Who was Reb Shaya Blau a”h, and how did he save so many from the Churban in Europe?

T

he kiddush on Shabbos morning in the Bobov shul in New York was already underway when the two guests, an older man and his son, entered and quietly took seats in the back.

The Rebbe, Rav Shloime Halberstam ztz”l, presided over the gathering of chassidim, who were Holocaust survivors like himself. Suddenly the Rebbe took note of the late arrivals.

“Shalom aleichem!” said the Rebbe heartily, rising from his seat to honor the guests, to the amazement of everyone. The chassidim glanced around and wondered why the Rebbe was according such respect to this clean-shaven older gentleman.

“Do you know who this is?” the Rebbe asked the chassidim. “This is Reb Shaya Blau. He saved hundreds, maybe thousands of Yidden from the Nazi inferno. Ich bin mekaneh zein Gan Eden — I envy his share in Gan Eden!”

Who was Reb Shaya Blau a”h, and how did he save so many from the Churban in Europe? His son, Reb Lazer — who accompanied his father to that kiddush in the Bobov shul — recounts the tale.

Reb Shaya actually got his first test of bravery not in World War II, but in World War I, as a soldier in the Austro-Hungarian army. Through the hardships of military service, he kept a warm connection to Yiddishkeit by learning from a Kitzur Shulchan Aruch he carried with him at all times.

Once, he came under enemy fire in a battle, and fell to the ground. When the smoke cleared, he saw that he had been hit — but only in the thumb, from which he was bleeding profusely. He lifted himself up, wrapped his thumb in a cloth to stop the bleeding, and decided to end his army career.

It took him two days to make it to his parents’ house, and upon arriving, he found a package addressed to them. Wondering what it was, he opened it to find his Kitzur Shulchan Aruch. Inside the sefer, the Jew who had sent it inscribed, “This is the sefer of your son Shaya. I witnessed him being shot to death.” This Jew had seen Reb Shaya fall, but by the time he was able to make his way over to him, Shaya was gone, leaving behind only the sefer.

As Reb Shaya read and reread those words, he felt overwhelmed with gratitude to HaKadosh Baruch Hu. He kept that sefer as a precious memento his whole life, and bequeathed it to his son Lazer after his passing. (The family first heard this story at the shivah.)

“It’s really the story of my father’s life,” Reb Lazer says. “It was miracle after miracle.”

Although miracles played a part, Reb Shaya wrote a large part of the story with his grit, tenacity, and ingenuity. When, during World War II, Hungary came under the rule of the fascist Arrow Cross party, and the Jews were made to don yellow stars, Reb Shaya Blau refused. With his fluent Hungarian, he managed to mingle with the fascist Nyliaskeresztes members in Budapest. He managed to trick them into making him a member.

In March 1944, the Germans occupied Hungary and ordered Jews to assemble in the town square. Reb Shaya begged his father not to go. His father listened to him, and thus was saved. Many others were much less fortunate. Shaya saw that new tactics were needed at this stage of the war.

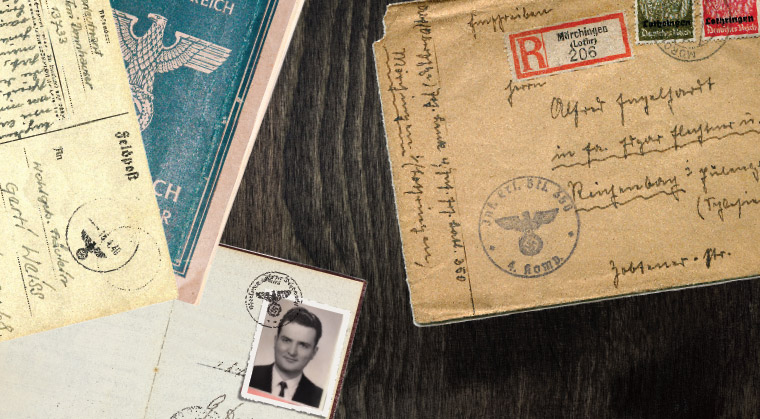

With the help of his fluent German, he was able to finagle a job in the passport office in Budapest. This position afforded him the ability to procure passports and false documents for his Jewish brethren — under the very noses of the Germans.

He also developed a keen sense for being in the right place at the right time, for picking up lifesaving intelligence.

“My father knew where to pick up vital information,” says Lazer. “He would walk miles to be present when plans were discussed. As soon as he heard the name of the town they were planning to raid, he raced there to wake up the Jews and warn them to escape.”

One day Shaya came home to find his father missing. His mother’s clouded face said it all: “The Nazis took him away.”

Shaya learned that his father had been sent to the train station to be carted off to a death camp. Reb Shaya hurried to the train station in his uniform, his boot heels ringing against the pavement as he strode through the milling, despondent crowd, searching for his father. Finally, he spotted his father, grabbed him, and began dragging him away.

“Verfluchtener Jude! Accused Jew!” Shaya spat, as he started to kick and beat him.

Reb Shaya’s father did not recognize this fascist who was accosting him and was shocked, to say the least, to be receiving this “special treatment.”

“Where are you taking him?” demanded a towering SS commander, who stepped into their path.

“Leave this Jude to me!” Shaya guffawed. “I have an account to settle with him and want to have the honor of finishing him off.”

He hustled his father away from the train station and saved his life.

Reb Shaya obtained a three-wheeled motorcycle and immediately set about saving lives with it. He would pick up a dozen loaves of bread daily from the bakery and hide them in the sidecar under mounds of rags and then shuttle them over to the Jewish Ghetto. When the German guards asked what he was carrying, he would reply, “Laundry,” without batting an eyelash.

He worked out an arrangement with his mother whereby he would throw the bundle of bread loaves out of the sidecar, and she would surreptitiously bring them into her house. Then, she meticulously cut the bread and distributed enough slices to sustain 40 to 50 families. Although Shaya’s siblings begged that she save something aside for the family for the next day, she assured them that Hashem would provide what they needed, devar yom b’yomo.

One time Reb Shaya was able to procure a huge sack of beans. His mother lit a massive flame using old book covers from the library to boil those beans. Every person in the ghetto received 15 beans.

After a while, the Nazis caught on to Shaya’s schemes. They saw, for example, that the towns they raided had few or no Jews. Something did not add up. They started suspecting someone in the bureaucracy. After five or six times, their suspicion fell on Reb Shaya Blau in the passport office.

One day they pounced upon Reb Shaya and beat him mercilessly. They interrogated him and then beat him some more. When he felt that he was at his breaking point, a tall, muscular Nazi walked into the office.

“Leave him alone!” he barked. “I’ll finish him off myself!”

The Nazi smacked Shaya in the face and violently threw him out of the office, onto the pavement. Mustering strength he didn’t know he had, Shaya picked himself up and ran for his life. Miraculously he escaped and made his way home — but he suffered from a pronounced limp the rest of his life.

The Blau family chesed still found outlets after the end of the war. Dovid and Rivka Blau, Shaya’s parents, took many orphans under their wings, and tried to give them the most honorable weddings possible under the dire circumstances. They accompanied perhaps 20 couples to the chuppah, and continued to provide love, support, and care even after the wedding. Once an elderly Jew stopped Reb Lazer in the street and told him, “I was a yasom after the war. I had nobody. Reb Dovid and Rivka Blau made my wedding happen and supported me. I’ll never forget it.”

Late in life an extended illness forced Reb Shaya to stay in the hospital. Admiring nurses and doctors learned of his activities during the war and went out of their way to give him the royal treatment. They knew how much he invested to save so many lives and wanted to repay him in kind.

The fruits of his efforts continue to multiply to this day: The four brothers and a sister whom he saved grew up, married, and brought children and grandchildren into the world — more than 200 descendants in all. Thousands of other people alive today throughout the world are davening, learning Torah, and performing mitzvos in his zechus.

His neshamah should have an aliyah and in his zechus we should see the yeshuah bimheirah v’yameinu.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 699)