Message Not Sent

Is Eylon Levy a cautionary tale of a spokesman exceeding his mandate, or a parable for the crippling failings of Israel’s PR machine?

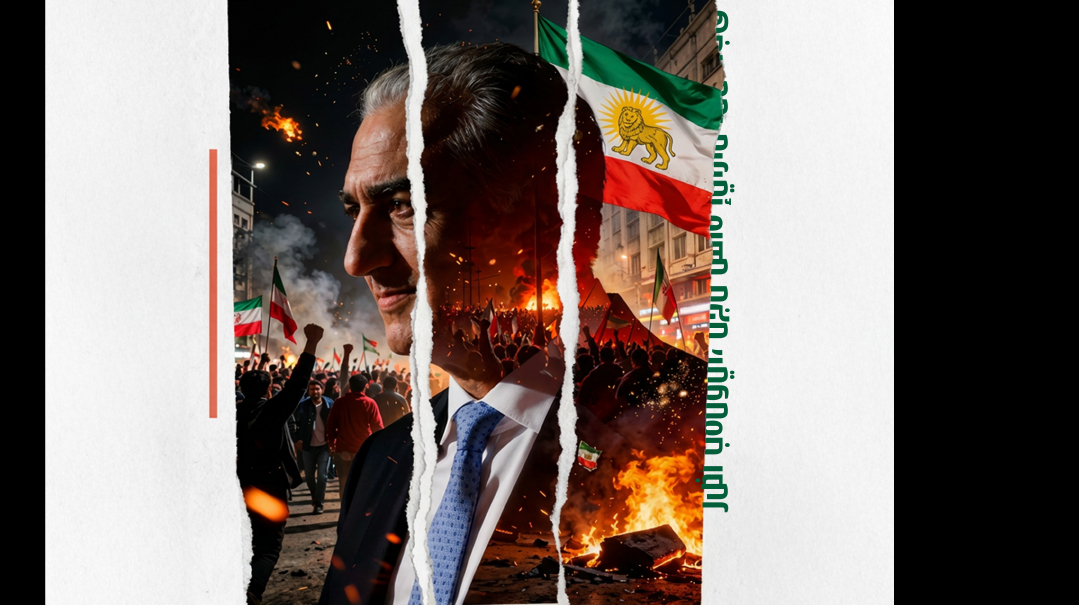

Photos: Ariel Ohana, AP Images, Flash 90

Last November, Eylon Levy became famous for his eyebrows. The London-born media professional was serving as a volunteer wartime spokesman for Israel as the November hostage deal was unfolding, when a British interviewer asked a jaw-dropping question.

“I was speaking to a hostage negotiator this morning,” the Sky News anchor said, “who made the comparison between the 50 hostages that Hamas has promised to release and the 150 prisoners that Israel has promised to release. And he asked whether Israel doesn’t think that Palestinians lives are valued as highly as Israeli lives?”

It was a shocking question — both fatuous and bigoted. As the presenter got to the end of her challenge, the split screen showed that it had shaken Levy’s calm demeanor. His eyebrows began to arch, his eyes opened wide as he stared back at the camera and there was a stunned pause, before he fired back.

“That is an astonishing accusation,” he said. “If we could release one prisoner for every one hostage, we would obviously do that. These are people with blood on their hands. It’s outrageous to suggest that the fact that we’re willing to release many prisoners to get our children back means that we don’t care about Palestinian lives. Really, it’s a disgusting accusation.”

Within hours, the exchange and particularly the raised eyebrows had gone wild online, and Eylon Levy became a celebrity in the pro-Israel world.

This anecdote from the prehistoric era at the war’s beginning, when Israel still got a hearing of sorts in media outlets, is instructive in terms of what came next. Because within months, he was gone. The official story was that Levy had made a comment offending the British government. However, according to Levy, the real reason lay more with local power dynamics — i.e., displeasure from within Bibi’s inner circle — than any supposed bilateral grievance. Perhaps another way of putting that is that Eylon Levy became the story, not the spokesman. Colleagues seem to think so.

“Eylon comes with a very interesting package,” says Peter Lerner, an English-speaking spokesperson for the IDF. “He is both social media savvy and has a very sharp tongue. I think that’s why he rallied Jews around the world and also Israeli society. But part of his downfall came because he became the story rather than communicating Israel’s story.”

Whatever the immediate trigger, Levy’s tale of short-lived PR superstardom could serve as a parable for Israel’s wider hasbarah PR efforts. Here was a media champion who is quick-witted, charismatic, and — as the eyebrow meme proved — perfectly suited for the online era. Why had politics led to his ouster? Levy’s story also raises the opposite possibility: Given the tidal wave of anti-Israel hatred washing through the online and media worlds, one more or less talented spokesman may make no difference anyway.

Free from the role that made him a celebrity, Levy feels more comfortable critiquing Israeli communication strategies. He condemns what he sees as “improvisation” in one of the country’s most sensitive areas, where he thinks that professional spokespeople can still make a difference to all but anti-Israel radicals, and says that Israel is at least partly responsible for its current straits due to the tremendous communications blunders it has made since October 7.

And back in the private sector, where he was until the Hamas attack plucked him from obscurity, Levy admits: “I would return to my post in a heartbeat.”

Preach to the Choir

As sure as the surge of patriotism that accompanies every war in Israel is the wave of criticism that emerges when Israel’s hasbarah effort fails. This time around, the real-world implications of the PR failings have been sharp: arrest warrants issued by the prosecutor for the International Criminal Court for Prime Minister Binyamin Netanyahu and Defense Minister Yoav Gallant, and recognition of an independent Palestinian state by Norway, Spain, and Ireland. Eylon Levy thinks that although most of Israel’s international opposition is based on malice and fueled by ignorance, the country bears a share of the blame for its own setbacks.

“The accusations against Israel are completely detached from reality,” Levy declares. “It’s clear that the human rights agencies are running a coordinated campaign to put political pressure on Israel, even if it means lying to the International Court of Justice. And that is what they are doing. But we could have fought back better.”

Levy identifies one winning strategy that ought to be achievable, in a country populated by immigrants from every corner of the globe.

“We do not have spokespeople fluent in the necessary languages,” he says. “There is no one who is going on TV and speaking in Spanish with the authority of the government of Israel. Norway recently made the insane decision to recognize a nonexistent Palestinian state, on the rationale that it’s really an anti-Hamas move. And it makes absolutely no sense. But we have to take a share of the blame. Because we have not put anyone in front of TV cameras to speak to the Norwegian public in their own language. So is it any wonder that we’re losing the battle? We’re not even fighting.”

Public opinion has long been recognized as a battlefront in wartime, but the wide spread of social media has made that arena paramount. Levy asserts that, just as it was tragically demonstrated on October 7 that the Israeli Defense Forces are fallible, the Israeli government’s PR abilities were also shown to be lacking.

“Israel was completely unprepared to fight in the public relations arena,” he says. “When this war erupted, the Prime Minister’s Office did not have a department responsible for the international media. That was something that had to be set up on the fly. Thanks to some very talented people, and lots of volunteers from Israel and the diaspora, we managed to cobble together a professional operation.”

Not everyone agrees that Israel has a hasbarah problem. Some argue that no matter how clearly Israel states its message, the haters will always find an excuse to blame the Jewish People. As commentator Richard Hanania wrote in a recent opinion piece in Tablet magazine, “Those who think that the problems Israel is facing result from a flawed diplomatic approach should spend some time thinking about how Hamas presents itself and its ultimate aims. One reason that the atrocities of October 7 are undeniable is that Hamas fighters wore GoPros as they slaughtered innocent women and children … yet all this is ignored because it does not fit into the anti-Western, Third Worldist, or antisemitic narratives most of the international community is committed to for one reason or another.”

Similarly, Dr. Esther Lopatin from Tel Aviv University told Calcalist, “We thought if we told the world what was happening, people would understand us and show understanding for our side, or understand that [this conflict] is not black and white but rather much more complex. Unfortunately, we failed because people are not always interested in hearing your side, even if you show them the truth and provide them with facts.”

But Eylon Levy insists that only the extremists hold fixed opinions on the Middle East issue, and that communications work is essential, not only to reach the vast under-informed public but also to strengthen the arguments of Israel’s supporters, both Jewish and non-Jewish.

“It’s important to preach to the choir, because if you don’t preach to the choir, it won’t sing,” Levy says. “You need to talk to your supporters so that they know how to talk to the outside world. But I think also that the people in the middle can be swayed. There are people who have made up their minds, and it doesn’t matter what you say — you are never going to change their minds. But most people don’t wake up every morning and go to sleep every night thinking about Israel. They don’t have firm opinions. They can still be won over. It’s still possible to change their impressions.

“So if you have a situation, for example, where Egypt is blocking the Rafah border crossing, it’s not letting trucks reach Kerem Shalom, which Hamas is continuously bombing, we have an opportunity to tell a story about how Israel is trying to get aid into Gaza. But Egypt and Hamas are blocking it. And we have to be able to be more aggressive on that in the way that the state isn’t doing, by the way.”

Unarmed Combat

Eylon Levy’s ringside seat to the inner workings — or dysfunction — of Israel’s PR machine gives his critique unusual teeth. “We went into TV interviews only with general messages,” Levy relates. “We did have access to the latest official facts and figures, and access to statements that the prime minister and the army had made. But we were not given the more thorough research and fact-checking and legal advice, ammunition that you need in order to fight.”

Corollary to this is Israel’s failure to engage in “public diplomacy” — that is, a government-sponsored effort aimed at communicating directly with foreign publics, essentially going over the heads of their leaders and their media. The main problem, he says, is that no one has identified this lack as a funding priority. “The state budget,” he says, does not include anything for public diplomacy to the international media. It doesn’t exist.”

For Levy, these shortcomings are as deplorable as failed security mindset that led to October 7. “As part of the prime minister’s promise to take responsibility and offer full accountability for the war, I think the government will also need to answer to the public about how Israel’s communications were so completely unprepared,” he asserts.

I asked Levy what he would do if he were put in charge of the government’s communication team.

“First of all, Israel needs an elite force of spokespeople in every language,” he says. “There has to be a government spokesman in English, French, German, Arabic, Persian, Spanish, Portuguese, and, as far as I’m concerned, Swahili and Swedish. They need to be available in every time zone. And they have to be centrally briefed, available to give interviews, able to speak with the authority of the government. We have to be everywhere that we are being attacked and to return fire.

“The second thing,” he continues, “is that public diplomacy has to be like a crisis communications war room. You need to take someone with experience in funding crisis communications and dealing with the media from the military. And to scale it up to a national civilian level. We have to correct every newspaper, every TV report, every time they say something against Israel, and to demand a retraction, to demand the correction. This is not happening.

“And the third thing is that we have to be better at mobilizing the diaspora. Giving them the information and messages they need. More than that — suffusing them with the pride and inspiration that they need to want to be part of our story. Because sometimes Israeli ministers and politicians say stupid, ugly things that only push diaspora Jews further away and make it more difficult for them to support us.”

Eylon Levy is not alone in holding these opinions. IDF spokesperson Peter Lerner echoes Levy’s military terminology when he says that Israel must convey its narrative in three “battle spaces.”

“First of all, our presence in the traditional media needs to be engaging, authoritative, informative, but also sincere,” Lerner says. “There needs to be a level of humanity expressed for the general public. Most viewers, listeners, or readers are under-informed, but aren’t necessarily key supporters or detractors of Israel. So you need to be appealing to them, likable to a certain extent.

“Then you must engage in the battle on social media. Silence in the social media battlespace is not an option, because if you’re silent, you’re ceding the battleground to the enemy, not participating in the conversation.

“The final battlespace for media or public relations efforts is public diplomacy. This involves engaging with governments, organizations, and influencers not directly connected to media or social media but who influence and drive diplomacy and support for Israel around the world. Victory in all these battle spaces is essential.”

Using His Elbows

Born in London to Israeli parents, Eylon Levy was just 21 years old when he got his first taste of media exposure. He was a student in philosophy, politics, and economics at the University of Oxford and joined its famous debate team, the Oxford Union. When the opportunity arose to confront the notorious anti-Semitic MP George Galloway, Levy leapt at it.

The debate topic was “Israeli occupation of the West Bank.” After Galloway’s ten-minute opening statement calling for the West Bank to be made Judenrein, Levy took the podium to defend Israel’s stance. For reasons he still doesn’t fully understand, Levy repeatedly referred to Israelis as “we” instead of “them.” This did not go unnoticed by Galloway, who’s a skilled debater.

“You said ‘we,’ ” Galloway noted. “Are you Israeli?” After Levy affirmed that he was, Galloway stood up and declared, “I don’t recognize Israel and I don’t debate Israelis!” With that, he stormed out of the room, triggering headlines for young Levy.

The subconscious identification with his Israeli heritage was an outgrowth of Levy’s traditional upbringing; he would probably fit into the mold of masorati in an Israeli context.

“I went to a Jewish primary school, Naima, the Sephardi primary school in London,” says Levy, now 33. “That gave me my formative grounding in Jewish education. After that, I was at a school that wasn’t officially Jewish but had so many Jewish kids that it closed every year on Yom Kippur because there weren’t enough students to keep the school running.”

Levy describes the religious identity of his home as “somewhere on the secular to traditional spectrum,” though he emphasizes that he grew up “with a very strong Jewish and Israeli consciousness.” His parents, who were both born in Israel, made sure of that.

“It’s impossible to escape when you have a Hebrew name,” he says. “There’s no hiding it, my name isn’t Andrew. So although I grew up feeling very British, I was also essentially a second-generation immigrant. We spoke Hebrew at home, and we all have Hebrew names. Like many Jews, it was a question of growing up with a hybrid identity.”

A turning point for Levy came in 2014, when he traveled to Poland to participate in the March of the Living. “I remember being in Auschwitz after a very difficult week, learning about the Shoah with a survivor on the bus, standing in the ceremony, meters away from the rubble of the gas chambers and crematorium, wrapped in an Israeli flag, trying to sing ‘Hatikvah’ and choking on my own tears, and realizing that the decision had been made for me.”

At 23, during the 2014 Gaza war, Levy enlisted in the IDF and served on the staff of the Coordinator of Government Activities in the Territories (COGAT). “We were basically the point of intersection between the Palestinian Authority, the Israeli authorities, and international organizations,” he explains.

Growing up, Levy never thought he would work in media, and he now says his career came about “almost by chance.” After two years in the army, he decided to stay in Israel, uncertain about his next steps, when he heard that the new Israeli Broadcast Authority was looking to expand its staff. They needed a new anchor for their daily English-language show.

“I went, did a screen test, and they took me,” he says.

Levy’s early days on camera tease the formidable media operator he was to become. In a 2016 interview that garnered attention, an almost boyish Levy cornered the then-EU ambassador to Israel, Danish diplomat Lars Faaborg-Andersen, demanding he condemn the European Parliament’s ovation for Palestinian Authority president Mahmoud Abbas. Levy’s ability to articulate and defend his ideas without flinching was evident even then, when he was a novice facing a seasoned diplomat.

Levy took a number of jobs after making aliyah to pay the bills, such as translating books from Hebrew to English. One of his clients was Rotem Sella, publisher of the conservative imprint Sella Meir Press — a connection that would later prove fateful.

In the meantime, Levy made a first, unsuccessful attempt to join Prime Minister Netanyahu’s team, after then-foreign media advisor Mark Regev was appointed ambassador to London.

“Netanyahu’s office announced they were looking for a new international spokesman,” Levy relates. “I put myself forward and got to the second stage of interviews. In hindsight, it’s a good thing I didn’t get the position then, because I was far too young and inexperienced for the role.”

But this setback didn’t stop him from pursuing political roles. In 2021, he used his contacts, and by his account, his “elbows,” to secure the position of international media advisor at the office of newly elected president Isaac Herzog.

By the age of 30, Levy had demonstrated skill not only as a communicator but also as a player in the power and media game. In a remarkably short period, he had gone from someone unsure about a career in journalism to becoming the English voice of the president of Israel. However, he had not yet reached the pinnacle of his exposure. The journey that would take him there would be far more vertiginous, and in some ways, ruthless.

Only in Israel

Although Eylon Levy is quick to condemn Israel’s failures to prioritize a public relations strategy, he readily admits that he was one of the primary beneficiaries of this lack of professionalism and foresight — factors that propelled him into the role of government spokesperson.

“Mine is a story about the best of this country and the worst of this country,” he says. “An ‘only in Israel’ story, where you can go from giving interviews in your living room to standing behind a lectern emblazoned with the Prime Minister’s Office seal in the span of 24 hours.”

When war broke out on October 7, Levy was unemployed. He deftly sidesteps details about his departure from President Herzog’s office, noting only that the conflict with Hamas found him “taking a break to work out my next steps.” Levy watched as Israelis put aside their differences to help in any way they could.

“Within three days of the massacre, I realized, ‘Okay, I know how to do media. I have experience — five years as a TV news anchor, two years doing international media for the president. We are the only story in the world right now. Everyone wants to hear what’s happening in Israel. So I’m going to give interviews.’”

Levy displayed his social media savvy to get his next job. “I took a pile of books, set them on the living room table, put the laptop on top, took that bottle of protein powder, put the lamp on top of it. I took a picture and tweeted it, saying, ‘Hello. I’m a former adviser to the president, and I’m available to give interviews.’”

Levy’s earlier connection to the publisher Rotem Sella now came into play. There was a growing sense that Israel’s PR operation had no one at the wheel, despite the country having a very media-savvy prime minister in Binyamin Netanyahu.

“Rotem Sella noticed this communication problem and began to pull strings and connections to set up a public diplomacy operation that would support the state,” Levy says. “The Prime Minister’s Office called me and asked whether I wanted to come on board. I said, ‘Of course. Absolutely.’ And to cut a long story short, within a week of the start of the war, I found myself in a suit and tie, going on TV as an Israeli government spokesman.”

Acting as a public face of the State of Israel inevitably means facing journalists sympathetic to its enemies’ narratives. “The most hostile interviews were, in fact, from Arabic media,” Levy recalls. “I remember one where they took me in simultaneous translation on Dubai Sky News Arabia. It was quite aggressive, but that’s to be expected. It’s in the West that it’s disappointing to see so much hostility, because you often find an automatic willingness to believe anything Hamas says and disbelieve everything Israel says.”

Eylon made an immediate impact in his new role. He was a fresh face, extremely well-prepared for debate (thanks to his years at Oxford), and possessed undeniable charisma. Before long, he was known. But he was yet to become “famous.”

Raising Eyebrows

On November 23, 2023, a little over a month after Levy was officially appointed as government spokesperson, the “eyebrow encounter” happened.

“I had given 150 interviews before that, but Israelis hadn’t noticed,” Levy says. “This moment went viral. And the reason it went viral was that it struck a nerve. It highlighted the feeling that no matter what we do or say, there will always be people against us. It struck people as completely deranged that anyone could suggest that our willingness to put violent criminals on the street to free babies from captivity was a sign that we are the bad guys and something is morally wrong with us.”

Although the question was brazenly offensive, the video went viral primarily due to Levy’s ability to recognize and seize the moment. His reaction was calculated. He knew this could have a significant impact.

“As she was asking the question, I was thinking, ‘Where is she going with this? No… she’s not. Yes, she is! She really is! Okay, this is a moment of TV gold. You need to do something… on the count of three, pull a face!’” he recounts. “And I remember thinking, ‘Hold it, hold it, hold it as long as you can’ because I realized that I could cut the clip and it would do well.”

That blow-by-blow account is an insight into Levy’s savvy understanding of how to leverage the analog era TV interview using the digital world. The millions of views and shares of that encounter turned him into a meme, someone instantly recognizable. Within two months in his new role, Eylon was famous. “Months later, I still get stopped on the street by people asking for a selfie with the eyebrows.”

But like a hot share hitting its peak on a Wall Street stock chart, that moment marked a turning point. Eylon Levy was no longer just “the government spokesperson”; he became a recognizable figure with a name and a face. At the pinnacle of his personal glory, some perceived that something was amiss.

On March 19, Eylon Levy was suspended “indefinitely” from his role as government spokesperson. The official explanation was that he had made a comment that offended the British government. Foreign Secretary David Cameron had demanded that Israel allow humanitarian aid trucks into Gaza. Levy responded by tweeting: “I hope you are also aware there are NO limits on the entry of food, water, medicine, or shelter equipment into Gaza, and in fact, the crossings have EXCESS capacity. Test us. Send another 100 trucks a day to Kerem Shalom and we’ll get them in.”

According to circulating reports, the British government sent an official letter protesting Levy’s actions. Levy tells me he never saw this letter.

“In a properly functioning country, the response to the British would have been, ‘Yes, the spokesperson’s statements that there are no limits on the amount of humanitarian aid that can enter Gaza reflect government policy and the facts,’ and that would be the end of the issue,” Levy asserts. “But instead, the public diplomacy directorate left me hanging.”

Levy attributes his firing to simple politics. He is not shy about sharing the fact that he participated in the vociferous protests on Tel Aviv’s Kaplan Street against the government’s attempt at judicial reform.

“We ended up with the surreal situation where someone who, until only a few weeks earlier, had been protesting against the government, suddenly became its face to the international media,” Levy told me. “But at the beginning of the war, the prime minister said, ‘B’yachad nenatzeach,’ together we will win. It seemed obvious that if I had put politics aside to join the state of emergency, the government would embrace others who did the same. I thought it wasn’t a secret. People knew, but no one cared.”

Levy’s belief that his dismissal was based on politics was supported by what he heard later. “After telling me I was suspended until further notice, no further notice came. Meanwhile, someone in the Prime Minister’s Office was briefing the media against me. I learned from Channel 12 that a decision had been made to remove me from my position. This was something I found out from the news. It became clear to me that this had nothing to do with the British. It was obviously a pretext.”

Some Israeli media reports suggested that once Sara Netanyahu learned about Levy’s participation in the protests, she demanded his head. But some voices within government communications hinted that not everyone was pleased with the character Levy had been playing.

Famous spokespeople are an anomaly. Anyone who has tried to talk to a spokesperson knows there are multiple protocols to follow. It’s not as simple as picking up the phone; there are permissions, press officers, bureaucracy. On the extremely rare occasion when a spokesperson speaks his mind, it will only be “off the record” — a quote that cannot be attributed to a named source.

Eylon’s problem was that he had become a star — to the extent that rumors started flying that he received an offer to appear on a TV reality show. He confesses that the rumor was true.

Levy doesn’t deny that his high profile might have contributed to his dismissal. “The prime minister had never had an Israeli media spokesperson whose job is to give interviews on camera or hold White House-style press conferences. One analysis is that the prime minister didn’t want anyone else being the face of his government. He wanted to control communications. So whether I was sidelined because of anger over Kaplan Street, or because I was suddenly receiving so much media attention, I really don’t know.”

Paying the Price

Despite his fall from official grace, Eylon Levy still has many powerful friends — evidence of his ability to impress the right people.

“Eylon Levy is one of the most skilled and capable spokespeople in Israel,” says Amichai Chikli, Israel’s minister of diaspora affairs and social equality.

Chikli keeps Levy connected to the current government by funding the podcast “State of a Nation” through his ministry. The podcast’s profile is much lower than that of an official government spokesperson, but the platform allows Levy to fully embrace his role as a media star. (The podcast was launched while Levy was still serving in his spokesperson role, which might have contributed to the irritation felt by higher-ups over his fame.)

The government’s gamble on such projects reflects the necessity of getting the message across by any means. The war that began on October 7 showed that being in the right is often not enough; communicating that effectively to the public is crucial. Chikli is convinced that Eylon is one of the few who can succeed in this task, though he admits it’s a tough battle.

“We are a minority compared to the many forces backing the Palestinian narrative, not just in the Arab world but also in sectors of the left,” Chikli says. “But we must remember we still have allies, brilliant communicators like [British journalist] Douglas Murray and even those like [American comedian] Bill Maher.”

In addition to his participation in the podcast, Eylon has launched his own initiative, which he calls the “Israeli Citizen Spokespersons’ Office.” The project is still at an early stage and is still in the process of gaining followers. The difficulties in managing such a project will no doubt increase Eylon’s awareness of how hard it can be to go it alone. But for now, he is undaunted.

“We are building a team of elite spokespeople to give briefings live on all social media platforms every day with a Q&A,” he says. “We want to be the address where supporters around the world can tune in, get the information they need, and the talking points and messages they need in order to fight back against the hate and propaganda, because the diaspora has woken up. It’s an incredible force multiplier. And Israel needs to be much better at mobilizing the diaspora, because our fight is their fight.”

When I ask him what qualities a good spokesperson should have, Eylon doesn’t hesitate, throwing out a formula in a series of soundbites.

“You need an ability to rapidly assimilate information. You need an ability to think quickly on your feet. You need an ability to speak eloquently and succinctly and frame sound bites. You need an ability to simplify complex issues. And you need a lot, a lot of stamina.”

His own meteoric rise and fall means that Eylon Levy faces a long road ahead trying to build his own citizens’ hasbarah effort without state resources, and without the mega microphone that he briefly held. Stamina is a quality that he’ll need in abundance.

As Israel faces international isolation in a war that seems to have no end, Levy echoes the age-old call of those who bitterly decry Israel’s ramshackle communications. More urgently than ever after October 7, he says the country needs to learn the cost of underinvestment in PR.

“If we want to fight back, if we want to win the communication war, Israel has to invest what it takes.”

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 1016)

Oops! We could not locate your form.