New Day, New Page

Zvhil rosh yeshivah and veteran maggid shiur Rav Michel Zilber shares the secret fueling a century of Daf Yomi

Photos: Elchanan Kotler, Mattisyahu Goldberg, Mishpacha, and Family archives

When Zvhil rosh yeshivah and world-renowned Shas baki Rav Michel (Yechiel Michel) Zilber started recording his iconic Daf Yomi shiurim for Kol HaDaf in the 1980s, the “studio” was right here where we’re sitting, in his dining room. There were no fancy microphones or special sound equipment — just a large tape recorder that Rav Zilber had borrowed from his father, a large “Peninim” edition Gemara, and the baal habayis himself — a gaon with an exceptional gift for explaining. Each day, after shushing his children, he would press the record button and begin to speak about the daf. Even if Schottenstein existed then, he would never have used it — who needs it, if the entire Shas is at your fingertips?

Tens of thousands of people the world over consider themselves Rav Zilber’s talmidim: rebbes, roshei yeshivah, avreichim, and laymen — all of his regular listeners. Toward the end of his life, when he’d lost his vision, the Vizhnitz-Monsey Rebbe ztz”l would spend hours every day listening to Rav Michel Zilber’s tapes in Yiddish.

The presentation was always clear and concise: Every daf took exactly sixty minutes, the length of an average tape. Thousands of people connected daily, either with the Kol HaDaf tape gemach or the few shiur phone hotlines.

Reb Michel might be the rebbi of so many Yidden, but in essence, he’s also their chavrusa, having not only learned from him, but with him as well.

Sixty years after Rav Meir Shapiro’s Daf Yomi revolution in Poland, beginning on Rosh Hashanah of 1923, the next stage began in Jerusalem with Rav Zilber. Now, a hundred years later, it’s hard to imagine how Daf Yomi could reach every corner of the world without these shiurim.

Over the years, many new shiurim for Daf Yomi — all types for all types — have opened. But Rav Yechiel Michel Zilber was the Nachshon, the pioneer — one of the first marbitzei Torah to harness the evolving technology for the benefit of disseminating Torah.

But Rav Michel’s mission didn’t end after the recording. His daily quota of learning is still mind-boggling, matched only by that of Rav Chaim Kanievsky ztz”l. Rav Michel makes a siyum on Talmud Bavli and Talmud Yerushalmi each year on Succos. For that, he studies seven blatt of Bavli and four blatt of Yerushalmi each day. In addition, he makes a siyum on Shishah Sidrei Mishnah each month. Toward that end, he learns 18 chapters of Mishnayos a day. So in effect, each year he makes a siyum on the entirety of Torah.

On Rosh Hashanah night, in 1923, three weeks after the famous declaration of Rav Meir Shapiro in the Viennese auditorium at the first Knessiah Hagedolah that August, the Imrei Emes of Gur asked for a Maseches Berachos and he sat down to learn the first daf.

Yidden did the same thing around the world, and are doing it to this day, assisted in no small measure by Rav Michel Zilber. The cassettes were replaced by compact discs, and then upgraded to digitization, and today, there isn’t a single digital platform for the dissemination of Daf Yomi that doesn’t have Rav Zilber’s shiurim at the top of the roster.

The Rav is an ish Teveria in his soul. He was born in that Galilean town to a family of Slonimer chassidim who had resided there since the aliyah of Rav Menachem Mendel of Vitebsk and his disciples in the 1700s. His paternal grandfather, Reb Ezriel Chaim Zilber, was a Gerrer chassid who came to Eretz Yisrael during World War I. In his youth, young Michel became a talmid of the Nesivos Shalom of Slonim, and later, earned a reputation as one of the lions in the Slabodka yeshivah. After his marriage, he moved to Jerusalem, where he continued to learn and learn.

“One summer,” he says, “I wanted to show my children what real learning meant, Now, the previous Klausenburger Rebbe lived in Netanya, but he came to Teveria frequently to visit Rav Meir Halberstam of Tchakava. It was the middle of the summer and were staying in Teveria then, and I took my two older daughters, one was fourteen and the second was twelve, so they should see what it means to learn Torah with mesirus nefesh. I told them, come, you won’t regret it.

“It was two o’clock in the afternoon. Sweltering. The Klausenburger Rebbe sat under a canopy, but the heat was oppressive. He sipped a little juice, but learned the whole time, with deep concentration and oblivious to everything around him. It was boiling outside and inside, he was burning like fire.

“Here was a person who lost his wife and 11 children in the Holocaust, who every Shalosh Seudos would say Torah from his bunk. Did he think maybe he should give up? Not at all! The first thing after the war, he built a mikveh. There were lots of Jewish families in the DP camp, and they needed a mikveh — that his only consideration. And they needed a yeshivah, they needed to learn. So he found a Slonimer chassid, a Russian, named Yaakov Lechovitzky, and they created a yeshivah. They didn’t ask who was coming to learn in the yeshivah. Everyone was invited.

“People like the Klausenburger Rebbe zy”a — they have internal vision. They see the problems from the start, and resolve them right away. The Rebbe got remarried, but he didn’t want to go to the chuppah. ‘She believes I’m a tzaddik,’ he said, ‘and I don’t want there to be a mekach ta’us, a mistaken acquisition…’ In the end, he told her so she would know the truth. ‘I’m a very simple person,’ he said, ‘but I have one virtue, that I am ready to be moser nefesh for kiddush Hashem.’

“I’d been learning with Rav Mordechai Elefant of Itri,” continues Rav Zilber, ever the raconteur (but where does he find the time?). “I was his chavrusa, and also his confidant. And one day, he confided to me that he was thinking of closing down the yeshivah — it was getting too difficult to bear. And so, he decided to talk it out with the Klausenburger Rebbe.”

The Rebbe had told him, “Mordche’le, it’s all narishkeit (nonsense). Laniado, Baniado, there is nothing that compares to a daf Gemara with Tosafos.’

“When I related this, a lot of people didn’t understand. How could the Rebbe call such important things as establishing Laniado Hospital ‘narishkeit’? In Likutei Halachos, the same question comes up. The Gemara in Yevamos says that Rava engaged only in learning — and he lived just 40 years. Abaye, who was also busy with chesed, lived 60 years. The Chofetz Chaim asks a simple question: If a person is learning Torah, and a mitzvah arises that others can do in his stead —he has to continue learning. You are now learning, and you have to go to the grocery. If there is no one else, you will go. If there is someone else who can and wants to go, keep learning. So why didn’t Rava live longer?

“The Chofetz Chaim says: There are things that only the gadol hador can do. Gemilus chesed is only the gadol hador. Abaye was mechadesh that what the gadol hador is permitted to do is actually an obligation. There is a dispute about what is called ‘can be done in the hands of others.’ Establishing Laniado Medical Center — that’s something only the Klausenburger Rebbe could have done. Other hospitals were built, Beilinson, Ichilov. But a frum hospital where the staff is religious and tradition embraced, that’s something only the Klausenburger Rebbe could do. Yet after he finished establishing Laniado, he went back to the Gemara and Tosafos, and those were his real partners.”

When does he have the time? Rav Michel Zilber is not only the world’s biggest seven-year-cycle Daf Yomi rebbi, he makes his own siyum on Bavli and Yerushalmi every single Succos

IT

all began in a little house in Teveria before the establishment of the state. Reb Leibel (Meir Aryeh Yehuda) Zilber, a Slonimer chassid who was in charge of the health bureau in Teveria, was sitting at a Daf Yomi shiur delivered by his rebbe, the Birchas Avraham of Slonim. He heard from his Rebbe that “someone who doesn’t speak against gedolei Yisrael of any community will merit children who are yerei Shamayim.”

Reb Leibel took this seriously, and from that point on, there was not a word uttered in his home against gedolei Yisrael. On Erev Yom Kippur 5703/1942, Rav Asher Werner, the legendary rav of Teveria, saw Reb Leibel and his wife preparing for Yom Kippur with such purity and exceptional yiras Shamayim. He was very moved by the scene and promised Mrs. Zilber, “You will have a son that will illuminate the generation with his Torah.”

A year later, on Erev Yom Kippur 5704/1943, Yechiel Michel was born. To this day, Reb Michel attributes his Torah to the strict rule in the home in which he grew up — not to speak against a single gadol b’Yisrael.

Rav Zilber’s bar mitzvah took place on Erev Yom Kippur. Rav Asher Werner, the rav of Teveria, had already had an eye on the up and coming illui. “Ehr vet noch zein a gadol b’Yisrael, he will yet be a gadol b’Yisrael,” he would say of him.

Rav Zilber saw many gedolei Yisrael and had a special kesher with the Beis Yisrael of Gur, “this giant of a Yid to which there wasn’t a corner in chareidi Jewry that he didn’t pay attention to, to see if something had to be taken care of.” Rav Zilber says.

“I’ll tell you an interesting story. My shver was Rav Velvel Fishman, a prominent Boyaner chassid and a baal tefillah in Boyan. He lived in Batei Varsha, near Meah Shearim, and next door to him lived a Gerrer chassid named Reb Mordechai Yidel Leifland. One year on Succos, Reb Mordechai Yidel built a new succah. At the time, this was a rare and exciting occasion. Not everyone in Jerusalem of those days could allow himself the luxury of building a new succah.

“He went to the Beis Yisrael and asked: ‘Can the Rebbe come and see my new succah?’ The Beis Yisrael didn’t respond.

“I was a young avreich then and didn’t yet have a succah of my own, so I slept in my shver’s succah. One night, on Chol Hamoed, at two in the morning, I heard a stick knocking on the wall of the neighboring succah: “Peiger [lit. peger, an animal carcass] why are you sleeping?’ It was a very familiar voice — the voice of the Gerrer Rebbe. Reb Mordechai Yidel was hoping the Rebbe come visit him in the succah, but he assumed the Rebbe would come during the day. The Rebbe, though had his own calculations, and showed up at 2 a.m.

At the age of 13, Reb Yechiel Michel began to learn in the Slonimer yeshivah and became a close talmid of the Nesivos Shalom of Slonim. Later in the summer of 1962, he switched to the Slabodka yeshivah in Bnei Brak. In those years, one couldn’t learn b’chavrusa with the roshei yeshivah unless he’d already been in the yeshivah for two years, but the policy was changed for the young talmid from Teveria.

In Slabodka, Rav Yechiel Michel became a talmid of roshei yeshivah Rav Mordechai Shulman and Rav Baruch Rosenberg ztz”l, as well as best friends with fellow talmid Rav Dov Landau. He also became close with Rav Yechezkel Abramsky, whom he still considers his rebbi muvhak.

In 1968, Rav Mordecahi Elefant established Yeshivas Itri. He asked the young talmid chacham who had come from Teveria to Jerusalem to teach in his yeshivah. And so, at the young age of 26, he became one of the roshei yeshivah in Itri, where he taught for decades. In 1991, the Zvhiler Rebbe asked him to serve as rosh yeshivah of the chassidus, although the yeshivah had, and continues to have, bochurim from all chassidic communities. Rav Zilber still delivers shiurim in the yeshivah every day.

Standing behind Rav Avraham David Rosenthal, the rav of Shaarei Chesed, and the Nesivos Shalom of Slonim — the rebbe of his youth and on

A

nd then, toward the end of the 1980s, the moment arrived that would have a lasting effect on the manner of Torah learning for masses of Yidden around the globe. Rabbi Eli Teitelbaum a”h, who managed an initiative in America called the Dial-a-Daf, which recorded shiurim on Daf Yomi in English, wanted to expand it to Hebrew and Yiddish. He turned to his friend Reb Elchanan Zilber, owner of Khal Chassidim hall in Boro Park and a brother of Rav Michel Zilber from Jerusalem. Reb Michel sent a sample shiur, and the fluency and clarity left no room for doubt: The generation needed Rav Zilber’s shiurim. There was one condition: Every daf had to be 60 minutes, not more in the event of longer dapim and not less when the daf was shorter.

“I made two tapes and sent them with someone traveling to New York,” the Rav recalls. “Rabbi Teitelbaum got them and took them to the Novominsker Rebbe ztz”l. A few days later I received a message that the Rebbe was impressed, and that’s how we continued.

Those tapes were made here, in this dining room, as his children “suffered” through their childhood having to be quiet so many times during the day.

“There’s an ironclad rule,” the Rav says. “There’s an inverse relationship between the beauty and size of a dining room, and the intensity of Torah that it contains.”

When the Rav began the revolution of recorded shiurim, of course there were the naysayers who were concerned that people would no longer sweat it out with their learning.

“Well, even if there was such a concern, over the years, it turned out to be for naught. One must spread Torah as much as is possible, and not be lazy about it,” he says. “I remember once that longtime Agudah MK Reb Menachem Porush asked me, ‘You speak for an hour, and never once do you stammer. How is that possible?’ I’ll tell you. It’s all from Shamayim. A Yid is given a zechus. It’s not simple.

“And it took some getting used to. I would come to events, to tishen and big simchahs, and suddenly famous rebbes were standing up for me and whispering, ‘We are talmidim — through the tapes.’ Only then did I realize how far it went.”

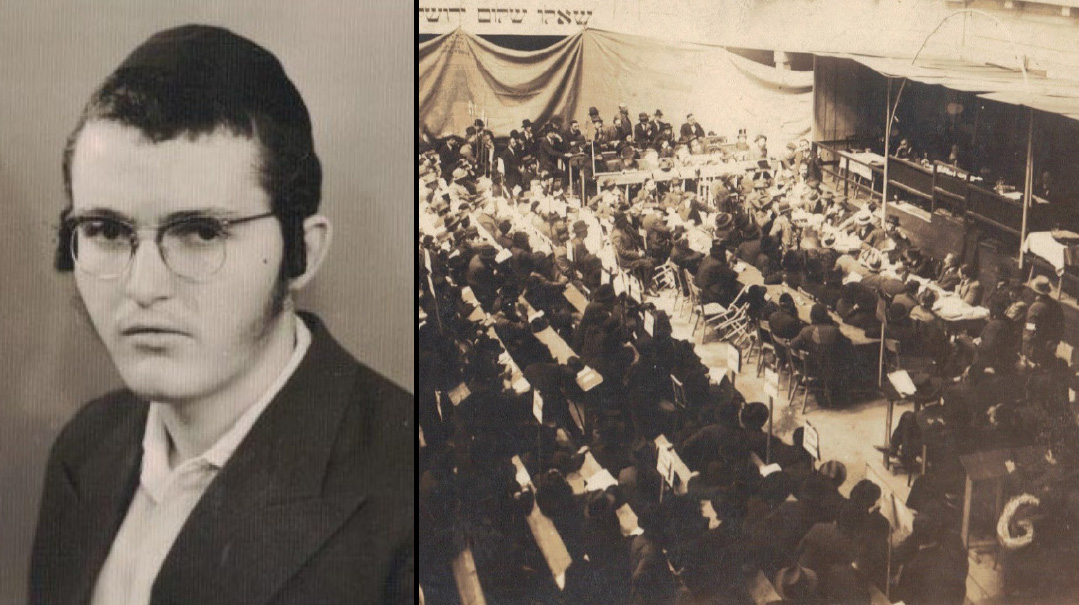

(From right to left) Rav Zilber as a young rav; the first Knessiah Hagedolah a hundred years ago, where Rav Meir Shapiro changed the world of Torah learning

IT’S

safe to say that all of us want a bit more Torah in our lives, but how do we, the “simple folk,” attain yedias haTorah?

“Let me ask you a question,” the Rav says. “Does a person ever forget the name of his child, or his address and phone number? Basically, what’s important to a person, he remembers. So we need to add Torah to the list of important things — and suddenly, you’ll see that you remember. But it doesn’t happen in a day. You need to start and then practice. It takes time, but at the end it happens.”

That, says Rav Zilber, is the key. Just start. “It doesn’t happen in a day, but that doesn’t mean you don’t start. I recently heard a vort: A person comes to Beis Din shel Maalah after 120 years. He is asked, why did you sin so much? And he says to HaKadosh Baruch Hu: ‘You sent me a yetzer hara, he didn’t let me live.’ And he is answered: ‘There is no shaliach lidvar aveirah.’ That is the answer to everything. You need to decide what is a mitzvah and what is an aveirah, and then to do just the mitzvos and refrain from aveiros.

“Someone once said to me, ‘It’s hard for me to go to shul.’ I told him, ‘I see you manage to get to the grocery just fine. Only to shul it’s hard for you to go? For me it’s the other way around…’

“I believe it’s a mitzvah to publicize what it says in Chofetz Chaim, Hilchos Talmud Torah: that a person who toils for a living all day, but he has a set time to learn Torah, that is what’s called Toraso umenaso — that Torah is his true craft.”

“I actually once said this in a shiur. There is a piece in Talmud Yerushalmi as follows: There was a big merchant, and he had a set time when he learned Torah. Other dealers came to do business with him and his brother said to him, ‘So and so has arrived.’ But he refused to stop learning and said, ‘If Hashem wants me to do business with them, they will come at a time when I am not learning.’ The merchants heard this and said, ‘Such a faithful person, we want to do business specifically with him, even if it’s double the price.’ And the Yerushalmi describes this person as one for whom ‘Toraso umenaso,’ Torah is his craft.

“It’s not the definition of someone who sits all day and learns in kollel! It is someone who really sees Torah as a craft, a profession. And this profession is something that every Jew can acquire.”

With Rav Yaakov Hillel, head of the Ahavat Shalom yeshivah for the study of Kabbalah. On Rosh Hashanah, unbeknownst to most, Rav Zilber would sometimes head over to the yeshivah for the special mystical kavanos in tekiyas shofar

W

hat is less known is that Rav Zilber’s dining room not only absorbs Torah, it is also a source of tremendous chesed and assistance to others. One cause that is very close to Rav Zilber’s heart is Seeach Sod, an institution for special children and their families. Rav Zilber is one of the pioneers who changed the perception in the chareidi community toward these children, and what many don’t know is that indeed, although the founder of Israel’s flagship frum institution for the special-needs community was a Gerrer chasid named Rabbi Dov Levy a”h, whose son was diagnosed with Down syndrome in 1971, Rav Zilber was the force behind him. He too has a special child, a 52-year-old son whom he and his wife raised at home at a time most of these children were put into secular institutions.

In those early days, when there wasn’t a single religious institution in Israel that catered to special children (many parents resorted to placing their children in Christian centers such as St. Vincent de Paul), Rav Zilber decided to take action. He closed his beloved Gemara and began to travel around the world, connected with a wide network of gvirim and gedolei Yisrael, including the Lubavitcher Rebbe and Rav Moshe Feinstein. The school (which has since closed) was called Limudei Hashem.

From then until today, there has been a complete transformation in the chareidi world — and in society at large — in the treatment and care of special children and support for their families. Rav Zilber and his colleagues helped create a national awareness and facilitated proper frameworks for these neshamos, and most of all, put a stop to the shame about their existence.”

Rav Zilber was a trailblazer — one of the first people of his stature to bring such a child out to the public. “When he was growing up, I declared, ‘When I come to Olam Haba, they will want to give me a reward for saying shiurim on Kol HaDaf. But there is one thing that I will demand — that I was a father to special children, that my wife and I counted out each bill we raised to establish a home for them.

“My rebbe, the Nesivos Shalom, once said to me, “For saying shiurim you don’t deserve anything. You enjoy the learning. But saying one good word to a struggling child or to his suffering father — for that you will be rewarded in Shamayim.

“Because each of us has an obligation to those around us, to open our eyes and feel for the other person’s discomfort and pain,” the Rav says. “And when you start looking, Hashem gives siyata d’Shmaya and puts the right words into your mouth.”

Mishpacha’s Yisrael Groweiss and Aryeh Ehrlich together with Rav Zilber in the hallowed dining room where siyumim are made, and that once served as a recording studio with a tape recorder

IT’S

not only special children and their parents. Somehow, Rav Zilber’s dining room had become an address for so many people and institutions in need. The Gemara is always open, but the huge heart is open even more. Sometimes the Gemara is closed, and the tears of a widow or a suffering parent flow freely.

Rav Zilber sees it as his shlichus: “People need to take responsibility for the others in their orbit,” he says. “Anyone could occasionally be needy. You live in a neighborhood, you have an elderly neighbor, take an interest. Sometimes with one good morning you can save another Jew.

“Here is something that happened during Covid: I live in a building with 24 families. There were minyanim here three times a day, and we were pretty well taken care of, between our children. Nine steps down from us lives a woman. One day, she knocked on the door and said to me, ‘Rav Zilber, if you need anything at all, I’ll bring it.’ Baruch Hashem we didn’t need anything, and the children helped with whatever we needed, but this gesture — that is a zechus to come to Yom Hadin with.

“You’re in shul and you see a Yid come in? If you are not up to a place where you can’t talk, say ‘Reb Moishe, gut morgen.’ You have no idea what a good feeling you’ll give the other person. Wow! Someone is thinking about me! A minute ago, he was a bit down, and suddenly, everything turns around for the good.”

To sharpen the point, the Rav tells of a Yid he knows who had a daughter, and it was going very hard in shidduchim. The whole household was depressed from it. “This Yid came here, and I gave him just one piece of advice: ‘When you come into your house, don’t talk to anyone until you’re calm enough to say a good word.’ Almost instantly, the bad vibes and contentiousness stopped.

“Let me share another story: For years, we’ve had a custom that the Shabbos after Pesach, we go to Tzfas. The deputy mayor of the city gives me his apartment for Shabbos, I come already on Thursday, then we go to Meron for Minchah and Maariv, then daven haneitz in Meron, stick around for Minchah on Erev Shabbos, and come back on Sunday morning,

“This year when I came, it was very crowded. I went in to daven in the cave of Rabi Elazar and a Yid, a Sephardic Jew, said to me, ‘Here, there is room for you.’ I sat down and got myself together, my grandson right next to me. Then a young man came over and told me that he has a brother who has been married for 14 years and doesn’t yet have child, lo aleinu. Someone told him, ‘Stick around Meron and when Rav Zilber comes, get a brachah.’ I said to him, ‘You believe in all this nonsense that Rav Zilber can give you a brachah?’ And he said to me, ‘I have to do something.’

“I told him: There’s a grocery store in your neighborhood. Today, in every neighborhood grocery, you can find a mother with lots of children who comes to the register and can’t pay. Go to the cashier and say, ‘I’m paying for this woman’s purchase.’ On the spot, this man called his wife and said, ‘Rav Zilber said to go down to the grocery and see if there’s someone whose order needs to be paid for.’ She went down, and there was a woman there who struggled to pay and started putting things back on the shelf. This man’s wife went over and said to her, ‘Take it all, I’ll pay.’ That’s called siyata d’Shmaya. When a Jew wants to do a good deed, he gets assistance from Above.

“In these kinds of things, one is not allowed to be a ‘chassid shoteh,’ as the Gemara calls it in Maseches Sotah (21a). It’s very interesting that whenever you get onto a bus and a woman needs someone to clear a seat for her, suddenly there are avreichim who are so strict about shemiras einayim, because they might notice her and will have to stand up… Of course, one needs to conduct himself with kedushah and chassidus — but that does not contradict the obligation to help people and not to ignore the needs of another. Chassidus is not meant to come on account of being attentive to one’s surroundings.

“I once heard that the Chasam Sofer made himself a cheshbon hanefesh on Erev Yom Kippur, and suddenly felt that he didn’t have enough zechusim to go to the Yom Hadin with — until he remembered that he’d once helped a widow make a shidduch for her daughter. But that same widow did not desist — she also demanded that he pay for the whole wedding. And the Chasam Sofer did that, lifnim mishuras hadin.

“Now, it’s clear to all of us that the Chasam Sofer had enough merits for Yom Hadin. But he felt that it was all within his obligations. In order to come to Yom Kippur, one needs to do something above and beyond, to stretch a little more. Lifnim mishuras hadin.

“As we come into the new year, each one of us can say, baruch Hashem, I was shomer Shabbos. I observed taharas hamishpachah. I recited Bircas Hamazon, I davened with kavanah and the like. But that is standard. Is there a way we can give something more? Can we find opportunities? Just look around. Do something good. Encourage, support, help… True, it’s possible that it, too, will become rote and standard, so next year, we’ll have to make an even greater effort. This is how I stretch myself to push through Daf Yomi, and this is how all of us can rise higher in our ruchniyus.”

Dream of the Century

The huge iron gates of the Renz Auditorium at Zirkusgasse 45 in Vienna opened and closed repeatedly for an entire week in August 1923, as gedolim from around the world came together for the first Knessiah Gedolah sponsored by the Agudah movement.

In a home nearby, a parade of young rabbanim came to visit the Chofetz Chaim in his accommodations. One of them, Rav Meir Shapiro, was a rising star in the rabbinic world. He was only in his thirties at the time, but was already rav in Sanok, one of the largest cities in Galicia. (He would become rav in Lublin in 1931, the year after his famed yeshivah opened there.) He was also one of a few Orthodox Jewish members of the Sejm, the Polish parliament, representing Agudas Yisrael.

He shared with the Chofetz Chaim some of the proposals he planned to make at the Knessiah, and one of them was innovative and even a bit fantastical: One unified daf of Gemara a day for all of Am Yisrael. The idea sounded rather farfetched to the others who heard it, as they smiled patronizingly to the young rav of Sanok, but the Chofetz Chaim was actually quite excited by the idea.

“If so, perhaps the Rav should suggest it when he speaks?” Rav Meir Shapiro asked.

“No, it’s your idea, and you will present it. But please, come a bit late to the session.”

Rav Shapiro thought this request a bit puzzling, but he soon understood: When he entered and tried to hurry unobtrusively to his place on the edge of the dais, the Chofetz Chiam rose in his honor, and as a result, the rest of the people in the hall did as well. The Chofetz Chaim had given Rav Shapiro the backing for his proposal.

A few days into the conference, Rav Shapiro had the floor — and presented the idea that changed the Jewish world:

“If all of Am Yisrael, wherever they are, would learn on the same day the same daf of Gemara, is there a more tangible expression for the lofty unification between Kudsha Berich Hu, Oraisa, and Yisrael? Let’s say a Jew travels to America. When he gets there he finds Yidden learning the same daf that he had studied the same day, and he happily joins them….”

Some of the listeners shrugged. Someone in the audience said, “What, now every am-ha’aretz will know Shas?”

And Rav Menachem Ziemba Hy”d, responded, “That’s exactly the point. Someone who knows Shas won’t be an am-ha’aretz anymore.”

While there was some skepticism, later, there was an announcement: “The Knessiah Gedolah in Vienna imposes a moral obligation on every member of Agudas Yisrael to learn at least one daf of Gemara each day. On the first day of Rosh Hashanah 5684, all members of Agudas Yisrael will begin learning Maseches Berachos 2, and so forth each day, one daf, in order.”

A few weeks later, it was related that the Imrei Emes had opened his Maseches Berachos and had begun to learn Daf Yomi on Rosh Hashanah night of 5684, exactly 100 years ago.

And how did it affect the seforim sellers?

That Rosh Hashanah of 1923, there wasn’t a Gemara Berachos to be found in a single seforim store, and people were already purchasing Maseches Shabbos before that, too, would be sold out.

— Menachem Pines

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 978)

Oops! We could not locate your form.