Mother of all Yeshivos: Uncovering the forgotten legacy of Mrs. Jennie Miller Faggen

Uncovering the forgotten legacy of Mrs. Jennie Miller Faggen, the most prolific Torah philanthropist of the interwar era

With additional Research by Gavriel Schuster and Chaya Sarah Herman

Photos: Rabbi Dovid Kamenetsky, Philadelphia Yeshiva Archives, YIVO, Temple University Archives, Kedem Auctions, DMS Yeshiva Archives, Jewish Exponent, Philadelphia Enquirer, Mir Yeshiva Archives, NYC Municipal Archives, LIbrary of Congress, Sotheby’s, Gratz College, Kevarim.com, Yoeli Hirsch, Shmuel Bitansky

Special thanks to Rav Shmuel Kamenetsky and family for their guidance, assistance, and encouragement

This article has been excerpted from Dovi Safier’s upcoming book on Jennie Miller Faggen (2024)

One serene summer morning, a stranger entered the prestigious Ponevezh Yeshiva in Bnei Brak. He walked through the building determinedly until he found a wall of dedication plaques. Then he stopped, and began to scrutinize each one. The students looked at him curiously before returning to their learning.

Finally the man turned around. “Where can I find Rabbi Kahaneman?” he asked in an American-accented Hebrew.

A nearby student, sensing the urgency in the stranger’s voice, escorted him to the office of Rav Avraham Kahaneman. As his son, Rav Eliezer Kahaneman, would later recount, this was no ordinary encounter. The man had come from Philadelphia with a question that would lead them both on a remarkable journey through time.

“Where is the plaque commemorating Jennie Miller’s 1929 dedication?” he asked. Rav Avraham, puzzled, pressed the stranger for details. With a trembling hand, the man removed a frayed, yellowed contract from a worn manila envelope. The document bore the signatures of Pesha bas Reb Yisroel Miller (Jennie Miller), the Ponevezher Rav — Rav Yosef Shlomo Kahaneman, and Rav Ephraim Eliezer HaKohein Yolles — the Philadelphia rabbi who helped draft the contract.

The truth dawned on Rav Avraham. Decades prior, before the horrors of World War II, Rav Avraham’s father, the Ponevezher Rav, had traveled from Lithuania to fundraise in America. There he met Jennie Miller Faggen, a Philadelphia woman of uncommon means and generosity. Profoundly moved by his impassioned speech at a local synagogue, Jennie had pledged $8,000 (which is approximately equivalent to $700,000 in 2023 when measured using gold as an inflationary measure.) to construct a new building for the Ponevezh Yeshiva, to be named “The Jennie Miller Building” in her honor. The contract specified that Jennie would retain naming rights were the yeshivah ever to relocate to Israel.

Trapped in Mandatory Palestine as war erupted, the Ponevezher Rav never returned to Lithuania. The yeshivah was obliterated, and its students and faculty were ruthlessly exterminated by the Nazis. Undeterred, the Ponevezher Rav resolved to resurrect the yeshivah in Bnei Brak, where it would ultimately become an iconic institution, surpassing its predecessor in stature and influence.

Confronted with the stranger and the long-forgotten contract, Rav Avraham Kahaneman faced an ethical quandary. Although the contract mandated Jennie’s naming rights, the yeshivah had not relocated to Israel; it had in fact been utterly destroyed and reborn under the same name elsewhere.

After much contemplation, Rav Kahaneman chose to honor the spirit of the contract and the memory of Jennie Miller Faggen. He commissioned a plaque commemorating her benevolence, acknowledging that her acts of charity deserved eternal recognition and celebration.

That plaque still hangs in Ponevezh today. It’s a rare reminder of a great woman who dedicated her fortune to buttressing the yeshivah world when Torah learning was hardly valued in America. Other than that plaque, scarce public reminders exist to commemorate her extraordinary generosity. It would take months of tenacious research, serendipitous leads, and several privileged conversations with the venerated rosh yeshivah of Philadelphia to unveil the full story of Jennie Miller, a patroness of yeshivos and gedolim, who was largely forgotten to history.

A young Ponevezher Rav with his son and successor Rav Avraham and son Yankele Hy”d

Chapter I: The Box in the Basement

IT

all began with a box in my basement.

I contracted coronavirus during the dark days following Purim of 2020, when fear over the pandemic was at its peak. Under strict quarantine in the basement, I decided to peruse some boxes that had been collecting dust in storage.

While most frum collectors tend to focus on antique seforim and chassidic artifacts, I had been quietly amassing a different kind of collection, a treasure trove of documents that I had nicknamed my “Vilna Genizah.” Within its dusty confines lay a range of fascinating materials, including letters, marketing materials, and fundraising ledgers from early 20th century yeshivos. Through the contents of this collection, I hoped to gain a deeper understanding of the yeshivah world during a critical time in its history.

Now, as I perused the diverse files for something of interest, a small pamphlet slipped out onto the dust-covered floor. The booklet was embossed with bold English letters proclaiming, “THE WORLD FAMOUS YESHIVA COLLEGE OF TELSHE, LITHUANIA.” It was dated 1929 and seemed to have been prepared by the yeshivah in advance of a fundraising visit to the US by Rav Elya Meir Bloch, the son of the rosh yeshivah Rav Yosef Leib Bloch.

The document began by outlining the more than half-century history of the yeshivah and quickly reverted to the current financial state of the yeshivah, which like most yeshivos at the time, was rather dire:

WHILE SPIRITUALLY the Yeshivah is at its height, its financial status is in fact all too lamentable. The budget of the Yeshivah — which is only $7,000.00 monthly — has not been met for many, many months….

American Jewry must fulfill its duty to our Torah and people and must rescue the famous Yeshivah of Telshe from closing its doors to the hundreds of applicants who are stretching forth their hands and clamoring for admission….

…Come to the support of the great Telshe Yeshiva and receive the reward of Heaven’s blessings that come to those who support the Torah.

In the year 1927, when a delegation of the Yeshivah visited America, it succeeded with the cooperation of the venerable Rabbi B. L. Levinthal, of Philadelphia, to interest the benefactress of every good cause, Mrs. Jennie Miller, of said city, in the institution, in conjunction with the Yeshivah, and Mrs. Jennie Miller, in her generosity, has undertaken to cover the greater part of the budget of the said “KOLLEL RABBIS” and because of same, the “KOLLEL” hereafter shall be known as the “JENNIE MILLER KOLLEL.”

I was immediately intrigued. Could it be true that the renowned Telshe Yeshiva named its kollel after an American woman? This would seem highly improbable to anyone familiar with Lithuanian yeshivos. But here it was in black and white. I was determined to uncover the truth.

Forgotten Philanthropist

A Google search netted some positive results. YIVO’s digital archive contained several letters written to Jennie Miller from various gedolim and yeshivos. There was a thank-you letter from the Chofetz Chaim in Radin, a letter of acknowledgment from Rav Chaim Ozer Grodzenski wishing Mrs. Jennie Miller success in her endeavors, and most surprisingly, a missive from the Mir Rosh Yeshivah, Rav Eliezer Yehuda Finkel, written on the stationary of a Mir Kollel titled, “The Cohlel of Ten Rabbis on the name of Mrs. Pesha Miller, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.” So there were not one, but two kollelim named for this forgotten woman.

Next, I checked the comprehensive book Ketzur Chalamish: The Golden Age of the Lithuanian Yeshivas in Eastern Europe by the incomparable yeshivah historian Dr. Ben-Tsiyon Klibansky, where I found mention of regular donations that Jennie Miller sent to the Lomza Yeshiva under the leadership of Rabbi Yechiel Mordechai Gordon:

“In 1925, Rav Yechiel Mordechai Gordon secured a pledge from Pesha Miller for $200 a month toward the new branch of Lomza in Petach Tikvah. This would be sufficient to support ten students.”

More evidence of her generosity surfaced while I perused the online archives of the Jewish Telegraphic Agency, which reported in 1930 that Rav Menachem Mendel Kasher had obtained a commitment from Jennie Miller Faggen to support a kollel of ten scholars to assist him with the research for his groundbreaking Torah Shelaimah project.

This bold initiative was an encyclopedic work that combined the parshiyos of the Torah with all the relevant passages from Chazal across Shas and all midrashim, even obscure midrashim from original manuscripts. The 38 volumes published during Rav Kasher’s lifetime surely consumed the bulk of his time and likely could not have been produced without Mrs. Miller’s assistance.

Slowly but steadily, I began to sense the unusual dimensions of her philanthropy. I had already studied the lives of other great Torah philanthropists of the time, dynamic figures such as Irving Bunim, Harry Fischel, Samuel Kaufman, and Mrs. Necha Golding in the US; and the legendary Russian microbiologist Dr. Waldemar Haffkine and Mrs. Flora Sassoon in Europe. While these individuals were all well-known philanthropic icons, none seemed to have reached ennie Miller’s level of giving towards yeshivos. Why was so little known about her?

I

continued my research, and the basic contours of the story began to take shape: Jennie Miller was a remarkable woman who was born in America and had been widowed twice. For the bulk of her life, she resided in the Strawberry Mansion neighborhood of Philadelphia, and during the golden age of European yeshivos in the interwar period, she became likely the world’s most prolific supporter of Torah. For many years, dozens of yeshivos received donations from her each month, and her 18-room mansion at 1837 North 33rd Street hosted some of the greatest gedolim of the era.

These gedolim described her in glowing terms. In a 1934 letter from Kletzk, Rav Aharon Kotler referred to her as “Esteemed Mother of Torah.” At the end of that same year, a letter of gratitude from Rav Yosef Eliyahu Henkin paid tribute to her generous support of Torah scholars: “Chanukah greetings to you, a modern Chashmonaite, who is most zealously and wholeheartedly aiding in the preservation of Judaism in our generation!”

Why, then, was her name so unfamiliar? How had her legacy of generosity fallen so utterly into oblivion? Surely there was an annual pilgrimage to her gravesite, I reasoned. Perhaps there were plaques paying tribute to her at the Mir Yeshiva in Yerushalayim, Lomza Yeshiva in Petach Tikvah, or the Telshe Yeshiva in Cleveland. Why had not even one of my six Bais Yaakov-educated sisters ever performed a song or play dedicated to her? Someone must have written a book or even an extensive article about her. Perhaps it was out of print or published in a hard-to-read academic Yiddish?

To find out more about Jennie Miller — and to understand why she’d virtually disappeared from the public consciousness — I realized that I needed to find something more than a newspaper blurb or sefer dedication (of which there were many). I would need to find someone who knew Jennie Miller personally.

After discovering that she’d lived into her nineties and passed away in 1968, I began to hope that there would still be someone around who remembered the good deeds and magnanimity of the woman popularly known in Strawberry Mansion as “Aunt Jen.”

The eBay Clues

I began sounding out fellow students and teachers of history. My email to noted Jewish historian Professor Shnayer Leiman was a good start. He responded:

Yedidi David,

I am, of course, familiar with the name Jennie Miller-Faggen. I have many of the envelopes she received from the various East-European institutions she supported. See attachment for a sample. But I know little about her.

He went on to suggest several others to contact for possible leads, but none had any further knowledge. I continued by trying some of my usual contacts. An email to Professor Shaul Stampfer netted me no results. The always-helpful Yeshiva University archivist Shulamith Z. Berger and her trusted teacher, Rabbi Dr. Aharon Rakeffet Rothkoff, were equally flummoxed. (Later on, Shulamith Berger was able to track down several letters in the YU Archive).

Arthur Kiron, the curator of Judaica Collections at the University of Pennsylvania, politely apologized that he could not offer any further information — but did send me several further local contacts. Then I tried Rabbi Moshe Kolodny, the long-time archivist at the America Orthodox Jewish Archives in lower Manhattan, and my close friend and colleague at Mishpacha Magazine, Yehuda Geberer.

Dr. Gil Perl, then Headmaster of Kohelet High School in Philadelphia and the author of a prolific book on the Netziv of Volozhin, couldn’t help me. My dear friend Dr. Zev Eleff was surprisingly lacking information. Someone suggested that I try the noted historian Gershon Bacon, who was born and raised in the area. (I even went so far as to reach out to Professor Noam Chomsky, whose father was involved in Jewish education in Philadelphia during Jennie Miller’s lifetime.) Klum. Gornisht. Nada. Nothing.

Even as the these historians lacked further information, more clues began to appear in the form of primary sources. Letters and charitable receipts from venerable rabbinic figures and great yeshivos were regularly posted on the websites of various Jewish auction houses, book dealers, and even eBay.

Where were these letters coming from? There seemed to be dozens, possibly hundreds that had passed through these channels. Perhaps Jennie Miller had some descendant who was selling off the “family archive”?

I reached out to Chaya Sarah Herman, a preeminent Jewish genealogist who is a family friend and has helped me solve these sorts of mysteries in the past. I asked her to try and put together some sort of family tree. Perhaps once that was complete, a good old game of Jewish Geography would locate a relative who could fill in the elusive story.

Meanwhile, I endeavored to contact several rabbanim and rebbetzins whom I thought might know more. I emailed Rabbi Elazar Meir Teitz of Elizabeth, NJ, whose father Rabbi Pinchas Mordechai Teitz had been active in Telshe fundraising circles during the 1930’s and perhaps had visited Mrs. Miller. He apologized that he had nothing to share. I reached out to Rabbi Paysach Krohn, whose mother grew up in Philadelphia and had authored a charming memoir chronicling her childhood there. Surprisingly, he knew nothing about Jennie.

The great gaon Rav Moshe Brown of Far Rockaway, whose shul I grew up in, was one of Philadelphia’s brilliant native sons. Perhaps he would have heard something from his father, Dr. Joseph Brown? Or perhaps his Rebbetzin Leah (née Weinberg), who also hailed from an influential frum family in Philadelphia, would be familiar with Jennie? Neither of them had heard her name before. I asked my dear friend Rabbi Osher Rosenbaum to check with his great-aunt Rebbetzin Shoshana Gifter (wife of the Telsher Rosh Yeshivah, Rav Mordechai Gifter) — but she was unaware of the story.

After months of inquiries and research, I still hadn’t made the hoped-for progress. I had the bare outlines of a story, but not much else. I had established that a great philanthropic woman in Philadelphia donated tremendous sums of money to Torah causes in the early 20th century — but I hadn’t managed to track down the motive or real story behind her largesse, or even the source of her funds.

I could have given up and relegated the Jennie Miller file back to my basement. But just then, with the help of Chaya Sarah Herman, my very curious friend Gavriel Schuster, and literally dozens of visits to libraries, archives, and private collectors from across the world, I began to make progress. Finally, I began to cobble together bits and pieces of Jennie Miller’s life.

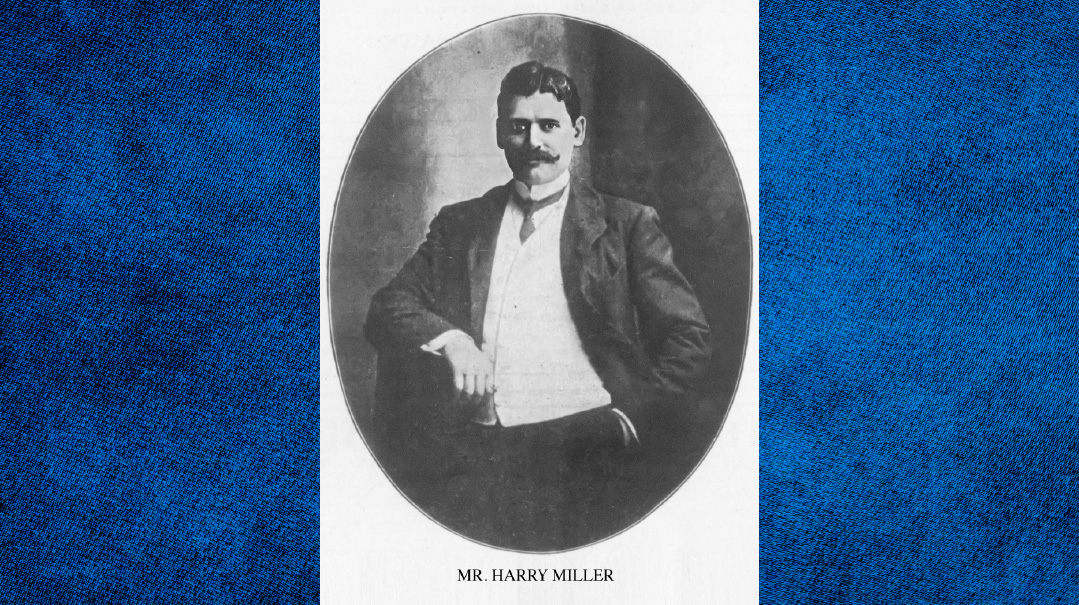

A rare photo of Jennie’s first husband Harry Miller

Chapter II: Abiding Faith in the Treifene Medineh

You might say that Jennie’s story dates back to the years directly leading up to the Great Immigration (1820-1880), an era of Jewish immigration to the United States from the areas in Central Europe that would later become ratified as unified Germany. A portion of those immigrants were single women of marriageable age who were sent by their parents to the New World in search of a match that would provide them with a more secure and prosperous future.

It was just shortly following the cease of the Franco-Prussian War and the proclamation of the Second German Empire by Kaiser Wilhelm I and Otto von Bismarck, that 19-year-old Hannah Cohen (then known as Hannchen Wolff) departed Hamburg, Germany, alone in steerage class on the S.S. Germania, never to return to her home in Gembitz (district of Posen). She arrived in New York City on June 28, 1871 and likely moved in with the Kutner family, who were relatives of her mother, Tzirel Wolff (nee Kutner), on the Lower East Side.

Just 15 months after she arrived in America, she married 23-year-old Israel (Yisrael) Cohen, a fellow native of the Posen region hailing from the town of Wittkovo, which was just a few miles from her hometown of Gembitz. Municipal records show that the wedding was officiated by a local rabbi named Rabbi Shlomo Beiman.

If prosperity and stability were what Hannah sought in America, she was soon disappointed. Israel Cohen eked out a meager living as an expressman, tasked with the delivery and security of a variety of commodities, such as gold and currencies.

The Lower East Side of the 1870’s was quite different from the Eastern-European hub that it morphed into decades later. It was then nicknamed Kleindeutschland (Little Germany), an homage to its predominantly German population. It was there that Pesha (Jennie) Cohen was born in 1874 (There is a lot of confusion over her year of birth, but both census reports and her marriage certificate indicate it was 1874), followed shortly thereafter by a brother named Shlomo Zalman (Samuel).

It wasn’t until 1894 that the Chofetz Chaim issued his famous plea to American Jewry in his sefer Nidchei Yisroel (1894) declaring, “If a ‘proper person’ has made the tragic mistake of emigrating America, he must return to his home where G-d will sustain him. He must not be misled by thoughts of remaining there until he becomes wealthy.” Only back in Eastern Europe, he believed, could a Jew live a proper religious lifestyle and “bring up his children in Torah and piety.”

According to acclaimed historian Jeffrey Gurrock, one of the earliest such statements came in 1862 from no less than Rav Yosef Shaul Nathanson of Lemberg, the acclaimed author of the responsa sefer Sho’el u-Meshiv, who had cautioned that “dedication to the Torah is weak” in that far-off land to where so many “patently unknowledgeable people are migrating.”

The Cohen family belonged to the small minority that withstood that powerful tide, remaining true to their roots and maintaining an observant life. Overall, Jewish immigrants from the Posen region, which was geographically (and religiously) closer to Poland, remained more devoted to traditional life, even in the “treifeneh medineh.” An anecdote from this period shared by the historian Hasia R. Diner, which occurred around that time in nearby Washington, bolsters that assertion:

To take but one example, thirty-eight members of the Washington Hebrew Congregation, many of them recent arrivals from Posen, withdrew from the city’s only synagogue when it installed an organ in 1869. They objected with equal vigor to the conversion of the service to an English-only ritual and to the elimination of the kiddush, the prayer ushering in the Sabbath, on the grounds that it blessed G-d for having chosen the Jews “among all the nations.” The dissenters believed that only Hebrew should be the language of worship and that texts like the kiddush could not — and should not — be altered. Those who seceded formed Adas Israel, the capital’s second congregation.

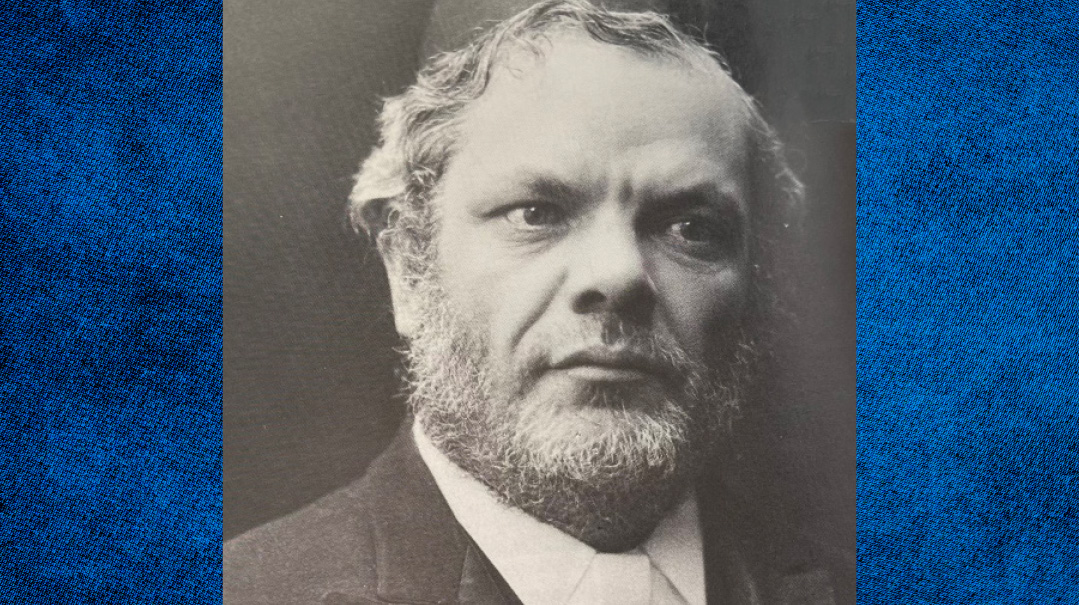

Rabbi Dov Aryeh (Bernard) Levinthal (1864-1952) stood at the helm of Philadelphia Jewry for more than 60 years

Faith Amid Misfortune

Jennie was one of those rare youngsters who held on to traditional values despite the odds. In a recently discovered interview with Jennie Miller (née Cohen) published in 1924 in the Yiddishe Velt, the writer gives us a rare glimpse into Jennie’s upbringing:

She is herself an American by birth. She was born and bred in the city of New York. And yet, for all the diverse temptations that must have assailed her, Mrs. Miller has zealously guarded in spirit and indeed the principles of Orthodoxy which formed the foundation of her own home life. The power that sustained her in her moments of despair was a hope derived from the religious training received as a young girl and fostered throughout her life.

On February 3, 1893, tragedy struck the Cohen home when Israel Cohen suffered a heart attack and perished. After extensive searching, we discovered his grave at one of New York’s oldest Jewish burial spots, in the Gniezno Landsmannschaft section of the Bayside Cemetery. He left behind a grieving widow and two orphans whose inheritance included little but their faith in the One Above. As the Yiddishe Velt put it:

….She (Jennie) had hope. A hope, a belief that had been instilled in her from her very childhood, that had grown with the years. An abiding faith in the ultimate good even within evil and misfortune. It was that which buoyed her up, forced her to walk erect, with head up and eyes forward, to take up the thread of life once more even though her nearest and dearest had been taken from her. And then, while everything still loomed empty before her, she conceived a splendid idea of creating happiness out of misfortune…. As she said, “I don’t know what would have become of me if I had not this belief and this hope to bolster me….”

As I was soon to learn, Jennie lived a life that was marred by one tragedy after another, but buoyed by her faith and commitment, she drew a positive picture and lived with joy and optimism.

Two years later, records show that Jennie Cohen married an entrepreneurial 27-year-old immigrant from the Yanishkel region of Lithuania named Harry Miller. Much of Harry’s background remains shrouded in mystery, but we do know that he was likewise orphaned at a young age. Shortly thereafter, the new couple settled in Philadelphia, which was then home to the third-largest Jewish population in America (after New York and Chicago).

Philadelphia had also recently become home to a very determined rabbinic transplant named Rabbi Dov Aryeh (Bernard) Levinthal; his arrival in 1891 is in fact viewed as a turning point in the city’s Jewish history.

Born in a suburb of Kovno in 1865 and descended from 11 generations of rabbis, Rabbi Levinthal received his training and ordination from Rav Yitzchak Elchonon Spector and Rav Shmuel Mohilever. At the age of 19, he married Mina Kleinberg.

Rabbi Levinthal’s son, famed jurist and community leader Louis Levinthal, recalled that even after his father accepted the offer of a rabbinic pulpit in Philadelphia, those around him pleaded with him not to go, saying, “The land is treif, the people are treif, even the stones in America are treif!”

Their fears were not unfounded. “I found virgin territory here,” reminisced Levinthal in a 1934 interview quoted in Alex Goldman’s Giants of Faith. “Plain and simple, and undone. Even the ground, as it were, was not prepared, not ready for sowing. I had to begin from scratch. The road was strewn with mountains to hurdle. I was not to be deterred.”

Rabbi Levinthal’s 60-year tenure at the helm of the Philadelphia rabbinate was in its infancy when the Millers moved to Philadelphia. Their first home was on North Sixth Street in the Society Hill neighborhood, which was then the hub of Jewish life for the city’s Russian immigrants. The city was dotted with landsmannschaft shuls that focused on social issues rather than worship and prayer, so much so that Rabbi Levinthal once described the primary function of these shuls as a place where one went to recite the gomel blessing after arriving in America.

Interestingly, it was not at Ahavas Chesed Anshe Shavel, the Ponevezher Lodge, Shomrei Emuno Anshei Kelm, or Tiferes Israel Anshe Lita that the Millers chose to daven, but at one of the more prominent local congregations, a Galician congregation called Bnei Halberstam.

Back in 1884, seven immigrants from Galicia established one of the first chassidishe shtiblach in America (and the first in Philadelphia), which they named Bnei Halberstam, evoking the name of Rav Chaim Halberstam, the Divrei Chaim of Sanz. Two years later they celebrated a gala hachnassas sefer Torah after receiving a specially ordered sefer Torah from a prestigious sofer back in Sanz, dedicating it in memory of the Divrei Chaim, who had passed away several years prior. This unique event was celebrated across the city, piquing the interest of even the most secular of Jews.

Records preserved by the Philadelphia Jewish Archives, (now housed at Temple University), along with local newspaper reports suggest that Harry likely met his future business partner, Abraham Pleet, at Bnei Halberstam.

Pleet had immigrated to America as a teenager from the Lithuanian city of Shadova. Upon his partnership with Harry Miller, who had risen from a simple peddler to proprietor of a respectable business where he bought and sold cloth materials, the firm of Miller & Pleet was established.

During the turn of the century, Philadelphia was home to a flourishing textile industry that employed over 40 percent of the city’s workforce, including a significant portion of its immigrant population. Jewish immigrants skilled in tailoring and dressmaking were drawn to this city of abundant work opportunities.

Archival issues of Textile World magazine from the early 1900s, housed at the New York Public Library, showed that Miller & Pleet quickly expanded their business and prospered in the worsted fabrics trade (used for high-end suits and coats). This success prompted them to explore the possibility of cutting out the textile middlemen by purchasing their own mill.

In 1905, they signed a lease with the Delaware County Trust Company for a 20-acre mill property in the small town of Lenni, situated along Chester Creek, near the Delaware state line. The agreement included water rights and 25 “dwelling houses” for employee accommodation. Three years later, they opted to purchase the mill and renamed it Yorkshire Worsted Mills, which, after renovations, became one of the largest and most active in the region.

Harry also ventured into the real estate business and held significant investments in public securities and government bonds. When he and other prominent Jewish businessmen experienced discrimination at the hands of the exclusively gentile loan committees at local banks, they boldly opened their own bank, named People’s Trust. By 1910, 42-year-old Harry Miller had become one of Philadelphia’s wealthiest Jews. But his similarities with other affluent Jews in the city ended there.

Harry and Jennie observed with concern as their fellow Jewish Philadelphians drifted away from traditional Judaism, embracing the emerging Conservative and Reform movements instead. Feeling the need to respond, they sought to collaborate with someone who shared their convictions. Rabbi Levinthal, who had swiftly risen to prominence as one of America’s foremost rabbinic figures during his first decade of service in Philadelphia, seemed the perfect ally.

At the time, cities across the country were courting Rabbi Levinthal with major offers. When Rabbi Levinthal began to seriously consider an offer to lead Chicago’s Russian congregations, Harry stepped in to ensure that their beloved leader would stay put. In order to do so, he gathered a group of the city’s most important leaders and began to organize a kehillah system, which would afford Rabbi Levinthal control over consequential and potentially contentious issues — from kashrus and gittin to a unified Talmud Torah system. After spending a few days pondering the offer, Rabbi Levinthal agreed to Harry Miller’s proposal and vowed to stay in Philadelphia — where he would serve as the city’s leading rabbinic figure (across all denominations) until his passing in 1952.

Memories of a White Limousine

Now that I had established the source of Jennie’s wealth and the fact that her husband had served as the first president of the Philadelphia Kehillah and forged a close relationship with Rabbi Levinthal, I felt I was getting a bit closer to the source. Rabbi Levinthal, after all, was connected to leading rabbanim and roshei yeshivah from across the world. My next move was to place an ad in Philadelphia’s Jewish Exponent, which after 135 years was somehow still around:

Surprisingly, the ad netted me results, only they weren’t exactly the type I’d been hoping for. My phone began to ring with calls from older residents of Philadelphia (all still under strict quarantine orders) hoping I’d be interested in talking to a former resident of the city — even if he/she happened to know nothing whatsoever about the subject at hand.

Almost none of these friendly, elderly Philadelphia Jews were familiar with Jennie. Most were lonely older women who just wanted to schmooze. About anything. “Who is this Jennie Miller and why are you so interested in her?” they asked, in a way that only a doting Jewish grandmother could.

One of my first respondents, Sylvia, was born in Philadelphia in 1927 and left as a three-year-old. Our first call got slightly awkward when the charming nonagenarian with the heaviest Philadelphia accent I’d ever heard asked if I was single — she had a local niece whom she was hoping could meet a nice Jewish man.

Then Albert K. called from a local senior home, and I had the sense I was getting closer. He had grown up in Jennie’s neighborhood and vividly described playing ball on a stoop of the Lichtenstein home, next door to Jennie’s mansion. He recalled her chauffeur washing the white limousine that transported Jennie and her guests around town.

Some more basic information came via other callers, but not much of substance. Perhaps the window had closed and it was just too late to find someone who could actually recall Jennie and add some substantive information to my search. But I wasn’t ready to abandon it just yet.

(L-R) Rabbi Bernard Levinthal, the Tolner Rebbe (behind), Jennie Miller and Louis Levinthal at a Talmud Torah groundbreaking in 1927

Chapter III: Finding Jennie

AS I was soon to discover, it wasn’t just “someone” who recalled Jennie Miller; it was no less than the zaken hador, one of the great gedolim of our times. And he didn’t just know of her; he and his family in fact shared a close relationship with her. But it took me some time, and more effort, to establish that link.

I reached out to Rabbi Yehuda Shemtov, whose father Rabbi Avraham Shemtov is the longtime shaliach of the Lubavitcher Rebbe in Philadelphia and is widely connected across the city. He recommended that I speak with long-time Philadelphia resident Dr. Joseph Mandelbaum, who serves as the president of Chevra Bnei Moshe, the chevra kaddisha of Philadelphia.

I spoke to Dr. Mandelbaum for more than an hour. He knew the story of Jennie Miller, and while was too young to have been acquainted with her personally, he filled in several important blanks. Dr. Mandelbaum told me that Harry Miller passed away after a short illness in 1923, leaving Jennie an extraordinarily wealthy widow. During Harry’s lifetime, the Millers invested incredible sums to improve the city’s local Jewish educational infrastructure, including the Central Talmud Torah network of Rabbi Levinthal.

It didn’t take long for me to find evidence of these activities in various newspapers of the time. In fact, there was hardly an institution in the city that did not benefit from the Millers’ largesse. In 1909, they donated four and a half acres of land to build the Hebrew Sheltering Home, which cared for homeless and neglected children. Shortly thereafter they endowed the adjacent infant shelter with an accompanying daycare center. Abandoned babies were cared for in the “Harry Miller Ward,” a dedication likely spurred by Harry and Jennie’s mutual experience as orphaned children.

As with all of the institutions they established, the Exponent noted that they wrote up a contract with the trustees of both the orphanage and school stipulating that their kitchens remain exclusively kosher for perpetuity, a rarity at the time.

Among all the Millers’ projects, though, there was one that struck me in particular.

Neither Gold nor Yiddishkeit

In 1903, the Ridbaz, Rav Yaakov Dovid Willowski, the Rav of Slutzk, was invited to Philadelphia by Rabbi Levinthal to address the second convention of the Agudath Harabonim, which Rabbi Levinthal had cofounded the previous year.

In his speech, the Ridbaz assailed American Jewry for abandoning the chinuch of their children, relying instead on a public school system where “too much time was spent in athletic sports and pastimes and useless amusements.” He explained that with the establishment of Jewish schools, children could still get a proper education while spending the time they were currently wasting on extracurriculars. learning Torah.

(On his previous visit to America in 1900, the Ridbaz was heartbroken by the low religious standards he witnessed and exclaimed that, “Whoever comes to America is a poshea Yisrael, for here, Yiddishkeit and the Torah shebe’al peh are trodden underfoot…. It was not only their homes that the Jews left behind in Europe; it was their Torah, their Talmud, their yeshivos and their talmidei chachamim.” He closed the speech with a knockout punch: “In Europe, they say that Yiddishkeit in America is nothing, but gold is found in the gutter. The fact is, neither gold nor Yiddishkeit is to be found here.”)

In the aftermath of the 1903 convention and the Ridbaz’s impassioned call for standardized Torah education, Rabbi Levinthal vowed to revamp the city’s lackluster Central Talmud Torah, which he had founded together with Dr. Cyrus Adler and Judge Mayer Sulzberger soon after his arrival in the city a decade prior. With the words of the Ridbaz, who had bemoaned the fact that “there were 13- and 14-year-olds who could not read from the siddur or even repeat daily blessings” surely echoing in his mind, he made his first major move.

In September he announced the opening of an afternoon yeshivah for high school students, where Gemara would be taught by proper rebbeim (for a time he taught the highest class). At first, enrollment was weak, but the following year, more than 60 students enrolled.

The Millers became the most significant donors to this new high school, which was named Mishkan Israel, presumably in memory of Jennie’s father Yisroel Cohen.

As the Millers’ philanthropy brought the community a plethora of new Jewish schools as well as other modern facilities dedicated to the young, their close friends could not ignore the elephant in the room. The beloved patrons of their community, who were now married for over a decade, had not yet merited children of their own.

It was clear, however, that Jennie was a remarkable woman with a unique perspective on life. Bnai Jeshurun’s Rabbi Shlomo Barzel, who lived next door to her, shared a story about Jennie’s response when faced with expressions of pity over her childlessness. Instead of feeling sorry for herself, she would point out the incredible opportunity she’d been given to support Torah, and with a wink, she’d cite the Gemara (Sanhedrin 19b) that says, “Whoever teaches someone’s son Torah, it is as if he sired him.”

The Miller Community Center was host to thousands of Jewish schoolchildren from several Talmud Torahs and eventually Beth Jacob, which was Philadelphia’s first Jewish Day School, founded by Rabbi Chaim Uri Lipschitz

MY conversation with Dr. Mandelbaum quickly morphed into a more personal one, as he told me about his own life in Philadelphia, where he was one of the first students at Beth Jacob, the first full-time Jewish day school in Philadelphia, located in the Strawberry Mansion where Harry and Jennie had moved in 1910. The school was housed in an annex of the Bnai Jeshurun Synagogue, which carried the Miller family name, having been dedicated by Jennie in memory of her husband in 1924.

That dedication was the very event for which Jennie sat down for the aforementioned interview with the Yiddishe Velt and delineated her worldview, which centered upon the importance of Jewish education.

She is an unassuming person, rather flustered by this business of being interviewed. The fuss one has made about her $50,000 donation, by the press, quite naturally is pleasing to her, and yet very plainly she is very much surprised.

The principles she enunciates, her statement that every Jewish child must have a real Jewish education in the history of his people and the tenets of his religion, springs from a simple and sincere faith.

Religion has proved her mainstay in her darkest hour…. That which gave her strength must be nurtured in every Jewish youth.

“They call us [women] the builders of the home,” she continued. “A vocation of which any woman might be proud. That which any woman could devote all her energies, all her talents, and consider it a task worthwhile. Molding human beings — could anything be more stupendous, more inspiring, more worth concentrating upon?

“Many have tried. And how many have failed! Why has it been so difficult to see that Jewish home, without which Judaism is robbed of its flavor and its meaning? To run a Jewish home in which the Jewish children are ignorant of things Jewish is meaningless. How can one expect a young child to grow up if it has not something on which to pin its faith — something intangible and unarticulated, perhaps, and yet something that will inspire his imagination and hold his loyalty. Religion! That is what the Jewish home lacks — religion and knowledge….

…“What a joy there is in giving!” she exclaimed after a pause. “If only they [the rest of the wealthy Jews in Philadelphia] would know how happy it makes one to help others, they would give generously. What greater joy than to help a child? Think of these innocent little children. They look to us for help, to show them where to go, and what path to take. And the joy of directing them right!

“Money?” she scoffed. “What good does money do if you can’t spend it for something that will give you pleasure?

“We can’t take our fortunes with us to the grave. Why should one wait until one is dead to plan good deeds? Far better to do them when one is alive and able to enjoy them. I have never been happier,” she said, “than I am now, since this thought of endowing a community center came to me, since I have thrown myself into the practical work that followed.”

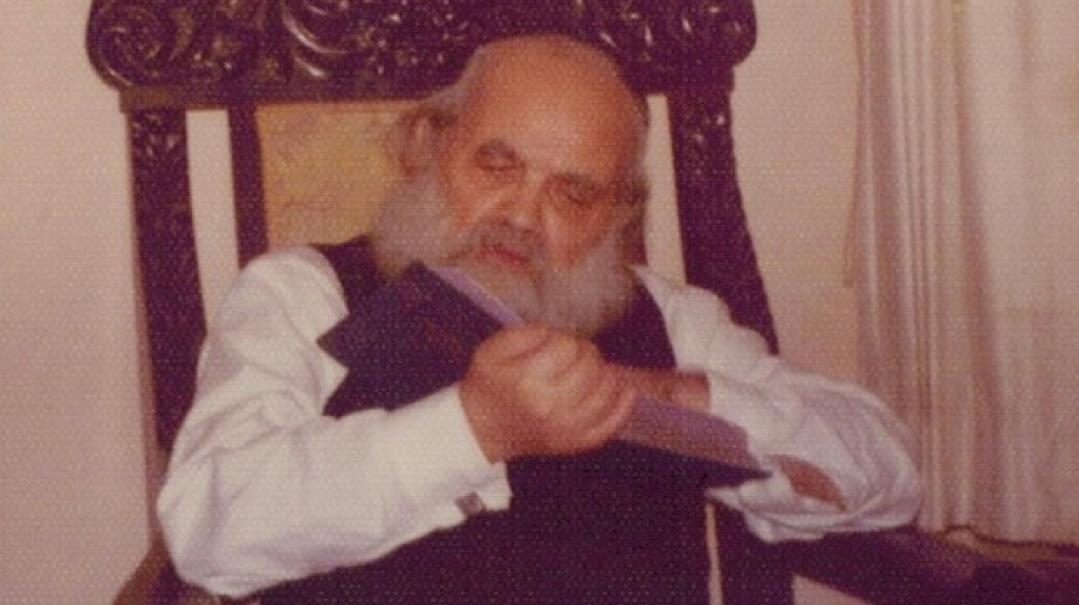

Rav Yaakov Kamenetsky sitting in the “Chair of the Gedolim” at the Kamenetsky home

Chapter IV: A Home and a Haven

AS I reached the end of my conversation with Mr. Mandelbaum, he mentioned something that would become a turning point in my exhaustive research: “Did you know that Jennie Miller was honored by the (Philadelphia) Yeshiva in 1956?”

Flabbergasted, I realized that I’d totally overlooked the Philadelphia Yeshiva angle. After I completed the call, I quickly emailed Rabbi Dovid Kamenetsky, a son of Rav Shmuel and a world-class Torah scholar, author, and researcher in his own right, asking if he had ever heard of Jennie Miller-Faggen. He immediately replied:

Indeed! She was a close friend of our family. We knew her well and when I was a kid we used to visit her in an old-age home in Atlantic City. We have many presents from her and a beautiful chair adorns my parents’ home on which all the gedolim who came to the US between the wars sat on when they visited her. She was one of a kind, a descendent of Rabbi Akiva Eiger who paid $150,000 to a Russian brother-in-law to come to the US and perform chalitzah during the 20s.

The chair, how had I forgotten the chair! It was all becoming quite clear to me now. This was the famous chair that has adorned Rav Shmuel’s living room for the past nearly 70 years. Rabbi Moshe Bamberger, Mashgiach Ruchani of Beis Medrash L’Talmud/ Lander College for Men, featured it in his book, Great Jewish Treasures (ArtScroll/Mesorah Publications), describing Jennie Miller as follows:

Among those who visited her stately home in the Strawberry Mansion neighborhood of Philadelphia were such Torah leaders as the Lubliner Rav, Rabbi Meir Shapiro; the Kovna Rav, Rabbi Avraham Dov Ber Kahana Shapiro; the Baranovitch Rosh Yeshivah, Rabbi Elchanan Wasserman; the Kamenitz Rosh Yeshivah, Rabbi Boruch Ber Leibowitz; the Grodno Rosh Yeshivah, Rabbi Shimon Shkop; and the Lubavitcher Rebbe, Rabbi Yosef Yitzchak Schneerson.

Upon their arrival, these august guests would be ushered into the dining room. At the head of the table stood a large regal chair, upon which their hostess insisted that they sit, as it was there exclusively for them. In this way, she demonstrated her genuine kavod HaTorah — a calling to which she dedicated her life. Mrs. Miller Faggen enjoyed a very close relationship with yblch”t the Philadelphia Rosh Yeshivah, Rabbi Shmuel Kamenetsky and his family. As she aged and could no longer maintain her large home, she relocated to an apartment on the New Jersey shore. On the Purim prior to her move, she sent the Kamenetsky family — along with her shalach manos — a cherished gift, the legendary chair of the gedolim.

Two days later, I got in the car with Gavriel Schuster and drove two hours to Philadelphia to see Rav Shmuel and his rebbetzin. Along the way, we decided to make a quick stop at 1837 North 33rd Street, the Strawberry Mansion home where Jennie Miller-Faggen had resided for more than 40 years.

Despite the downward trend the neighborhood had taken, it didn’t take too much imagination to see why 33rd Street was once home to Philadelphia’s wealthy and powerful during the interwar period. The Miller home was located on a wide promenade, directly facing picturesque Fairmount Park. Standing four stories high, it was among the only houses on the block that remained in good condition as the area had fallen into disrepair.

As luck had it, the current owners were standing outside, tending to their garden. I introduced myself and awkwardly attempted to explain the significance of the home that they resided in. Surprised but gracious, they invited us to come inside and tour their immaculately restored mansion. I’m not usually one for adventure, but this seemed like a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity.

Upon entering the home, it struck me that this was no simple abode. I began to tally a list of the rabbinic greats who had been inside this home nearly 100 years earlier. It was clear that I was standing on hallowed ground. I bounced up and down the steps in a trance, hardly listening to my host’s words as I transported myself back to another era and recalled just one of the historic events that had occurred there.

“Upon entering the home (of Jennie Miller), it struck me that this was no simple abode”

A Dear Lady with a Jewish Heart

In August of 1926, Rav Meir Shapiro traveled to America, for what was to have been a three-month fundraising trip on behalf of his monumental undertaking to build Yeshivas Chachmei Lublin. After a large welcome ceremony from leading members of the Agudath Harabonim in New York, the excitement over his visit died down and the great Rav Meir Shapiro was faced with the stark realization that raising the necessary funds to complete the yeshivah was not going to be an easy task.

The following month, the great Torah leader hired himself out to a Brooklyn congregation as a chazzan for the Yamim Noraim, hoping to earn a few dollars and spare himself the embarrassment of having to borrow money for an eventual return trip to Europe.

But in December, help arrived in the form of an old acquaintance from Europe, Rav Ephraim Eliezer Yolles, the rav of Congregation Kerem Israel in Philadelphia, who resided just a few blocks away from Jennie Miller in Strawberry Mansion.

Rabbi Yolles invited Rav Meir to spend some time at his home in Philadelphia, where he promised to help him raise funds. That home, known fondly as the “Beis HaRav,” had a vast Torah library, where the Pietrikower Rav (as Rav Meir Shapiro was then known) felt extremely comfortable.

Rabbi Yolles set out to ensure that Rav Meir would receive maximum exposure and arranged for him to deliver a shiur at Mishkan Israel, the local Talmud Torah for high school age boys, which had been founded by Rabbi Levinthal with the financial support of the Millers.

A few days after that historic shiur, Rav Meir saw his lot change, when Rabbi Yolles accompanied him on a visit to Jennie Miller. The story of this monumental meeting was shared by Rav Meir’s close student and first biographer, Rabbi Yehoshua Baumol, in “A Blaze in the Darkening Gloom” (Feldheim Publications):

Having been advised that the woman (Jennie Miller) was able and willing to help generously, Rav Meir went to visit her; and no sooner was he there, seated in the parlor, than she offered to make a major dedication worth $2,500 for the new building. The Rav, however, gave a slight frown. Sensing a certain displeasure in him, she asked for the reason. Was the amount not enough, perhaps?

In reply, Rav Meir told her of a small incident that happened with him back home, in Piotrków: A certain beggar made his rounds in the city every week, to gather the money he needed to sustain him. Once he knocked on Rav Meir’s door, too, and he walked in to hold out his hand. Without much thought the Rav took out a coin of 50 kopecks and gave it to him — an amount that the beggar could collect ordinarily from perhaps 20 other people.

Well, said Rav Meir to the woman, that indigent beggar didn’t take it, but began to argue and bargain instead. He insisted that 50 kopecks was too little.

Continued Rav Meir: “So I asked him: ‘In the city, you get from one person a twentieth of what I’m giving you, and you take it well enough; you’re satisfied. And here you go and tell me that this is too little?’ He upped and answered me: ‘Honored Rabbi, when I bargain and argue with you, it’s worth my while: because I may get another fine, large coin like this. In town, if I go and argue for more, what will I get? Another kopeck or two? I save my breath and stroll on to the next person. I might as well get my next kopeck from him. It’s easier and quicker than trying to extract it from the first man.’

“You see, then,” Rav Meir explained, “I learned the lesson from that shrewd old beggar: Where I get a small, modest donation, I take it and make no effort to bargain for more. Here, however, I find a dear lady with a Jewish heart that understood my project well enough to give such a large sum directly, as soon as I came in. So it pays for me to try to argue and bargain for more.”

Her response was to pledge yet another $2,500.

Rabbi Yolles then drew up a contract between the two parties and had it countersigned (in what may have been the first major (European) yeshivah dedication negotiated in American history). The detailed contract read as follows:

B”h

Representative of the Sejm

Rabbi Meir Shapiro of Piotrków

Agreement between the representative of Yeshivas Chachmei Lublin and the donor Mrs. Jennie H. Miller from Philadelphia in the presence of Rabbi Ephraim Eliezer Yolles HaKohein.

The representative of the central Torah institution in Lublin, Yeshivas Chachmei Lublin, in the person of Rabbi Meir Shapiro from Piotrków, is hereby obligated to establish the highest class of the Torah Center in the name of Mrs. Miller.

The conditions are:

- The representative is obligated to:

a) Install a proper plaque in the class with all the Jewish and family names that Mrs. Miller will demand.

b) The plaque will also mention the earnings that Mrs. Miller will obtain by supporting the Yeshiva and the amount of her donation.

c) After 120 Years, Mishnayos will be studied in her memory for an entire year and each year on her Yahrtzeit a commemoration will be held, which will be prefaced by the remarks of the head of the class.

2. Mrs. Miller is obligated to:

a) To pay out her pledge of $5,000 in ten monthly installments. Each monthly installment will consist of $500.

b) The installments will be paid with $500 monthly checks on every Rosh Chodesh starting from Erev Rosh Chodesh Shvat and concluding on Erev Rosh Hashana 5688. In exceptional circumstances, the payments can be extended for another two months. In other words, [the full amount should be paid] at the very latest 12 months from today Rosh Chodesh Shvat 5687, January 4, 1927.

Signatures

Rabbi Meir Shapiro

Jennie Miller

Ultimately, in his travels across America, Rav Meir Shapiro visited more than a dozen states, spoke at hundreds of shuls and visited many wealthy prospective donors, but among the $53,000 he raised on the visit, the largest donation was the one he obtained from Jennie Miller.

The author reviews some of his research with Rav Shmuel Kamenetsky

A Very Righteous Woman

The current residents of Jennie Miller’s home had never heard of Rav Meir Shapiro or the other gedolim for whom it was a safe harbor in a foreign land. They surely weren’t aware of the philanthropic largesse of their home’s former owner — but I was about to meet someone who could attest to it firsthand.

It took just a few minutes to reach the Philadelphia Yeshivah; we arrived in time for Minchah, and when it ended, we drove the 95-year old Rosh Yeshivah the three blocks to his home.

Maybe I should have begun with typical niceties, but I was too curious at this point. “Does the Rosh Yeshivah remember a woman named Jennie Miller?” I asked.

Startled, Rav Shmuel turned and faced me. A large smile formed across his face and he exclaimed confidently, “Ah tzadekes gevehn! (She was a very righteous woman).”

I nodded along in agreement. We exited the car and headed for Reb Shmuel’s porch, where we continued the conversation on this beautiful spring day. “Did you know,” Rav Shmuel said, “that she sent 24 different Torah institutions $100 checks each month on every Erev Rosh Chodesh?”

He went on to describe the family’s relationship with Mrs. Miller. “We got to know her toward the end of her life. She gave us a chair that all of the great gedolim sat in when they visited her. Everyone came. Rav Elchonon [Wasserman], Rav Shimon [Shkop], Rav Boruch Ber [Leibowitz]… there is even a picture of the (sixth) Lubavitcher Rebbe sitting in the chair.”

He then invited us inside his home to see the chair. We were introduced to his wife of more than 70 years, Rebbetzin Temi Kamenetsky. “They want to hear about Jennie Miller,” he said with delight.

“Such a choshuve lady!” she said with a smile. “How did you come to hear about her?” Rebbetzin Kamenetsky then showed me a worn Tehillim on the table beside her, which Jennie had given her more than a half-century prior, and she continues to use daily.

I told her about the research we’d done and the visit to Jennie’s former home earlier that day. Impressed, she went on to tell us more about their relationship. We also discussed a detail I’d encountered numerous times — Jennie’s relationship to Rav Akiva Eiger. This was mentioned in several letters from Rav Boruch Ber as well as almost every single letter we have documented from Rav Shimon Shkop, including the blessing offered at the end of this November 1937 dispatch from Grodno to her second husband Nathan Faggen:

She (Jennie) obligates all the wealthy people of our nation with her righteous acts. She is especially notable for the extraordinary fondness she displays in her support of many holy institutions, including our holy Yeshiva, which she supports consistently on a monthly basis. She is the woman whose pure soul emanated from the shining light of the soul of the doyen of geniuses — the great Cedar of Lebanon who encircled the sun with his height; many giants of Israel nested in his branches, and in his shade, they found solace for their weary souls by listening to his original Torah insights whereby he dismantled and resolved (questions pertaining to) the deepest Sugyos (topics in Talmud) and raised precious gems from the depths the Tamudic ocean — namely, the famous genius Rabbi Akiva Eiger, of blessed memory. May his granddaughter, Mrs. Pesha, be blessed with long life and an abundance of goodness, pleasantness, much delight and nachas always.

Shimon Yehuda HaKohein Shkop

(After consulting several genealogists over the course of the last three years, we have not been able to establish exactly how she was a descendant. Perhaps she was descended from a sibling of Rav Akiva Eiger.)

A few weeks later, I made the trip once again with Gavriel — as well as my brother-in-law Dovi Zauderer, — a close talmid of Rav Shmuel — this time to visit Jennie’s kever at the Har Nebo Cemetery, as well as to hear more details about her life from Rav Shmuel and the rebbetzin. Prior to our departure, the rosh yeshivah pointed toward the bookcase.

“We have several seforim here that we received from Mrs. Miller,” he said, “including a few that she received as a gift from the Chofetz Chaim’s rebbetzin. Why don’t you take a look?”

While Rav Shmuel was uncertain as to the exact nature of the connection between the two women, he dropped yet another bombshell: “When Jennie Miller got old and the neighborhood took a turn for the worse, she decided to relocate to a senior community near the shore in Atlantic City. Prior to her departure, she invited us to take whatever possessions remained in her Strawberry Mansion home.”

Letters written by Jennie to Rebbetzin Kamenetsky during the last years of her life have been preserved by the family and offer a vivid description of her feelings:

My dear good Friends,

I received your very welcome letter, and I am happy to hear that you are all well. I am also happy to read Rabbi (Kamenetsky) is busy with the Seforim. That makes me feel very good, believe me.

The big bed on third floor maybe would be good for the Yeshiva. The Green dishes in the breakfast room closet are Fleishig. All the pots and pans in the kitchen big closet are Fleishig. All the dishes in kitchen closet are Milchig. Also in the bottom closet are the Milchig pot and pans.

Yes, it’s a shame to break up such a good Jewish kosher home, but what can I do; it is G-D’s wish for me to be sick and live here (in Atlantic City). For how long I don’t know.

My house is not sold as yet — it will take about 60 days….

(I became melancholic as I read these heartfelt letters of a once regal woman, now ailing and isolated, her words revealing the poignant unraveling of her once vibrant life, and I found myself nodding sadly in agreement as I read the last sentence:)

…It was such a holy home.

Let me hear from you. With best wishes

Yours Always

Sincerely,

Jennie Faggen

Dovi Safier and Gavriel Schuster getting a glimpse of another treasured sefer that once belonged to “The Mother of All Yeshivas”

The Lost Letters

While the Kamenetskys received some of Jennie’s furniture (most notably the chair), the letters did not describe the most valuable possessions that remained in the home.

“In the basement,” Rav Shmuel told us, “there were piles of letters and receipts from all the yeshivos of her time, including her personal correspondence with the Chofetz Chaim, Rav Chaim Ozer, Rav Shimon Shkop, and close to 100 of the greatest gedolim of her time. I did not really appreciate the value of those papers at the time, but it seems that by letting others take them, my family and I lost out on a small fortune.”

Rav Shmuel smiled and added that he had no regrets but figured the correspondence would be of great interest to us. “There are those who still possess these letters — which attest to the incredible respect and admiration that these gedolim had for their benefactor.”

The Rebbetzin reminded Rav Shmuel that the bulk of the letters went to Jennie Miller’s devoted neighbor, Mr. Manfried Mauskopf, a local Talmud Torah principal who had a keen interest in Jewish history. He then nobly did his best to track down the original senders of the letters, but the vast majority of these gedolim, along with their yeshivos, had perished in the Holocaust.

It seems that he donated the rest of the correspondence to various libraries and institutions and in some cases, private individuals — many of whom eventually sold them to collectors and dealers. Little did the great Philadelphia Rosh Yeshivah and his rebbetzin know, but he had just helped us solve yet another mystery.

On our way out, Rav Shmuel asked us if we had any other plans while we were in the area (in his humility, he failed to believe that anyone would travel all the way to Philadelphia just to see him). We informed Rav Shmuel that we had visited Jennie’s kever at the Har Nebo Cemetery and he smiled. “Very nice! A mitzvah! You fulfilled a tremendous mitzvah!”

Then he stopped for a moment and informed us in emphatic fashion, which seemed quite unusual for the soft-spoken leader of American Torah Jewry, “A tzadeikes gevehn; she was a tzadeikes, a true tzadeikes. It’s nisht poshut, not simple.”

Before we had departed, we left Rebbetzin Kamenetsky with a small gift: a thin binder filled with various newspaper clippings and letters we’d found during the course of our research. When I called her a few days later to thank her for her time, she told me that she was particularly moved by one article in an interview Jennie had given to the Exponent when she was honored by Bnai Jeshurun in 1953 at its 36th annual dinner. Clearly proud of “her” Jennie, the rebbetzin began to read to me:

She regularly contributes to the support of more than 40 Yeshivos in the United States and Israel. She supported single-handedly a Yeshivah, now situated in Cleveland, during the years when it was still in Europe. Mrs. Miller now sends out each month more than 50 checks for the support of various charitable, religious and educational groups. Closer to home, Mrs. Miller has made herself responsible for many Jewish families in her home area of Strawberry Mansion. She is a regular supporter of Akiba Academy and the Beth Jacob School.

What manner of woman is this? Perhaps the best way to show her as she is, would be to denote her attitude toward herself and others. Simplicity is the keynote of her life. Despite her outstanding position in communal affairs, she is best known as “Aunt Jen,” a name she prefers to any of the honorific titles she has earned. “Aunt Jen” is extremely religious, a devout woman who davens at home when she cannot come to the synagogue. She is a regular attendant at Friday night and Sabbath morning services. During the time of “Selichoth” (penitential prayers), Mrs. Miller regularly attends the services at five a.m. despite her advanced age.

Mrs. Miller lives alone in an 18-room house in the Strawberry Mansion section. This fact has given to rise to numerous fearful questionings on the part of her friends, as to her safety and health. To one such question, Mrs. Miller replied, “I don’t live alone. I live with G-d.” To a person of such faith, many doubts and fears which assail others of us are unknown.

And this faith has had other effects, as well. It has been said that, without preaching of any kind, Mrs. Miller, has, purely by her own example of Jewish living, been influential in persuading others to join her in her numerous charitable and religious activities.

Rabbi Naftali Zvi Yehuda Riff (1893-1976) was responsible for tens of thousands of dollars that flowed from Jennie Miller to yeshivos throughout the world. He was so beloved in Camden that local gentiles could be heard referring to him as he walked by them as “holy father”

Chapter V: Patroness of the Yeshivah World

IT was clear by now that Jennie Miller was a prolific supporter of Torah learning — but what was the source of her enthusiasm for what at the time was hardly a popular cause? Was it just Rabbi Levinthal?

Yet another lead came via Rav Shmuel, who told us that Jennie had been very close to Rabbi Naftali Tzvi Yehuda Riff, the beloved “chief rabbi” of Camden, New Jersey, situated across the river from Philadelphia. Rav Shmuel suggested that we reach out to his only child, Rebbetzin Rochel (Riff) Gettinger, whom he believed might know more about Jennie.

Rabbi Riff was a scion of the “Bais HaRav,” a descendant of Rav Chaim of Volozhin. During his time studying in the Volozhin Yeshiva, he resided in the home of his grandfather, the Rosh Yeshivah Rav Raphael Shapiro, son-in-law of the Netziv. After marrying his wife Basya (a descendant of Rav Yitzchok Elchonon Spektor), he then took a rabbinic position in Telechin.

Upon his move to America, Rabbi Riff’s leadership impacted far beyond the Camden/Philadelphia area. He served as the vice president of the Agudath Harabonim and was instrumental in the Vaad Hatzalah. However, Rabbi Riff is best remembered for his decades of tireless work on behalf of Ezras Torah where, as successor to Rav Yosef Eliyahu Henkin, he became the source of salvation and sustenance to thousands of bnei Torah across the globe .

The mere mention of the town of Telechin piqued my curiosity. Where had I recently come across it? A swift search through my files revealed the answer to another enigma. In 2022, I had the chance to discuss the Jennie Miller story during a Shabbos meal with Rav Binyomin Carlebach, a son-in-law of Rav Beinush Finkel and one of the current roshei yeshivah at the Mir Yeshivah in Yerushalayim. That serendipitous conversation led to an astonishing discovery.

Mr. Manfried Mauskopf, the aforementioned Talmud Torah principal who had received most of Jennie’s correspondence following her move, sent the Mir Yeshivah a package containing 150 pages of correspondence between the Mir roshei yeshiva and Jennie. The cover letter, dated January 3, 1968, read as follows:

Mirrer Yeshiva

Jerusalem, Israel

Dear Sir,

I am sending you the enclosed letters which were originally written before the war when your famous institution was still located in Europe. I believe you might be interested in them for historical and sentimental value.

Manfried Mauskopf

This correspondence began a month after Jennie’s initial meeting with Rav Leizer Yudel Finkel and Rav Avraham Kalmanowitz in 1928. The exchange started with an agreement to establish the “Jennie Miller Kollel” at a cost of $120 per month, a sum that would support ten “rabbinic scholars” in their studies at “The Holy Yeshivah of Mir.”

What caught my attention were two letters written six years later, in 1933, which mention Jennie’s request that the Mir assist two bochurim from Telechan, Eliezer Kobrir and Zev Katarinsky, who hoped to gain acceptance to the yeshivah. I had previously wondered why Jennie was particularly interested in these students. Were they family members? Now, however, I had my answer.

Apparently Rabbi Riff had utilized Jennie’s special connection with the Mir roshei yeshivah to ensure that his former landsleit would receive special treatment. Today it’s all too common for a hopeful student to require “pull” in order to be accepted into an elite yeshivah, but this letter appears to be the first documented case of an American balabos (in this case, a balabusta!) using her influence to arrange admission to a Lithuanian yeshivah.

Bottom row, from left to right: Rav Reuven Levovitz (nephew of Rav Yerucham Levovitz), Rav Avraham Kalmanowitz, Rav Leizer Yudel Finkel, Rav Isaac Sher (Rosh Yeshivah of Slabodka), and Rav Zalman Permut (Menahel of Kovno Kollel)

Top row, from left to right: Rav Kotzultzki (Menahel Misrad of Slabodka), Rav of Vilna, Rav Moshe Yitzchok Mendelowitz, Rabbi Nissan Waxman, Rav Yosef Adler, and Rav Avrohom Chinitz

“She Had Very Good Taste”

Rabbi Riff’s appointment as rabbi of Camden came via the recommendation of Rabbi Bernard Levinthal, who would later write in a tribute article that he seized the opportunity to bring this “unusual personage” to the Philadelphia area and benefitted greatly from working alongside him for more than 25 years.

(In yet another testament to Rabbi Riff’s greatness, Rav Shmuel Kamenetsky’s children recalled how during their early years in Philadelphia, their parents would take them to Camden to visit the Riff home on Erev Yom Tov to receive a brachah from Rabbi Riff.)

Many decades had passed since Rabbi Riff’s passing, but I hoped that his only child could piece together his connection to Jennie Miller. I was able to reach Rebbetzin Gettinger on the phone that afternoon at her daughter Sarah Ungar’s home in Chicago.

When told of the nature of my call, Rebbetzin Gettinger became excited. She still remembered those visits to Strawberry Mansion with her father in the 1930s, and told me that Jennie had been “a charming woman and a very generous American patriot. She lived in what — at that time — was the aristocratic section of Philadelphia, where there weren’t too many Orthodox people. She was very much influenced by my father to become a big supporter of Ezras Torah and other important (Torah) causes.

“She was the very special type,” Rebbetzin Gettinger continued. “She was the kind of woman who entertained great rabbanim at her home and then would have a chauffeured car take her and her husband to the opera. She was very hospitable. She was particularly interested in supporting talmidei chachamim and their families. She had very good taste in that sense. She was very friendly, in a stately sort of way.”

Jennie certainly appreciated Rabbi Riff as an advisor and mentor, and took his suggestions very seriously. Page through the solicitations and letters sent to Jennie from the various roshei yeshivah and you will repeatedly see Rabbi Riff’s name. Clearly, he was a key conduit between the yeshivos and their donor in Philadelphia.

In 1931, the Ponevezher Rav wrote to Jennie, “Rav Riff from Camden came to visit the Yeshiva and conveyed personal regards from you and your husband. He was shown the building that was bought for Beis Hayeshiva by Pesha bas R’ Yisrael.”

A letter from Rav Avigdor Menkovitz and Rav Mordechai Zev Dzikansky from Yeshiva Ohr Hachaim (the original yeshivah ketanah in Slabodka founded by Rav Tzvi Hirsch Levitan in 1869) dated August 3, 1933, reads: “Rabbi Riff wrote us that to our great regret and sympathy, you lately lost a lot of money. Nevertheless, knowing the great need… of the Yeshivah… your heart was moved like the heart of a true mother of Torah study. You overlooked your own losses and sent your donation for the past four months.”

Another letter sent from the Radin Yeshiva on Tu B’Shevat of 1932 and signed by the Chofetz Chaim thanked Jennie for her $26 donation that month and asked for the yahrtzeits of her parents, “which will surely be observed when we are informed of the exact names and dates. We hope Rabbi Riff from Camden will write us about this.”

There is also a 1932 letter from Kelm written by Rav Daniel Movshovitz and Rav Gershon Miadnik that references Rabbi Riff as the person who recommended their yeshivah to Jennie, as well as a missive from the editors of a Sefer Hayovel being written for Rav Shimon Shkop which requests that Jennie send them Rabbi Riff’s address.

The revived Telshe Yeshiva under Rav Elya Meir Bloch and Rav Chaim Mordechai (Mottel) Katz in Cleveland continued to benefit from Jennie’s largesse

Not only did Rabbi Riff describe the yeshivos and their leaders to Jennie Miller, he would also introduce them to her in person during their visits to Philadelphia.

Rabbi Riff’s grandson, Rav Raphael Moshe Gettinger, shared with me an incredible story about Rav Boruch Ber’s visit to Philadelphia in 1929, part of an 18-month-long trip to America along his son-in-law Rav Reuven Grozovsky, during which he raised a total of $35,000 to cover the yeshivah’s debts.

As was the tradition, Rabbis Levinthal and Riff arranged for Rav Boruch Ber to deliver a shiur to local community leaders and rabbis at the local Yeshiva Mishkan Israel, after which an appeal for the Kaminetz Yeshiva would be made by Rav Reuven.

Rabbi Riff shared with his grandson, Rav Rephhael Moshe Gettinger, vivid memories of Rav Boruch Ber dazzling the packed building with an intricate shiur on the sugya of areivus (guarantorship) in Masechas Bava Basra (this classic shiur of Rav Boruch Ber is included in his sefer Birkas Shmuel). As Rav Boruch Ber dove into an intricate examination of the different types of cosigners mentioned by the Gemara, Rabbi Riff sat there admiring Rav Boruch Ber’s genius — for this was the perfect setup for a grand-slam fundraising pitch. Rabbi Riff readied himself for what he assumed was the foregone conclusion to the shiur: “Kol yisrael arevim zeh la’zeh, who are the areivim (cosigners) for the bnei Torah back in Europe? It is you, their brethren in America!”

Rav Boruch Ber, however, had other ideas. The fundraising pitch never came. Rav Boruch Ber would never dream of “tarnishing” such a pristine shiur with talk of money. Instead, it was up to Rav Reuven to try and salvage the evening with an appeal of his own.

Rabbi Riff then made sure to help Rav Boruch Ber by personally accompanying him on his appointment with Mrs. Miller later that week.

Samuel Daroff, President of Bnai Jeshurun and the son of a wealthy Volozhin graduate Harry Daroff, participates in the distribution of matzos in Strawberry Mansion before Pesach. Such local tzedakah projects were extremely important to Jennie — and she devoted much of her time to developing and fostering them

Commanded by Rav Chaim Ozer

Sometime later, Rabbi Riff once again traversed the Delaware River in a taxi across the brand-new Benjamin Franklin bridge to pay a visit to Mrs. Miller. His heart was pounding in his chest, for this time was different. Rabbi Riff had been instructed by the gadol hador, Rav Chaim Ozer Grodzenski himself, to seek urgent assistance for the Ramailes Yeshiva, which was teetering on the brink of financial ruin.

Normally, Rabbi Riff would make an appointment with Mrs. Miller before visiting her, but this was an emergency. Rav Chaim Ozer had sent a telegram with strict instructions to act immediately. Rabbi Riff wondered how he would explain the gravity of the situation. Just a short while before, he had introduced Rav Boruch Ber Leibowitz as the greatest Talmudic scholar of his time. How could he now convey the towering stature of Rav Chaim Ozer, the leader of world Jewry?

As he approached Mrs. Miller’s home, he saw her stepping out of her house and getting ready to enter her limousine. His heart sank; he had no choice but to act quickly.

“Where are you headed?” he blurted out, unsure of how to begin. Mrs. Miller replied that she was going to a show. Without thinking, Rabbi Riff quickly said, “Don’t you know that it’s Sefiras Ha’omer, which is a time of mourning for the Jewish people and we don’t attend the theater.”

Mrs. Miller was taken aback. She turned to her driver and said, “John, put away the car, we are not going to the theater today — the rabbi says that it’s better for us not to go.” She then invited Rabbi Riff inside and offered him his usual glass of tea.

They engaged in a brief discussion, and Rabbi Riff made his pitch on behalf of Rav Chaim Ozer, highlighting the stark difference between the two Torah giants of the era.

Mrs. Miller listened attentively to his appeal and then replied, “Of course, dear rabbi, I will make a generous donation. Thank you for your visit!”

The Ramailes Yeshiva would survive, thanks to Mrs. Miller’s generosity and his quick thinking.

As I shared with Rabbi Gettinger the story of the Telshe brochure that had originally alerted me to Jennie Miller, he was reminded of yet another story he’d heard from his illustrious grandfather.

When Rav Elya Meir Bloch and Rav Mottel Katz escaped from Telshe to America in 1940, they sought a suitable place to open up an American branch of the yeshivah. As part of their efforts, they visited Rabbi Riff in Camden.

At some point during the conversation, Jennie Miller’s name was mentioned and the Telzer roshei yeshivah began to describe how the yeshivah and the local economy back in Telshe relied heavily upon the great Philadelphia philanthropist: “Credit was extended to the yeshivah by local vendors for food and other supplies by virtue of the fact that everyone knew exactly when the monthly allotment from Mrs. Miller would arrive. So much so that if the yeshivah were ever late paying bills, the local merchants would complain, ‘What is going on with the American woman? When do you expect her money to arrive?’ ”

Suddenly, I recalled of one of the first stories that Rav Shmuel had told us about Jennie, back on our first visit to his home:

Every month, on Erev Rosh Chodesh, come rain or shine, a resolute Jennie Miller set out on the short trip from her palatial home on North 33rd Street to the post office at 19th and Oxford Street in the heart of Strawberry Mansion. She carried a handful of postal money orders, lifelines to the Torah institutions across Eastern Europe, Mandatory Palestine as well as a growing list of institutions in America.

By now, she could practically repeat the list of recipients by heart. Mir, Telshe, Ponevezh, Slabodka, Radin, Grodno, Kelm, Chachmei Lublin, Mesivta of Warsaw, Etz Chaim, Merkaz HaRav, Torah Vodaath, RJJ….

Each received monthly donations varying from a modest $10 to a generous $500. To these institutions, Jennie’s support was more than just a kind gesture; it was the sustenance that kept their doors open, lights on, and students fed.

In return, the yeshivos were quick to acknowledge the timely arrival of these vital funds. Their gratitude, evident in the fervent letters they sent back, was a testament to the importance of Jennie’s unwavering commitment. For them, her punctuality was not only a sign of generosity but also a demonstration of the compassion that bound them together. Her sensitivity towards their plight was evident in the two times a year she visited the post office a few days early, the days prior to Tishrei and Nissan when funds would be needed to pay for Yom Tov necessities.

But even heroes have their moments of weakness. One fateful day, Jennie arrived at the post office just as the last rays of sunlight were disappearing behind the horizon. In her haste, she realized that she had left her money at home. Her heart sank, her eyes filled with tears, and the weight of her mistake threatened to crush her spirit. She imagined the thousands of students in the yeshivos she supported, their hunger gnawing at their insides, all because of her error.

The teller at the post office noticed Jennie’s distress and with a reassuring smile, offered to advance the funds for her, trusting that she would return the next day to make amends for the overdraft — an unheard-of act during the days of the Great Depression. The teller’s gesture was more than a simple act of kindness; it was a testament to the impact of Jennie’s devotion on those who crossed her path.

Chapter VI: Loss and Light

When Harry Miller passed away in 1923, he left his widow with an exorbitant amount of money. But, as Rav Shmuel had alluded during our first visit, a major issue arose. Since the Millers did not merit any children, Jennie could not remarry without first undergoing chalitzah. This should have been a fairly simple halachic procedure, except it seems that Harry’s brother decided that his now wealthy sister-in-law’s religious obligation was his ticket to prosperity.

On every visit I made to Philadelphia, Rav Shmuel emphasized the rare piety of Jennie, mentioning this episode as perhaps the most glaring example: “Her brother-in-law refused to go ahead with the chalitzah unless she agreed to pay him $150,000! Do you know how much money that was in those days?”

In January 1929,ֶ following the chalitzah ceremony, Jennie married for a second time. Her new husband, the 56-year-old widower Nathan Faggen, was an influential Philadelphia businessman who had come to America from Chernigov (current day Ukraine) as a 15-year-old in 1888. He opened a shirt-manufacturing business along with his wife’s family, the Tuttelmans, but eventually went off on his own and opened the Lomar Manufacturing Company, which primarily manufactured men’s sleepwear. A local newspaper wrote that “He was among the first to popularize pajamas among Americans, who had previously retired to sleep in nightshirts.”

More importantly, he shared Jennie’s appreciation for communal work, serving as the president of Bnei Jeshurun as well as the president of the local Vaad Hakashrus and the Yeshiva Ohel Moshe. He also began a regular chavrusa with Rabbi Riff.

We knew from the chalitzah episode as well as other sources that Jennie never had any children of her own. But both Rebbetzin Kamenetsky and Rebbetzin Gettinger alluded to a tragic loss of a child that Jennie suffered during her lifetime, which changed her forever. I assumed that the loss was probably one of her stepchildren via Nathan Faggen (who had six children from his previous marriage), but I was soon to learn otherwise.

In Cherished Memory

The exact nature of Jennie’s life-changing loss was unveiled in an obituary and a series of news stories that ran in the Jewish Exponent in November 1929, regarding 11-year-old Cecelia Cohen. According to a great-niece that I interviewed, Cecelia (Tzirel) was a niece Jennie had “adopted” in infancy and raised as her own. It is unclear how or why that happened, but it seems to have been a gesture of love from her brother Samuel, who’d been blessed with four children of his own and watched his childless sister suffer in her grand, empty home.

This same great-niece (who vividly recalled Jennie from her childhood) shared that her grandfather, Jennie’s brother, was unemployed for a time, and Jennie would send her driver to his home every week to take the family shopping for groceries and occasionally a show.