Monumental Debate

| June 27, 2023“...The Jewish mind does not recognize anything praiseworthy in the erection of not useful and salutary, although magnificent structures”

Title: Monumental Debate

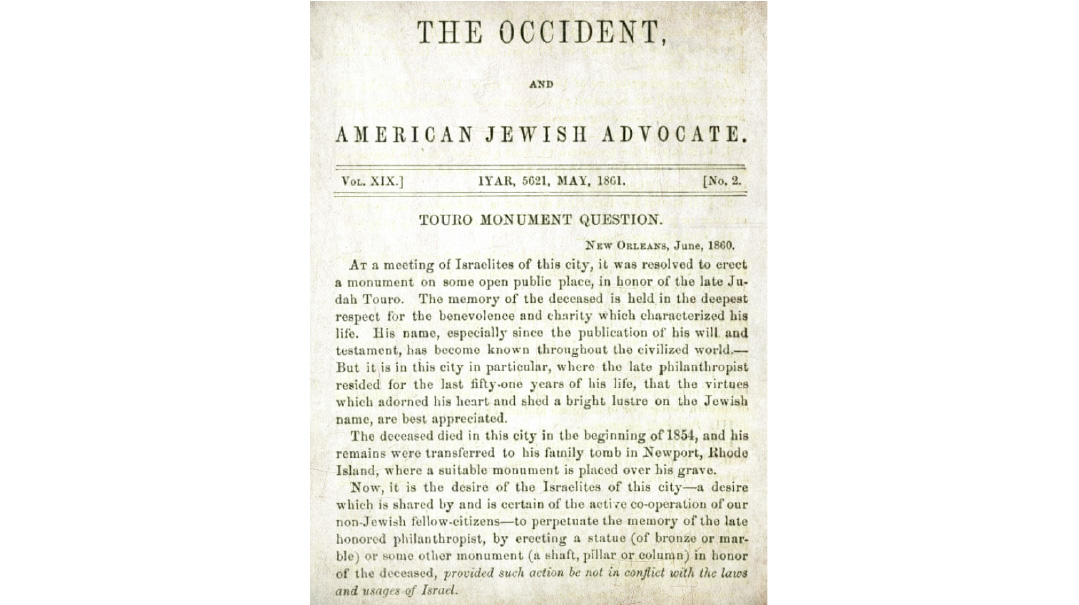

Location: New Orleans

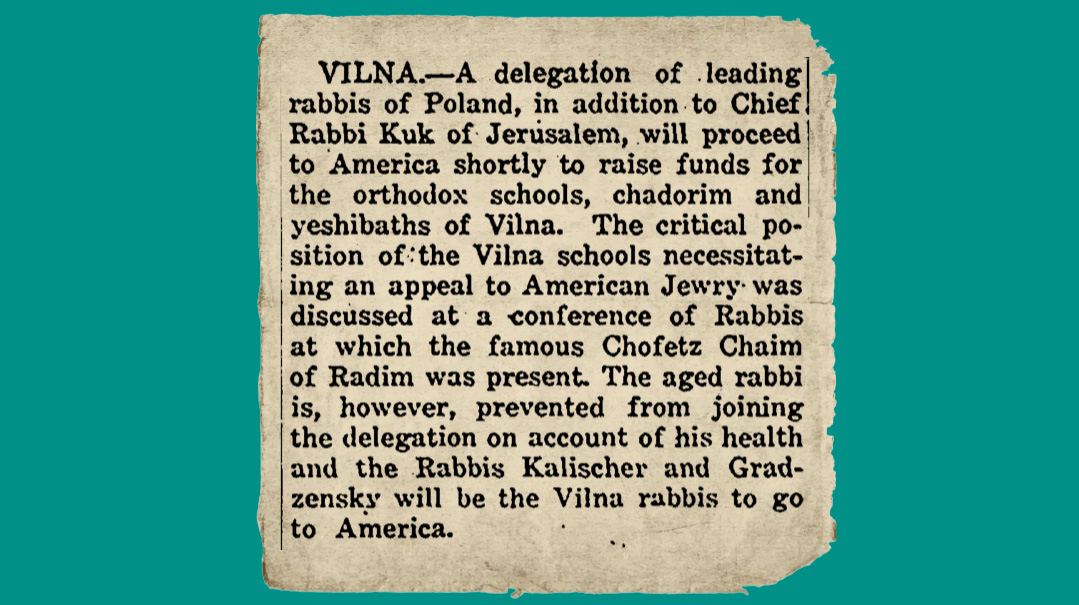

Document: The Occident and American Jewish Advocate

Time: 1860

As Israelites and American citizens, we deem it a sacred duty as well as a proud privilege to testify in an enduring form our respect, admiration and gratitude in which we hold the memory of our late benevolent and patriotic fellow citizen, Judah Touro.

—The Touro Monument Association, June 1860

Judah Touro was born in 1775 into a prominent Sephardic Loyalist family in Newport, Rhode Island. He grew up in Jamaica and Boston, and moved to New Orleans in 1801, remaining there for the rest of his life. He amassed a fortune through ventures in commerce, shipping, and real estate investment. Despite his eccentricities, indecisiveness, and unique personality traits, the lifelong bachelor was known in New Orleans for his simple lifestyle, integrity in business, and philanthropic endeavors. In his later years, he renewed his commitment to Judaism, regularly attending Shabbos services at the Sephardic-Portuguese Nefuzoth Yehuda Synagogue. In 1854, he died heirless and willed a considerable part of his estate to Jewish institutions.

A few years after his death, some New Orleans citizens organized to erect a monument to Judah Touro’s memory, but the initiative faced opposition from a number of rabbis throughout the country, who asserted that Judaism forbade the creation of any graven image.

A fascinating account of this opposition can be found in the chronicles of Yisrael ben Yosef Binyamin, a 19th-century itinerant writer known by the pen name Benjamin II who modeled himself after Benjamin of Tudela, the famous medieval Jewish traveler. When Benjamin II arrived in New Orleans in April 1860, he was well received by the Jewish community. However, upon learning of the proposed Touro monument, Benjamin II objected, stating that the creation of a statue was clearly forbidden by halachah. His public protest against the monument led to a debate in the community that grew so heated that the visitor had to flee the city.

The community ultimately decided to consult rabbinic authorities in Europe. James Koppel Gutheim, acting president of the Touro Monument Association, wrote to Chief Rabbi Nathan Adler of London, Rav Shamshon Raphael Hirsch of Frankfurt, Rabbi Shlomo Yehuda Leib Rappaport (Shir) of Prague, and Dr. Zechariah Frankel of Breslau requesting their opinions on the matter. Their unanimous decision was that the erection of such a statue was not permissible.

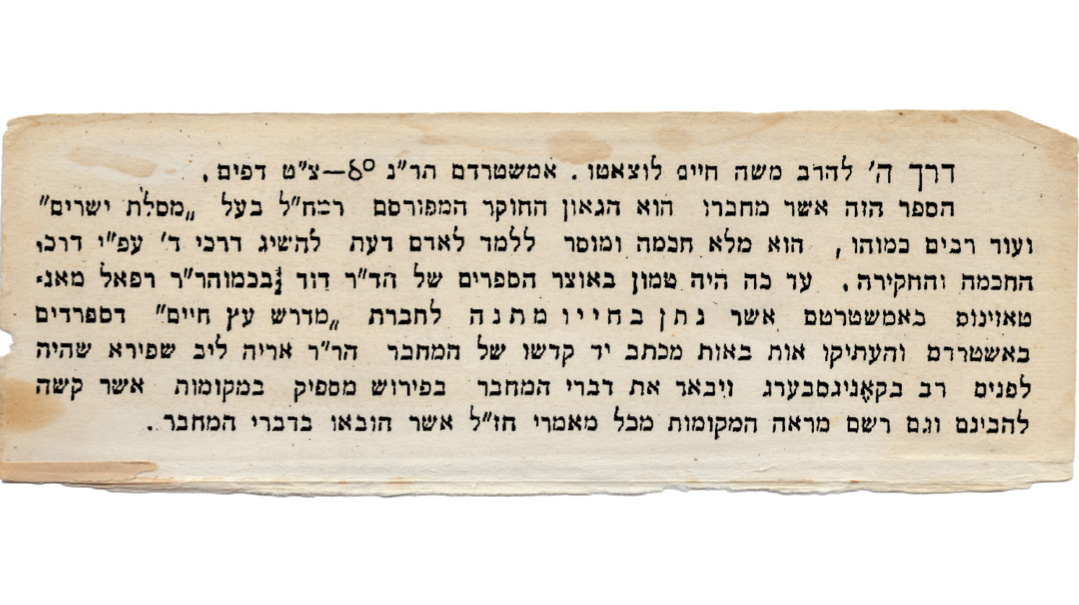

Rav Hirsch’s eloquent response was reprinted in full in the Occident newspaper as well as in Benjamin II’s book. Following a scholarly summary delineating the halachic parameters of the prohibition, Rav Hirsch ended with a resounding lesson in Jewish values:

Let us not forget that the Jewish mind does not recognize anything praiseworthy in the erection of not useful and salutary, although magnificent structures.

A rabbi who, on passing a magnificent synagogue, boasted, “Kamah mammon shok’u avosai kan — How much money have my fathers sunk here?” received a reply, “Kamah nefashos shok’u avosecha kan — How many souls have they sunk here! Lo haveh bonim dilin be’Oraisa — Were there no people in need of assistance to enable them to study the law?” [Yerushalmi, Shekalim 5:4]

And thus I believe, honored sirs, will you perhaps share my conviction, that were you to devote, in honor of the name of the deceased, the interest of the amount which the erection of a monument would cost toward the annual bestowal of a physical, intellectual, or moral benefit upon a single human soul, you would honor his memory, the more he was actually deserving such honor, in a more Jewish, i.e., truer and worthier manner, than by the most magnificent monument which you may execute in bronze or marble.

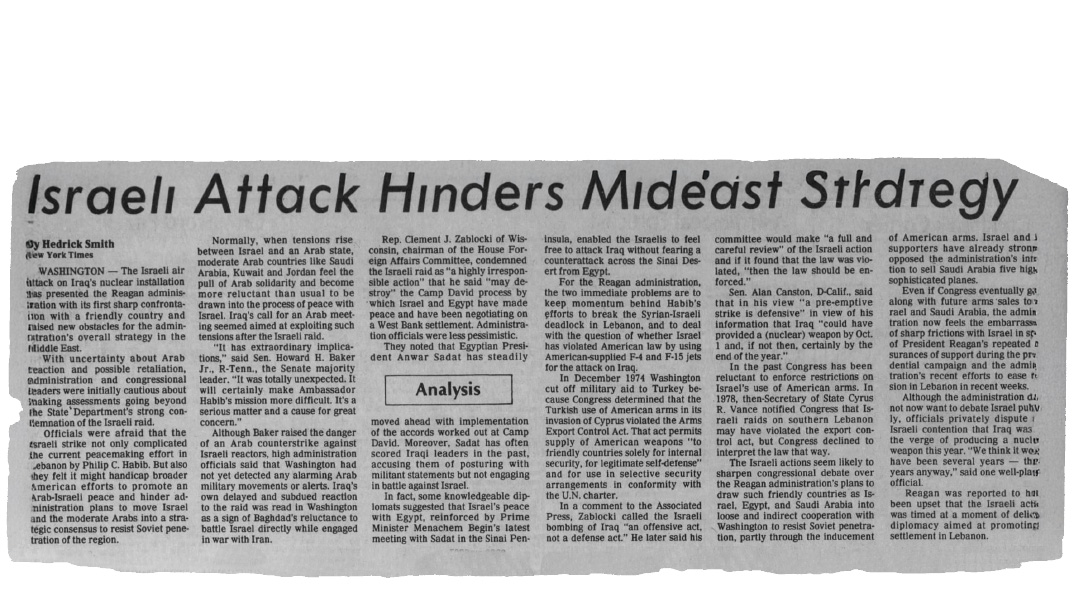

In the end, the monument was never built. Benjamin II writes: “At this time, the Civil War in America broke out and ‘the L-rd annulled their decision and made their purposes in vain.’ Although, because of this affair, I suffered much and had great losses, nevertheless, I had the satisfaction of having acted according to my convictions and of having opposed, not without success, a memorial so public, so enduring and so un-Jewish.”

Patriotic Philanthropist

During the War of 1812, Judah Touro volunteered as a private in the Louisiana Militia under General Andrew Jackson, where he was wounded by a cannonball in the Battle of New Orleans. News of his injury reached his friend and fellow merchant Rezin D. Shepherd, who left his post, carried Touro to his house, and hired nurses to care for him, thereby saving his life. Touro never forgot his savior and made him one of the largest beneficiaries of his will.

The Forgotten Benefactor

Among the many beneficiaries of Touro’s remarkable will was a $50,000 fund to help “ameliorate the condition of our unfortunate Jewish brethren in the Holy Land.” The first neighborhood built outside Jerusalem’s Old City walls in 1860 was Mishkenot Sha’ananim (later absorbed into Yemin Moshe). While the initiative is generally attributed to Sir Moses and Lady Judith Montefiore, the funding came from Touro’s will: “I wish to support the endeavors of Sir Moses Montefiore in his efforts to assist the poor of the Holy City of Jerusalem.”

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 967)

Oops! We could not locate your form.