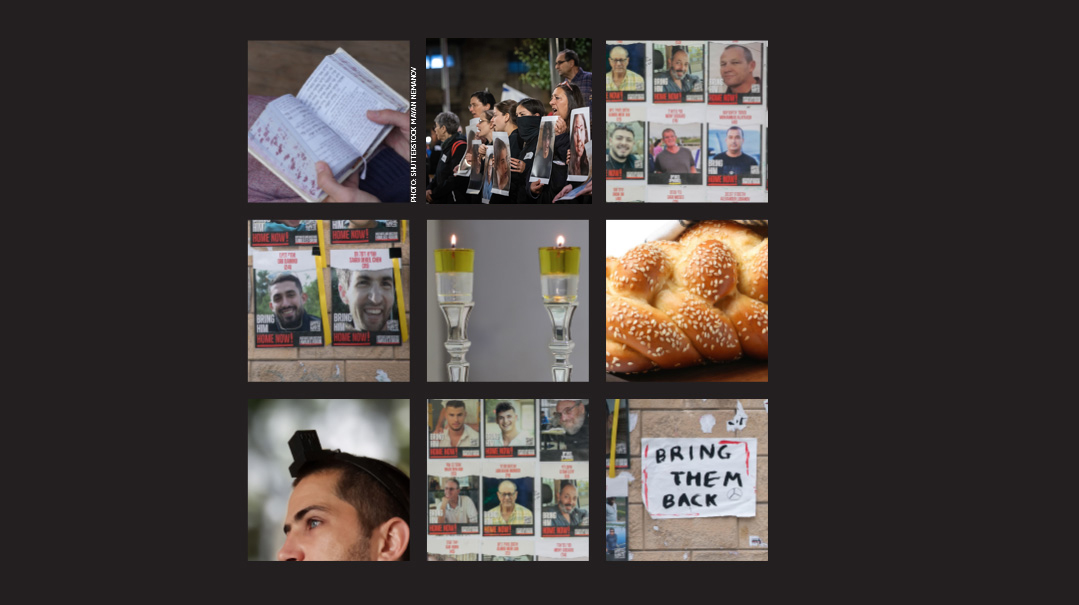

My Siren Call

I’m glad I could be with my brothers and sisters on day 100 as I was with them on day one

Photo: Flash90

I’ve arrived from America for two weeks to visit my children in Eretz Yisrael and see what I can do in my small way to help the war effort. I know that davening, saying Tehillim, and working on shemiras Shabbos is the best I can do, but perhaps I don’t know it well enough because I still feel I want to do something more tangible.

To be completely honest, my decision to visit Eretz Yisrael is driven also by a desire to address my increasing feelings of detachment from the war. In the beginning, my community and the worldwide chutz l’Aretz community were having weekly, if not daily, y’mei tefillah. We’d each chosen a 15-minute period in the day to recite our heartfelt Tehillim. While I still say mine every single day, and I still receive periodic calls for more Tehillim to be recited, I don’t feel the same urgency.

In the beginning, we checked for updates on the home front and around the world on the hour. There were worldwide Zoom meditations. Everyone was stressed, and we needed to connect because our brothers, sisters, children, and parents in Eretz Yisrael were under attack. This obsessive news checking has mostly petered out, but our family is still under attack! Hamas is as determined as ever to slaughter each and every one of us.

Walking in the streets of Yerushalayim, I see everybody going around, business as usual. There’s this sense that not much is going on, which makes it easy to lose sight of the fact that so much is going on. Our soldiers are still dying, and most of the hostages have not yet returned home.

One night, I travel from my daughter’s home to tie tzitzis in Har Nof. There are only five women there when I arrive; I’m told that at the start of the war, one hundred women gathered here. I’m surprised to see that the beged (garment) is green instead of the traditional white, but then it hits me: Green makes sense, to blend in with the camouflage of the army uniform. I’ve never tied tzitzis before, and though a kind, patient woman is teaching me, I end up having to redo three out of the four corners because I don’t realize that you consistently need to be working with two groups of four strings as you wind them around each other. When I finally finish, close to two hours later, I’m surprised by my feeling of great accomplishment.

The second time I come with my friend for the tzitzis tying, we are the only women there. (There’s one man in the other room.) I get the sense that here, as well, enthusiasm for the cause is flagging. It disturbs me. Just because we’re three months since the start of the war doesn’t mean that fewer of our people are being maimed and killed. Am Yisrael still needs our help.

The next day, I volunteer at a local Chabad center to cut, slice, assemble, and package tuna/cheese/chocolate spread sandwiches. This center has been making sandwiches daily for years for the many poverty-stricken families who can’t afford to send lunch with their children to school. Now they’ve added soldiers to their sandwich list, and I gather with a large group of Anglo-Israelis, Israeli-Israelis, religious and secular Jews. This is what I want to see.

But I’m greatly saddened when I glance at the wall and see the names and faces of all the young soldiers who died in combat. We make these sandwiches l’illui each beautiful neshamah. Thinking about every soldier, each victim of terror as someone’s child, perhaps someone’s spouse and parent breaks my heart. Miracles are occurring in this war; I hear stories all the time, but still, there are losses. Even one is too much. The only number of fatalities I want to hear is zero. “Today there were zero fatalities.” I can live with that.

On my next attempt to do my part, I help unpack clothing sent from America for the displaced families who’ve left their belongings in their demolished or war-torn homes. While I’m there, someone shows me a video clip of an interview between an Israeli broadcaster and a young religious woman with six children. The youngest, a ten-month-old baby, is in her arms as she talks about her tzaddik husband, a tzaddik who volunteered to fight and was subsequently killed.

“My husband made a cheshbon nefesh every single day,” the widow shares in the video. “I found his notebook. It says, ‘Today I got angry at my child. I will do better tomorrow. I spoke lashon hara today. I’m committing to learn two laws a day so that won’t happen again.’” In the background, we can see the recently deceased father throw a giggling toddler into the air, dancing and singing with his children. The widow speaks with love and pride, her voice breaking only slightly.

Where does this strength come from? I am so foreign to it. Doesn’t this young woman understand this is forever? She will never see her husband again in this lifetime; her children will grow up orphans. How can she have so much faith and love? I can’t understand it at all. I don’t even know why I’m watching this. I don’t want to hear any more.

Still, I witness more of this steadfast faith. I leave the apartment and wait for the bus back to town. This is not a particularly frum neighborhood, yet on a giant billboard, the length of a tall building, a neon-blue sign reads, Shema Yisrael Hashem Elokeinu Hashem Echad. A few steps away, there are posters plastered all along a busy street. Yisrael b’tach ba’Hashem, they declare. And when I leave the country a week later, another neon-blue banner proclaiming Am Yisrael Chai greets my eyes at the airport departures.

It’s normal, I know, that as days and weeks and months (lo aleinu) pass, I can’t keep up with the adrenaline of the initial moment. But coming here, I’m glad I could be with my brothers and sisters on day 100 as I was with them on day one.

(Originally featured in Family First, Issue 879)

Oops! We could not locate your form.