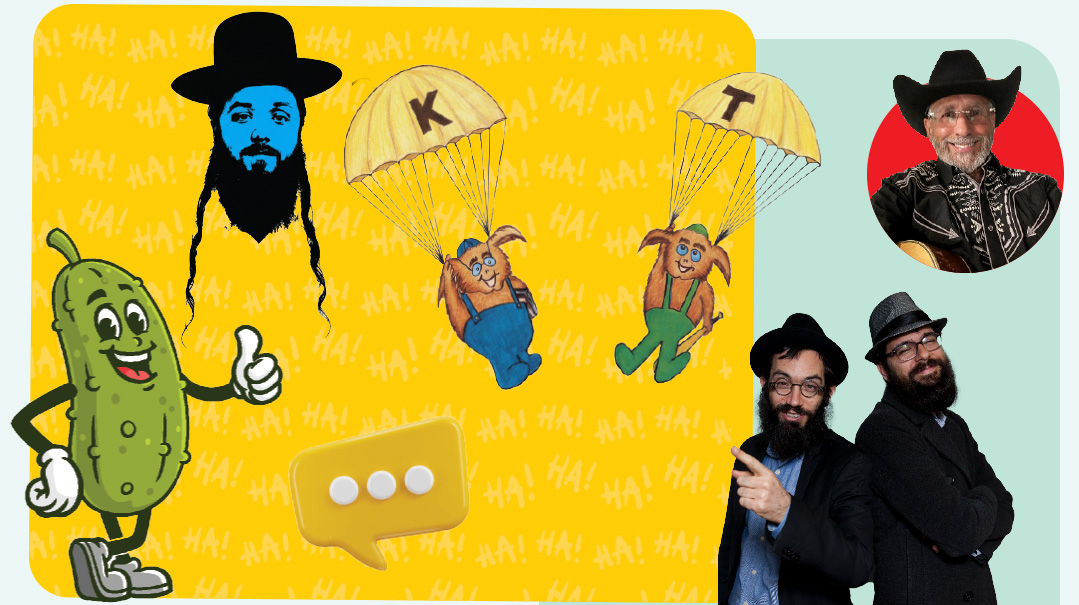

Mood Mix with Moshe (Moussa) Berlin

| May 2, 2023Clarinetist Moussa Berlin tunes up for another Lag B’omer on the bandstand

For over 60 years, MOSHE (MOUSSA) BERLIN has been the face of the music in Meron and is considered Israel’s top preserver of the klezmer tradition. In 1973 he succeeded Avraham Segal, the klezmer hero of his youth, as the lead clarinetist for Lag B'omer. Moussa held a day job as a software engineer until about 30 years ago, when he decided to devote himself to being a full-time musician.

HOW I GOT STARTED IN MERON

The first time I came to Meron on Lag B’omer was 71 years ago, in 1952. I was about bar mitzvah age and I can’t remember all the details of the visit, but it surely made a strong impression, because I’ve continued to go every year since. Around ten years later, once I was already playing clarinet, I joined the musicians on the bandstand, and in the 60 years since, playing at Meron has been a constant for me. I was entranced by the original Meron musicians of the 1950s, Avraham Segal and his family, who were an extremely musical bunch. Their instruments were only clarinet, drums, and cymbals, yet somehow, they played for 24 hours, more or less, without stopping.

The music they played depended on people’s requests. Back then, when someone wanted a certain niggun, he would come up to the bandstand and make a request, not by naming it, because those types of tunes did not have official names, but by singing it himself. He would then pay the musicians, and they’d play it, while he danced up a storm of joy and elevation. There were some niggunim that were very popular, and over the years, the niggunim were named according to those who regularly requested them, so that they became known as “Elenshtein’s niggun,” or “Shefer’s niggun.” Other than the few lirot the celebrants handed them, the Meron musicians weren’t paid, because no one had actually booked them. They were drawn there of their own accord.

WHERE MERON MUSIC COMES FROM

Wherever Jews come from. There’s a lot of musical influence from Middle Eastern Jews. In the years gone by, the music of Turkish, Lebanese, and Iraqi Jews has come to Meron and has gotten added to the Meron playlist.

HOW THINGS CHANGED

In the beginning, the other musicians were much older than I was, but by now, of course, I’m senior musician. I still play at Meron, but not for 24 hours straight. I have my corner and I play the traditional music, trying to keep the sound of tradition alive. Any changes I make have been gradual, not drastic modernization.

In general, the experience of Meron, and its music, has become diluted. I see it this way: In earlier years, there were no recordings of Meron on Lag B’omer. The only way to be there was to be there. You came, and you imbibed and absorbed the experience to the maximum. If you didn’t utilize those moments you’d lose out, and wouldn’t get it back until next year, so it was all much deeper and stronger. Nowadays, everyone is busy recording Meron to take it home with them. You can sit at home and watch and listen to Meron any day of the year. But that lessens the intensity of the experience. As one of my musician friends expressed it, “Once, everybody danced at a wedding, and one person took pictures. Today, everyone takes pictures, and one person is dancing.” But less dancing means less joy.

THE BEST MOMENTS AT MERON

It’s hard to define “best,” but whenever a tzaddik or an adam chashuv comes into the circle, the fervor and joy of the dancing increases. There are emotional moments, too — the three-year-olds with their freshly clipped hair on their fathers’ shoulders, accompanied by the traditional Meron klezmer tunes for these chalakahs.

And it was always special for me when one of the big rebbes from Yerushalayim who liked my music would stop next to the bandstand in the courtyard for a few minutes to listen before making his way to the kever.

HOW I LEARNED CLARINET

I learned to play by ear. I listened to the music of Meron and elsewhere, and played what I heard. Later on, I also listened to many klezmer records from Europe. Until today, I don’t use music notes. I live my music and play it very spontaneously, never rehearsing a playlist in advance, and only preparing mentally what I’m going to play if it’s a concert or festival gig. Even then, I sometimes change things around at the last minute. HaKadosh Baruch Hu sends me the right niggun for the right moment in real time.

ANOTHER INSTRUMENT I’D LIKE TO PLAY

When I was a child, my parents sent me to learn violin, but I didn’t connect to it. Instead, I taught myself clarinet using books and experimentation. For a time, I wanted to play the saxophone, too, but in the end, I stayed with the clarinet. It’s very versatile, and at this stage of my life I’m not looking to add anything else.

MUSIC I LIKE TO LISTEN TO

All kinds. I don’t play when I’m alone, but I listen to classical music, Israeli music, and chazzanut.

THE REQUESTS I SAY NO TO

If I don’t know it, I can’t play it. But the truth is that I also decide if the music someone is asking me for is suitable for that moment. At weddings I have been asked to play Yiddish songs, even Greek songs or Irish folk music, and I’m always happy to comply with special requests — if I feel they fit the mood of the moment.

IF I HAVE A CHOICE BETWEEN A SYMPHONY AND A SMALL BAND

Small! I can’t play with more than five or six players. I used to lead a small group called Sulam, and the musicians were Roman Konsman a”h, Leib Yaacov Rigler, Meir Rosen, and Menachem Herman. We understood each other, and each contributed from his own professional and musical background. One brought elements of jazz, another classical harmony. We played at many events and festivals, always spontaneous — no rehearsals needed — and always beautiful professional music. My daughter and my son are also musicians, and we view music as a means to understand a person and bring him up from materialism to a more elevated state.

A SONG GONE OUT OF STYLE THAT I’D LIKE TO BRING BACK

There are many, but I can’t play a song that listeners don’t know and can’t connect to, so it’s very difficult to bring a song back. I think the radio hosts, when they select old music and replay it often enough, are the ones who can actually bring back old songs.

THE MUSIC I PLAY

While I play chassidic music as well — the music of Modzhitz, Gur, Vizhnitz, Breslov, and Boyan, most of the music is klezmer music. But there’s a difference between the traditional klezmer music of Eretz Yisrael and the klezmer tradition of the Diaspora. Klezmer in Meron, for example, is a uniquely authentic tradition that has continued without a break, passed from one musician to another. In Europe, the Jewish music, including klezmer culture, was completely cut off by the Holocaust. It then became necessary to research it and revive it, so it’s automatically less authentic. Another difference is that the klezmer of the Diaspora has more minor notes, meaning there’s a certain melancholy. What we play here is happier. But that’s easy to explain — living in Eretz Yisrael brings a deep level of inner joy, and there was a lot of Jewish suffering in the Diaspora. Of course, underneath that klezmer melancholy there was also optimism, because Judaism has integral optimism despite the suffering.

A SONG THAT’S IN MY HEAD

I always have a song in my head, sometimes the same one for a while. I think that Hashem sends me these songs to give me koach and express my mood. There were times when Bentzion Shenker’s niggun for “Ohr Chadash al Tzion Ta’ir” was always with me. I loved it.

EXPECTATIONS FOR MERON THIS YEAR

Since the tragedy, things are very different. The feelings are very difficult. Frankly, I don’t know what Meron will be like this year. I am optimistic that the rejoicing of Meron will return soon, but I think that we are past the stage of having one huge celebration. Baruch Hashem, the community is very large, and the site is simply too small. Instead of one hadlakah, there will be several separate locations and hadlakot. Each one can be special and even intimate, but we can’t go back in time to have everyone together.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 959)

Oops! We could not locate your form.