Message on a Bottle

Matti Dushinsky transformed a challenging childhood into vibrant art

Photos: Eli Cobin

It’s a sunny winter’s day when I make my way through the concrete jungle of Beit Shemesh’s Cheftziba neighborhood to visit artist Matti Dushinsky. The buildings are tall, crowded together, and plastered with apricot-colored cement, some of the facades decorated with Jerusalem stone in a polite nod to aesthetics.

The only indication there’s an artist living in an apartment off this stroller-strewn lobby is the door plaque, covered in green swirls — emerald and lime, forest green and aqua — with Dushinsky inscribed in elegant gold lettering.

Matti’s apartment is small and spartan. A sagging Formica bookcase, a scratched dining room table, and a cracked faux-leather couch are the only furniture in her living room — reflecting her humble beginnings in the alleyways of Meah Shearim.

The simplicity surprises me, I expected an artist’s home to be beautiful, and Matti picks up on that.

“We live b’pashtus,” she explains in Yiddish-accented Hebrew. “But when it comes to art supplies, we invest our money; I only use the very best materials.”

Everything about Matti is out of the box, from her background to her mode of dress to her artwork. She’s the daughter of a Toldos Avraham Yitzchak chassid, but doesn’t wear the traditional black tichel or stockings. Instead, she’s dressed in a turquoise sweater and beret that bring out the green of her eyes, expertly lined in dark green pencil. Her story is one of tenacity and hope, of a woman who pulled herself out of the cesspool she was drowning in and built a beautiful life for herself, climbing rung after rung despite everything pulling her down.

“My life shows that there’s hope for everyone,” Matti says as we sit down on the couch with mugs of coffee. “Don’t ever make assumptions about how your children are going to turn out, because every person can turn her life around. Ein yeiush ba’olam, there’s no despair in the world, isn’t just a pretty phrase. It’s a truth.”

Tough Beginnings

Matti’s childhood was challenging. Although she grew up in a loving, supportive home — the fifth of 13 children, bli ayin hara — she endured several incidents of abuse at the hands of a neighbor, which left marks on her soul.

But what impacted her most, she believes, is the lack of support she had for her severe learning difficulties, which made every day of school excruciating for her. “When I was in one of the younger grades, I traded some treats for a friend’s toy. When my friend’s mother saw she’d come home from school without her new toy, she called the teacher, who accused me of having stolen it. The teacher told my mother, while I was within earshot, that I was a really difficult, aggressive child, borderline retarded, and that nothing would ever become of me.

“My mother took her words with a grain of salt — she knew I wasn’t cut out for academics, but she also knew perfectly well that I was a sweet little girl. But those words devastated me. They reverberated in my head my whole life.

“The teacher virtually ignored me for the rest of the year, and in my childlike perspective, I viewed adults, especially teachers, with suspicion, sure they were the enemy and not there to nurture or guide me. The rest of my school years were awful.

“The smart teachers left me alone to draw and daydream in my seat, and the ones who tried to bully me into submission went through a very hard time trying to keep me in line. ‘Matti, mah yetzei mimech? What’s going to come out of you?’ was something I heard over and over again.

“In high school I made friends with all the bad girls in the neighborhood. But baruch Hashem, my parents were very understanding and never came down harshly. That would have driven me away, into the arms of my bad chevreh. They bought me art supplies and encouraged me to draw, paint, and create. I had such an open relationship with my father that when rebel boys used to drive past me and my friends on their motorbikes and drop notes suggesting we meet up, I always used to show him the notes. It was that positive relationship that stopped me from taking up those boys on their offers.

“When I was 17, my parents decided school was really stifling me, and even though it wasn’t accepted in our circles to drop out of school before marriage, they pulled me out, and I started working.”

“At that point, I hadn’t even been thinking about shidduchim, but my parents were. My husband was suggested, and they liked the idea.

“He was from a small, very closed Yerushalmi chassidus called Mishkenos Haroim, though he wasn’t closed at all, and lived in Sanhedria. I didn’t know what I wanted to do with my life and was very reluctant to meet him. I also had very firm and superficial criteria about what I wanted in a husband: He had to be tall, dark, and handsome like my brothers, and he couldn’t wear a caftan during the week, just on Shabbos. I asked to see him before we went on an official beshow, so my father arranged that he’d walk past our porch holding a Gemara so I’d be able to identify him, and I’d take a look at him from there.

“But he got confused between the different alleyways in Meah Shearim and walked along the wrong street. Eventually he found the right place, and I got a glimpse of a short, blond bochur. But there was something appealing about him, and I agreed to meet him.”

They met for half an hour and were engaged right afterwards. During their ten-month engagement, Matti didn’t see him or speak to him the whole time.

“It was a very difficult time for me,” she says. “If my parents thought I gave them a hard time during my childhood, that was nothing compared to the agony they went through during my engagement. I was very nervous and regretted that I’d agreed to get married.

“But baruch Hashem, all went well. My husband is my biggest supporter. A year after our wedding, we were blessed with a baby girl. When I held her in my arms for the first time, I thought, ‘Everyone always wondered what was going to come out of me, and look what a beautiful being I produced.’ That really empowered me. I really took to motherhood, and looking after my baby was very good for my self-confidence. I saw I was able to do something positive, to succeed.”

Another baby girl was born a year later, and then four boys in the years after that, including the two-week-old she holds in her arms as we speak, and the blue-eyed two-year-old who keeps asking to hold the baby, and whose face lights up when Matti lets him.

Beginning to Heal

“A few weeks before I gave birth to him,” Matti says, as she points toward the baby, “I was feeling very emotional. I stood in front of the mirror and tried to access the little girl inside of me, the little girl who believed she was an efes, a nothing.

“I knew I was good at mothering, and that this little girl needed a loving adult to reach out and nurture her. I couldn’t stop crying as I coaxed her out of her hiding place, out of the pain she was wrapped in. It was the most liberating experience and felt like a milestone in my journey to healing.

“Another powerful experience was several years ago, when my husband did NLP on me. He’s an NLP practitioner and works at Seeach Sod, a school with children with special needs, in Yerushalayim. He treated me like his patient, sat opposite me, and tried to uncover what was stopping me from being a happy person.

“That was when I fully acknowledged my rage at the teacher who I felt destroyed me. My weeping was so intense, my husband suggested I write her a letter explaining to her what she’d done. It was very therapeutic, and I actually sent her the letter.

“She was shocked to receive it. She said she didn’t remember the incident, but apologized nonetheless and explained she was very young and inexperienced at the time, only 19, and that today she’s a far more emotionally in tune teacher, and would never, ever speak to or about a child like that.

“She also said she had a very hard time having children, and that throughout all the years of infertility, she and her husband thought someone must have had a hakpadah against one of them that was causing the nisayon. They’d wracked their brains trying to figure out whom she or her husband had wronged so badly. When she got my letter, she realized it was me, and she asked me for mechilah.

“It was a difficult position to be in. She’d hurt me so much and I’d carried that anger and pain inside me all those years. Did I have the ability to forgive her? I wasn’t sure.

“But I knew forgiving her would help not just her, but also me. It took a lot of effort, but I think I did it wholeheartedly.”

Birth of an Artist

“After we got married, I worked as a gannenet, and then as a secretary at a medical clinic. I found both jobs so boring. I wanted to do something artistic. I trained as a makeup artist, but even though that involves color and using brushes, it didn’t speak to me.

“Then I saw an ad for a graphology course. I didn’t even know what graphology was. I confused it with graphic arts, and I signed up for the course, hoping the design aspect of graphics would satisfy my artistic side.

“It may not have been graphic arts, but graphology fascinated me. I learned so much about emotions and the human psyche. That was the beginning of my journey to find myself and heal. There I was, Matti who was always the worst student, and this time I was the first to arrive at the class, the last to leave, sitting in the front row and taking notes. I loved it and worked in the field for a while, but it’s quite time-consuming, and you really have to work hard to analyze writing.

“At the same time, I finally felt confident enough to paint, really paint. I wasn’t interested in studying art — my experience with teachers had been so negative, I thought studying would crush my artistic ability, not help it flourish. Everything I do is self-taught. As I developed my artwork, I stopped doing graphology so I could focus all my efforts there.

“Most of my art is spontaneous. I find I’m less successful when I plan a piece, and I only draw first in pencil when I’m commissioned to do something and it needs to turn out according to their vision.

“I’m in the middle of a painting now for the maternity ward in Assaf Harofeh Hospital. When I gave birth there two weeks ago, I approached the head of the department and told him I wanted to create a painting for the entrance. They’re trying to attract chareidi patients, so he was very interested in something from a chareidi woman. I’m going to paint three sets of hands — smooth, slightly wrinkled, and full of wrinkles and veins — holding on to the same newborn. It will symbolize that new generations are created here, and a hospital can be part of a family tradition.”

The outline of the painting, in pencil, hangs over the couch.

“Usually, I paint from my heart, from my soul,” Mati explains. “One of my first paintings was a Holocaust painting. It really captured the trauma of being the granddaughter of survivors.”

She takes me to the hallway, where the painting is leaning against the wall. It’s chilling. In the center is a young blonde-haired girl, face in her hands, weeping. Underneath is the word Jude, written over what looks like flames, explosions of yellow, orange, and red. Jude looks like it’s dripping ink, dripping blood. At the top of the painting is a forest, with railway tracks twisting and turning.

“Those train tracks lead to nowhere. They reflect my confusion,” Mati explains. As a third-generation survivor, I completely understand.

“Three of my grandparents are survivors, from Hungary. My grandfather, also originally from Hungary, was learning in Eretz Yisrael under Rav Yosef Tzvi Dushinsky ztz”l. It was time for him to return home to settle down and marry, but things were looking very bad in Europe, and Rav Dushinsky told him it was dangerous to return. He stayed, and was the only one of 18 siblings to survive the Holocaust.

“My grandfather was a clean-shaven lawyer, but he was attracted to the chatzer of the Toldos Aharon Rebbe. However, he couldn’t grow any closer to the Rebbe and become part of the exclusive chabirah because my grandmother wore a sheitel and light stockings. There was no way my grandmother was going to change the way she dressed.

“But then, during the Yom Kippur war, the Arabs were shelling Yerushalayim, and my grandmother was terrified. She got out of bed and went to daven in the living room, and made a deal with Hashem that if they survived this war, she’d begin wearing a turban and black stockings. Well, just then there was a boom, and a shell landed on the bed where she’d been lying not long before.

“After the war ended, she was very apprehensive about implementing the chumrah she’d promised to take on in a moment of panic, but a promise is a promise. That’s how my family became Yerushalmi chassidim. When Toldos Aharon split in 1996, my father chose to affiliate himself with the Toldos Avraham Yitzchak faction.”

Every Surface a Canvas

Matti leads me to the children’s bedroom and points to two rows of white rectangular shapes pressed between the crib and the wall. For an instant I think they’re spare crib mattresses, until I realize they’re canvases, their painted side facing the wall to protect them from damage.

Matti pulls out a few to show me. There’s a distinct theme running through her pieces: dancing men in flat shtreimlach and caftans, little boys with long peyos and pom-pom-tipped kopelach in the alleyways of Meah Shearim, archways, wrought-iron stairwells, and makeshift laundry lines all part of the scene. Most of these paintings are done in shades of one bold color: purple, burgundy, blue.

There’s one painting that’s unusually arresting. Done entirely in orange and yellow, Matti painted it on honor of one of her wedding anniversaries. At the top of the painting is a young bearded violinist, his head resting on his instrument, the reverence and concentration he’s playing with captured on his face. Underneath him are a Yerushalmi chassan and kallah in the midst of a mitzvah tanz, hands clasped. Looking at the picture, you can sense the holiness of the moment. The couple appears to be standing atop one of the stone walls of the Old City, Migdal David in the background. A border of small Yerushalmi stones completes the picture.

“This isn’t a realistic picture,” says Matti, and goes on to clarify. “Yerushalmim don’t have music at weddings, zecher l’Churban. Just a drummer. A violinist wouldn’t be there. We’re allowed have music at home, and at Simchas Beis Hashoeivah, but not at weddings or bar mitzvahs. But I don’t stay true to reality in my paintings.”

She points toward another painting, this one hanging in a niche over the hallway sink. A man in a caftan and shtreimel is dancing in a swirl of orange and red, but he’s barefoot.

“I painted that recently, after we went to my niece’s wedding. Her grandfather was dancing with such abandon, I had to paint him. That abandon is reflected by him being barefoot. In reality, he’d never take off his shoes in public.”

One thing that strikes me about all of Matti’s paintings of Yerushalayim is that there’s always a stray cat in the corner. I ask her about it. She laughs.

“Yerushalayim is notorious for the stray cats that slink about. Everyone hates them. But I always identified with them, with being disliked, unwanted, and alone, so a cat always makes an appearance in my paintings of Yerushalayim.”

Matti flips open a ring binder lying on the dining room table. Inside are plastic files filled with cut outs from magazines and circulars. She shows me a picture of two Yerushalmi boys holding hands and walking through a stone courtyard. They look familiar; they’re the same two boys who feature in one of her paintings.

“There they are in real life,” Matti says with a laugh, while pointing out the canvas.

“I paint on any surface that appeals to me,” she says and shows me the hairy shell of a coconut that’s now colorful instead of brown. “We had this left over from Tu B’Shevat, and I just had to try it out.”

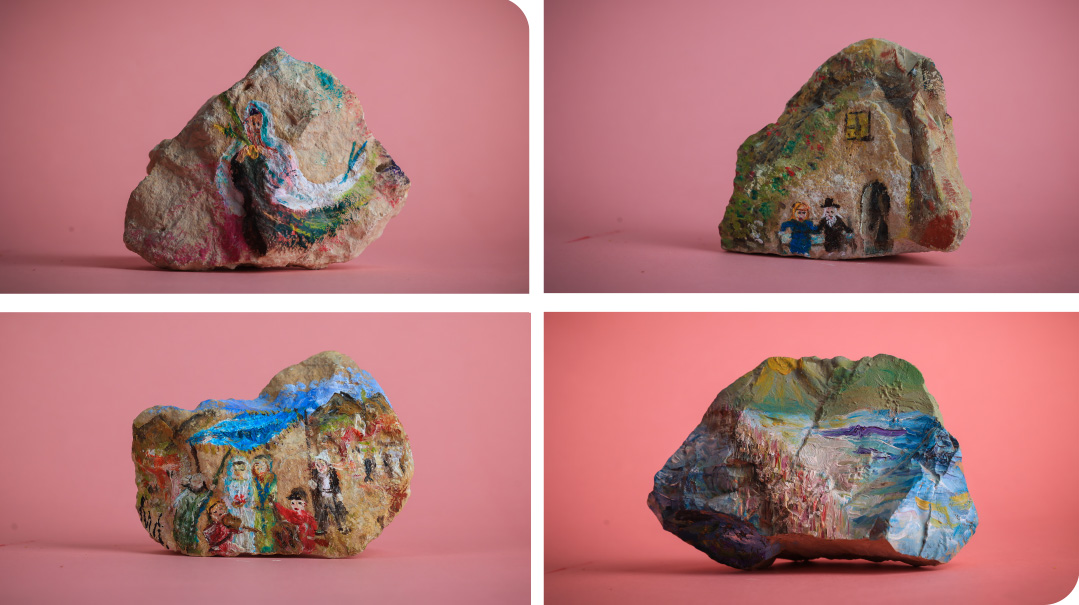

In the spare bedroom, there are rows of rocks lining the desk, each with a tiny, meticulously painted picture on them. They’re magnificent and charming at the same time. There’s Kri’as Yam Suf the walls of water in various shades of blue and green, tiny people in robes and shawls, some holding canes, passing through. Then there’s the sweetest painting of an elderly couple sitting on a bench next to an arched doorway, beneath a canopy of flowers and those small barred windows typically found in the Old City. They remind me of the pasuk, “Od yeshvu zekeinim v’zekeinos birchovos Yerushalayim.”

“Where do you get the stones from?” I ask.

“Outside,” Matti answers. We go to the window. Her apartment is at the edge of the neighborhood, and just beyond lie grassy hills, strewn with stones. “I just go out and pick them, like flowers,” she says with a smile.

Branching Outward and Upward

Matti’s most recent project, and her main focus today, began a year ago. She’d just entered the world of art galleries, and almost secured some contracts, when Covid hit. Galleries were forced to close and weren’t in a position to showcase new artists.

There was a lull for a while, and Matti wasn’t sure what her next step would be. Her family has a minhag to keep the bottle of wine used at a child’s bris as a segulah, and one afternoon, restless, she took down the bottle of wine from her one-year-old’s bris and tried painting on it. She liked the results, and began refining the process and the style until she had developed something exquisite.

“I can’t tell you much about my methodology,” she says with a smile. “It’s a secret formula, just like Coca-Cola has a secret recipe, I have a secret formula. I usually paint with oil paint, but this uses a mixture of materials. I remove the sticker from the bottle of the wine and wash and dry it well, and then begin painting.”

The wine-bottle paintings reflect her signature style of colorful, joyful Yerushalmim in shtreimlach dancing, as well as quaint scenes from Meah Shearim or its skyline. She also features clowns, in the spirit of Purim.

Matti traces a clown with her finger.

“You see the detail in this one?” she asks.

From far, it just looks like a clown. But up close you see the clown’s long eyelashes and mesmerizing eyes, and the bow tie that peeks out from among the swirls and spots.

Somehow, even without social media to promote her, Matti’s wine-bottle painting took off, especially in America. She’s had orders from noted askanim who send her painted wine bottles as gifts to wealthy business associates and political figures.

She recently registered as an official business, and is developing the logistical and marketing sides of her fledgling enterprise. She also has a knack for writing powerful and emotive marketing copy describing each of her creations, and is full of enthusiasm about expanding this painting-on-a-whim into something serious.

“You need to understand what a miracle this is,” Matti says to me earnestly. “When I was a child, most people believed I was hopeless. I was tottering at the edge of complete rebellion, ready to get on the back of a motorcycle with a strange boy and throw my life away. I had zero self-confidence. I couldn’t even say a kapitel of Tehillim because it was too hard for me to read.

“Now, I’m a loving wife and mother of young children. I say ten pirkei Tehillim every day, I’ve picked up English, can do basic math, I’ve painted tens of gallery-worthy paintings, and have just opened a business catering to prestigious international customers.

“Never give up on yourself. And never give up on your children,” she emphasizes. “You can’t judge someone’s potential. You just don’t know how they’ll turn out.”

(Originally featured in Family First, Issue 784)

Oops! We could not locate your form.