My Son the Doctor

| September 26, 2023Decades ago, smart Jewish boys had to bang on closed doors — or slip through a narrow crack — to become “My Son the Doctor.”

The first Jew ever to be elected President of the United States calls his mother and shares the good news, to which she replies, “So?”

He tells her she will have to attend his inauguration, to which her response is, “I don’t have a thing to wear.”

“Don’t worry, I’ll get you a dress,” the president-elect tells her.

“How will I get there?” his mother asks.

“I’ll send a limousine for you.”

At the inauguration, the First Mama is sitting among all the dignitaries as her son is sworn in. She looks around, and then in a loud voice announces to the assembled VIPs, “See that fellow up there being sworn in? His brother is a doctor.”

This well-known joke, is representative of an entire genre of 20th century humor and emblematic of the cultural phenomenon of “My Son the Doctor.” It’s a concept that not only shaped medical practices across America, but also inspired plenty of Borscht Belt humor — and even a board game.

Closed Doors

Decades ago, smart Jewish boys had to bang on closed doors — or slip through a narrow crack — to become “My Son the Doctor.” A Jewish Telegraphic Agency exposé from 1935 titled “Jewish Doctors Seen Too Numerous,” reported that Dr. Samuel J. Kopetzky, former president of the New York County Medical Society, “delivered a defense of racial and religious quotas in American medical schools. He said, in effect, that Jewish medical students should be limited in number to the proportion of Jews to the American population.”

That same article declares, “Of late years, all surveys indicate, 17 to 20 percent of medical school registration has been Jewish.”

Dr. Kopetzky’s defense of anti-Jewish quotas was, in an ironic twist, based on an assumption that only Jews would want to be treated by Jewish physicians.

Professor Dan Oren, in Joining the Club: A History of Jews and Yale (1985), for example, quotes Dean Milton Charles Winternitz of Yale Medical School as instructing his admissions committee, “Never admit more than five Jews, take only two Italian Catholics, and take no blacks at all.” Yale University only dropped its overall quota for Jews, pegged at ten percent, in the early 1960s, according to Professor Oren.

It’s been decades since America’s medical school opened their doors wide to Jews, but the issue remains a timely one. As reported by the Times of Israel in June of this year, “Harvard’s 20th-century anti-Semitic Jewish quotas were a key part of the Supreme Court’s decision (6-3) to gut affirmative action.”

American Dream

The increase in Jewish interest in medicine, to disproportionate numbers at the turn of the 20th century, has been linked to the huge influx of Russian Jewish immigrants from 1880 to 1914, when two million Russian Jews joined an existing US Jewish population of 400,000. In fact, from the late 1800s until 1930, Jews comprised 50 percent of all immigrants to America.

In a 1969 American Sociological Review analysis, “My Son the Doctor: Aspects of Mobility among American Jews,” Mariam K. Slater reviews the various factors underpinning the high percentage of Jewish professionals in medicine and other fields. She attributes the phenomenon to Jews’ traditional high regard for learning and to the high remuneration of the professional occupations — e.g., accountants, lawyers, and doctors.

Game On

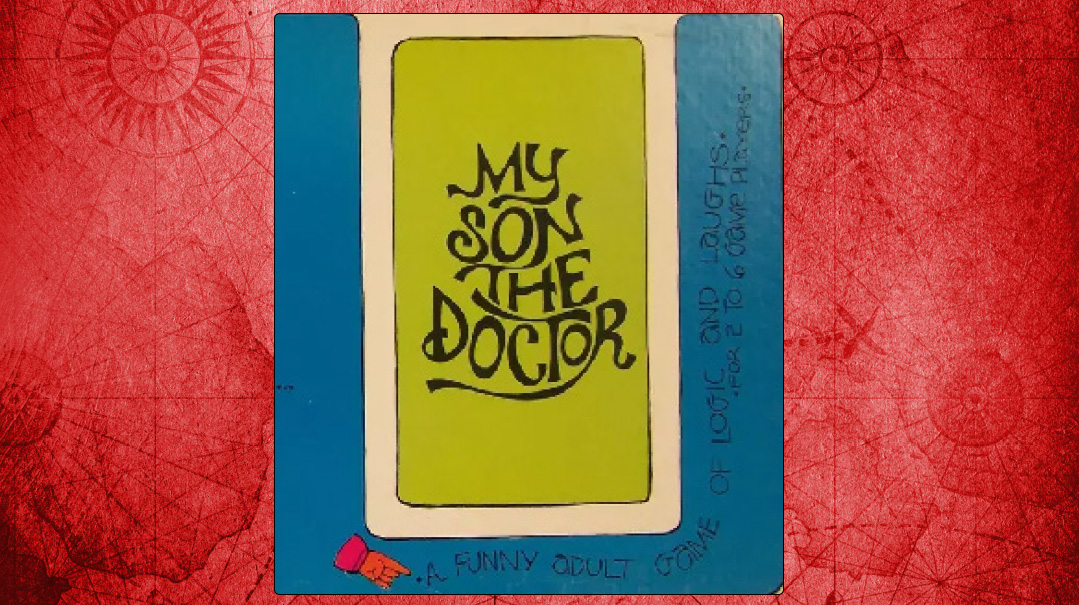

In 1968, What-Cha-Ma-Call-It Games released a board game named My Son the Doctor, with the following description and rules: “Want to make Mama proud? Become My Son the Doctor. Let Mama impress her friends.... All it takes is a little luck... a little concentration, and knowing when to keep your mouth shut!”

Drawing on traditional Jewish humor, this game has players begin at home with Mama, and through the course of the game pick up “Odd Jobs” and “Tools of the Trade.” Once the player gets to his target profession after acquiring four good tools for that trade, he wins!

Borscht Beliefs

The origins of the phrase “My Son the Doctor” are not so clear, but it appears to have originated in Jewish humor, becoming part and parcel of a secular American Jewish ethos.

In 1962, American Jewish entertainer and parodist Allan Sherman released his first album, My Son, the Folk Singer, which peaked at number one on the Billboard album chart. Sherman followed up a year later with My Son, the Celebrity, and My Son, the Nut, both also earning number one album status, with the latter featuring the hit single “Hello Muddah, Hello Fadduh.” It has been speculated that the iconic phrase “My Son the Doctor” is a riff on the titles of Sherman’s albums.

Looking Forward

Some more recent studies suggest that Jews continue to be overrepresented in the medical field today.

A 2005 Journal of General Internal Medicine survey on the religious characteristics of US physicians showed that 14.1 percent identified as Jewish (compared to Jews accounting for 1.9 percent of the total US population).

A 2011 study (Lynn, R., “The chosen people: A study of Jewish intelligence and achievement,” Augusta, GA: Washington Summit Publishers) measured “achievement quotients.” An achievement quotient of 3, as defined by the study, means that Jews are three times more likely to have achieved professional accreditation than their proportion to the general population would predict. Overall, the study showed: “There is a large overrepresentation of Jews in the professions, with an achievement quotient of 5.8 for psychiatrists, 4.0 for dentists, 3.8 for mathematicians, 3.7 for doctors, 3.4 for writers, 3.3 for lawyers, and 1.7 for architects.”

The Muslims coined the term “People of the Book” for Jews (though it included Christians as well). Perhaps one can say that for a period of time in 20th-century America, that title could be paraphrased as the “People of the Medical Book.”

Ari Lieberman is author of The Emperors and the Jews, and hosts the Sparks of History podcast on the interface of Jewish and world history, which features prominent rabbis, Pulitzer Prize winning authors, and award-winning historians.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 980)

Oops! We could not locate your form.