Modeh Ani

| November 30, 2021Hakaras hatov means thanks, but it starts with hakarah, recognizing that someone, or Someone, did something good for you

As told by Rabbi Shmuel Goldstein to Meir Schiller

"Yesh lachem hashgachah mil’malah — Someone Above is taking care of you”

Seven years ago, Rav Aharon Taussig shlita came to Har Nof to speak at a shloshim in Elul.

“Why do we say Shehecheyanu on Yom Kippur night?” he asked. “The brachah is usually recited only when performing a seasonal mitzvah.”

I’ll never forget his answer, and the new meaning it would take on just a few months later: that as we approach Yom haDin, it is appropriate to give Hashem heartfelt thanks for keeping us alive from year to year. The essence of Yom Kippur, in fact, is seasonal.

I’m young – only 42, a father of young children, baruch Hashem, I thought. I have many Yom Kippurs ahead of me to thank Hashem for life.

But just a few months later, Hashem taught me not to take things for granted, that life is only as long as He decrees.

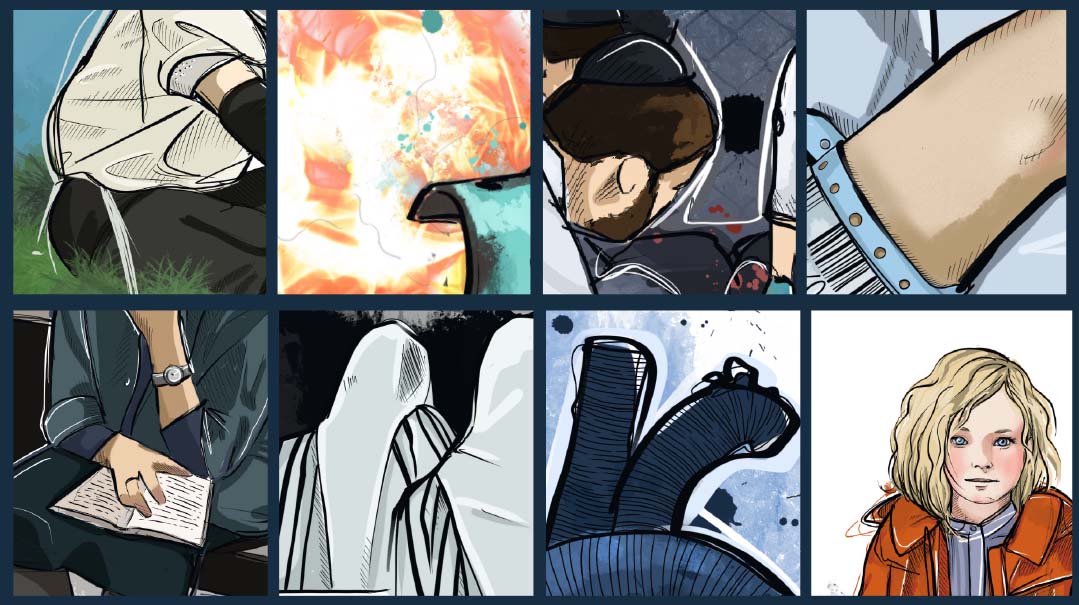

At 6:55 a.m. on November 18, 2014 — 25 Cheshvan 5775 — I was davening Shacharis in Kehillas Bnei Torah, Rabbi Rubin’s shul. The shul is down the block from my apartment on Rechov Agassi in Har Nof, and I’ve davened there almost every day for years. My 12-year-old-son was with me that morning, and just before seven a.m., we were standing for Shemoneh Esrei. I was up to the last brachah, Sim Shalom, ironically, when suddenly, we heard gunshots. They sounded close by.

“Pigua!” someone shouted, and we all dropped to the floor.

Two terrorists were in the hallway. One of them shot the person standing there before they burst into the shul itself.

“Itbah al yahud — slaughter the Jews! Allah akbar — G-d is great!” they yelled — and then it was absolute carnage.

Gunshots rang out as bullets slammed into walls; the terrorists were determined to take down my davening mates, my friends, our minyan 30-strong. Shtenders were thrown back and forth, and a huge table came flying through the air as mispallelim tried to fight off the satanic devils.

Suddenly, there was silence — you could hear a pin drop. Apparently, miraculously, one of the terrorists’ guns jammed. The other terrorist began hitting people with a meat cleaver.

Meanwhile, my son lay at my side, tightly grasping my hand. He sensed someone was crawling out, and baruch Hashem, in an uncharacteristically independent manner, let go of me to follow that person. He managed to crawl out an exit, after which he ran straight home.

And then it happened: The terrorist reached me and bashed me repeatedly with the meat cleaver, on my head, neck, and lower back, before leaving me for dead on the floor. I looked up and noticed his back was toward me, while the other terrorist was still distracted, fumbling with his jammed gun.

I felt a surge of adrenaline — that koach came straight from Hashem — and in an effort to spare the lives of the remaining mispallelim, I jumped him from the back, wrestling him down. He dropped his cleaver, and then, to my surprise, a gun fell from his pocket to the floor. Before I could even think of my next move, the other terrorist, who saw his comrade had fallen, ran over to help. Inexplicably, all he said to me, in his Arabic accent, was “Lech mipoh — leave, go away from here!”

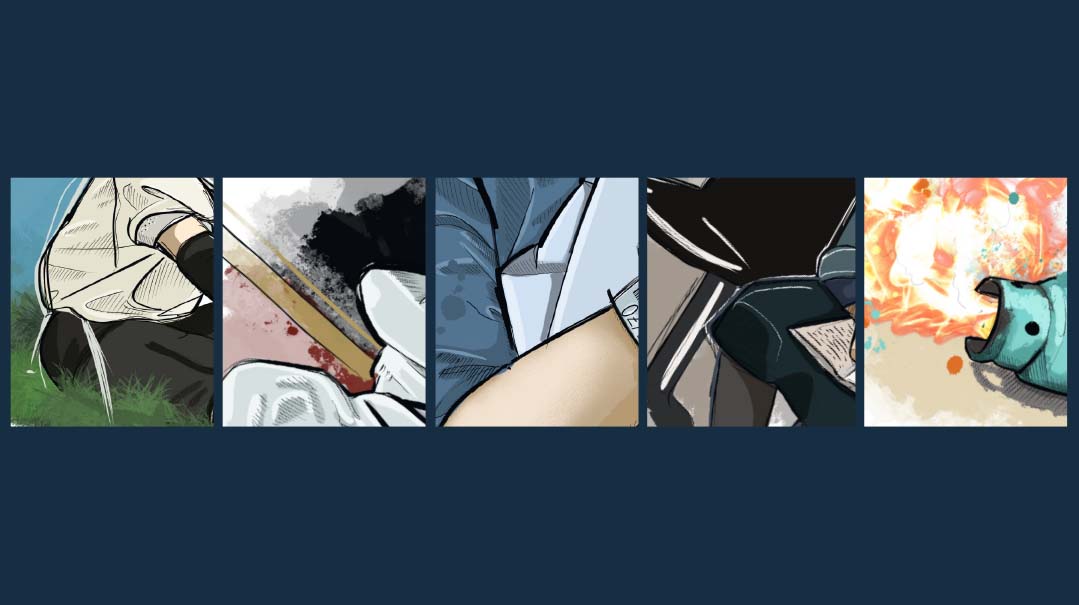

I didn’t wait to be asked twice; I hobbled out of the shul, shuffling down the stairs. I was critically wounded, bleeding profusely as I made my way out of the building, and I felt terrible for leaving everyone else inside.

I bumped into a young man, who gave me the shirt off his back, literally, using it to bandage my head.

“I know only two things about medicine,” he later explained. “Take an aspirin and put pressure on a bleeding wound.”

With that knowledge, he saved my life.

I sat to rest on a rock, and I saw a Hatzolah member rushing to the entrance of the shul, desperate to help the mispallelim inside.

“Don’t go in,” I warned him. “They’re shooting in there!” He went anyway, met with flying bullets, and stumbled back out. His partner was right behind him and so intent on helping that the first Hatzolah member literally pushed him down the stairs to prevent him from entering; he broke his ankle, but was spared a fatal bullet.

Dr. Joyce Morel, a Canadian emergency medicine physician who had recently made aliyah and was working as a physician in Israel, had answered the call for volunteer first responders ringing through Har Nof. She saw me bleeding profusely — the knife wound to my back had exposed several ribs and one of my lungs — and she began treating me.

It was still an active attack, so Dr. Morel and two others rushed me onto an ambulance.

“My son, where’s my son?” I pleaded.

Only once I was told he had made it home did I allow the ambulance to drive away. Dr. Morel treated me until we arrived at Hadassah Ein Kerem, where I went straight into 11 hours of multiple surgeries. The doctors worked furiously to save me, but they had no real hope — and they said as much to my wife, Miri.

“Come to the hospital, and bring someone along for emotional support,” Miri remembers being told. “There is a zero-percent chance your husband will make it.”

Hours later, though, the doctors emerged, victorious.

“Yesh lachem hashgachah mil’malah — Someone Above is taking care of you,” they said in awe.

The doctor who successfully reattached my ear — the terrorist had sliced it, and it hung by a thin piece of skin — later told me, “I attached it thinking there is a slim chance I’d be able to.” He then added emotionally, “But we believe in nissim, so I tried.”

From that point on, he started wearing a yarmulke.

Because of my medical situation, it took a few days until I heard the tragic news: that four of my friends — Rabbi Moshe Twersky Hy”d, Rabbi Kalman Zev Levine Hy”d, Rabbi Aryeh Kupinsky Hy”d, and Rabbi Avraham Shmuel Goldberg Hy”d — were brutally murdered on that day, and a fifth, Rabbi Chaim Rotman, was in a coma. (He hung on for a year before joining the other kedoshim.) Five others were also injured, some seriously.

Recovery took me some time, but baruch Hashem, I was alive. One of the people that came to visit when I was recuperating told me he, too, had experienced an open neis — he was pulled out of a totaled car — and he asked his rav how he could hold onto that immense feeling of gratitude to Hashem always, that it shouldn’t fade with time. I don’t recall what his rav said, but I have my own answer: Say Modeh Ani, Modim in Shemoneh Esrei, Nodeh Lecha in bentshing, all of the tefillos that thank Hashem for sustaining life, with full concentration. If you always do that, even as the memories fade, your gratitude won’t.

In Pachad Yitzchok Chanukah, Rav Yitzchok Hutner ztz”l explains that gratitude in Hebrew, “hoda’ah,” is a three-in-one word — modeh, hodah, todah — and only after the first two are you ready for the third. After being modeh al ha’emes, acknowledging the truth, that there are many so-called “natural” nissim daily, then you experience hoda’as Baal Din, gratitude for the nissim Hashem does for you, and only then can you say todah Hashem for nissim every day, not just when terrorists strike. Similarly, hakaras hatov means thanks, but it starts with hakarah, recognizing that someone, or Someone, did something good for you.

Every year, on the Shabbos closest to 25 Cheshvan, my family and friends form a minyan in our house, and I make a seudas hoda’ah to thank Hashem for sparing me. Either I or someone in the family makes a siyum. I also share the story of my neis with my chaburah in the Mir so my talmidim can partake in the hoda’ah, and I give out a few copies of my kuntrus, Ashira L’Hashem, which I wrote after the massacre to strengthen emunah. I called my sefer Ashira L’Hashem because when I came to after my surgeries, the first words I said were, “Ashira lashem bechayay — I will sing praise to Hashem as long as I live.”

At the first seudas hoda’ah, my family asked, “What do we say to you? You say mazel tov to the baal simchah at a chasunah or bar mitzvah, but this is neither.”

“You can say mazel tov to me, too,” I responded. “I am indeed a baal simchah, someone who is happy about all Hashem did for me. I am still alive and standing, and that is the purpose of this seudah: to sing praise to Hashem, to thank Hashem.”

For me, the memories of that morning are about the pain as well as the gratitude. I think of the Chayei Adam at the end of the sefer, where he describes a major fire in his courtyard. The fire claimed the lives of 31 of his neighbors, but because his entire family was saved, they made a seudah every year on 16 Kislev, the anniversary of the fire. This seudah, the Chayei Adam explains, celebrated their own survival even as he and his family still mourned the tragic loss of life.

I, too, have mixed emotions. Indeed, I am a baal simchah, yet I am a baal simchah who remembers five dear friends, five entire worlds, holy worlds, mercilessly cut down.

But I also think about the fact that the terrorists had been hoping to destroy all of us at that minyan — and more, as the mispallelim of the 7:00 a.m. minyan were on their way into the building to daven upstairs, but when they saw me bleeding outside, they quickly turned back.

Five souls taken. So many spared.

Chanukah is a time to thank Hashem for all He does for us, especially for the miracles that light up the darkest of times. We aren’t, chas v’shalom, overlooking the losses suffered in those dark times, rather we are appreciating Hashem’s love, which we see overtly in the miracles.

“B’rega katon azavtich, u’verachamim gedolim akabtzeich. B’shetzef ketzef histarti panai rega mimeich, uv’chesed olam richamtich,” the Navi Yeshaya tells us. The maelstrom of the moments Hashem’s wrath is upon us are followed by times of great mercy and chesed. Modeh ani.

Rabbi Shmuel Goldstein is a rosh chaburah in the Mir in Jerusalem.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 888)

Oops! We could not locate your form.