makes people very uncomfortable. It’s in your face saying for 193 days you’ve allowed 133 human beings from 25 different countries; who are Muslim, Jewish, Christian, Buddhist, and Hindu; who range in age 86 years — you’ve allowed them to stay underground suffering.”

That strategy – highlighting the many non-Jewish and non-Israeli hostages as a way of universalizing the cause – works in the Polins’ appeals. Could Israeli government messaging have benefitted from this approach, especially in the early weeks of the war? Given the tidal wave of anti-Israel hate that quickly painted a just war as murderous, it’s hard to think that a different strategy would have had a different outcome.

Two Truths

The other element in the Polins’ approach is their empathy for the other side — seemingly both a smart strategic move, and a genuine sentiment.

“People don’t seem to be able to hold two truths, but we’re a very advanced species and we can hold two truths,” she tells interviewers. “People feel that you either can be worried about the innocent civilians in Gaza, or you can be worried about the hostages. The truth is the hostages are also some of the civilians who are innocent in Gaza. Of the thousands and thousands and thousands of innocent civilians in Gaza, I know one of them. Really well.”

Whatever their success in getting a hearing, optimism can be hard to maintain when meeting leaders who greet them with sympathy but little else of practical value.

“Everyone feels for a mother in pain,” Rachel says. “But wanting to help and doing something about it are very different things.”

Gaining international traction in a world where Israel has lost the narrative battle and faces immense pressure over allegations of genocide is also a growing challenge. Despite their success in getting through to a slate of world leaders — some of whom can’t be named because of the sensitivity of the contacts — Israel’s deteriorating environment has affected the struggle to tell the hostages’ story.

“On our trips to the US, we’re now seeing elected officials sometimes say, “Well, if you want to bring the hostages home, you need to tell your country to dial back the war,” says Jon Polin. “Our response is, ‘You can worry about Gazan civilians, but as a human being you can never call for a ceasefire without it being explicitly clear that the hostages need to be released unconditionally.’ ”

While a hostage release likely means the disastrous scenario of leaving Hamas in power, it doesn’t deflect the intensity of a mother’s cry whose child has been left behind in a Gazan dungeon

Above the Fray

That refusal to get swept up in any of the narratives abroad becomes much more fraught when applied to Israel. Over in Tel Aviv, regular demonstrations from left-leaning groups are attempting to pressure the government into agreeing to almost any terms to win the remaining hostages freedom. With many of the same actors and funding as last year’s anti-justice reform campaign, it isn’t hard to see some of the ‘Bring Them Home Now” campaign as just the latest iteration of the old anti-Bibi campaign.

A few miles away from the Polins’s base, outside the Knesset is a counter-movement: the so-called “Gevurah Forum” tent, a group of parents of soldiers who’ve lost their lives in Gaza, who say that any weakness when it comes to prosecuting the war effort is an insult to their children’s memory. This group — mostly right-leaning politically — contend that hostage release will only come about through unrelenting military pressure on Hamas, and treat the ongoing negotiation efforts suspiciously.

Both Jon and Rachel refuse to be drawn into the poisonous politics — in fact, you’d be hard-pressed to hear a word of criticism about the conduct of governments in Israel and America.

“We have a mission to save as many hostages as possible, including our son,” they say. “We have no judgment for the way other families are choosing to deal with the excruciating pain, but our hashkafah is not to do the politics.”

But inevitably, in the binary world of stark choices that the war and hostage negotiations have thrust on the country, the Polins’ advocacy for their son comes down on one side of a furious debate. Despite their determination not to get involved in the political aspect of the battle around the hostage issue, the Polins are very clear where they stand on the practical side of the question.

When I put to her that there are two legitimate sides to the anguished debate inside Israel about the latest hostage deal, which would likely leave Hamas undefeated if it went ahead, Rachel loses her equanimity — the only time that she does so in the interview. It’s as if the volcanic pressure has become too much and it must vent.

“Forget Hamas or whether there will be future wars! GET THEM OUT! GET THEM OUT!” she says of the recently released video of the five female soldiers captured by Hamas. “That’s the most Jewish thing that we can do,” she says with unnerving intensity. “We have to bring these poor hostages home NOW!”

In the world of decisions in which a hostage release likely means leaving Hamas in power, that could be a disastrous path for Israel to take, leading to more bloodshed down the road. But Rachel’s cry is the voice of so many mothers whose children have been left behind in Gaza.

Long Road Home

This life of nerve-racking advocacy, painfully personal diplomacy has been thrust on them, but the Polins are determined to continue until every one of the hostages has returned. They don’t know if they’re getting anywhere in their Sisyphean struggle, but at least they can look themselves in the mirror as parents and know that they’re doing their best — the rest, they know, is out of their hands.

As they do constantly, Rachel’s thoughts come back to Hersh. “Since seeing the video of him, I’ve had to change how I think of him. I put my hands up to bless him and picture him as he appeared in that video.

“Is he teaching his captors English?’ she asks, with that outer conviction and connection to her son who’s a world away. “Is he using his photographic memory to remember all the American presidents, or the Mishnayos that he learned?”

And so it’s been seven unreal months, when the passage of time has been marked by masking tape on shirts, and their son lies shackled by Hamas in an underground dungeon. It’s been seven months since normal life stopped, and people started reacting to them viscerally, as if they were burn victims with horrible wounds.

“People are very uncomfortable to meet us, including politicians from all parties,” says Rachel resorting to the metaphors that she’s become adept at inventing. “It’s as if we have tzaraas; we’re people’s worst nightmares — they don’t want to catch what we have.”

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 1014)

Oops! We could not locate your form.