Nest of Golden Eggs

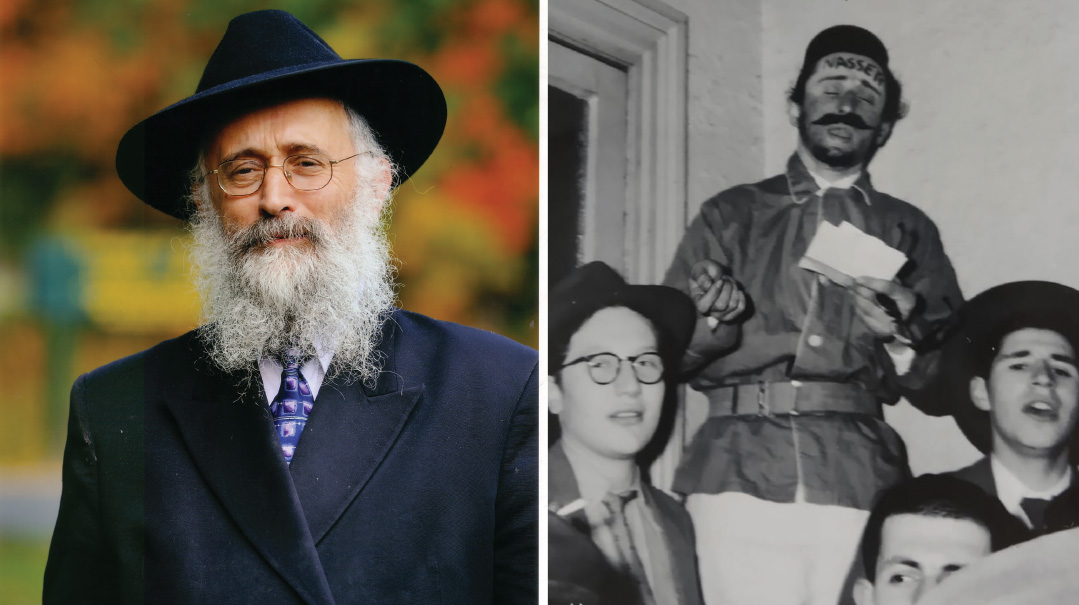

| March 8, 2022Shlomo Simcha and his seven brothers pay musical tribute to their father

Photos: Family archives

For any aspiring singer, creating a music video to accompany a single or new album is a rite of passage on the often-difficult journey toward stardom. And truth be told, music clips are ten-a-penny these days, with many being released each week.

But one recent production stands out, both for its charm and its message. While this wasn’t a debut album for British-born veteran Jewish music star Shlomo Simcha Sufrin (that happened back in 1993 with “That Special Melody”), he and his seven brothers recently released an inspiring and visually stunning video of Yigal Calek’s 1974 Pirchei Yerushalayim classic “Kan Tzipor” about the mitzvah of shiluach hakein, the Torah’s directive to send away the mother bird before taking her young or her eggs. With a technology-generated animated background and motion graphics of mountains, waterfalls, and fields, the voices of all of these musically-talented siblings blend in sweet harmony.

Yet that’s not why eight busy brothers across three continents — involved in business, rabbanus, shlichus, chazzanus, and Jewish music — got together for Shlomo Simcha’s latest production. Shlomo Simcha has released ten solo albums and has collaborated or been featured on at least two dozen more in his nearly three-decades-long career, but this one is different: It’s a family video created as a tribute to their father, Rabbi Mordechai Sufrin a”h, a fiery Yid and legendary mechanech — and someone who had a strong affinity for the special mitzvah of shiluach hakein, often having witnessed miraculous results through it. Rabbi Sufrin passed away five years ago on parshas Ki Seitzei, the sedrah in which the mitzvah appears.

Ultimate Connector

It was Rabbi Sufrin’s first day teaching at King David High School in Manchester. The class was a challenging bunch with a dubious reputation of dispatching their teachers within the first couple of days.

But today, pondered the principal, something seemed different. The usual stream of delinquent pupils making their way to his office hadn’t materialized, and neither had the teacher turned up to quit. What was wrong?

Looking through the classroom window, an unreal scene met his eyes. The students were all sitting crossed legged on their desks, Chumashim in hand, listening in rapt attention to their teacher, Rabbi Sufrin — who was also sitting crossed legged on his desk.

Shaking his head in disbelief, the principal looked forward to speaking with the new recruit during recess, eager to hear his method for winning over the kids and calming the unrest that had become the norm in that classroom.

“I walked in,” Rabbi Sufrin later told the principal, “and the kids were all sitting cross legged on their desks. They were ‘trying it on’ with me on my first day. So I figured I’d play their game by sitting on my desk and teaching them that way.”

Anyone who knew Rabbi Mordechai Sufrin wouldn’t be surprised. He was a larger-than-life personality — a walking encyclopedia, an energetic pubic speaker, and above all, a man for whom chinuch and spreading Yiddishkeit with indefatigable passion, humor, and unending originality was his life’s calling.

Born in Manchester in 1938, Mordechai attended Gateshead Jewish Boarding School followed by the Gateshead yeshivah, where he earned semichah from Rav Leib Gurwicz. During those years, a Russian Yid living in London named Rav Benzion Shemtov used to travel up from London by train (then a six-hour journey each way) to deliver vaadim to bochurim. That influence, coupled with a strong connection with Rabbi Yitzchok Dubov, a Lubavitcher chassid living in Manchester who had learned under the Rebbe Rashab in Lubavitch, helped pave the way for his lifelong connection with Chabad-Lubavitch.

“Rabbi Dubov had a singular influence on our father,” says Rabbi Mendel Sufrin, a rabbi in Leeds, England for over 30 years and the oldest of the brothers (there are also five sisters). “Rabbi Dubov was a tremendous baal mesirus nefesh whose fire for Yiddishkeit was well known.”

After marrying Freyda Klein, a granddaughter of Rav Elya Lopian (as Mordechai Sufrin was a Lubavitcher bochur, some considered it a “mixed marriage,” but Rav Elya himself gave a blessing to the shidduch), the couple settled in Manchester, and Rabbi Sufrin began his teaching career. At the same time, he began working for Lubavitch, running a youth minyan and working his magic on anyone who came within his sphere of influence. He had one motive: to bring people closer to Yiddishkeit and help ensure that boys and girls attended yeshivah and seminary.

Later the family moved to London, where Rabbi Sufrin continued teaching in Lubavitch schools while also becoming involved in various summer camps, eventually launching his own “adventure camp.”

“He was terrific in connecting with the kids,” says Reb Mendel. “Before camp he would change into camp clothes — a Scottish cap and green shirt and trousers. With his ubiquitous sense of humor, he had a tremendous influence on the boys.

“And he was like that at home, too,” Reb Mendel continues. “He was simply an inspirational person to be with, someone who saw Hashem in everything. When we went on an outing, he would stop in the middle of a field, sit us down, and share divrei Torah and stories. He ‘koched’ in teaching and learning Torah, and I quote him almost every time I speak publicly.”

Apart from his teaching career, Reb Mordechai became well known for his passion for informal youth education. There were weekly Melaveh Malkahs in the winter, Friday night mesibahs, and even organized trips to take groups of boys to the US to meet the Lubavitcher Rebbe.

And he didn’t expect anything in return.

“There was a fellow my father taught early on in his career,” says Shlomo Simcha. “Unfortunately, the student drifted away from Yiddishkeit and ended up marrying out. Yet every single year on Erev Yom Kippur, my father called him to wish him a good Yom Tov. He never, ever gave up on a talmid.”

In the Sufrin family, everyone sang and everyone learned nusach by standing next to their father, an accomplished baal tefillah, from the time they were kids

A Bird in the Hand

Outside of his career in the classroom and youth education, Rabbi Sufrin devoted his energies to bringing people close to Hashem and exposing them to the beauty of Yiddishkeit, and somehow the rare mitzvah of shiluach hakein — which the Torah tells us is a segulah for long life, and is a time-tested mitzvah for other yeshuos — took center stage.

“My parents lived their lives with the mantra that Hashem put us in This World to help others — they would drop everything in order to help another Jew,” says his daughter, Rebbetzin Chani Bukiet of Boca Raton, Florida. “So when someone told our father that this mitzvah is a segulah for having children, he went all out to discover everything he could about it, because he saw a new avenue for helping others.”

Rabbi Sufrin had heard about a man in Meah Shearim named Rabbi Don Schwartz who had seen tremendous success with the mitzvah. Every single couple — over a hundred of them — who he had enabled to do the mitzvah had ended up having children. Rabbi Schwartz had even written a sefer on the topic entitled Kan Tzipor, complete with explanatory photos and diagrams on how to carry out the complex mitzvah in a kosher way.

“I was 18 years old and in Israel at the time, and my father called me up and asked me to go to Rabbi Schwartz and get the sefer, which I did,” says Rebbetzin Bukiet. “Not long after, our father came to Israel and visited this man, and had the opportunity to do the mitzvah himself for the first time. And believe it or not, within a week my brother and I both got engaged. After that, he needed no more proof.”

“This happened right before Pesach,” remembers another brother, Rabbi Yisroel Sufrin, of Melbourne, Australia. “He used those tiny dove eggs he brought back from Eretz Yisrael for the Seder and everyone received a tiny piece.”

And thus began yet another side career for Rabbi Sufrin. Boruch Sufrin, who assists his father-in-law as a shaliach at the Shul by the Shore in Long Beach, California, remembers that as a boy, he’d join his father going around public spaces to try spot the nests and identify them as kosher. He enlisted his students as well, and soon there was an entire team of boys scouring the neighborhood and beyond for nests that fit all the conditions for doing the mitzvah.

One of his talmidim once found a nest that was kosher for the mitzvah and Rabbi Sufrin alerted a couple he knew were waiting for children. Gathering his class, they went to the local park where the nest was situated and the husband performed the mitzvah (and the couple subsequently merited a yeshuah).

But the story didn’t end there. Shlomo Simcha relates that when the video was released, “I got a call from a fellow who claimed he was the child who had alerted my father to the location of the nest all those years ago. He told me that at the time, he had been deeply disappointed to have missed out on performing the mitzvah himself, since he was the one who found the nest. When the husband heard this, he felt bad for the child and offered to compensate him with £50, quite a sum in those days. But when my father heard about it, he couldn’t control himself. ‘What? You’ll accept £50 for a mitzvah? Who takes money for a mitzvah?!’”

There was another factor that drove Rabbi Sufrin toward this particular mitzvah, explains Shmuli Sufrin, who lives in Los Angeles where he manages real estate and is involved in kiruv. “Our father was very staunch about the idea that we do mitzvos because that’s what the Eibishter wants of us. A mitzvah binds us to Hashem and we do it regardless of whether we understand it or not. And this mitzvah — let’s face it — it’s difficult to understand. You shoo away the mother to take her eggs? That appears mean and cruel. So, in a way, by championing this mitzvah he stuck up for Hashem and His Torah. He knew that if Hashem mandated it, it had to be the right thing, which made it even more meaningful to him. Our father was like a diplomat representing Hashem and defending the eternal truth of His Torah.”

Throughout his career of teaching and spreading Torah, Rabbi Mordechai Sufrin wasn’t afraid to animate Yiddishkeit and make it real in a way he felt was genuine

Where He Wants You

Rabbi Sufrin’s message of unconditional ahavas Yisrael, seeing the positive in every Yid no matter what, was a legacy he bequeathed to his children.

“The last vort I heard him say,” recounts Dovid, a businessman in Crown Heights, “is that when the Yidden crossed the Yam Suf, it split into 12 channels. But every Jew could see the person in the next channel. Why? To teach us that there are many ways to serve Hashem and there are many different approaches. The trick is to see through all the tunnels, past the differences, and to understand that we can learn from everyone. That’s why Hashem made the walls out of water.”

A Yid is a Yid is a Yid, Rabbi Sufrin would say. “And because of that,” says Dovid, “when we were growing up, he’d take us to daven in all sorts of shuls, not just Lubavitch. He brought us up in a way that we’re part of one Klal Yisrael, not different groups.”

That’s why, on Friday nights, the Sufrins would daven in a litvishe shul in Golders Green — Bridge Lane Beis Hamedrash — which was also attended by Yigal Calek and his boys. They shared a table with the musical Sufrins, singing Kabbalas Shabbos together and forging a connection through the common language of music.

“Our father didn’t want me to join Yigal’s choir,” says Shlomo Simcha, “but I made sure to sit right next to him in shul. Our families became close, and music was a big binder, as it was very much part of our lives growing up.”

In the Sufrin family, everyone sang, everyone knew nusach, everyone leined. Shabbos, says Shlomo Simcha, was amazing. Rabbi Sufrin was a baal tefillah and the boys all learned nusach by standing next to him at the amud.

And for Shlomo Simcha, those early years eventually pushed him to the studio. In 1990, when he was learning in kollel and serving as a chazzan in a shul in Montreal after his marriage, he was discovered by a local wedding band leader who put him in contact with someone from Williamsburg who was recording a series of children’s tapes. Those tapes are long forgotten, but they somehow caught the attention of Mendy Werdyger, MBD’s brother and owner of Aderet Records. Werdyger introduced him to producer Sheya Mendlowitz, and the rest, as they say, is history. Around that time, Shlomo Simcha moved to Toronto, where he became a popular chazzan and began to collaborate with his long-time friend Abie Rotenberg on the Aish album series (they’re up to Aish 3). Last year he moved from Toronto to Boca Raton, Florida, near his sister and brother-in-law, shluchim Rabbi Zalman and Chani Bukiet.

The Song Still Plays

The release of the Sufrin brothers’ music video comes at a time when Yigal Calek’s own music is experiencing a surge of renewed interest and popularity. A widely-viewed Chanukah 2021 London School of Jewish Song reunion shows an elderly yet beaming Yigal, outsized personality clearly on display as he presides over a journey down memory lane, surrounded by his beloved choir boys — many of them now zeides themselves. The men sang many memorable golden oldies with those same harmonies, intonations and kneitches Yigal made popular so many decades ago.

Shlomo Simcha says it’s not surprising that “Kan Tzipor” was his father’s favorite song. “As I see it, there was a certain synergy between Yigals’s music and our father’s life and ideals. Yigal’s songs were fresh, full of chiddush, melodies that were his own interpretation of the words. He put out a certain style of music because he believed it expressed the words best, regardless of whether he thought there was an audience for that. Our father was like that too: Through his career of teaching and spreading a love for Torah and mitzvos, he animated Yiddishkeit and made it real in a way that he felt was genuine.”

Although the simpler piano and guitar arrangements on the original “Kan Tzipor” can’t compare with the rich orchestral sound on the Sufrin brothers’ version, there’s a certain sense of nostalgia in the production.

Although according to Moshe Sufrin, who lives in London, it goes further than just nostalgia. “There is a certain yearning for the simplicity and authenticity of a bygone time,” he says. “That’s the feedback we’re getting. It has an enduring appeal that people want to connect to.”

Shlomo Simcha believes it’s not about the music or the voices or the production. “It’s the toichen of the song that carries a special magic. When our father passed away five years ago, before the levayah began when the mitah was still in the house, we all sat round and sang that song to our father. Behind us on the shelf, lined up in a row, were a collection of all the eggs our father had amassed over the years from doing the mitzvah.”

With a father so trailblazing and inspirational, it’s no wonder his 13 children are dedicated to perpetuating his legacy.

“Our father had this incredible knack for being able to get through to people, to really communicate,” says Shlomo Simcha. “And although we’re all in different fields, that’s how we all communicate — some through teaching, some through music, some through rabbanus, and some through shlichus. For me, I try to communicate through the universal language of music. I believe people should walk out of a kumzitz on a higher level than they walked in, and that’s where I try to make my impact felt and get through to people.”

Another sibling helps run the Keren Menachem and Keren Chanah fund established by their father, foundations that assist with covering tuition fees of boys and girls whose families can’t afford yeshivah and seminaries.

Mrs. Chavi Spalter, the oldest child, says it’s all about caring about people — and always with joy. “That’s how we were raised. In our house there was always one corner of fun. At the same time that our parents gave us the importance and depth of life in a very real way, it was not somber or austere. It was always positive, especially with my father’s fantastic sense of humor.”

Mrs. Sufrin ybl”ch was involved in the chinuch of her children in her own hands-on, original way. “Even with a busy household of 13 kids, my mother would ensure that each of us had five minutes alone with her when we returned from school, and another five minutes before bed,” recalls Shlomo Simcha.

He mentions another example of his mother’s wise approach to ensuring each child had what they needed. “In 1980, there was a Yigal Calek concert in Wembley, together with this new singer named Avraham Fried, and I so badly wanted to go. With a household as busy as ours, this wasn’t usually something my mother had time for. But she knew how badly I wanted it, so she made the time and took me. It was clearly a precursor of things to come, because I remember saying to my mother, ‘one day I’ll be up there on stage too.’”

Reb Yisroel, from Melbourne, relates what a certain man told him recently. “Our father was once in Reb Chuna’s shul in Golders Green when he met a fellow he vaguely knew. ‘How is your zeide doing?’ he asked. ‘He passed away,’ responded the man. ‘Oy, and how is your father?’ our father continued. ‘He passed away too,’ said the man, obviously in pain. At that point, our father stopped the questions. But the man later told us that at the time he was in deep despair and became a recluse, only leaving his home to go to shul to say Kaddish. ‘The only person who would call me up to see how I was doing and invite me over for a chat and a l’chayim was your father,’ he told us. ‘I didn’t know him well, but he saw I was struggling.’

“That was our father’s essence — his ability to connect — and that’s what we’re trying to do too, each in our way.”

Green screen technology in London and the US. Today, everyone can sing together, even if they’re continents apart

Across the Divide

With the family spread out across the world — from the west and east coasts of the US, across the UK to Israel and Australia, finding a time to interview all of them together was its own challenge. But the minor challenges of assembling the group for a Zoom call pales in comparison to the logistical efforts required by the brothers to arranging for the recording of the audio, and then a video clip.

“It took over a year to get the project going,” says Shlomo Simcha. “Getting the vocals done was the easy part. The real challenge was the visual part. But thanks to green screen technology, even though the clip was shot at different locations, we were able to piece it together and produce the clip. The fact that we were doing it for our father gave us the impetus to keep going, despite the considerable challenges involved.”

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 902)

Oops! We could not locate your form.