Nachum Sparks and the Mystery of the Missing Menorahs

| November 25, 2025Even a wheelchair can't stop him

Illustrated by Esti Saposh

Chapter 1

Thursday morning, December 11th

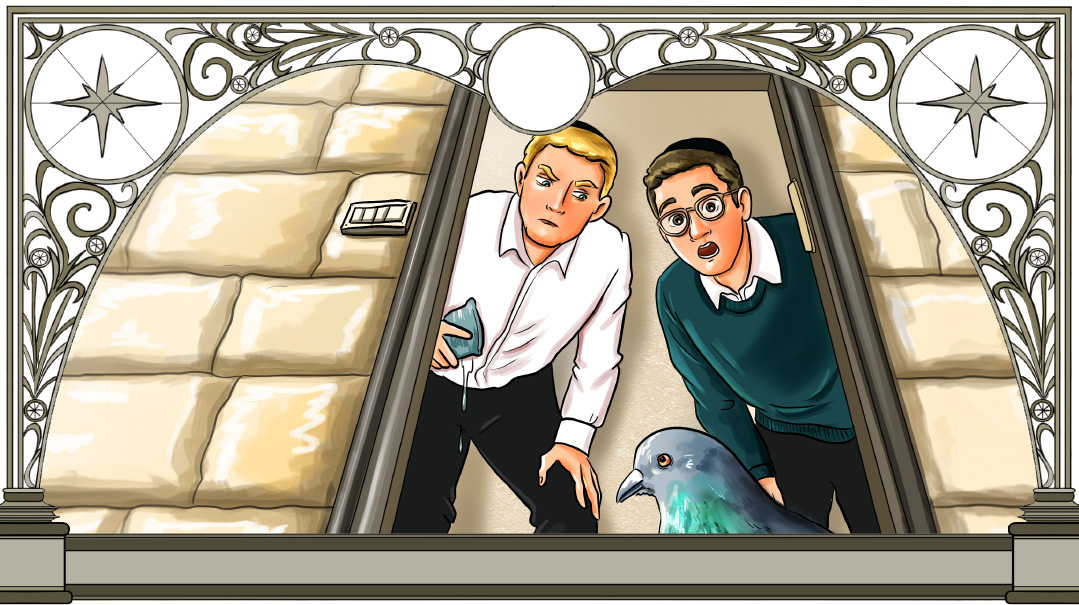

“N

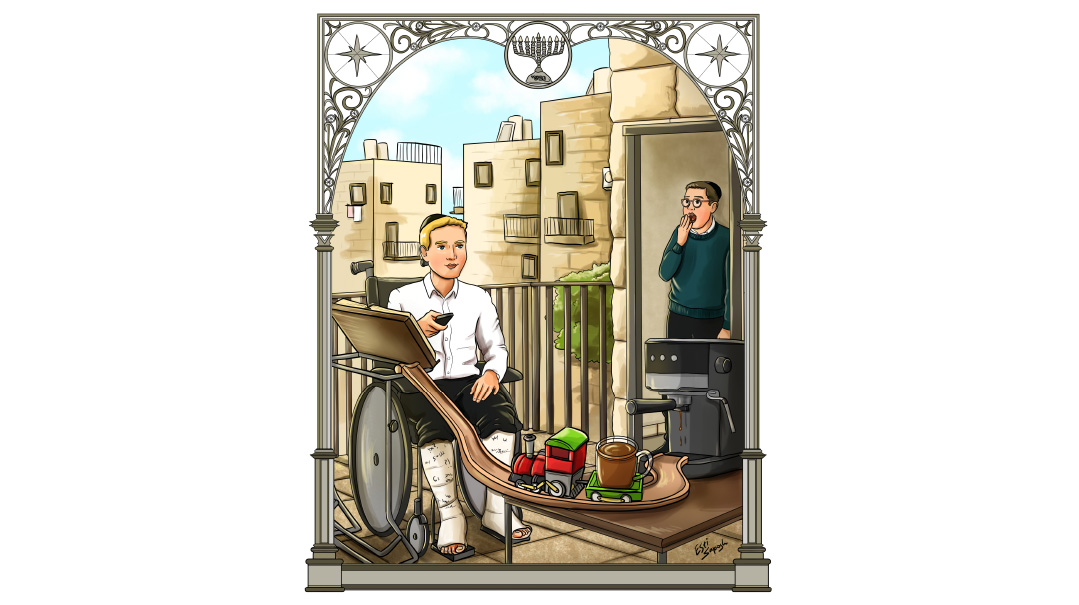

ice job on the eggs, Rosen, but they’re in dire need of salt.” The back of Nachum’s blond head called to me as he sat in his wheelchair on our mirpeset. I could see his bowl and fork sitting on his shtender, untouched.

“You haven’t tried them yet,” I called back.

“Yes, but I can see that they’re not salted enough.” He speared an egg globule and turned to point it at my face. “Sodium causes egg proteins to uncoil and lose their structure, so salted eggs have a deeper and more saturated color. These are far too pale, Rosen. Grab me the salt shaker from the kitchen. Oh, and while you’re there, can I trouble you for the popcorn?”

“The popcorn’s from Shabbos. Today’s Thursday.”

“Your point, Rosen? Hurry, if you can.”

I looked down at my roommate. My expression must have betrayed my agitation.

“Please,” he added sweetly, his hands beneath his chin.

“Fine,” I exhaled. Back to the kitchen I went, mentally counting the days until Nachum finally gets his casts off.

You might think that Nachum got injured on the job — after all, he’s known for his run-ins with the Russian mafia and a crime ring in Jenin (see episodes #5 and #27, respectively, of our podcast). But, no… leave it to Nachum Sparks, Jerusalem’s most famous detective, to break both his legs trying to take down our menorahs from the machsan. If only he had labeled the boxes normally as I had suggested, instead of using simanim from Shulchan Aruch-Orach Chayim (Pesach stuff = 451; Chanukah = 670; Winter clothing = 114), he might not have had to shift so many boxes around until he lost his footing and fell off the ladder. But alas, no one ever listens to me around here. Ten more days, I thought to myself with a sigh.

“Hurry, Rosen! It’s almost starting!” Nachum yelled from outside.

I raced back with the salt and popcorn. “What’s almost starting?”

“Morning in Jerusalem.” Nachum gestured to an empty Keter chair.

“I’m not following,” I said, taking a seat.

“Look at the mirpesets, Rosen. Tell me there isn’t something exhilarating about it — the entire city starting their day at the same time.” Glancing at his watch, Nachum pointed with a finger like a conductor’s baton to the building directly in front of us. “Cue the chazzan.” Suddenly, a deep baritone voice sang out a vocal exercise. “Like clockwork,” said Nachum. “That’s the famous Chazzan Neuman. He davens at Shtilerman’s. He practices every morning. In five minutes, Mr. Friedman, two buildings to the left, one floor below” — his finger traveled across the skyline — “will begin his piano lessons. So far, it’s been Bach, Prelude no. 1 in C Minor… Now, Rosen, put out your hand.” From above, a soapy droplet landed in the center of my palm. “That’s Mrs. Pessin sponja-ing, as she does every Thursday morning l’kavod Shabbos. Her married kids must be coming, as you can already hear the clink of china; she uses chad pa’ami when it’s just her and her husband. Ahh… but this is really the thrill…” Nachum leaned forward in his wheelchair. “Will Naftali Freudlich make his hasa’ah this morning?”

“Who in the world is Naftali Freudlich?”

Nachum pointed with a popcorn kernel to the mirpeset in the building diagonally across from ours, three flights down.

“The American family that lives in that apartment. The father, Reb Gamliel, learns in the Mir — I’ve seen him take the Mir bus with Reb Elimelech Gershonowitz in the mornings. The mother works the morning shift at Shaare Zedek — she gets picked up by a hospital van — so that leaves him to get the kids out on time. Naftali’s turning four on Chanukah; there’s a wrapped Bimba on the mirpeset that’s a combined birthday and Chanukah gift. Poor kid. He’s missed the hasa’ah twice this week. There,” he pointed to a navy-blue van wending its way from the opposite side of town. “You can see the hasa’ah on its way. Will he make it today, Rosen? You tell me. Frankly, I’m scared to look.”

I squinted at the scene behind the Freudlichs’ glass sliding doors: a bowl of cornflakes flying through the air, a baby crying, and a red-headed kid having a tantrum on the floor. “I don’t find my other boot,” the boy wailed. Reb Gamliel was blinking at his son vacantly, like a computer that has crashed because of too many open tabs.

I glanced over at my roommate. He was looking in the same direction as me, but he had his fingers over his eyes.

“I don’t find my boot,” Nachum repeated. “Naftali’s just started Hebrew gan this year, and we can infer that he’s already thinking in Hebrew because with two American parents, shouldn’t he have said, ‘I can’t find my boot?’ Smart kid. But what do we do about his boot? I give it 30 more seconds before Reb Gamliel calls his wife for help.”

It only took five. Nachum and I watched as Reb Gamliel pulled out his phone and began punching in numbers. He nodded slowly with the phone to his ear and then conveyed something to his son. “But I don’t want to wear my Shabbos shoes!” the boy began to scream.

“Wait a minute,” said Nachum. “I know where the boot is.”

“No way,” I replied, shaking my head. “I don’t believe you.”

“I do. He was wearing them yesterday afternoon when he was pretending to be Sammy HaKabai [Editor’s note: translation – Sammy the Fireman]. It must be in the toy bin. We need to tell them. But how?”

“I don’t know, Nachum, this is crazy. You don’t even know these people, do you?”

“Focus, Rosen. The hasa’ah will be there in a minute. What should we do?”

“Yell?”

“Ok, on the count of three, scream as loudly as you can.”

Nachum and I screamed “toy bin” at the top of our lungs. Reb Gamliel looked momentarily in our direction but I’m guessing we were drowned out by the baby’s wailing and Naftali’s tantrum.

By now, the blue of the van was streaking across the street in front of us.

“Let’s try it again,” my friend commanded. This time, we screamed so loudly that our breath was a visible column of condensation on that cold December morning; this time, Reb Gamliel jerked his head up as if waking from a spell.

“He probably thinks it was a bas kol,” my roommate said, grinning.

“You know, Sparks,” I lamented, “I used to be normal once… before I met you.”

Nachum crunched loudly on a handful of popcorn. “That depends on how you define normal, Rosen. And admit it,” he handed me the bag, “you know you wouldn’t want it any other way.”

I chewed on the stale popcorn as I watched Reb Gamliel walk over to the white cabinets on the back wall of his living room and pull out a bin of haphazardly stacked toys. When he overturned its contents, the red-headed boy jumped up, held up his boot like a trophy, and dashed toward the door.

Beep, beep went the van from below, and out of the lobby doors bounded the grinning almost-four-year-old. Nachum and I cheered as the van whisked him off to cheder.

“Well done, Rosen,” my roommate said, clapping me on the shoulder, “but my nerves are totally shot. This calls for a coffee. You interested?” I shook my head no as Nachum picked up a small remote on the shtender next to his wheelchair and clicked a button with his thumb. Suddenly, the coffee machine in the corner of our mirpeset leapt to life, sending a stream of steaming, brown liquid down into a waiting mug. The mug, I soon realized with astonishment, was resting on a model train car I had seen the Gershonowitz kids playing with in our building lobby. The train car traveled along its tracks to deliver the coffee to Nachum’s feet.

“You could just wheel yourself over to the machine, Nachum,” I pointed out sensibly.

“And willingly interrupt my learning every time I need a coffee?” he said, sounding incredulous.

As Nachum sipped his beloved Costa, I surveyed the rest of the mirpeset: the coffee-train station in the corner with the electrical outlet, around 12 boxes of Krembos along the wall (to sustain the height of the marshmallow filling, Nachum insisted, the snacks are best stored in the cold), a heating lamp, a shtender, towers of canned pickles and olives, Nachum’s viola, and an entire bookshelf of seforim.

It had seemed like a good idea for a homebound Nachum to relocate to the mirpeset for the daytime hours; he was going stir-crazy in the apartment, and I thought the fresh air would do him good. What I had not anticipated was that he would turn our mirpeset into his personal beis-medrash-slash-man-cave, nor that he would unleash his inimitable powers of deduction on the poor, unsuspecting residents of all Jerusalem buildings visible from his wheelchair.

“Nachum, don’t you think…?”

Two blue eyes shot up from above a coffee mug. I hesitated. How to put it delicately?

“Does it seem a little….?”

“Yes?”

“Isn’t it a little…?”

Nachum began pointing his train remote at me. “Is there a way to increase the playback speed of your thoughts?”

I sighed. “Fine. I’ll just say it then. Don’t you think it’s a little invasive to be spying on random people without their knowledge or permission?”

Nachum lowered his mug. He tapped the handle with each new point: “Firstly, I don’t know anything more about people than they choose to broadcast through their open windows. Secondly, I use that knowledge only to help. And thirdly — perhaps most importantly, Rosen — is the fact that a neighborhood runs according to a certain beat, and any good detective worth his pay has to have an ear for it. Crime, Rosen, is by definition, a discordant note in the natural routine and rhythms of city life. Feel free to quote me as such on our Substack.”

I tried committing those last few lines to memory as Nachum tilted his head back and took another long sip of coffee. “Speaking of a break from routine” — he looked me straight in the eyes — “Rosen, I have a huge favor to ask of you.”

Uh-oh, I thought to myself. This did not sound good.

N

achum pulled a neat stack of index cards from his pockets. I took one look and knew they were his famous bechinah flashcards, with the whole shakla v’tarya of each daf and the shittos of the Rishonim and Acharonim all condensed onto a single notecard in Nachum’s neat, blue-penned scrawl.

(He’s written them for a bunch of different masechtos, and there are guys in yeshivah who will pay hefty sums to borrow them before a big bechinah. There’s even this first-year bochur — the entrepreneurial type — who’s trying to convince Nachum to patent and sell them under the name SparksNotes©.)

“I have the entire masechta on Monday’s bechinah prepared for you,” Nachum said in a disconcertingly sweet voice. He extended the cards to me.

“What’s the favor?” I asked, letting his hand dangle mid-air.

It came out all at once: “Elimelech Gershonowitz and his wife were waiting for months to get an appointment to renew their passports at the American embassy. A couple of weeks ago, a slot opened up for them for today, but it’s the same day as baby Sruly’s Tipat Chalav appointment. You know about the measles outbreak in Jerusalem, right, Rosen? So of course they didn’t want to push off his shots. Reb Elimelech was telling me all this on the walk back from Shacharis one morning, and I offered to take the baby instead. He said he had to discuss it with his wife first but I guess they were really desperate because he came back saying, ein breirah, they would take me up on my offer, but I obviously can’t take Sruly anymore…” He looked down sadly at his encased legs.

“So you’re asking me to take him instead?” I hoped I sounded as outraged as I felt. Nachum nodded. “But I’m not his legal guardian.”

“Neither am I.”

“Is it legal for a non-guardian to bring a baby for a shot?”

“Asks the man who had me have Myron run a full, Mossad-level background check on a shidduch prospect.”

“I needed to know if she was related to my sho’el u’meishiv! They have the same last name, and I couldn’t ask him but I also couldn’t not know.” Even when I repeated it to Nachum now, it sounded perfectly reasonable to my ears.

“They’re first cousins, by the way.”

“Really? How long have you known that for?”

A little smile played on Nachum’s lips. “Oh, just a week or so.”

“A week? Are you serious? Why didn’t you tell me?”

“I don’t know… it slipped my mind.”

“Nachum, if I didn’t know better” — my voice was rising despite my efforts to keep it level — “I’d say that you’re sabotaging my shidduchim because you’re scared to lose me as a roommate.”

To my supreme annoyance, Nachum was all calm, slow-blinking innocence. “You do such a good job sabotaging it yourself, Rosen, that there’s precious little left—”

“Regardless, I’m not taking Sruly to Tipat Chalav.”

I watched as the cards in Nachum’s hands began slowly retracting. I saw my bechinah grade drop with each centimeter they traveled back toward his wheelchair.

“I’ll miss seder and Minchah,” I protested.

“I already spoke to your chavrusa. You have a break during the appointment, and you can catch Minchah at Shtilermans and be back in time for second seder.”

“You spoke to my chavrusa?” I exclaimed. Speaking of invasive behavior…

“Yes, and I mapped out a timetable for you.” He handed me a post-it note. “It’s really all worked out.”

“Except for the fact that I don’t know how to take care of babies.”

“You did almost drop Mrs. Pessin’s granddaughter on Shavuos but you’ve come a long way since then, Rosen. You’ll be great. And I’ll talk you through it. You won’t need to lie. Just walk in with confidence and everyone will assume you’re the father.” He handed me an envelope. “Just in case, I also prepared a document signed by an attorney that the Gershonowitzes give you permission to bring him in.”

So that’s how I found myself making my way after shiur to Sruly Gershonowitz’s ma’on and from there, baby in tow, to Tipat Chalav.

My phone buzzed in my pocket as I approached the clinic.

“You have his pinkass, right?” my roommate asked.

“His pink what?”

“His pinkass,” my roommate repeated, enunciating each syllable as if speaking to a toddler.

“Oh, you mean his immunization records? Yeah, yeah, I have it.”

“Okay, good. I’m staying on the line to walk you through it. Go down the staircase to your right.” I nestled the phone in my ear as I hoisted Sruly up in his carriage and carried it down the steps. “Go through the gray doors in front of you.”

“They’re locked.”

“Not the clothing gemach doors, Rosen. The other ones.”

“Oh, okay. Got it. I’m in.”

“Excellent, now tell me what you see.”

“Babies.”

“Honestly, Rosen. I’m trying to help you make Minchah. Can you give me a little more information?”

“All I see are lots and lots of babies.”

“What else?”

“What else do you want from me? Babies and… strollers?”

“We need to figure out which nurse you should see. Now tell me, is there a mat on the floor?”

“A mat? Hmm, no.”

“Ok, so that means the PT isn’t there. That’s not good. That means everyone is there to see the nurses. Describe for me how many families are waiting by each door.”

“Four” — I squinted at the placard by the door — “are waiting for a nurse named Ruti. There are about six sitting on the other side of the room waiting for” — I squinted again — “Tziporah.”

“Okay, how many of them are newborns? Newborns are quicker appointments, they come for weigh-ins but not for shots.”

“How do I tell if it’s a newborn?”

“Are you serious?”

“Yeah, like they’re all in diapers… does that make them all newborn?”

There was a pause on the other end. “Tell me, Rosen — I’m genuinely curious — is your astonishing level of ignorance an American thing, or is it a you thing?”

I chose to ignore his question. “So how can I tell if they’re newborn?” I persisted.

“Look at their eyes and skin color. Newborns are much redder. They also will have semi-closed eyes or, if the eyes are open, an unfocused gaze.”

“Okay, so then I’d say two out of four waiting by Ruti are newborns, and four out of six waiting for Tziporah.”

“Excellent. Now can you look inside the rooms? What do you see?”

“I see a baby on a scale in Ruti’s room.”

“Okay, now this is critical, Rosen: Is the baby dressed?”

“No. Wait… now I see that a baby is going on a scale in Tziporah’s room too. This baby’s dressed.”

“Aha! Excellent, Rosen. So Ruti is makpid to weigh the baby without clothing, whereas Tziporah keeps the baby dressed and just deducts a few grams from the weight. It takes about two minutes for a mother to undress and re-dress a baby. A father, generally speaking, takes more like seven. It would take you about ten. So that time difference needs to be factored in. Additionally, if Sruly is weighed without his winter fleece and his diaper, he’ll weigh about a kilo less, which makes it more likely the nurse will give you a lecture about him not weighing enough. That would add another four minutes, on average. I also don’t want to run the risk that your incompetent answers to questions about his feeding schedule will expose the fact that you’re not the real father… No, no, we can’t afford a lecture about Sruly’s weight. Okay, Rosen, I’m deciding on Tziporah.”

I looked down at Sruly, who took his toe out of his mouth to give me a huge, gummy grin.

“We’re going to move over to Tziporah’s line,” I informed him as I wheeled the stroller over to the opposite side of the room.

“Oh, and one more thing, Rosen” — was it the poor reception or did Nachum’s voice get softer? — “you’ll remember to say a perek of Tehillim when the needle goes in? And you’ll give him his dummy — that’s his pacifier, Rosen — as soon as it’s over?”

I assured Nachum that I would.

As he predicted, Tziporah’s line moved far more quickly than Ruti’s, and I only had a chance to go through Nachum’s bechinah flashcards one-and-a-half times before it was our turn. All in all, the appointment went better than I expected: I did not drop the baby once (probably because I didn’t have to change him), and Sruly cried for only a few seconds after his shot. He looked at me as I wheeled him out with his blue, smiling eyes. (My roommate’s on to something with his “future Nachum Sparks,” I thought to myself. This baby’s a keeper.)

After safely depositing Sruly back at his ma’on, I walked the short distance to Shtilerman’s. I hadn’t noticed how cold I was until I came inside and was hit by a soothing gust of warm air.

The shtibel was buzzing: gas technicians were working on the boiler by the front hall closet, and a very heated debate about the day’s daf was underway.

Shtilerman’s was the type of shtibel where people noticed a new or less-familiar face; within a few minutes, Reb Yoel Laufer, the gabbai, was shaking my hand and giving me a hearty shalom aleichem.

First, he wanted to know what I was learning. We discussed this for a bit before Reb Yoel asked, “And how’s that illuyishe friend of yours? The one that’s eppes a… a… how do you say it? … a detective. I haven’t seen him in a while.”

I explained that he was largely homebound because of two broken legs.

“Please send him my refuah sheleimah,” Reb Yoel continued. “My nephew was by us for Shabbos and he was going on and on about how much he loves the …ich veis… the broadcast that you two put out.”

“Podcast?” I offered.

“Yes, yes. The podcast. That was the word he used. Anyway, we’ll be having a special shiur on the Sfas Emes during Chanukah if you boys want to come. Before Minchah each day. I already have our menorah out,” he finished proudly, gesturing to the beautiful silver piece by the shtibel’s southeast window.

Someone klopped on the bimah, and Minchah began.

When I got back from second seder, Nachum was hunched over a giant placard and was making broad marker strokes.

“Welcome back, Rosen,” he said without looking up. “I’m preparing our dirah’s Chanukah programming.”

“We have programming?” I asked.

“Yes, and obviously, the most important piece is the limud. I’m thinking we do a masechta of Nashim each night and then stay up all night of Zos Chanukah to review all seven masechtos. How does that sound?”

I thought it sounded a bit crazy, to be honest, but Nachum was looking at me with such earnest excitement, I could only say, “I hear. Sounds good. Also, what’s with the arts and crafts?”

“It’s a chart, Rosen. A sufganiyah chart.”

“What’s a sufganiyah chart?”

“Well, I want to put an end to our longstanding debate about which Israeli bakery makes the best sufganiyot. So I’ve listed eight contenders in the left-most column and then in each of these boxes we rate the doughnut — 1 being the lowest, 5 being the highest — on three key criteria: creaminess of filling, moistness of crumb, and filling-to-doughnut ratio. We’ll sample a different one each night, give our ratings, average our composites together, and thereby determine, clearly and scientifically, which doughnut is best.”

“I like your idea of eating from a different bakery each night, but can’t we just eat and enjoy without the ratings and science part?”

Nachum shook his head slowly. “I don’t understand you, Rosen. That is precisely the most enjoyable part.”

Well, I thought, we’ll just have to agree to disagree on that. Suddenly, I heard the whir of a motorcycle.

Nachum didn’t look up from his chart. “Tell me, Rosen, is the motorcycle being driven by a Wolt delivery guy?”

I peered over our soragim. “Yes.”

“He’s delivering to the newlywed couple in the Rubanowitz’s yechidah. Momentarily, you’ll see him with a Big Apple pizza box.”

“How do you know?”

“At this time each night, the chassan orders a Wolt dinner and eats it quickly on the mirpeset. The kallah is still learning to cook and he doesn’t want to insult her. On fleishig nights, he orders from Flame, but inhale, Rosen, and you can tell that tonight was dairy. Burnt lasagna, to be precise, and on dairy nights, he orders Big Apple pizza.”

“Remarkable,” I said.

“Obvious,” my roommate countered. “What’s less obvious is why” — Nachum put down his marker and looked up at the night sky — “there are those blinking red lights.”

I followed the direction of Nachum’s eyes and spotted them too. They were getting bigger and brighter.

“It’s a drone,” Nachum said gravely, “and if I’m not mistaken, which is almost always the case, it’s heading straight for our mirpeset.”

To be continued…

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 1088)

Oops! We could not locate your form.