Meet…Michelle Margolis

| August 8, 2023Librarian Michelle Margolis believes that everyone can love history...if they just know where to look.

Always a Booklover

I joke that I became a librarian because I was bad at math, but truth is, I’ve always loved books. After seminary, I studied history at a local university, and for pocket money I looked for a job at the college library. I walked into the Special Collections Department and said, “I like old books — can I work here?” That’s how I landed my first library job.

While I enjoyed the work, I wasn’t connecting with the books on a deep level because they didn’t speak to me personally. My boss encouraged me to earn a library degree and find a job at an academic library with Jewish books. Her advice led me to a summer internship at Baltimore Hebrew University (an institution that no longer exists). My job there was to sort through books that BHU had received through the Jewish Cultural Reconstruction project (JCR).

Touching History

After World War II, the US Army discovered warehouses filled with books that had been confiscated by the Nazis, yemach shemam, and the JCR was later established to return the books to their former owners. But millions of these former book owners were no longer among the living, so the JCR sent the books to libraries servicing Jewish communities, mostly in the US and Israel.

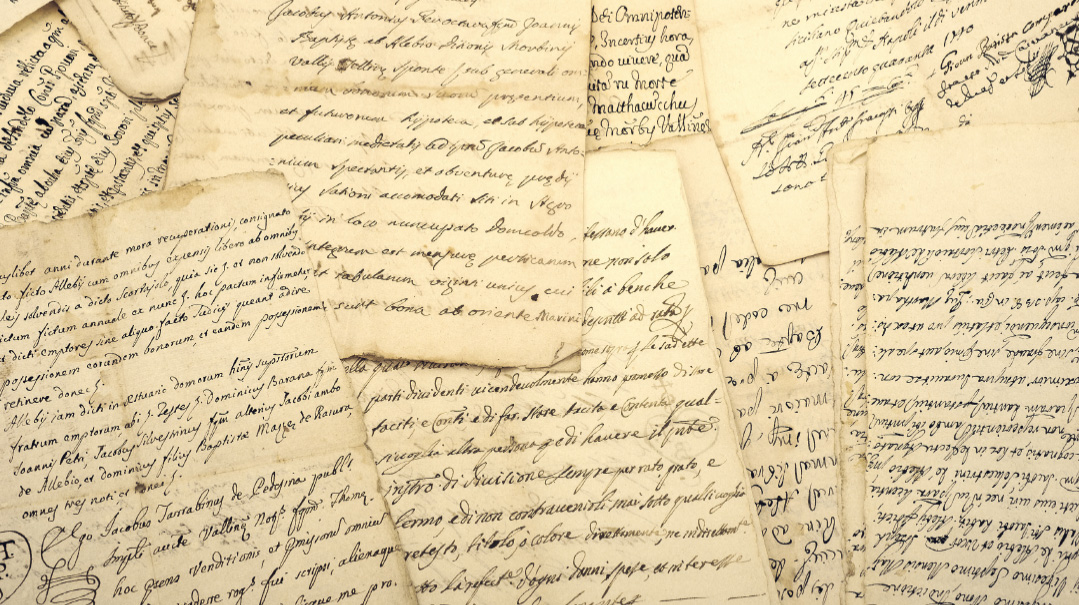

As I sorted through these books, I realized I was touching history. Among the collection was one book from the 1700s. Not only had someone written personal notes in the margins while learning, but it had the stamp of a yeshivah, as well as a stamp from the Nazi archives.

From all these clues, I imagined this book’s trajectory: First, it was brought to a yeshivah and surrounded by the beautiful cacophony of men learning. Then came the menacing sound of boots, and the book was grabbed, thrown unceremoniously on a pile, stamped, stored away, and forgotten. A few years passed until, finally, the rumbling of tanks ushered in the sweet sounds of liberation. The book was picked up, brushed off, and shipped to a friendlier, safer environment. Finally, it ended up in my hands, a young woman with a Bais Yaakov education, a continuation of the chain that our enemies tried and failed to break.

I get chills every time I relive that memory. There I was, with a degree in history, trying to figure out what to do with my life, and suddenly there was no question about my future: I needed to work in a library with Jewish books, and to delve into the forgotten stories of our nation’s past.

Detective Work

I was able to earn a master’s in Jewish studies from NYU while simultaneously getting my library degree from Long Island University, with a certification in rare books and manuscripts. As I was nearing graduation, I attended a life-changing workshop held at the University of Pennsylvania. It focused on “paratexts” — in old books, this refers to texts outside of the main text, such as title pages, haskamos, annotations, bindings, and any stamps that might tell you about where the book has traveled.

I was mesmerized. It was like being a detective, and by uncovering clues I could trace a piece of Jewish history. While I was there, I met the Curator of Judaica Collections at the University of Pennsylvania, and he suggested I apply for a position there, which ended up becoming my first official librarian job.

After a couple of years, Hashgachah led me to a new position at Columbia University. Even though Columbia has been collecting Judaica since its founding in 1754, there had never been a Jewish Studies librarian until 2008, when a generous endowment was given to establish the Norman E. Alexander Librarian for Jewish Studies, a position I now hold.

Illuminating Lives

As part of my job, I regularly give classes with the materials from Columbia’s collection. You can’t imagine the thrill of seeing a student touch a manuscript that’s a thousand years old and in wonderful condition. As they turn the pages of these books, they see the classic Jewish texts that we still read today, and often, handwriting in the margins that illuminates a flash of a life — the name of a Jew who learned this sefer hundreds of years before, or perhaps a thought on a particular devar Torah.

There’s so much we can learn from books, much more than just what’s printed on the page. Because paper was expensive and books were bequeathed from generation to generation, families would record all kinds of information in them.

Interspersed between the texts of one book I found were narratives of the family who had owned the book. It included more than 100 years of births, marriages, and deaths within a particular family. In another section of the book, someone recorded details about multiple earthquakes in the city, detailing the exact hour when the ground shook — including once during Yom Tov davening in shul. This person unknowingly created a historical record of earthquakes that we’re now reading about centuries later.

We have an archive from a shul in Mantua, Italy, that contains multiple seating charts for davening. Even then, seating was a serious issue! One text from Germany, written in the Middle Ages, documents the Purim shtick that was performed over the years.

It’s so exciting when we find a clue that links a book to its original owner. Our modern-day detective work is sometimes made easier by the oppressive censorship of Hebrew books. In Italy, in the 16th and 17th centuries, the Christian censors wrote down their names, as well as when and where they reviewed the books. That’s how we might find out, for example, that a particular book was owned by a Jew in Mantua, Italy in 1597 (and censored by Domenico Irosolomitano).

Book shop

Another aspect of my job is acquiring new books for our collection. The books we purchase run anywhere from a few hundred dollars to the tens of thousands. I always try to look at a physical copy of the book before purchasing it because it can give me clues about its origins. We don’t want to inadvertently buy a book that was stolen or suspiciously acquired. We unfortunately deal with these kinds of issues in my field.

In fact, as president of the Association of Jewish Libraries, I’m currently working with colleagues on an initiative to write a guidance document for librarians, collectors, and sellers who are dealing with provenance issues relating to Jewish material.

Along the journey

In addition to working at the library, I codirect a digital project with three professors of Jewish Studies called, Footprints: Jewish Books through Time and Place.

The goal of Footprints is to track the history and movement of printed Jewish books, starting with the inception of Hebrew type in the 15th century until the 1800s. We ask: What was this book’s journey? Who were the people who interacted with it, and under which circumstances? We currently have more than 19,000 records relating to these books, and we’re constantly growing.

“Why do you need old books anyway?” my nephew once asked me. It was right around Pesach, so I pulled down a few Haggadahs from my shelf. Every year I try to buy a copy of an old Haggadah. There are facsimiles of manuscripts and old printings that are relatively cheap, and they’re amazing to see. I have examples from Prague, Barcelona, and Germany. And it’s the exact same text as we have today, just some of the piyutim at the end are different.

I showed my nephew one Haggadah and said, “Look at this old book. Do you see how it’s mostly the same as the one you’re using?” It’s so powerful to see how our tradition has remained intact throughout our long galus.

“You don’t have to be interested in history to enjoy old books,” I told him. “Tell me what you’re interested in, and I’ll show you where in history you can find out more about it.”

One thing on my bucket list:

There’s a handwritten Haggadah called the Darmstadt Haggadah, which I’d love to turn the pages of. It was written around 1430, probably for a woman (since there are illustrations of women holding books throughout the manuscript). It is currently located in Germany.

If you could be any season, which one would you be?

Fall. I love transitions. I like moving from one thing to another.

Early bird or a night owl?

Very much an early bird. I often wake up with the sun.

If you could have dinner with anyone from history, who would it be?

Estelina Conat, the first female printer. She lived in Mantua and printed alongside her husband, Abraham, in the 1470s. She was one of the first printers of Hebrew books.

(Originally featured in Family First, Issue 855)

Oops! We could not locate your form.