Monsey’s Secret

Reb Shmelka Taubenfeld didn’t head a prestigious yeshivah or author best-selling seforim, but it was he who gave the entire chaburah its pride and prestige

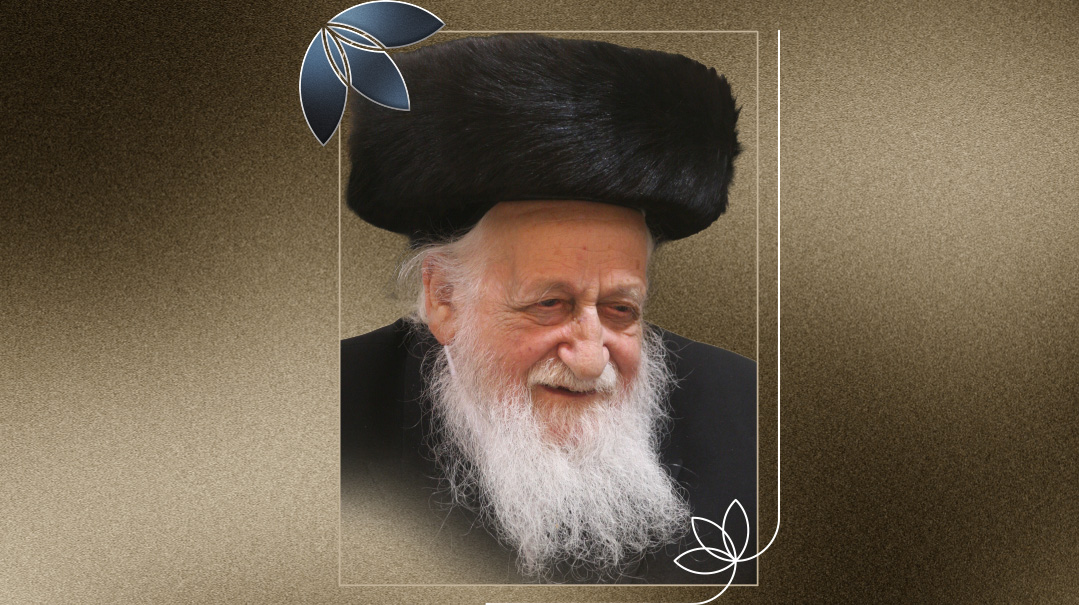

We grace our walls with images of gedolim, men who shaped future leaders, wrote famous tomes, inspired and taught the masses. Rav Shmuel Shmelka Taubenfeld was a different kind of gadol: He lived in relative isolation, far from the public eye, and his only pursuit was Torah — more and more learning. But the people he touched, while relatively few, will forever carry his memory.

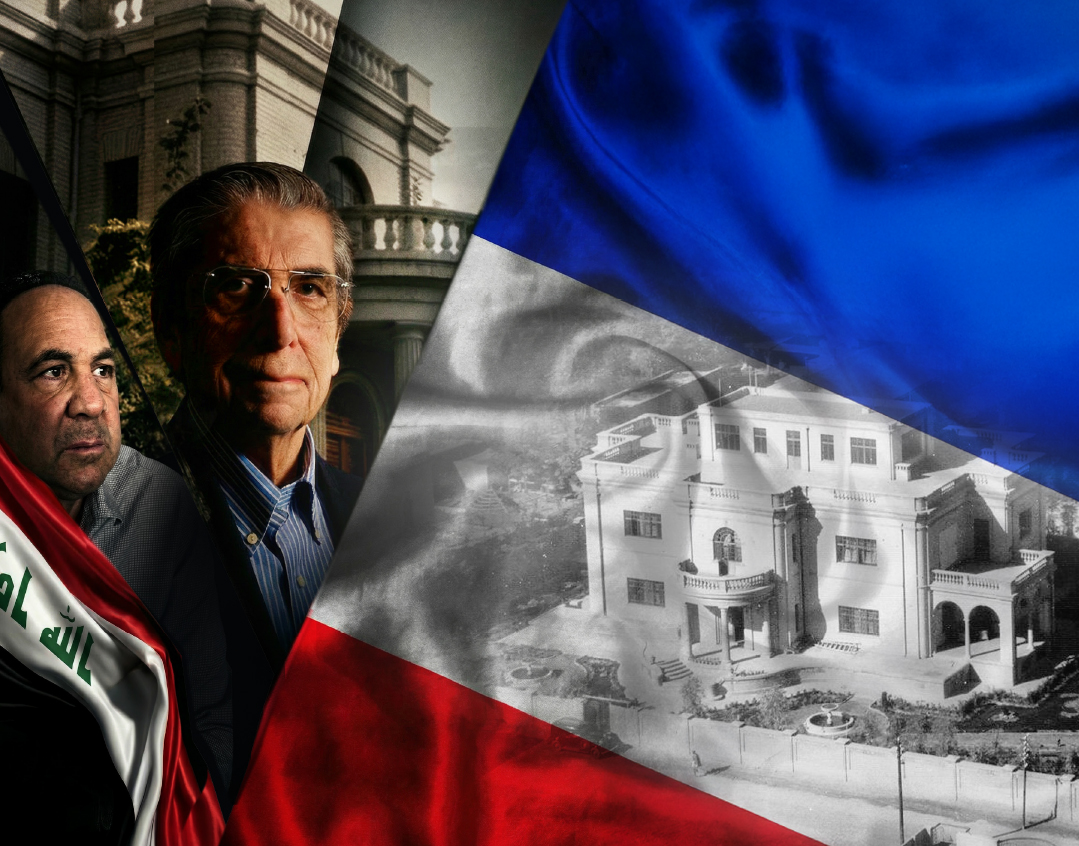

Walk up Monsey’s Route 306 where it intersects with Route 59 and savor the options: sushi or prime cuts of meat, upscale cafés or ice cream in a dazzling array of flavors. You can turn right, left, or go straight in Monsey, a capital of contemporary heimeshe gastronomy.

Sixty years ago, this very intersection was already a capital. Back then, it also featured diversity, breadth, and range, an incredible assortment of options, though not of the edible sort. Food was fairly limited — fresh baked goods imported from Brooklyn — but the tiny settlement boasted an assortment of unique gaonim. And like a gleaming display case in an epicurean heaven, it featured all sorts of scholars: some proficient in all of Shas, others capable of hairsplitting analysis. The penetrating self-awareness of Reb Yerucham’s mussar fused with the crackling warmth of Reb Shraga Feivel’s chassidus; there was room for everything in the display case that was the humble beis medrash of Beth Medrash Elyon, breeding ground of gedolim.

If you slip through the trees of Main Street, between the rustling leaves of Elyon Court, you can still see the old building, the rocks upon which Reb Shraga Feivel sat, talmidim at his feet, and shared mysteries of creation, the humble bungalows from which the first generation of kollel couples in America taught those that would yet come what the lifestyle demands.

And with a bit of imagination you might discern the impression left by a unique figure, humble in stature, carriage, and title while towering in genius and kindness.

Reb Shmelka Taubenfeld didn’t head a prestigious yeshivah or author best-selling seforim, but it was he who gave the entire chaburah its pride and prestige. His story, largely untold, is the coming-of-age tale of the American Torah world.

KELM IN ROCKLAND COUNTY

After Reb Shraga Feivel Mendlowitz’s Torah Vodaath succeeded in producing the bnei Torah that would give America its first generation of balabatim, the visionary menahel perceived the need for a higher level yeshivah, where the elite talmidim could continue on and give America maggidei shiur, dayanim, and rabbanim.

He purchased an estate in idyllic Monsey, far from the distractions and noise of the city, for this purpose. The staff he selected reflected his own breadth, his vision for the talmidim of this high-level institution. Rav Reuven Grozovsky, son in law and confidante of Rav Baruch Ber of Kamenitz, delivered the main shiur. Rav Yisrael Chaim Kaplan, son-in-law of Rav Yerucham Levovitz, delivered shiur and also served as mashgiach. This tapestry was woven together with the rich threads of Torah Vodaath’s most accomplished alumnus: Rav Gedalia Schorr, talmid of Rav Aharon Kotler’s Kletzk, chassid of Sadiger, and disciple of the chassidic schools of the Sfas Emes’s Ger and Reb Tzadok’s Lublin, served as menahel and gave the yeshivah its spirit.

Each individual talmid, about 40 in all, the choicest young men of the American yeshivah world, found a well from which to drink between the towering maple trees. The talmidim of Beth Medrash Elyon were as much a story as their rebbeim: boys from the streets of Brownsville or the Lower East Side who could rival their prewar counterparts.

At the Monsey dining room table of Reb Yeshaya Dovid Waxman, I hear a recollection. “My roommate was Rav Moshe Green. Today he’s a big rosh yeshivah, but then he was a just a boy from East New York. He liked to learn late, and when he came into the room, the others were often sleeping. He wanted to recite a lengthy Krias Shema, but he would never have done it on the cheshbon of others, so he would go back out into the hall and say his Shema, the way he wanted to.

“The middos in that yeshivah were like in Kelm.”

It wasn’t just the bochurim; the elevated atmosphere affected the employees as well; perhaps it was even spawned by them. There were the Apfledorfers, the couple who cooked for the bochurim. Of them, Rav Yaakov Kamenetsky said that it would we be worth it to attend the yeshivah simply to witness their chesed. After losing his spouse and children in the war, Reb Leib Apfeldorfer remarried a fellow survivor: they had no children of their own, but together, they decided that the talmidim at the yeshivah would be their offspring. There was Johnson, the deaf custodian who did his work with dignity and pride, perceiving, on some level, just how lofty a calling it was. There is a humorous tale they tell, the old-timers, about the mashgiach, Reb Yisrael Chaim, who, totally immersed in his spiritual pursuits, never really understood America.

The Mashgiach noticed a huddle of bochurim in conversation, and he approached, wondering what they were discussing with such emotion. “Kennedy was shot,” one of the talmidim said, filling him in.

The Mashgiach digested the information. “And who is president now?” he asked.

“Johnson has succeed him,” the bochur explained.

“Johnson!” exclaimed the holy Mashgiach, certain they were referring to the only one he knew with that name. “Why, I saw him not ten minutes ago. Amazing!”

LIFE ITSELF

Shabbos in yeshivah was the climax of the week. The bochurim would sing, and then, after the seudah, they would hurry back to the beis medrash. No one perused the weekly sedrah; Leil Shabbos was an intense learning seder, preparing for the shiur to be held the next day.

There were no waiters: the bochurim filled that role willingly.

At each seudah, someone would ask a kushya to his tablemates, the conversation at least as essential as the nutrients. Sometimes there was a satisfactory answer, other times there wasn’t: It made no difference. It wasn’t about answers but life itself.

The hasmadah reflected the urgency of that call. Rav Tzvi Elimelech Waxman, today a rav and rosh kollel in Monsey, but back then the executive director of the kollel, recalls just how serious each moment was. “No one had any money, but the yungeleit, who knew how hard we worked to meet payroll, would sometimes donate back some of their meager paychecks to the kollel. There was a gaon in yeshivah, Reb Leizer Lauer, who would give me $3.42, or $4.78, always a random number. I once asked him about this strange minhag; if it was maaser, why not give a proper round number? He explained that this wasn’t maaser; rather, he’d figured out the ratio of hours to dollars each month. Then, he deducted the proportionate amount for each minute he’d wasted, if he’d stepped out of the beis medrash.”

About the job itself, Reb Hershel, as he’s known, shares a tidbit. He was on his way to a career in chinuch when, discerning his organizational abilities and resourcefulness, the roshei yeshivah asked him to join the administration of the kollel.

“But I didn’t want to be a fund-raiser, and I let them know it. So Reb Reuven showed me a gemara about the value of talmud Torah of the rabbim, the public benefit, and he told me, ‘You will have the zechus of supporting yungeleit who will each have their own yeshivos one day.” (Rav Simcha Schustal, Rav Don Ungarisher, Rav Moshe Dovid Steinwurzel, Rav Mottel Weinberg, and Rav Yaakov Moshe Kulefsky, among others, would occupy places of distinction on the eastern wall of the American Torah world.) There were the Yamim Noraim in Beth Medrash Elyon, the sublime tefillos of Reb Hershel Mashinsky and Rav Simcha Schustal, the transcendent tekias shofar of Rav Yaakov Moshe Kulefsky. A half century later, their sounds are still seared onto the souls of those privileged to have been there.

WE NEED OUR LIONS

The story is told that when Rav Yitzchok Hutner assumed the leadership of Yeshivas Rabbeinu Chaim Berlin, Rav Shraga Feivel sent him a group of capable young scholars, the nucleus upon which Rav Hutner’s yeshivah would flourish. The board of directors at Torah Vodaath was upset, but Reb Shraga Feivel insisted he had acted correctly. “I don’t work for Torah Vodaath, but for Hashem. He made me a menahel and I need to do what’s best for Him.”

“Okay then,” one of the balabatim challenged Reb Shraga Feivel, “why not send Ungarisher and Schustal there as well?”

Reb Shraga Feivel smiled. “Because our yeshivah isn’t less deserving than any of the others; we also need our lions.” Don Ungarisher and Simcha Schustal — according to many, the two catalysts for Reb Shraga Feivel’s creation of the elite yeshivah in Monsey — were not alone, there were many others. There was a small chaburah of yungeleit that would have illuminated the world, had they only lived, people like Rav Moshe Dovid Steinwurzel, Rav Leizer Lauer, Rav Hirsch Goldwurm….

And even in that select group, Reb Shmelka stood tall….

AN ILUY HAS ARRIVED

Shmelke Taubenfeld arrived in America in 1949, seemingly a finished product, proficient in Shas, poskim, and Midrash. But when had he had time to learn? He’d attended cheder in his native Yaroslav, but by the time he reached his teens in the early 1940s, he was on the run from the Nazis, eventually ending up in freezing Siberia, a place barren of life, certainly of seforim.

In later years, Reb Shmelke once related how his childhood melamed would come to him each Siberian night in a dream and learn with him. One freezing night, he grasped how strange it was — a melamed who’d already passed away coming to teach him — and after that, the melamed stopped coming.

Miraculous means or not, there was nothing ordinary about the young man’s knowledge.

After Siberia and the war, he ended up in Germany for a brief period, where the only seforim were a set of Shas, a Shulchan Aruch consisting of the Mechaber and Rema, and one chelek of Yoreh Dei’ah with all the commentaries. Later on, when he would reach the age of shidduchim, his mother would ask what she could tell shadchanim about him.

Out of respect, he told her the truth; Shas, Shulchan Aruch with Rema, and Yoreh Dei’ah with all the meforshim.

He traveled to Eretz Yisrael, for a single year in the late 1940s where he joined the nascent Belzer yeshivah in Yerushalayim. The Rebbe Reb Ahre’le, lived in Tel Aviv, and made it clear that the bochurim were to remain at the yeshivah, rather than join him for Shabbos, except for one. The young man from Yaroslav was welcome.

From there, the bochur traveled to America.

After spending a few weeks in Torah Vodaath, he set his sights on the elite yeshivah in Monsey. The rosh yeshivah, Rav Reuven, was wary of the Galician newcomer, who didn’t seem like a good fit with the Lithuanian-style yeshivah. In addition, the policy was that Beth Medrash Elyon was only for talmidim who’d completed two years at Torah Vodaath.

Nevertheless, a bechinah was arranged. The bochur sat in on the Rosh Yeshivah’s shiur, and afterward, he reviewed it for Reb Reuven, word for word, not missing a single nuance. Reb Shmelka’s repetition of the shiur was impeccable. “At this point, the Rosh Yeshivah paused to cough,” the bochur told the Rosh Yeshivah. “Today,” the Rosh Yeshivah remarked to the other rebbeim, “an eme’se iluy arrived.”

Reb Shmelka would become a prize talmid. In time, the Belzer chassid and his Minsk-born rebbi would connect in another realm as well. Reb Shmelka spent the Seder night at his rebbi’s table, and would later relate how enthralled he was by Reb Reuven’s recitation of Nishmas Kol Chai.

HE NEEDS A SHTENDER

Within weeks, Reb Shmelka had entrenched himself in the beis medrash. He seemed to learn day and night, sleeping only when he felt it absolutely necessary. With visible nostalgia, Rabbi Nosson Scherman, general editor of Artscroll/Mesorah, remembers his roommate of those years.

“One morning, Shmelka missed breakfast and Johnson made sure to save a portion for him. Another bochur also overslept, but didn’t receive the same service from the kindly custodian. He complained, but Johnson didn’t apologize. ‘He was in the study hall all night, you were sleeping.’ ”

And this from the personable caretaker. One of the bochurim commissioned Johnson to construct a wooden shtender for him. “You?” wondered Johnson, “You don’t need a new shtender, Red (his nick-name for the red-bearded Reb Shmelka) he needs a new shtender, he uses his up, you don’t.”

Rabbi Scherman recalls how when the yeshivah got a copy of the sefer Yam Shel Shlomo on masechta Chullin. Rabbi Scherman walks to the book-lined shelves of his office at Artscroll/Mesorah headquarters and mimics Reb Shmelka’s stance near the yeshivah’s seforim shelf, one foot crossed over the other, brow furrowed in intensity. “He learned through the entire sefer in one morning. We told Rav Schorr, but he didn’t believe it, so he went to farher Reb Shmelka on the sefer. He was astounded.”

Virtually every sefer in Beth Medrash Elyon seemed to have loose red hairs between its pages, mementos of their most loyal friend.

Someone quoted a Zohar in front of Reb Shmelka. “It’s not in Bereishis, Shemos, Vayikra or Devarim,” he responded, “perhaps it’s in Bamidbar.”

Reb Eli Tabak, a member of Reb Shmelka’s close-knit chaburah, recalls the night Reb Shmelka first discovered a sefer written by Ramchal, called Yarim Moshe. “He learned through the entire sefer that first night, and he said over from it for the rest of his life.”

Reb Shmelka was repeating a gemara in masechta Zevachim, and he misquoted a word. His pain at discovering his mistake was intense: The next day, his friends saw him relearning the entire masechta.

When he later became a rav, he was once delivering a shiur on Ohr Hachayim Hakadosh on a Friday night when the lights suddenly went out. Undaunted, Reb Shmelka continued, word for word.

Rabbi Waxman shares a story about how Reb Shmelka once filled in as a substitute daf yomi maggid shiur at Monsey’s Beis Yisroel shul. “A gentleman, Mr. Harris, approached to ask a question after the shiur was over, but he wanted to look in the gemara to read the words properly. He was standing next to Reb Shmelka, so he reached for Reb Shmelka’s gemara: Reb Shmelka stopped him. ‘There’s no need, just ask the question.’ He seemed agitated.

“Unable to ask without seeing the words of the gemara, Mr. Harris opened the gemara to the correct place — and saw that Reb Shmelka’s gemara was missing the daf upon which he’d just expounded.

“To read a blatt gemara by heart,” reflects Rabbi Waxman, “is impressive, but doable. But to give a shiur, stopping and starting, engaging in back-and-forth and answering questions, and then returning to the text without a page, is superhuman.”

A visitor from another institution visited old-school Beth Medrash Elyon, eager to expose the faults of the traditional system, which doesn’t put great emphasis on learning Tanach, and even less on the “seven wisdoms.” The academic started up with the first talmid he saw in the beis medrash: if ever someone picked the wrong man, it was he. Reb Shmelka’s proficiency in dikduk, history, mathematics, and astronomy, all culled from the words of Tanach, Chazal, and Medrash, left the guest incredulous.

Reb Shmelka seemed to know it all: he was an expert in nusach, an aficionado in the tunes and melodic tenuos used in different chassidic courts, and had a vast array of stories which he used to great effect. Any area upon which he expounded, it seemed, was “his” expertise.

NOT THE ACTION, BUT THE REACTION

His brilliance was matched only by his humility.

There was a fellow in yeshivah who mistook Reb Shmelka’s natural modesty for acknowledgement and he would argue with Reb Shmelka in learning, convinced by Reb Shmelka’s silence that he was in the right. “You are speaking like a silly person,” he once remarked to Reb Shmelka, who sat quietly and didn’t respond. “This is a silly sevara,” he said another time. Though Reb Shmelka didn’t react, the talmidim around him were bristling at the slight to their hero, the towering figure of the yeshivah.

“That answer is silly,” was the comment a third time, to the growing frustration of the other yungeleit.

One morning, this talmid suggested a solution to a question posed by Reb Shmelka. Reb Shmelka calmly pointed out that the answer was inconsistent with an open gemara. “Now who’s silly?” Reb Shmelka smiled.

Unable to contain themselves, the surrounding talmidim stood up and applauded good-naturedly.

Brilliance, humility, and incredible grace, Rabbi Scherman recalls.

The talmidim hosted a sheva brachos for one of their friends, and invited one of the leading rabbanim in Monsey to speak. The rav didn’t show up, and so Reb Shmelka rose to give an impromptu derashah. In the middle of Reb Shmelka’s compelling derashah, the guest rav suddenly appeared: Reb Shmelka seamlessly stopped and sat down in mid-sentence, lest the visitor feel badly at having been replaced.

“It’s not the action as much as the fact that it was a reaction,” Rabbi Scherman remarks, “it takes years of work to be able to do that instinctively.”

When asked to deliver a shiur at a yeshivah, Reb Shmelka demurred. “It’s one thing to speak in learning with balabatim who work all day, so I don’t feel like I’m wasting their time, but what gives me the right to take away time for bochurim who learn all day?”

THE ROITTE GAON

Reb Shmelka married the daughter of Reb Yosef Dov Segal; an eishes chaver ready and willing to facilitate the life he wished to live. (Her sisters also married prominent rabbanim: Rav Shmuel Alexander Unsdorfer and Rav Avrohom Chaim Spitzer). They settled in one of the tiny kollel bungalows on the yeshivah campus and he continued to soar. Slowly, residents of the growing Monsey community began to realize the stature of the frail, thoughtful scholar with the red beard.

When they visited the gedolim of Eretz Yisrael, they noticed how the name “Monsey” suddenly registered. The Tchebiner Rav would always send regards to the “roite gaon” and the Brisker Rav was known to appreciate him: Years earlier, the Rav, not known for engaging in lengthy conversation, had hosted Reb Shmelka for close to an hour and spoke with him in learning. From them on, he had a deep respect for the Monsey resident.

A charming bit of hometown history. In its early years, The Jewish Press featured a weekly Torah trivia question, the answer usually an obscure medrash or source in Chazal. More often than not, the winner came from Monsey, New York. This was a demographic anomaly, considering that there were more readers on some Brooklyn blocks than in all of Monsey.

But Monsey had Reb Shmelka, so the children would hurry into the shul, and breathlessly ask: “What was the name of Manoach’s wife?” or some such question, and always, they received an answer on the spot.

The face of Rav Dovid Schustal, rosh yeshivah of Lakewood’s Beth Medrash Govoha — who grew up in that glorious time and place — lights up at the mention of Reb Shmelka’s name. “He was derhoibben, he was elevated, and he lifted everyone up around him too, the whole chaburah.”

A SINGLE TEFILLAH

In time, a devoted chaburah gathered around Reb Shmelka; they established a small shul of their own, these balabatim who clung to him as a chassid to a rebbe. He himself didn’t respond to the title ‘rav,’ preferring to see himself as a rosh chaburah, and he wouldn’t accept a formal salary from the shul. He established the minyan with a single tefillah. “The Ribbono shel Olam should help that if, for any reason, He doesn’t have satisfaction from our efforts, then ess zohl unter gein, the endeavor should fail.” Until today, the shul — Beis Medrash Charedim — remains vibrant under the leadership of Reb Shmelka’s son, Reb Yosef; along with its Torah-soaked walls, it has maintained its unpretentiousness.

Three decades after his passing, his people still exude pride at the gift they were given, the privilege they enjoyed. Speaking with them, you get the sense that they consider the entire story — the person, his knowledge, his lofty levels, his radiance — to have been a secret: their secret.

Hardly a day goes by that they don’t repeat over some thought, vort, or story from him, their rebbe.

Reb Zundel Klein walks along Remsen Avenue and reminisces about the nightly Gemara shiur, a small group of working men drinking from the deepest wells. Wasn’t it hard for them?

“Yes,” he laughs, “but we prepared well.”

Once, someone complained that the shiur was simply too complex for balabatim. The next evening, Reb Shmelka spoke slowly, enunciating each word and not delving past the simplest pshat in the gemara, toiling to keep the floodgates shut. It lasted for one night. The next evening he was back in full form, challenging his listeners with each word.

Reb Shmelka’s people revered him, and he respected them greatly.

Reb Yankel Feldheim, a businessman, served as head of the small kehillah, dedicated to the Rav and his needs. Once, he drove Reb Shmelka somewhere and tried to help the Rav with his suitcase.

“I should make use of a talmid chacham?” Reb Shmelka wondered, refusing to allow the layman to assist him.

Reb Yankel looked at his rebbi in surprise.

“Reb Yankel, whatever bad middos I have, I was never choneif another person, I am not a flatterer; I cannot allow you to serve me.”

When one of his people was blessed with a son, Reb Shmelka was there, at their home, the night before the bris. The minhag of the traditional vach nacht is for the father to remain awake, learning through the night near the new infant. Knowing that it was difficult for most people to push through, the Rav would spend the night immersed in learning, happy to allow the new father some rest.

A member of the chaburah had a baby boy. He wasn’t feeling well the night before his son’s bris, and the new mother had the burden of serving the traditional vach nacht seudah on her own. Exhausted as the many guests filed out, she longed for nothing more than a soft bed. She noticed Reb Shmelka in his coat, on the way out, and she headed off to sleep. She slumbered blissfully throughout the night, and near dawn, she awoke with a start. She’d left the baby sleeping in carriage in the living room, but she hadn’t heard him all night; why hadn’t he woke her? Had he cried himself hoarse as she slept?

She came out and saw Reb Shmelka deep in learning, happily rocking the child back and forth, as he’d been doing throughout the long night.

One of Reb Shmelka’s people was redoing his roof when unexpected raindrops began to fall, jeopardizing the job and potentially causing extensive damage. Without hesitating, he ran to Reb Shmelka, who laughingly told him not to worry before sending him back outside, where the sun shone brightly: less a story about Reb Shmelka’s supernatural abilities than the complete confidence his people had in him.

His devoted rebbetzin accommodated his intolerance for luxuries, and there was no air-conditioning in their small home. One of his chavrusas endured a medical procedure, and as a result, he felt that he needed air-conditioning in order to be able to concentrate properly: The next day, an air-conditioner hummed in the window.

WHAT THE REBBE MEANT

He was a slight man, lack of sleep evident on his face. His beard was a reddish gray, much of it pulled out as he learned. Awe-inspiring a figure as he was, his relationship with the mispallelim at Charedim was paternal. When he spoke at the weekly Seudah Shlishis, he tended to travel in higher worlds, losing his grip on time. His people listened valiantly, but when his words or ideas were out of reach one of them would rise and bring in mayim acharonim. He would smile and they would bentsh.

More often that not, discussions would break out after Shabbos davening and he would get involved in conversation with one of his people. Complex and intricate as the conversation would be, Reb Shmelka understood that a child eager to go home and eat might not appreciate his fathers’ post-davening Torah discussion; the Rav would hold the hands of the child between his own, gently stroking them the entire time he spoke with the father. Reb Shmelka had the ability to relate to all of them, to simplify the most esoteric ideas in a way that could warm their souls as well. Someone once quoted a “joke” of the famously witty Ropshitzer Rebbe, who used humor to share penetrating messages. “The tefillah of Ein K’Elokeinu is so beautiful,” the Rebbe remarked, “why then do we save it for the end of davening rather than say it right away?” The Rebbe answered his question. “Because if we did that, someone might come in by Ein K’Elokeinu and assume that he’s already missed davening.”

Reb Shmelka explained the depth of the witticism. “Tefillah is a process, an ascending order through the worlds from atzilus, to bri’ah, then yetzirah, and finally the world of asiyah. But in the tefillah of Ein K’Elokeinu itself, there are four parts that correspond to the four spheres: that is what the Ropshitzer meant that one might consider the tefillah to be the entire davening.”

His dry Galician wit was evident in the advice he gave. A talmid chacham asked his opinion about accepting a position in a prominent institution with a celebrated staff. Perceiving that it wouldn’t be an easy place to work, Reb Shmelka smiled. “Listen,” he said, “if you fail over there, you’ll be out in six months… and if you succeed? You’ll be out in three months!”

Reb Shmelka learned masechta Berachos with a chavrusa, and they reached the gemara that tells how the ascetic Rabi Chanina ben Dosa was the medium for the sustenance for all of creation. When encountering the words of Chazal that “the entire world exists in merit of my son Chanina, and Chanina survives on a measure of carobs from Erev Shabbos to Erev Shabbos,” his chavrusa took it to mean that Rabi Chanina ben Dosa ate only one meal a week. “Did Rabi Chanina ben Dosa not make Kiddush on Shabbos?” he wondered.

Reb Shmelka looked at him and then closed his gemara and left the room. His ears wouldn’t tolerate the words, the casual way the chavrusa had made the suggestion.

The next day, he returned with a list of proofs that the words “from Erev Shabbos until Erev Shabbos” don’t include Shabbos itself. At the pidyon haben for one of his mispallelim, he discussed the teaching of kadmonim that one who partakes in the seudah of a pidyon haben, it’s as if he fasted 84 taaneisim. Reb Shmelka explained this to mean that he atones for all the misdeeds about which Chazal say “as if’,” to underscore the severity of the sin. (For example: One who gets angry, it’s as if he worshipped avodah zarah.) Then, Reb Shmelka proceeded to enumerate the instances that the term “as if” describe a sin — 84 times!

EVEN THEIR CHILDREN

Beis Medrash Charedim, as his shul was known, wasn’t a large shul — but it was a potent shul. His people carried themselves a bit straighter, uplifted through him — even their children feeling pride at their association with him.

Succos was a special time. He would begin work on his succah during the day upon which we recite, in Selichos, the words “Yachbienu b’tzel yado tachas kanfei haShechina.” He would personally perform each and every rite associated with the mitzvah, from picking sechach, to building the structure, and then laying the sechach himself.

But never, in his zeal, did he lose sight of the bigger picture. Each year, he would go pick sechach along with someone close to him, a father of a family blessed with several energetic boys. The children reveled in the adventure of cutting the stalks and loading up the car for a precarious trip back to Monsey.

One year, Reb Shmelka decided to switch to bamboo sechach — after decades of fiercely protecting the minhag of using leafy sechach. He explained that he sensed that the family that accompanied him each year was losing their enthusiasm: the boys had grown older and no longer considered picking sechach as enjoyable as they once had. Reb Shmelka felt that they were simply going out of respect for him, and he wouldn’t perform a mitzvah when there was a trace of lo sirdeh lo b’forech, making another Jew toil for his benefit. And so he was yotzei with bamboo.

TOO PUBLIC

The first night of Rosh Hashanah 5746, 1985, Monsey Boulevard was dark with people, throngs lining up to wish a gut yahr to the giant who led the humble chaburah at Charedim. One of Reb Shmelka’s close talmidim recalls the sense of discomfort that filled him when he saw the crowds. “It didn’t feel right, exposure just didn’t fit with Reb Shmelka.”

Two weeks later, on Erev Succos, Reb Shmelka sat with one of the children of the kehillah, testing him on his learning. He delivered a shiur on hilchos Succah. He’d never been a strong man, and suffered from various ailments ever since he’d been a teenager in freezing Siberia, but he felt even weaker than usual. He laid the sechach atop his succah himself, but he was unable to complete the beloved task.

He came to shul for Maariv, but asked the gabbai to announce that he was too weak to receive the traditional Yom Tov visitors that night following the seudah. But there were those who didn’t get the message and they came: so Reb Shmelka received them graciously and sat with them, speaking in learning.

That night, Reb Yeshaya Dovid Waxman had a strange dream. He saw a crowd filling up Yerushalayim’s Zichron Moshe shul and fervently saying Tehillim, tears flowing down their cheeks.

Early in the morning, he awoke in fright and hurried off to his regular early morning learning session with Reb Shmelka.

For the first time in years, Reb Shmelka wasn’t there.

The Rav had sustained a major heart attack. At noon on the first day of Yom Tov, the Ribbono shel Olam took for Himself a perfect esrog, the pure soul of Reb Shmuel Shmelka Taubenfeld.

The levayah was held that evening, Leil Yom Tov Sheini, the melachos done by b’nei Eretz Yisrael in accordance with a psak that the niftar had given one of his own talmidim. It was a quick levayah, unceremonious as the soul from which they were parting.

The niftar was taken to Eretz Yisrael, laid to rest near his great rebbi, Reb Ahre’le of Belz, on Har Hamenuchos.

THE FEW, THE PROUD

There was a vort that Reb Shmelka loved.

The gemara in Taanis (26) says that there were no Yamim Tovim as joyous as the 15th of Av. One of its special features was its status as “the day of the breaking of the ax.” On that day, the annual cutting of firewood, the atzei hama’arachah, was completed. Wood with worms in it could not be used on the Mizbeiach; during the spring and early summer months, the sun’s blazing heat would kill the worms, but after mid-Av, this was no longer the case, so they would stop cutting. The conclusion of this mitzvah was celebrated with great joy.

The reason for the distinctiveness of this Yom Tov is that there would be more time to learn Torah, as the gemara continues. Asked Reb Shmelka: How many people were involved in the cutting of wood for the Beis Hamikdash? Ten? Fifteen? Even if it was more than that, why did the whole Klal Yisrael merit a Yom Tov because a small group of people had more time to learn?

Reb Shmelka would conclude that it appears that at a few more minutes in the beis medrash, for a few more Yidden, is a national celebration.

A few more Yidden … like that group in Beth Medrash Elyon, a few hearty young men ready to turn their backs on America and restore the splendor that had been lost, buried in Mir and Baranovitch, in Warsaw and Pressburg. What they lacked in numbers they made up for in determination, focus, and vision, a small army with big dreams.

Woodcutters for a nation, toiling to reignite a fire extinguished, so that it might roar once more.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 530)

Oops! We could not locate your form.