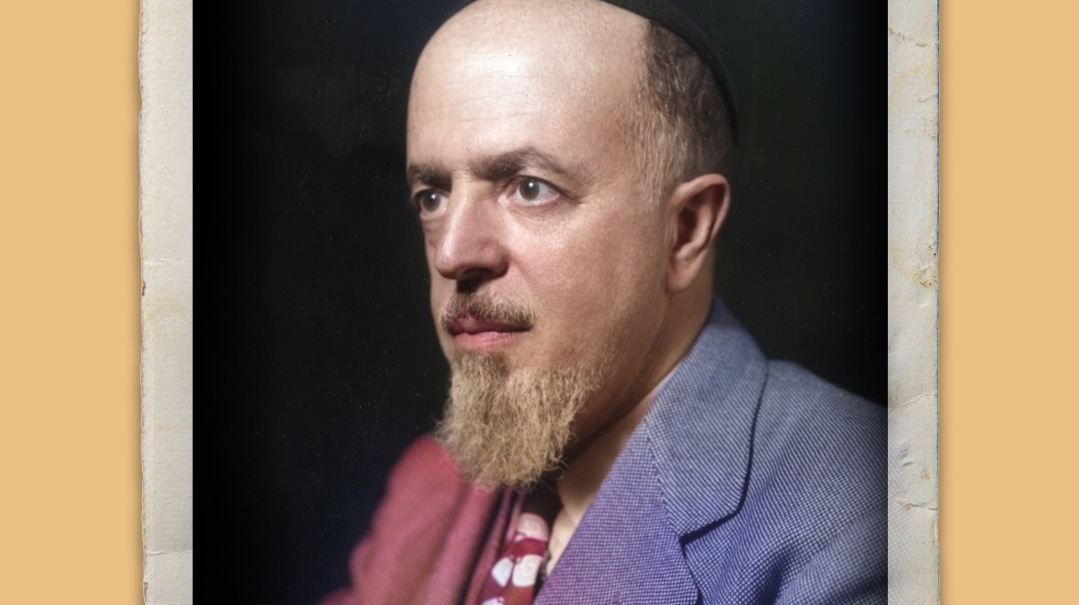

Man of Action: The Life & Times of Rabbi Leo Jung

The life & times of Rabbi Dr. Leo Jung

Photos: American Orthodox Archives of Agudath Israel, Yeshiva University Archives, JDC Archives, Jung Family, Anshei Chomer V'Tzurah, Feivel Schneider, DMS Yeshiva Archives, Artscroll, Etra Family, Chabad Archives, Tova Wolfson Photography, Jewish Women's Archive, University of South Carolina's Moving Image Research Collections, Harvard University Judaica Collection

Ahistory of the Jewish people lacking adequate recognition of the rabbis’ achievements would be as meaningless as one of the United States that had no reference to Washington or Jefferson; or of the Atomic Age that ignored Einstein, Planck, or Fermi…. There is no “typical rabbi” anywhere. The halachah does create recurrent personalities. Its genuine disciples, upheld by a pervading sense of responsibility, are learned, pious, upright, and kindly. But they differ in method and attitude; their particular emphases reveal the social, spiritual, or intellectual milieu in which the accidents of history have placed them and which accounts not only for reaction to special problems or challenges but for some singular excellence.

— Rabbi Dr. Leo Jung; Preface to Men of the Spirit; Volume 8 of The Jewish Library series

With this preface, Rabbi Leo Jung — far from a “typical rabbi” himself — could have been describing his own achievements and life experiences. The “accidents of history” that set the backdrop of his own long life placed him at the center of almost every religious event, endeavor, and initiative of the tumultuous 20th century. His work spanned continents and eras, oversaw destruction of the old and rebuilding of the new. And his ceaseless activism rejuvenated the diverse world of traditional Judaism that struggled to survive and flourish throughout the many decades of his public service.

As someone who regularly peruses archives, libraries, and used book shops, I am constantly eager to learn about new people, places, and unique stories. Yet it was on a late 2019 visit to the American Orthodox Archives of Agudath Israel that I learned of a personality whose story I’d long neglected. My close friend and mentor, the long-time devoted Agudah archivist Rabbi Moshe Kolodny, got into a discussion about the “lost heroes” of early American Orthodoxy — those who fought the battles that set the stage for the metamorphic growth of Torah Jewry in America in the post-war era. “Have you ever seen the papers of Rabbi Leo Jung?” Rabbi Kolodny asked. “He was one of the founders of Agudath Israel in America in the early 1920s and represented the movement at the first Knessiah Gedolah in Vienna in 1923.”

He then laid out three boxes on the table in front of me. As I began to peruse the contents, I was astounded by what I saw. This was an American rabbi who regularly corresponded with the Chofetz Chaim, Rav Chaim Ozer Grodzenski, Rav Aharon Kotler, Rav Yosef Chaim Sonnenfeld, Rav Yechiel Yaakov Weinberg, Rav Shlomo Zalman Auerbach, Rav Yosef Eliyahu Henkin, Rav Moshe Feinstein, the Lubavitcher Rebbe, and many other gedolei Yisrael. Secular icons Jacob Schiff, Eleanor Roosevelt, and Albert Einstein were his acquaintances as well. Even more impressive were the long lists of rabbanim he supported under the aegis of his lifesaving Rabbinic Assistance Fund, which would send out funds before Yom Tov to hundreds of struggling Torah scholars throughout the world.

There were also ledgers from Rabbi Jung’s annual Chanukah appeal for the yeshivos of Israel, detailing the distribution of thousands of dollars to nearly every single yeshivah in Israel for decades. Thanks to his vital role on the Jewish Welfare Board Chaplaincy Commission, the archives also contained hundreds of letters from Jewish-American soldiers who wrote to him with various requests and halachic questions during World War II.

The number of organizations, institutions, and initiatives with which he was directly involved and often led is so staggering that it boggles the mind. A far from exhaustive list would include his rabbinical positions in Cleveland and New York, his publication of multiple volumes of important books on a variety of Torah topics and Jewish thought, promotion of Shabbos observance and lobbying for the employment of Shabbos observers, building and funding mikvaos, building kashrus infrastructure, taking a leadership position in the OU and building its rabbinical council, public activism and leadership within Agudas Yisrael, Poalei Agudas Yisrael, Young Israel, Torah Umesorah, Bais Yaakov, and the Joint Distribution Committee, fundraising for Torah scholars and Torah institutions in Europe, Palestine (later Israel), North Africa, and the United States, and spearheading the Rabbi SR Hirsch Society to translate and publish the works of Rav Hirsch and other German rabbis. He also taught Jewish Philosophy at Yeshiva University for many years. When the Lubavitcher Rebbe (the Rayatz) arrived in the United States, Rabbi Jung invited him to his congregation in Manhattan, the Jewish Center, and later played a large part in establishing the Rayatz’s Chabad institutions and infrastructure in the country. And the list can go on.

I knew that much ink has been spilled analyzing Rabbi Jung’s role as a fighter for what he uniquely termed “Torah-true values.” I’d read many essays detailing his role in building the Jewish Center and his courage in engaging in polemics with his nemesis Mordecai Kaplan, as well as his efforts to bolster the shaky ground that American Orthodoxy then stood upon.

But sitting in the archives and sifting through those boxes, I began to wonder if everything I had read previously about Rabbi Jung was just an aperitif before the entree.

As I carefully flipped through these precious documents, it became clear to me that Rabbi Jung was not just the influential rabbi of Manhattan’s Jewish Center; he was a bastion of mesirus nefesh, chesed, and hachzakas haTorah on the highest level.

That’s how I set out on a several-year effort to study the life and myriad accomplishments of Rabbi Jung.

From what I learned, his activities during the early and mid-20th century played a major role in upholding the yeshivos of Europe and Eretz Yisrael during their most difficult times. Perhaps most importantly, Rabbi Jung was a member of the trio — the others were Rabbi Dr. Leo Deutschlander and Rabbi Tuvia Horowitz — responsible for the building, expansion, and maintenance of Sarah Schenirer’s Bais Yaakov system.

How did a pulpit rabbi in Manhattan come to assume personal responsibility for an astounding number of institutions, initiatives, and causes across the globe? Where did he find the vision, passion, and drive to marshal every possible resource and connection to the preservation of authentic Jewish practice? And perhaps most curiously of all, how did he transform his congregation of well-heeled but mostly not particularly fervent or learned Jews into ardent supporters of the yeshivah world?

Oops! We could not locate your form.