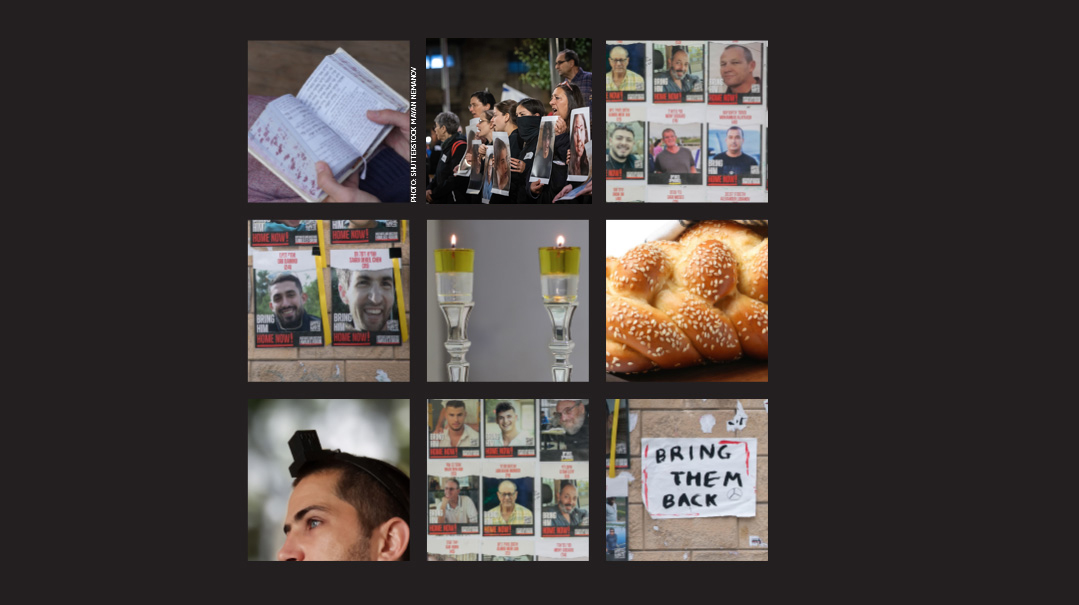

My Son Is in the East

| February 27, 2024Parents of lone soldiers open a window to their fears, prayers, and pride

As the war drags on, our fervent prayers have lost some of their urgency. But for those with children on the front, the war and worry are ever present — and for parents of lone soldiers, whose fear is compounded by their distance, those emotions can be even more overwhelming. Family First speaks with parents of lone soldiers, both religious and non-religious, to give a window into what it means to have a child at the front

“I’m fine, going out for an assignment rn, I love you all, send my love to everyone. It was a scary day, but I’m glad I had the zechut to help protect am yisrael. I will speak to you when I can.”

That was the text Chava saw when she turned on her phone after Yom Tov on October 8. It was from her son Yaakov, a lone soldier, who has been in and out of Gaza since the beginning of the conflict.

Around December of his post-high school year in a yeshivah in Eretz Yisrael, Yaakov, the oldest of Chava’s three children, expressed a desire to join the IDF. “I told him no, he needs to finish the year, and then go to college,” says Chava. But even though he was a good son and listened to his mother, returning to the States and starting his studies at Yeshiva University, he continued to express his desire to enlist.

Over the next several months, Yaakov’s father had many conversations with him to explore his son’s reasons for wanting to join the army, to make sure he was aware of what it would really mean to be in the IDF. Satisfied with his son’s responses, his father told him, “You can go, you just have to make sure your mom agrees.”

But Chava wanted Yaakov to finish college first, and she struggled to accept her son’s dream.

“My husband said to me, ‘Yaakov’s a grown-up. Even if you don’t think he’s grown up, he has. What he’s doing isn’t wrong — it’s right for him, and this is what he needs to do,’” says Chava, explaining how she began to accept the situation. “I realized I can’t tell him what to do. It’s his life.”

When Yaakov came to her around Pesach and said, “Mommy, I’m going to join the IDF. Do I have your brachah?” she gave him her blessing and her full support. He left the States in August of 2021, joined a Hesder yeshivah, where they prepared him for the army physically, mentally, and logistically, and he was drafted in March 2022.

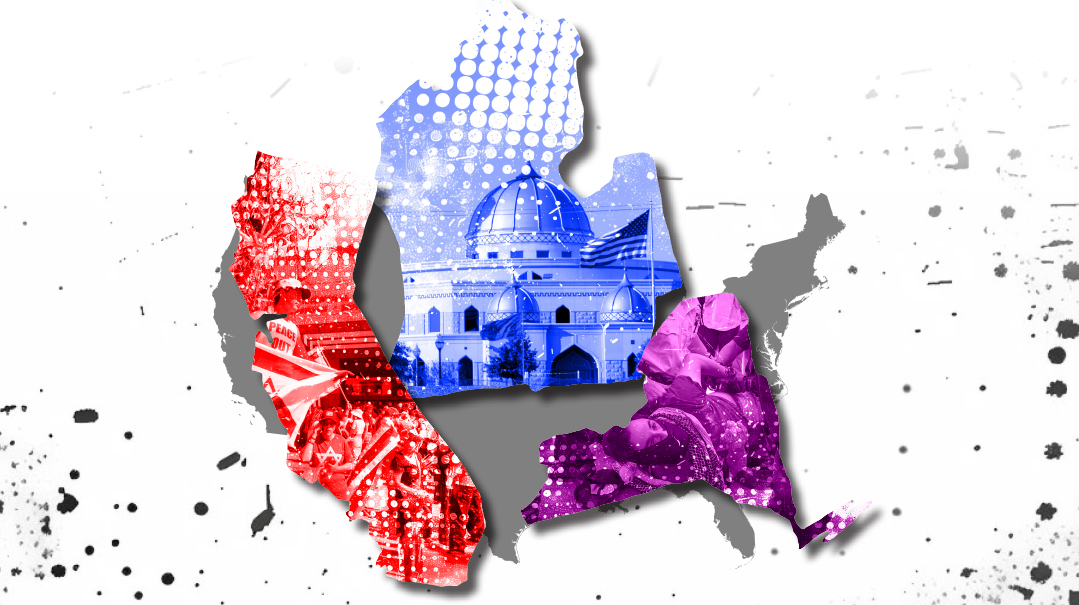

Melissa lives in Washington State, a little over an hour from Seattle, and just a couple blocks from a college campus where the large pro-Palestinian protests have been a source of much distress. Even though she lives in an area that has a small Jewish population, she has always been very active in Jewish life, serving on the board of her synagogue, Congregation Beth Israel, and Camp Kalsman, the URJ summer camp that her children attended.

“Going to a Jewish camp is what really instilled in all four of our kids a love of Israel and Judaism. Every summer, there’s a huge contingent of Israelis that come work at the camp, which is a big part of it,” shares Melissa.

Melissa’s son Isaac, one of a set of triplets, did a gap year in Israel with his sister. “They both came home saying that they wanted to make aliyah. I’m very proud of them and a little jealous,” says Melissa, who had wanted to go to Israel, but her planned trip had been during the First Intifada, which prevented her from going.

Isaac was part of a program to help new olim get settled and prepared for service. He spent four months on a base that Melissa describes as a Tower of Babel. “The only shared language is Hebrew,” she says. “There were new olim from South America, Russia, France, the US, and Canada.”

After months of language immersion, her son was drafted in May 2021, and ultimately ended up in a paratrooper unit. Melissa recalls how Isaac told her, “They don’t jump out of airplanes anymore, Mom, it’s modern warfare.” When I expressed surprise at that, she laughs wryly. “It’s not true. They do jump out of airplanes, for training. He knew I would be freaked out, so he didn’t tell me about that part until later.”

Rachel, from Charlotte, North Carolina, has four children in Israel right now. Three sons are serving in the IDF, and her daughter is in seminary. All of her sons attended Cooper Yeshiva High School for Boys in Memphis, Tennessee, and from there, went off to study in Israel. Her oldest son did two years of yeshivah, then joined the army. His brother stayed three years in yeshivah, then also joined the army.

By the time her third son went off to yeshivah in Israel, they could predict what was going to happen. “It wasn’t overwhelming for me because I only really had one child serving at a time,” says Rachel. But when the war broke out on October 7, all of her three sons were called up. “I never thought I would have three serving at the same time,” she says.

Reality Sinks In

“We were very slow to get news about October 7 because of Yom Tov,” says Rachel, looking back at the difficult time. “It was just trickling in. Monday was my lowest day because by Sunday night I really understood that all three boys had been called up. That really did floor me. I had to take off work and I couldn’t move. I didn’t remember to eat or brush my teeth. But from then on, I picked myself up, and I’m not like that now. I look back at that and I think to myself, ‘Girl, that was weak.’”

I ask Rachel, who works as a preschool teacher in a Jewish school and still has a young child at home, how she’s coping with the emotional maelstrom of having three sons in active service.

“I have a rule that I can cry once a day. So if I feel tears coming on and I’ve already cried, I tell myself that I’ve already had my one little mini breakdown for the day,” she responds. She also gained strength and perspective from a Meaningful People podcast episode with Racheli Fraenkel, mother of Naftali, one of the three boys kidnapped and murdered by Hamas terrorists in 2014, who said in the interview, “I can have anxiety, I cannot become my anxiety.” That has become Rachel’s mantra.

“It’s important to be happy. We have to be b’simchah,” says Rachel, who was energetic and positive through our interview. She clarifies that she’s not encouraging people to walk around like robots with a smile plastered on their face. “I’m allowed to feel my feelings. But I will not feel despair, and I will not be overcome with worry. I’m going to be happy, and I’m going to be cheerful, and I’m going to be strong.”

This is the approach Rachel takes when on the phone with her sons. Her third son, Yotam, has thanked her for being strong, positive, and for not making him feel guilty about serving. “He told me that my strength gives him strength. So I can cry when I’m off the phone with him, but there’s no whimpering with my children on the phone,” she says.

In October, Melissa’s son Isaac was about to be released from active duty. He was guarding a tiny post in the West Bank and had been sending videos of camels and whatever random things passed by, so when he sent Melissa a video of a jeep with riffraff in the back, she thought it was more of the usual.

Of course, it was anything but. Isaac let his mother know they were taking his paratrooper unit to a specialized base. A few weeks later, when the ground invasion began, Isaac told his mother they were taking away his phone. “That’s how you know that they’re going into Gaza,” she says. It was another five or six long weeks before she heard from her son again.

While other units would rotate out every few weeks, Isaac’s unit was in for a longer stretch, without those breaks. “Here in the US, people don’t have any idea, but in Israel, it was a really big deal because his unit, the active paratroopers, was the only unit that wasn’t given breaks.”

Two or three times during that period Isaac was able to call home, when somebody with a secure line happened to be traveling through Gaza. “They’d take pity on the troops and let a few people call home,” Melissa says. “Of course it was three in the morning here, and it was from a phone number we didn’t recognize, but after that first time, we knew. If we get a call at three in the morning, answer it. Just take it. We lived for those phone calls.”

Isaac is always positive and reassuring her that their spirits are good. “They know what they’re fighting for,” she tells me emphatically.

For Chava, her son’s service led him straight into the war, fulfilling a premonition she had felt when Yaakov enlisted. “The whole time when he was in the Hesder yeshivah, I was crying, even though he was safe. I had a lot of fear,” says Chava. “I kind of felt like something might happen, like war could break out, even though there was no threat of war in 2021 or 2022. I just had a feeling that during his service, there was going to be a time where there would be a war.”

From August 2021, when he moved to Israel, until he was drafted in March 2022, Chava worked on her emunah. “When I say worked on my emunah, I would cry. I would cry and say, ‘Hashem, please protect Yaakov,’ ” she explains. In the summer of 2022, she got to a place emotionally where she was able to let go of her worries and accept that Hashem was taking care of her son.

“I still work on my emunah every single day and have a conversation with Hashem to keep Yaakov safe, to keep the chayalim safe, to keep his unit safe,” says Chava in her soft, strong voice, “I give it over to Hashem every day and thank Hashem at the end of the day for keeping him safe. I have my moments, but mostly I’m strong.”

Life, Interrupted

Having a son in and out of Gaza has shifted Chava’s priorities. “I used to always study with my daughter for her tests, and ever since October 7, I can’t help her study anymore. I can’t do her homework with her like I used to.” Even though her daughter’s teacher is very understanding of the situation, Chava admits that it feels a bit weird to not be so on top of things right now.

“Education is very important to me, but right now there are other things that are more important. Like my son’s life.”

Making Shabbos and even weekday dinners has also become more challenging. “I can’t cook the way I used to. Sometimes making dinners has been overwhelming, so I just do the basics. I can’t make my normal, typical menus for Shabbos, so I focus on just getting it done.” If that means only making chicken, rice, and green beans, that’s what she does. “I used to feel bad that I wasn’t doing more, but I’m doing what I can,” says Chava.

There is a certain loneliness to the experience of having an emotional world that doesn’t mirror the reality of those around you. “Nobody can really know what I’m going through,” shares Chava. “Only those moms in the lone soldier groups that I’m in understand.” And even then, she feels a difference between mothers who have sons in Gaza and those who don’t.

For the younger soldiers, the onset of the war brought a pause to all life plans. Rachel’s second son had just completed his service and was about to start university on October 10. Melissa’s son was in the middle of the process of being released from duty. “He was supposed to be flying home to visit in November, then he was going to go back to Israel, work for a couple of months, and then travel,” says Melissa.

But for older soldiers who were already in the reserves for a while, their lives, already in full swing, were significantly interrupted. Craig’s son, Jonathan, finished his IDF service nearly a decade ago, and stayed in Israel. “He has golden hands, like my father a”h,” says Craig. “Jonny always had an affinity for building. He learned carpentry, tiling, roofing, plumbing, even basic electric wiring.” Jonathan met and married his wife and, over several years, built his own company, eventually employing about 50 workers to complete various simultaneous projects.

On the morning of October 7, Jonathan’s wife remarked to him that she thought she was hearing something unusual, like a barrage of fireworks. Jonathan recognized immediately that what she heard was not fireworks, and as the morning continued, he knew something wasn’t right. Within two hours of finding out what was going on, he was in Kfar Azza, fighting terrorists and helping Zaka with the aftermath. “As a lone soldier, he has an exemption not to do any further service. But he’s never exercised that right,” says Craig. Jonathan has only been home for a couple weekends since October 7; for the most part, he’s been in Gaza.

For Jonathan, going to fight means more than delaying some plans; it’s putting his whole business — and life — on hold. It also meant missing his wife’s graduation from nursing school. She celebrated alone. To add to the stress, Jonathan’s storage facility was broken into, and all of his work equipment was stolen. “Now when he gets out, he’s going to have to start from scratch,” Craig tells me with heartbreak in his voice.

This isn’t the first time Jonathan has been in combat. He served in Operation Protective Edge back in 2014, and Craig remembers distinctly how difficult it had been to send him off. Jonathan was visiting his parents when that conflict started, so Craig and his wife, Michelle, drove their son to the airport, acutely aware that they were sending him to war. “That was one of the worst days of my life,” Craig remembers. “I was wondering if I was ever going to see him again.”

Reflecting on the difference between now and then, Craig recalls how back at JFK in 2014, he couldn’t contain himself as his son boarded the plane back to Israel. Recently, when he traveled to Israel and saw Jonathan off at the border, he had a different reaction, even though the situation today is probably more dangerous. “Even though he was going into a war zone, he’s not a kid anymore. He’s a grown man, an experienced soldier who knows he’s acting as a shaliach of Hashem,” says Craig. “These soldiers are not regular people, they’re genuine yerei Shamayim. How many people would place their lives on hold to literally fight for Klal Yisrael?” he continues with awe.

Sarah’s son Ari was also long finished with his service as a lone soldier and was living in Herzliya, working in a PR Firm, and doing regular annual monthlong miluim service with his buddies. “He got called up right away,” says Sarah, who lives in Cleveland, just a few doors down from me. “I don’t actually know what he did there, but I know that he wasn’t on a base. He was down in Gaza. He was shooting his gun and sleeping in holes.”

Ari managed to get a message to his mother through a family friend, saying that he was okay and would call when he could. She heard from Ari a few days later. “What are you doing to protect yourself?” Sara asked her son. He shared that he had Tehillim, a siddur, two pairs of tzitzis, his tefillin, his yarmulke, and a quarter for tzedekah in one of his boots. “You don’t use quarters in Israel,” Sarah pointed out. “I know,” Ari responded. “But this way I’ll have to come to America to deposit the tzedakah, so nothing will happen to me.” Sarah told him to put a shekel in his other boot.

Despite her son’s confidence, it’s still, obviously, very stressful. “When your kid is in Gaza and you get a phone call at three in the morning, it doesn’t matter who it is. You answer that phone call because you don’t know if it’s your kid or somebody calling you about your kid,” says Sarah.

Even being in touch can be stressful, as Sarah discovered when her son made a group video call to the family. “We got to see his face. And he was filthy. I’ve never seen him so filthy, like encrusted with dirt,” she remembers. Her maternal instincts were triggered, and she found herself telling him to wash his face and then asking if he was brushing his teeth. “All the rest of the family on the call were asking pertinent questions and being so supportive and seemed to know all the things to say, and all I’m asking is, ‘Did you brush your teeth?’” she recalls incredulously.

“I’ve discovered that I’m okay for about four days,” says Sarah. “On the fourth day, I start losing my mind if he doesn’t call me or I don’t hear something about him. So I hold myself together until then, because you have to hold yourself together, and I busy myself by trying to collect money for him and his unit.”

Support and Understanding

It’s hard to be far from your children, all the more so when they are in a war zone. Recently, through Project Hug, a collaboration between the Friends of the IDF and Nefesh B’Nefesh, many parents of lone soldiers were able to travel to Israel to visit their kids. Rachel was able to see all four of her children. “It was amazing in the truest sense of the word. I didn’t think it would happen because there were so many logistics that had to work out. I took a leap of faith and left work early to go, and I was rewarded for that leap and got to see everybody.”

Melissa and her husband, John, also were able to see Isaac in person. When she heard about the trip, Melissa had initially dismissed the possibility because the program only provided a ticket for one parent, and she couldn’t imagine only one of them going, leading her to joke with her husband, “You want to arm wrestle for it?”

Also, who knew if their son would even be out of Gaza to see them if they did go? “But there was a lot of promotion,” she says. “Plus, I had about ten friends emailing me that I should go, so we applied for it, got accepted, and purchased a second ticket. There was no way one of us wasn’t going.”

Once they decided to go, they had to sign a form stating that they knew they may not end up seeing their son. “We had to sign three times on the form saying that we understood there was no guarantee we would see him, and then we had to sign again saying we understood. Like, we really, really get it, there’s no guarantee!”

What was it like flying all the way from Washington to Israel, knowing that in the end, they might not see Isaac? “We have a daughter in Israel we hadn’t seen in a year, so at least we would be able to see her. And Isaac hadn’t left Gaza since the first day of the ground invasion, so there was chatter that they might get a day or two of what’s called ‘refreshment.’” Also, Melissa had fundraised and purchased a number of safety glasses for their son’s unit, which they were bringing along with them, so the trip would still be well worth it, even if they did face the possible disappointment of not seeing their son.

In the end, it worked out beautifully. “We got there on a Tuesday, and Isaac’s unit was released on Thursday to a base, and then they bused them home Thursday night,” Melissa says. They were able to spend Friday and Shabbos together, enjoying Shabbos lunch with Isaac’s lone soldier host family, and then Sunday morning, he was back off to Gaza.

Fundraising and sending or bringing supplies is something many parents find helpful. Another way Melissa copes with the stress is to try to ignore the craziness in the world, though it has proved challenging. Her city council passed a ceasefire resolution that didn’t even mention Hamas, which was infuriating. “Blocking social media is really, really healthy,” she shares. Her community provides support, both with her synagogue and the surrounding Jewish community. While many families have a connection of one or two degrees to the war, Melissa’s family is the only one in the area with a child serving in the IDF.

“These are just normal kids who are fighting to protect their people,” says Melissa. “They’re not some meme. The public might think of the army as a non-human entity that just does things, but these are our kids, and they’re everyone’s kids. They don’t want to be anywhere near Gaza. They want nothing to do with it.”

Craig echoes that sentiment, noting with dismay that the intensity of the tefillos and Mi Shebeirachs in shul seems to have diminished since October 7. “What I really wish people would see is that these aren’t just nameless soldiers, these are our children. They’ve put their lives on hold to defend Israel and for all Jews everywhere,” he says.

While I had initially thought that Rachel might feel isolated in Charlotte, the community is small in number but strong in support. The shul gives Rachel’s husband the kibbud of reciting the Mi Shebeirach for the soldiers. Rachel has a friend who has pledged to bring her Shabbos flowers until her sons come home. At the beginning, they got a lot of meals. Though she was deeply appreciative of the support, she says, “I didn’t want to feel like we were in mourning. We weren’t, so I wanted that to stop.”

In addition to her local community, she has the support of the Memphis community where her boys went to school, as well as the Milwaukee community where her daughter attended high school. “They’re all davening for my boys,” she says gratefully.

Rachel receives support from outside the frum community as well. “People tell me they’re lighting candles for the first time in honor of my kids. I’ve asked people to take on a mitzvah, to pick a Jewish charity of their choice and give tzedakah in my sons’ honor. When I get a notice that someone’s made a donation, that they’re giving tzedakah in my kids’ merit, or they send me pictures of the candles, I love it. It makes me feel good. That’s what people can do,” she says.

Even with this support, it’s hard. Her third son has been in Gaza, and before he goes in, he drops his cell phone in a box that gets locked up. “Every minute I wait until he calls to tell me that he’s okay,” says Rachel. Once, he called from the hospital. He had gotten stung by bees and had an anaphylactic reaction. “I was happy that he was calling because I hadn’t heard from him, but he was calling from the hospital so I was concerned. I was happy, then sad, then happy. It’s a real roller coaster,” she says. Her son was fine, just annoyed that he had to bring an EpiPen with him when he went back into Gaza.

Her other sons have been up north since the beginning and do have their phones, but aren’t often able to call. “They’re busy. We talk to them, but not a lot. In the beginning, the ones up north couldn’t even charge their phones.” In the beginning it was very rough, remembers Rachel. Her sons’ units were in a forest, sleeping on the ground. A snake crawled into one of her son’s friends’ sleeping bags (he was fine). She wanted to send one of her sons something and asked where to send it. “My address is a waterfall,” was his response.

“I don’t think of myself as a strong person,” says Rachel. “This has shown me exactly how strong I am. How much I can handle. I don’t want to be tested any more than this — this has been hard. But I also never ever imagined this amount of pride. And I don’t think we’re supposed to be prideful, but I’m extremely proud of my sons. They are doing unbelievable work. They don’t complain. I know they’re cold. I don’t ask if they’re cold. I don’t ask if they’re hot. I don’t ask if they’re dirty. I don’t ask if they’re muddy. I don’t ask if they’re hungry, if they’re scared. They are. I never ask that. Because they are. But they don’t complain about it.”

In addition to her family and her four sisters, who provide support like only sisters can, Chava has found support through WhatsApp groups, including one of local mothers of lone soldiers. As some of those groups became less active, Chava found comfort in friendships with women who really get it. One is the mother of her son’s roommate from the Hesder yeshivah. “She’s been with me since the very beginning and has really truly been a good friend and support.”

Another source of support is a woman in her community who translates Hebrew messages from the Israeli Parents of Soldiers WhatsApp group that Chava is part of. “Yes, I could use Google translate, but it doesn’t always do a really good job and is confusing, so this wonderful woman lets me know what’s happening, when my son is coming out of Gaza, which is so good to know.”

She also appreciates how people from her community have shown their support. “There have been people who have come by who I don’t know who have brought flowers, or people who I do know but I wasn’t close to who have brought cards or cookies. A couple of people brought meals,” says Chava. Communal support also includes financial support and help in getting supplies to her son. When her son’s unit needed better boots, the community stepped up and got boots for the whole unit. Even though Chava appreciates all the support she’s gotten from the community, she says she doesn’t always feel like talking about what’s going on with Yaakov.

Parents who live in Israel have been very supportive. “They have been there for my son as much as they could,” says Chava. When her son came out of Gaza, all the Israeli parents who went to visit their sons in a park also brought Yaakov soda, chocolate, fruit and vegetables. “They’ve just been really nice, texting and WhatsApping to ask what they can do for my son.”

Through all the challenges, Chava finds comfort in her emunah and in her pride in her son. “Yaakov chose this journey. He chose to be in combat and join the IDF, and my husband and I chose to support him. Like I said, it wasn’t easy for me in the beginning to let him go, but once he did enlist, I supported him. And throughout this process, I feel that every soldier is a hero and every soldier is on a really high spiritual level because they’re putting their life on the line every single day that they are protecting Am Yisrael.”

“Because Yaakov is on this journey, he’s taken my whole family with him, and he has made my husband and myself increase our emunah, and therefore he has made us better. I’m not saying I’m on a high level at all,” insists Chava. “I’m just saying I’m not at the same level I was before October 7.”

Dos and Don’ts

It’s a fine balance when it comes to supporting families of lone soldiers. There’s a lot of range between melodramatic sentiments like, “I’m praying for you constantly, I’m thinking of you every second of every day,” which could feel too heavy, and the too lighthearted, “Oh, how are the boys?” as if they’re at camp. Even though it can be tricky to find the balance, it’s important to still try to provide support. Here are some suggestions:

- If you’re visiting Israel, ask a parent of a lone soldier in your community if you can bring something for their son.

- Ask what you can do to help.

- Let them know you’re thinking about them and their family.

- Daven for their children and let them know.

- Make a donation.

- Take on one small thing in honor of the safety of the soldiers.

- Be aware of your intentions. Don’t ask just to satisfy your curiosity.

- Be sensitive about complaining about your problems; keep in mind that your friend who has a child in active duty may not be as empathetic as usual.

Community of Chizuk

Derek and Devorah Saker, father and stepmother to a soldier on active duty, recognized the need to build a community where parents of soldiers could get chizuk. Derek, cofounder and CEO of JWed.com is used to thinking big, and, together with his wife, he started a WhatsApp support group for parents who have IDF soldiers on the front lines.

“These are parents of IDF soldiers who live in Israel as well as parents of IDF soldiers who live outside Israel, in the US, UK, South Africa, Australia, etc.,” says Derek. “These hundreds of parents in the group are extremely proud, but also, extremely worried — and many cannot sleep. Yes, we’re fighting a physical and spiritual battle, but no parent who doesn’t have a son on the front lines can really relate to a parent who does.”

Derek reached out to a number of well-known individuals from many corners of the Jewish world, including Rabbi Avi Shafran, Agudath Israel’s Director of Public Affairs; Rabbi Doron Peretz, Executive Chairman of Mizrachi Worldwide; Yaakov Shwekey, Matisyahu, Rebbetzin Tziporah Heller-Gottlieb, and Rebbetzin Lori Palatnik (who herself had a “lone soldier” son some years ago).

A growing number of individuals have graciously sent personal video messages of divrei chizuk/support directed to these parents. Eventually, Derek and Devorah created a website, parentsbeyachad.org, where anyone outside the WhatsApp group could see these videos. “I felt it very important for Klal Yisrael to see the outpouring of support to our soldiers from across the Jewish world,” says Derek.

The support group of parents is a very diverse group, including yeshivish, Chabad, Chardal, dati-leumi as well as non-Orthodox observances, reflecting the diversity in the IDF as well. “They are a microcosm of the Jewish world. Ashkenazi, Sephardi, religious, less affiliated. From wealthy homes, from poor homes. Israeli-born and born in chutz l’Aretz. Despite these differences, they are one. These soldiers do not wish to return to an Israel of October 6 with its divisiveness,” says Derek.

“As parents to soldiers on the front lines, we are ‘blessed’ to hear of some of the profound experiences of our children,” he says. “We as parents of course provide as much love as we can — but really for our soldiers, the ‘blood-brother’ love the members of a unit develop between one another is something singular. They live with each other 24/7. They protect each other 24/7. They would die for each other. And just by our own son’s example (and almost all other units) — they seek a new dawn, new leaders, not least for the sacrifices they’re making.”

(Originally featured in Family First, Issue 883)

Oops! We could not locate your form.