Man of Action: The Life & Times of Rabbi Leo Jung

The life & times of Rabbi Dr. Leo Jung

Photos: American Orthodox Archives of Agudath Israel, Yeshiva University Archives, JDC Archives, Jung Family, Anshei Chomer V'Tzurah, Feivel Schneider, DMS Yeshiva Archives, Artscroll, Etra Family, Chabad Archives, Tova Wolfson Photography, Jewish Women's Archive, University of South Carolina's Moving Image Research Collections, Harvard University Judaica Collection

Ahistory of the Jewish people lacking adequate recognition of the rabbis’ achievements would be as meaningless as one of the United States that had no reference to Washington or Jefferson; or of the Atomic Age that ignored Einstein, Planck, or Fermi…. There is no “typical rabbi” anywhere. The halachah does create recurrent personalities. Its genuine disciples, upheld by a pervading sense of responsibility, are learned, pious, upright, and kindly. But they differ in method and attitude; their particular emphases reveal the social, spiritual, or intellectual milieu in which the accidents of history have placed them and which accounts not only for reaction to special problems or challenges but for some singular excellence.

— Rabbi Dr. Leo Jung; Preface to Men of the Spirit; Volume 8 of The Jewish Library series

With this preface, Rabbi Leo Jung — far from a “typical rabbi” himself — could have been describing his own achievements and life experiences. The “accidents of history” that set the backdrop of his own long life placed him at the center of almost every religious event, endeavor, and initiative of the tumultuous 20th century. His work spanned continents and eras, oversaw destruction of the old and rebuilding of the new. And his ceaseless activism rejuvenated the diverse world of traditional Judaism that struggled to survive and flourish throughout the many decades of his public service.

As someone who regularly peruses archives, libraries, and used book shops, I am constantly eager to learn about new people, places, and unique stories. Yet it was on a late 2019 visit to the American Orthodox Archives of Agudath Israel that I learned of a personality whose story I’d long neglected. My close friend and mentor, the long-time devoted Agudah archivist Rabbi Moshe Kolodny, got into a discussion about the “lost heroes” of early American Orthodoxy — those who fought the battles that set the stage for the metamorphic growth of Torah Jewry in America in the post-war era. “Have you ever seen the papers of Rabbi Leo Jung?” Rabbi Kolodny asked. “He was one of the founders of Agudath Israel in America in the early 1920s and represented the movement at the first Knessiah Gedolah in Vienna in 1923.”

He then laid out three boxes on the table in front of me. As I began to peruse the contents, I was astounded by what I saw. This was an American rabbi who regularly corresponded with the Chofetz Chaim, Rav Chaim Ozer Grodzenski, Rav Aharon Kotler, Rav Yosef Chaim Sonnenfeld, Rav Yechiel Yaakov Weinberg, Rav Shlomo Zalman Auerbach, Rav Yosef Eliyahu Henkin, Rav Moshe Feinstein, the Lubavitcher Rebbe, and many other gedolei Yisrael. Secular icons Jacob Schiff, Eleanor Roosevelt, and Albert Einstein were his acquaintances as well. Even more impressive were the long lists of rabbanim he supported under the aegis of his lifesaving Rabbinic Assistance Fund, which would send out funds before Yom Tov to hundreds of struggling Torah scholars throughout the world.

There were also ledgers from Rabbi Jung’s annual Chanukah appeal for the yeshivos of Israel, detailing the distribution of thousands of dollars to nearly every single yeshivah in Israel for decades. Thanks to his vital role on the Jewish Welfare Board Chaplaincy Commission, the archives also contained hundreds of letters from Jewish-American soldiers who wrote to him with various requests and halachic questions during World War II.

The number of organizations, institutions, and initiatives with which he was directly involved and often led is so staggering that it boggles the mind. A far from exhaustive list would include his rabbinical positions in Cleveland and New York, his publication of multiple volumes of important books on a variety of Torah topics and Jewish thought, promotion of Shabbos observance and lobbying for the employment of Shabbos observers, building and funding mikvaos, building kashrus infrastructure, taking a leadership position in the OU and building its rabbinical council, public activism and leadership within Agudas Yisrael, Poalei Agudas Yisrael, Young Israel, Torah Umesorah, Bais Yaakov, and the Joint Distribution Committee, fundraising for Torah scholars and Torah institutions in Europe, Palestine (later Israel), North Africa, and the United States, and spearheading the Rabbi SR Hirsch Society to translate and publish the works of Rav Hirsch and other German rabbis. He also taught Jewish Philosophy at Yeshiva University for many years. When the Lubavitcher Rebbe (the Rayatz) arrived in the United States, Rabbi Jung invited him to his congregation in Manhattan, the Jewish Center, and later played a large part in establishing the Rayatz’s Chabad institutions and infrastructure in the country. And the list can go on.

I knew that much ink has been spilled analyzing Rabbi Jung’s role as a fighter for what he uniquely termed “Torah-true values.” I’d read many essays detailing his role in building the Jewish Center and his courage in engaging in polemics with his nemesis Mordecai Kaplan, as well as his efforts to bolster the shaky ground that American Orthodoxy then stood upon.

But sitting in the archives and sifting through those boxes, I began to wonder if everything I had read previously about Rabbi Jung was just an aperitif before the entree.

As I carefully flipped through these precious documents, it became clear to me that Rabbi Jung was not just the influential rabbi of Manhattan’s Jewish Center; he was a bastion of mesirus nefesh, chesed, and hachzakas haTorah on the highest level.

That’s how I set out on a several-year effort to study the life and myriad accomplishments of Rabbi Jung.

From what I learned, his activities during the early and mid-20th century played a major role in upholding the yeshivos of Europe and Eretz Yisrael during their most difficult times. Perhaps most importantly, Rabbi Jung was a member of the trio — the others were Rabbi Dr. Leo Deutschlander and Rabbi Tuvia Horowitz — responsible for the building, expansion, and maintenance of Sarah Schenirer’s Bais Yaakov system.

How did a pulpit rabbi in Manhattan come to assume personal responsibility for an astounding number of institutions, initiatives, and causes across the globe? Where did he find the vision, passion, and drive to marshal every possible resource and connection to the preservation of authentic Jewish practice? And perhaps most curiously of all, how did he transform his congregation of well-heeled but mostly not particularly fervent or learned Jews into ardent supporters of the yeshivah world?

Ungarisch-Brod

Raised Among Giants

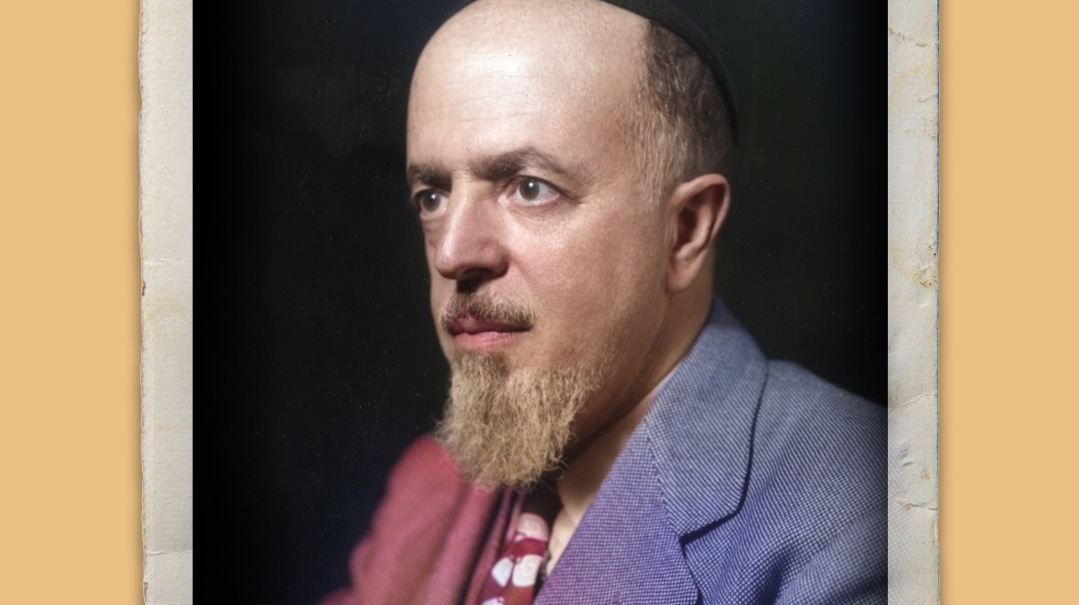

Eliyahu (Leo) Jung was born on June 20, 1892, in the Carpathian city of Ungarisch-Brod (district of Moravia), which was then part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. His father, Rabbi Meir Tzvi Jung, was the local rav and was well known in the region and beyond. He was a student of the great Hungarian Torah leaders of the 19th century, including Rav Moshe Schick (Maharam Schick), Rav Simcha Bunim Sofer (the Shevet Sofer), Rav Shmuel Ehrenfeld (the Chassan Sofer), and Rav Yitzchak Glick (the Gaon of Tolacva). He received semichah from Rav Shlomo Zalman Spitzer, the prominent rav of the Schiffshul in Vienna. Thus, Leo’s childhood environment was deeply ensconced in the Oberland atmosphere associated with the Chasam Sofer.

Following his extensive yeshivah studies, Rabbi Meir Tzvi Jung embraced a doctrine that combined extensive Torah knowledge with secular studies. Hardly the first to follow this doctrine, he followed a path blazed by Rav Yaakov Ettlinger (the Aruch La’ner) as well as the Torah Im Derech Eretz ethos of Rav Samson Raphael Hirsch, earning a doctorate in philosophy after studies in the universities of Marburg and Heidelberg before earning a doctorate in Leipzig for his thesis on Pirkei Avos.

In 1886, Rabbi Meir Tzvi was hired to his first rabbinic position in Mannheim, Germany, where he married Esther (Ernestine) Silbermann. His name spread across the region as a staunch warrior for traditional Orthodoxy and he received the call in 1891 to the ancient and famous town of Ungarisch-Brod, which had established its Jewish community 600 years prior.

Rabbi Jung’s tenure in Ungarisch-Brod was an important turning point in his rabbinic career. Ungarisch Brod was one of about 20 autonomous Jewish communities in the old Austro-Hungarian Empire with an administration of its own, a Jewish mayor, Jewish police, a Jewish hospital, and a Jewish elementary school.

When Rabbi Meir Zvi took his post, the Reform Movement was at the height of its influence, and Jewish life was reeling from unprecedented assimilation. With German Jewry on the brink of religious extinction, Austro-Hungarian Jewry replaced it as the largest German-speaking Jewish community in Europe. In order to prevent the type of mass assimilation that plagued Germany’s Jews, Rabbi Meir Tzvi Jung set out to revolutionize the educational system in the region, hoping to attract local children away from the government schools to his Hirschian-style high school, which offered both high level Torah learning and top-notch secular studies.

Rabbi Jung saw so much success in this new endeavor that he attracted the attention of educators across Europe who wished to open similar schools. In 1907, he was invited to Krakow, where communal leaders hoped he could replicate his success in Ungarisch-Brod and attract the thousands of Jewish children who were then studying in Polish high schools, where they stood little chance of remaining attached to their roots.

But even with strong demand from local families, support for the high school dissipated as various groups in Krakow began to protest the endeavor. While chassidic groups assailed Rabbi Jung for breaking with their long-held traditions, the assimilationist groups worried that his success would hurt their own schools. Strong pressure from both sides caused the school to close down, just eight weeks after its opening.

While the Krakow school was perhaps a bit premature for its time, cities like Lemberg (Lvov) and Storszynet took their cue from Rabbi Jung and formed similar schools. Nearly two decades later, when Bais Yaakov was popularized in Krakow utilizing comparable educational methods, Rabbi Jung (who had by then passed away) received apologies from some of the groups posthumously in the form of a plaque erected in his memory by the Rebbes of Belz and Premszyl at the Bais Yaakov Seminary in Krakow.

Though Krakow may not have been ready for Rabbi Jung’s pioneering approach, other communities perked their ears. The noise created by Rabbi Jung’s bold endeavors was heard in London by Sir Samuel Montagu (later called Lord Swaythling), who headed the Federation of Synagogues, a group of approximately 50 Eastern-European congregations that sought higher standards than the Westernized Orthodoxy of the United Synagogue and Chief Rabbi Hermann Adler.

They offered Rabbi Jung the position of “Chief Minister” of the Federation of Synagogues. Jung was a natural fit for the position, and so he bid farewell to his community and headed for England. (Henceforth he’d be known as Minister Jung, because Chief Rabbi Adler had made a decision to reject any semichah that was received outside his purview, in just one example of the many stark differences between Eastern and Western Orthodoxy.)

Galanta

The Dushinsky Link

Leo Jung graduated his father’s high school in Ungarisch-Brod at the age of 17. He was then sent to the yeshivah in Eperjes (Presov), Slovakia, where his maternal grandparents resided, and exceled in his studies. While his grandfather Rabbi Yaakov Silbermann headed a yeshivah for younger students, he attended the post-high school yeshivah of Rabbi N. B. Fischer, whom Rabbi Jung would later recall for his saintliness and incredible dedication to his students.

The chassidic atmosphere that permeated Presov required a period of adjustment, but before long, young Leo became acquainted with the fervent style of davening and was extremely impressed by the piousness and genuine devotion of the locals, especially the way they treated the yeshivah students with reverence and warmth.

After a few months, Rabbi Jung transfered to a yeshivah in a small town outside Pressburg called Galanta. The main attraction there was the rosh yeshivah, Rav Yosef Tzvi Dushinsky, whom Rabbi Jung described with awe in his memoirs:

At the yeshivah, Rav Dushinsky started the morning shiur with interpretations from a passage from Chumash, with a disquisition on a paragraph in ethical literature (notably the Chovos Halvavos), and would spend the rest of the morning expounding a page of the Talmud. He paid special attention to every word of the classic commentary, Rashi. We learned from him how to read with complete concentration every utterance of that sage and how to anticipate the problem later scholars broached by reading between the lines of Rashi’s text. The Rav included the early commentaries in his lectures, but with amazing learning found proper answers to difficult textual problems in stray references in other parts of the Talmud. He eschewed artificial expositions (pilpul) and insisted on the student’s appreciation of principle and precedent as the timeless method in the history of Jewish law. He was austere, almost hermit-like, in his private life. At two o’clock in the morning the light in his study was still shining, but at six o’clock he was ready for the morning services.

Rav Dushinsky was the rabbi of Galanta and headed one of the most prestigious yeshivos in the Austro-Hungarian Empire. A talmid of the Shevet Sofer, Rav Dushinsky was a leading rabbi in Oberland prior to his move to Eretz Yisrael. On a later trip to Palestine in 1933, Rabbi Jung would get an opportunity to renew his relationship with Rav Dushinsky, who succeeded Rav Yosef Chaim Sonnenfeld as the leader of the Eidah Hachareidis after the latter passed away in 1932. Rabbi Jung would ultimately become a lifeline for the Dushinsky mosdos, helping to build and maintain Rav Dushinsky’s flagship yeshivah, Bais Yosef Tzvi, in Yerushalayim.

In 1911, now a budding Torah scholar, Rabbi Jung made plans to take his learning to even greater heights at the famed yeshivah in Unsdorf under Rav Shmuel Rosenberg, but destiny got in his way when he contracted a rude form of food poisoning in Galanta. After being sick for several months at home, Eliyahu Jung made a decision that would change the course of Jewish History, agreeing with his mother’s proposal that he enroll in the famed Hildesheimer Rabbinerseminar in Berlin.

Berlin

Role Model for Life

It was there that Rabbi Jung became entranced by Rav Dovid Tzvi Hoffman, who had succeeded Rav Ezriel Hildesheimer as rector following his passing in 1899. In Rabbi Hoffman, Rabbi Jung saw an embodiment of the same Torah im derech eretz qualities and traditions he had been raised upon.

Rabbi Dr. Hoffman (1843–1921) was a student of Maharam Schick and Rav Ezriel Hildesheimer. He was universally recognized for his encyclopedic Torah knowledge and halachic erudition and was recognized as one of the leading poskim in Western Europe at the turn of the century. This erudite Torah scholar also held a doctorate from the University of Tubingen, and was well versed in classical languages, philosophy, and literature. He utilized his scientific and academic background to confront the heresy of his day, primarily Bible criticism.

A stern and exacting educator, Rabbi Dr. Hoffman demanded hard work from his students, yet was compassionate, kindly, and attuned to their needs. His mastery of all of halachah, coupled with his incisive depth in the entirety of Shas, was matched by his willingness to confront the academic world on their own terms, utilizing their own methodologies. He inspired awe and reverence among his talmidim who were amazed at his scholarship and clarity, and yet witnessed his piety while observing the intensity of his prayer. The young Leo Jung was deeply impacted by his years as Rabbi Hoffman’s student.

In 1912, when Agudath Israel was founded to bring together the various, diverse strands of European Orthodoxy, Rav Dovid Tzvi was appointed as one of the members of the original Moetzes Gedolei HaTorah. Rabbi Jung’s father also joined the nascent movement, serving as the honorary Agudah chairman in England.

London

Internment and Freedom

During the summer of 1914, his mother took ill, and Rabbi Jung traveled to London to visit her. When World War I broke out a few weeks later, Rabbi Jung was forced to remain.

He was far from the only “refugee” in London during that time. Rav Avraham Yitzchok Hakohen Kook, then chief rabbi of Jaffa, had traveled to Europe that summer for a conference of Agudath Israel and found himself in Germany when hostilities broke out. Seeing that there was no way for him to return home, he fled to London by way of Switzerland, and spent the war years as the leader of the Machzekei Hadath community there.

Rabbi Jung would become one of three students Rav Kook taught in his “yeshivah,” which was hosted at the Spitalfields Great Synagogue. Rav Kook was the first of several to grant Rabbi Jung semichah.

At the same time, Rabbi Jung and his brother Moshe (Moses) enrolled in the prestigious Cambridge University. One day toward the end of the war, they were suddenly snatched away from the campus by local authorities and placed in custody on the outskirts of London in Alexandra Palace, an internment camp that the British government had set up for enemy citizens of military age. For nearly a year they remained at the camp with thousands of other German and Austro-Hungarian nationals. Local dignitaries and politicians pleaded their case to no avail.

With their father unwell and their mother recently deceased, it was their younger sister Bertha who would be their savior. She regularly came to visit, laden with packages of kosher food, sustaining them during those difficult months. Bertha would later marry Rabbi Yisroel Ehrentrau, rav of Munich. Their son is the renowned Torah scholar, Dayan Chanoch Ehrentrau, shlita of London.

My exhaustive research in the records of the House of Commons revealed that it was John Frederick Peel Rawlinson, the Cambridge University Member of Parliament, who pleaded the Jung brothers’ case before Home Secretary Edward Shortt, eventually winning their freedom in 1919 after several denials.

Rabbi Jung utilized his years in London for communal activity as well. He served as director of the Sinai League, an organization founded by his father to promote traditional Jewish values among the young Eastern European immigrants. He was also the editor of the organization’s journal, The Sinaist and joined his father, Rav Kook, and others in contributing many important and thought-provoking articles.

Cleveland

Shaky Foundations

In 1919, Knesset Israel, a shul in Cleveland, Ohio, offered the position of rabbi to Rabbi Meir Tzvi Jung, who declined and offered to send his son in his stead. The younger Rabbi Jung had already received offers from congregations in Cape Town, Leeds, and Shanghai, but felt that the Cleveland opportunity was worth exploring and traveled to America to audition for the position. Early the following year he returned to begin a rabbinic career that would last more than 60 years.

The state of Judaism that Rabbi Jung was to encounter in America was perhaps even bleaker than that of England, which at least had a fairly organized and more established Orthodoxy and lacked a powerful Reform movement to contend with.

One of the most poignant examples of the tragic trajectory of American Orthodoxy comes via author Hutchins Hapgood, who chronicled the hypocrisy of immigrant Jews attending the Yiddish theater on Friday night:

The Orthodox Jews who go to the theater on Friday night, the beginning of the Sabbath, are commonly somewhat ashamed of themselves and try to quiet their consciences by a vociferous condemnation of the actions on the stage. The actor, who through the exigencies of his role, is compelled to appear on Friday night with a cigar in his mouth, is frequently greeted with hisses and strenuous cries of “shame, shame, smoke on the Sabbath!” from the proletarian hypocrites in the gallery.

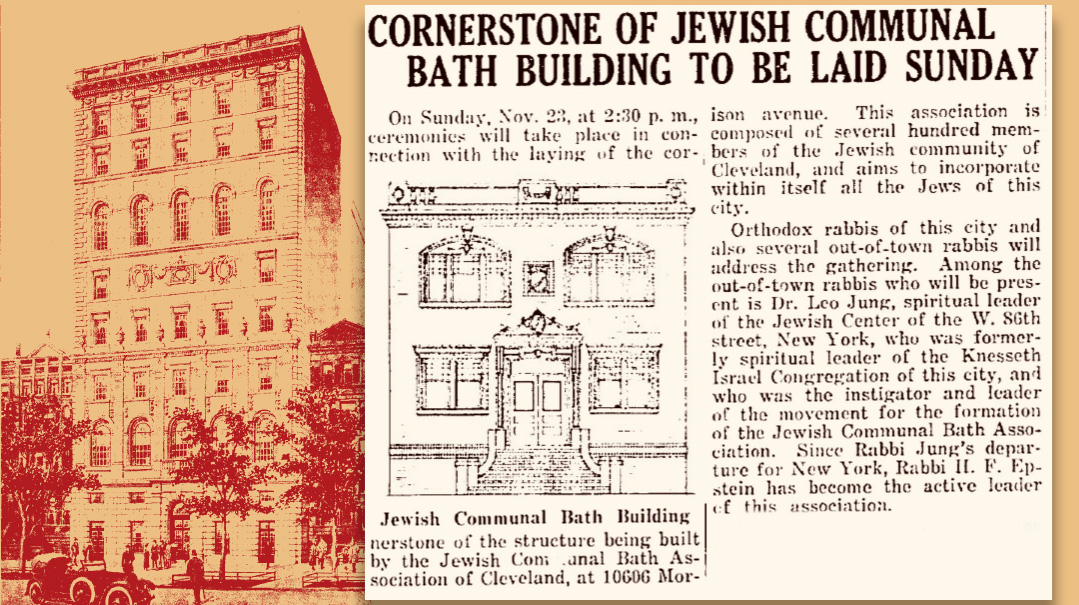

In Cleveland, Rabbi Jung immediately faced an uphill battle to bolster the status of Orthodoxy. When he invited a prospective bride to meet and discuss the laws of family purity she exclaimed with astonishment, “You believe in those things??” When he saw the awful state of the seldom-used mikveh, he implored its owner to make improvements. When his pleas were ignored, Rabbi Jung mounted a campaign to raise a thousand dollars to build a new one, the first of 15 mikvaos that Rabbi Jung built across the world.

(In 1933, the working-class community of East New York approached Rabbi Jung for help financing a badly needed new mikveh. Rabbi Jung had just returned from a trip to Palestine and had more than 500 feet of film of video from the trip. He immediately organized a screening of the film to raise funds for the East New York mikveh.)

Rabbi Jung’s two-year tenure in Cleveland was punctuated by several trips to England and Germany. In 1920, he returned back to Berlin to complete his semichah with Rav Dovid Tzvi Hoffman at the Rabbinerseminar and in 1921, to London to successfully defend his dissertation. It was on his 1921 trip to Europe that his father suddenly passed away. It was also during that trip that he visited his sister Bertha who was in Switzerland, recuperating from a bout of pneumonia. There he was introduced to Irma Rothschild, a young woman from a prestigious Swiss family. In his memoirs, Rabbi Jung described their initial meeting:

At Stansstad, on Lake Lucerne, I met Irma Rothschild who had volunteered to run a camp for refugee children. I saw her, a Kitzur Shulchan Aruch in her hand, lecturing to her charges. Next day we climbed up Pilatus together and in the evening I proposed to her. Her response, finally, was encouraging.

The Rothschild family was renowned in Switzerland for their uncompromising commitment to Torah life as well as their hospitality and chesed. One needs to look no further than Rabbi Jung’s description of his wife’s grandfather and the many generations of Torah-fearing Jews that the family continues to produce to see how this union was truly a “match made in heaven”:

Her grandfather, Jacques Lang, legendary in religious loyalty, established a department store, closed on the Sabbath and on all Yamim Tovim (Jewish Holidays), and left a house and legacy for the establishment of the first Yeshivah in Switzerland. His dreams were realized two generations later, when the Torah Academies of Montreux and Lucerne rose to bless the land and Jewish communities all over Europe and his grandchildren went to yeshivos and remained within the happy circle — tomcheha me’ushar — of Torah supporters, uncompromising Torah-true Jews.

Rabbi Jung with his wife and three of his four daughters Erna, Rosalie and Julie in the early 1930s

New York

The Mordecai Kaplan Saga

Back in the United States, Rabbi Jung realized that without quick and decisive action, an entire generation of Jewish immigrants was bound to be lost to Judaism. “We are not ready to deliver a eulogy or write an obituary for American Orthodoxy,” he declared, and harnessing his staunch Torah background, his classic education, and seemingly endless energy, he got to work.

While his first bold moves were made in London and Cleveland, it was in the most populated Jewish city on the planet where Rabbi Jung was to make history.

The turn of the century saw the development of the Upper West Side of Manhattan along with a steady stream of Jewish migration uptown. Several laymen established a new congregation in 1918 on West 86th Street to meet the community’s needs. A young rabbi named Mordecai Kaplan was hired as leader. The son of a dayan on the Beth Din of Rav Yaakov Yosef, the Rav Hakollel, he was a graduate and teacher in the Jewish Theological Seminary (which was still nominally Orthodox at the time). Kaplan pioneered the idea of the Jewish Center, a synagogue that would include cultural, social, recreational, and educational programs in addition to prayer, in the hopes it would appeal to the next generation.

But that was the least of Kaplan’s ideas and innovations. As his radical views evolved, he began to mount frontal attacks on traditional Judaism. He penned an article calling for “A Program for the Reconstruction of Judaism.” The ensuing controversy drew strenuous criticism, particularly a series of articles penned by a newly arrived rabbi in Cleveland named Leo Jung.

Rabbi Jung condemned Kaplan’s positions on Judaism, rightfully accusing Kaplan of “downright apikorsis” and of “sweeping away the foundation of Jewish tradition…” Eventually the Jewish Center laity and Kaplan parted ways, with the latter resigning in 1921 and taking half the Shul’s members along with him. (Kaplan’s 1945 publication of his Reconstructionist Sabbath Prayer Book was so full of heresy, that it led to one of the only known uses of the Cherem in modern times, with the Agudath Harabbonim excommunicating him in response and burning his novel Prayer Book.)

In a historical twist of irony, the Jewish Center filled the empty position by hiring none other than Rabbi Leo Jung. If there was ever a perfect match between a rabbi and his congregation, it was that of Rabbi Leo Jung and the Jewish Center. The congregants of the Jewish Center were, for the most part, what Rabbi Jung deemed “higher middle class” or wealthy and ran in social circles that included the upper echelon of Jewish high society. On the surface they seemed like perfect candidates to join the growing American Reform movement and not “dying” Orthodoxy. But from inside the walls of the ten-story Jewish Center, a synagogue that was regularly referred to as a “Rich Man’s Club,” that was not to be the case.

Rabbi Jung believed that American Jewry had not rejected Orthodoxy; rather it lacked an exposure to the “Torah-true Judaism” (Torah im derech eretz) that he had been reared upon. From the pulpit he stressed decorum, adherence to the Shulchan Aruch, and a focus on learning, combining both Torah and Western knowledge to deliver meaningful talks that would resonate with both generations of congregants.

Rabbi Jung keenly observed that in America, suffrage had created households where women could be free of full-time housekeeping and child-rearing. Together with his wife, he made women a focus of the Jewish Center community, encouraging them to take advantage of their prosperity to help others, as well as to improve mitzvah observance in the home. The Jungs saw the American idea of “free time” as dangerous and helped build sisterhoods at both the Jewish Center and OU to provide opportunities for women to fill their days with good work.

The respect that Rabbi Jung earned among his congregants was shared by Orthodox Jews across America. OU and Torah Umesorah President Mr. Moses Feuerstein recalled meeting Rabbi Jung for the first time in the mid 1920s when he visited Boston together with Rabbi Herbert Goldstein as part of an OU delegation exploring the establishment of kosher facilities for observant students at Harvard. His father, Samuel Feuerstein, was a renowned Orthodox businessman and philanthropist involved in many important causes. The younger Feuerstein recalled the respect that his father (and so many others) shared for Rabbi Jung:

Orthodoxy was then in a period of decline and disintegration. The few Jews who remained Orthodox were lonely outposts battling valiantly to raise the prestige and stature of Orthodoxy. In discussing these problems, my father and Rabbi Jung found in each other kindred souls.

Recently a distinguished senior member of the Brookline community, in discussing the sad passing of Rabbi Jung, reminisced about his escape from Germany and his experiences in America. In 1935, he said, after losing his first job in the United States because he was shomer Shabbat, he went to Rabbi Jung. He feared that he would lose his Yiddishkeit if he stayed in New York — a situation he saw happening all too frequently among his friends. He told the Rabbi that he would be willing to go to any smaller community that Rabbi Jung might recommend.

Without a moment’s hesitation, Rabbi Jung said, “Go to Malden. Tell my friend Sam Feuerstein that I sent you, and he will give you a job.” The young man was hesitant and worried. He wrote to my father, telling him what Rabbi Jung had suggested, but there was no reply.

The young man went to Rabbi Jung again. The Rabbi patiently responded, “Just go to Malden and you will be provided with a job.” When the applicant arrived in Malden, my father replied that employment would be impossible. He had just laid off 80 people, and the union would probably go on strike if an outsider were hired. For a few moments there was silence. Then my father murmured to himself, “How can I let down my good friend Rabbi Jung?” He picked up the telephone, called the superintendent, and told him to find a job for the young man.

My father felt that business responsibilities precluded his spending as much time with communal matters as he should. However, by providing the necessary resources for Rabbi Jung, he could realize the ideal balance between “having” and “doing.” Whenever there were special needs, be it for worthy individuals, the needy, scholars, publications, schools or yeshivot — causes which were not yet popular or which required discretion and confidentiality — in all these, there was a unity of purpose and understanding between my father and Rabbi Jung.

The friendship between the two men that began in the 1920s continued for decades to come. Rabbi Jung found in my father a devoted personal friend with whom he could share his dreams. My father always spoke of Rabbi Jung as a prince. He felt privileged and ennobled by the friendship. The warmth and affection which flowed between them was distinguished by its beauty and its spirituality.

Focus on the Future

Rabbi Jung’s passion for educating young people led to his involvement in the budding Young Israel movement, as well as the independent activities he conducted on various college campuses, where he saw young Jews leaving observance in droves. In impressing upon his congregants the importance of chinuch, he often shared a story he’d relate in the name of the British Chief Rabbi Joseph Hertz:

Dr. Hertz, chief rabbi of England, tells the story of English biologist Thomas Huxley arriving in Dublin to address a meeting of a learned society. Throwing himself into a cab, and telling the driver “Drive fast,” the driver did so. But, after a moment, Professor Huxley aroused himself from meditation on the subject of his address and said: “Do you know where you are going to?” “No, sir,” said the driver, “but I am driving fast.”

Rabbi Jung would then remind his audience that in Judaism, it wasn’t the speed that counted, but rather the direction which was important — and it must be both pointed and well thought out.

In 1928, Rabbi Jung spearheaded a pioneering literary project he entitled The Jewish Library Series. It was revolutionary in that it expressed the values, beliefs, and philosophy of traditional Judaism, making it relevant to the contemporary reader, and most importantly it was the only one of its kind to be written in English.

In the early decades of its publication, The Jewish Library was the only English-language material geared to young American Jews exploring Yiddishkeit. Two series of the Jewish Library produced 16 impressive volumes, which appeared consistently through 1980. Of particular historical importance was the final three volumes of Series One, which contained biographical profiles of leading Torah personalities from around the world. This groundbreaking collaborative effort by an international team of scholars predated the gadol biography genre that has become so popular in contemporary Jewish society. Rabbi Jung described the importance of this project in the introduction to the third volume of the trilogy:

“Within a generation — some of the great men presented here might be forgotten, a sad example of careless ingratitude. Every chapter of these volumes adds a significant nuance to the power and grace of the Jewish scene. It has been my aim to include every vital variety of rabbinic leader, from patient saint to impatient pioneer, from the Tzaddik in the Eastern lands to the Gaon in Central Europe, from the protagonist of Torah im derech eretz to the builder-up of spiritual waste-places… The resiliency of these great men, working under ceaseless emergencies, their optimism vindicated a hundred times, with an awareness, never quite absent, of evil things to come, together present unconquerable souls inspired by faith, formed by moral training, and upheld by the conviction that the Torah they learned, lived, and taught would in fullness of time ‘refine and unite human beings.’”

Rabbi Jung also met with some failures along the way. In 1923, he joined up with Rav Shraga Feivel Mendlowitz, Rabbi Herbert Goldstein, and others to form a weekly newspaper to espouse Torah-true values called Dos Yiddishe Licht. Financed in part by guarantees from Cantor Yossele Rosenblatt, the Yiddish-English weekly newspaper failed to attract enough subscribers and went out of business after a few years, bankrupting the famous chazzan in the process.

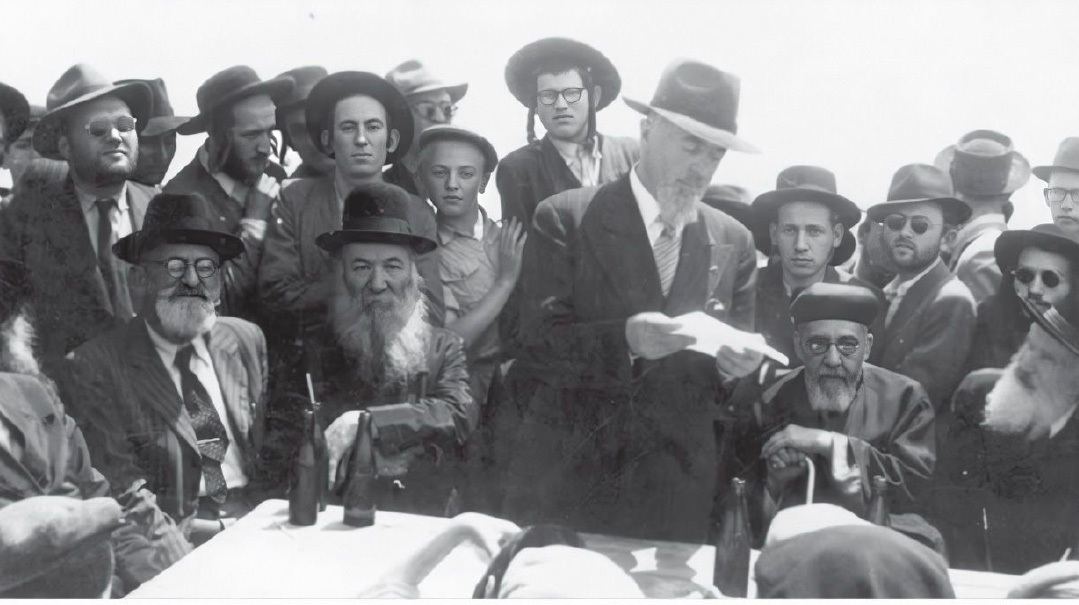

The Keren Hatorah delegation meeting with Rav Elchonon Wasserman (front right), Rav Chaim Ozer (head) at a banquet hosted in their honor

Building Bais Yaakov

One of the most important relationships Rabbi Jung forged during his years in Berlin was with Rabbi Dr. Leo Deutschlander, who stood at the helm of the Keren HaTorah fund of Agudath Israel. Like a central bank, the “Keren” raised and collected funds from communities and individuals in Western Europe, where economic conditions were far better, to be distributed to Torah institutions in those Eastern countries according to need. The Keren was also involved in the establishment and maintenance of primary Torah schools in Germany and other western countries.

In 1923, in order to mark a decade of support for the fund, Dr. Deutschlander proposed a tour of mosdos haTorah across Eastern Europe for the leading rabbis and community leaders of Western Europe. The delegation, led by Dr. Deutschlander and Rabbi Yosef Tzvi Carlebach, would visit and acquaint themselves with the conditions of the major yeshivos and chassidic institutions throughout the region. Above all, it would create an opportunity for dialogue between the Torah leaders of both East and West.

Rabbi Jung, who at the time was perhaps America’s leading “Agudist” and represented America at the first four Knessiah Gedolahs (by the 1940s his shift toward Zionism would see him move to the more labor-oriented Poalei Agudath Israel) was chosen as the American representative and joined the venerable delegation. In addition to visiting the Chofetz Chaim, Rav Chaim Ozer, and Rav Meir Shapiro, the Keren HaTorah group visited the Bais Yaakov of Frau Sarah Schenirer in Krakow. At that time, Bais Yaakov was a small yet growing movement.

The Imrei Emes was reported to have said around that time: “I have thousands of bochurim amongst my followers, but I am not sure whether there exists even for ten of them girls who are fit and willing to share their lives. What will become of our future families?” The day when Leo Deutschlander met Frau Sarah Schenirer and agreed to take charge of the development of the Beth Jacob movement was a historic one, because it provided the solution to the Gerrer Rebbe’s problem.

Here, a union was created which was to bring about the fulfillment of a great plan. Sarah Schenirer, the daughter of chassidic Jewry, entrusted the furthering of her ideals to the educationist reared in the schools of Torah im derech eretz. Leo Deutschlander, in turn, invested his heart and soul in her project, and helped grow it into a driving force.

Due to Dr. Deutschlander’s vision and efforts, the dynamic movement grew from eight schools with an enrollment of 1,130 students in 1923, to 55 schools with 7,340 students by 1926. Rabbi Jung was amazed by what he saw and later termed Deutschlander “the greatest educationist Torah-true Judaism produced in the twenties.”

Upon his return to New York, Rabbi Jung immediately formed the American Beth Jacob Committee, which he went on to chair for the next half-century. The committee’s stationary proudly displayed 131 W. 86th St. (The Jewish Center) on its masthead as its official address for decades. The committee may have had additional names on it, but for the most part, the bulk of the fundraising was done by Rabbi Jung alone, utilizing every connection he had to help the burgeoning movement. His appeals were filled with superlatives that displayed his true passion for the movement:

Last summer, in Krakow, I saw the type of Jewish girl graduating from these schools. It is a type utterly unheard of before, filled with a missionary zeal to spread Judaism among Jews, to uplift the level of individual and communal life. These young women will write their names in golden letters into the records of contemporary Israel. The House of Jacob (in the words of our sages) is the Jewish womanhood. With our women loyal to the Torah, the better half of our problem is solved. I can imagine no claim more resistless, more inspiring, more promising than that of Beth Jacob, the House of Jacob to the sons and daughters of Israel.

Rabbi Jung’s annual summer trips to visit his wife’s family in Switzerland took on new meaning as he began taking side trips to the various country sites where Bais Yaakov teachers were trained. During those visits, he helped them improve their teaching methods. Later he taught classes in Bais Yaakov schools as well as in the teacher’s seminary in Kracow. One Krakow Bais Yaakov teacher aptly summed up Rabbi Jung’s summer visit: “He brought the sunshine of happy, cheerful, and intelligent normality.”

With Polish Rabbis and Senators at the 1923 Knessiah Gedaliah in Vienna

More Than a Building

Documents from the JDC archives reveal that Rabbi Jung raised more than two thirds of the funds to build the Bais Yaakov Teachers Seminary in Krakow. Rabbi Jung recalled that a major portion of the building costs were raised in a rather unconventional fashion: He used his charm and persuasive powers to arrange an event in honor of the wife of the famed author Israel Zangwill. Among the guests were Mrs. Frieda Warburg (daughter of Jacob Schiff and married to Felix Warburg of the banking family), Mrs. Rebecca Kohut, Mrs. Cyrus Adler, and Mrs. Sue Golding. Rabbi Jung later told David Kranzler how the focus of his arguments on the movement’s behalf to these largely secular women was “the need to save poor Jewish girls from White Slavery.” In the words of Rabbi Jung, “Hashem, in His inscrutable wisdom, bestowed the zechus (merit) of that priceless achievement upon three Reform women, one Conservative, and one Orthodox.”

When the ground was broken for the landmark building in 1927, Rabbi Jung attended as an honored guest and delivered a rousing speech. Years later, Rabbi Wolf Jacobson paid tribute to Rabbi Jung when writing about the event:

While only made of brick and stone, it was much like building Yeshivas Chachmei Lublin, the symbol of the desire of the chareidim to increase their power, their aspirations to prepare the girls for their lofty task in life.

I witnessed all the stages of construction, from the groundbreaking in 1927 to its completion. I saw Dr. Deutschlander’s suffering and devotion to try and fund the expenses. And the world was so cold and indifferent. Only Rabbi Dr. Eliyahu Jung of New York was a loyal supporter and of assistance.

When the building was begun, they prepared it for use for decades ahead; but by the time it was built, it was already packed with girls from the cellar to the attic. There was so much brachah in this endeavor, as all those involved meant it solely l’Sheim Shamayim!

As Bais Yaakov enrollment swelled in the early 1930s, Rabbi Jung mounted his boldest campaign yet, utilizing speaking engagements and articles in Jewish newspapers across the country to implore American women to do their part to assist this unusual cause:

Jewish women of America will have the opportunity to “adopt” one or more of the 30,000 Jewish girls now attending the Beth Jacob Schools in Eastern Europe, says Rabbi Leo Jung in a communication to the Jewish Exponent. A campaign whose goal is the “adoption” of 10,000 girls in this country has just been launched by the American Beth Jacob Committee. The adoption program was proposed at a meeting held recently in New York City under the auspices of this committee, and 25 girls were adopted at this meeting.

Beth Jacob is the Jewish woman’s movement. It has a legitimate appeal at all times and to every woman who is conscious of her prerogatives and her responsibilities. Thirty thousand girls have rebuilt their lives through Beth Jacob. There are frantic appeals from 50,000 more.

Every day, letters written with Biblical pathos and simplicity are received by the general director, Dr. Leo Deutschlander, in Vienna, by Mrs. Sara Schenirer in Cracow and by the heads of the schools in Lithuania, Latvia, Czechoslovakia, and adjacent countries. The American Beth Jacob Committee, therefore, decided to call upon the American women, inviting them to adopt the girls in these schools.

The education of a Beth Jacob girl costs $5 per year. The committee will have at its disposal all the details of the biography of the girls to be adopted. It is expected that personal relationships will develop between the adopter and the adoptee, and as Mrs. Rebekah Kohut so beautifully puts it, “The American Jewish woman may find in Beth Jacob means for their moral regeneration, for the revival of their own Jewishness.”

This invitation goes out in the name of the girls abroad, of their parents and of the Jewish community.

Bais Yaakov students relax in front of the completed building in Krakow in 1934

The tragic deaths of both Sarah Schenirer and Leo Deutschlander in 1935 did not halt Rabbi Jung’s enthusiasm for their mission. When the war began in Europe, Rabbi Jung stood at the helm of a campaign to send packages of food and clothing to Bais Yaakov schools across Poland, while at the same time producing countless affidavits for the rescue of teachers.

In 1942, Rabbi Jung received a shocking letter from Krakow via World Beth Jacob Secretary Meir Schenkolewski and Agudah leader Moreinu Yaakov Rosenheim. The letter, signed by one Hannah Weiss, detailed her decision, and that of 92 Bais Yaakov schoolmates, to commit suicide rather than be forced into unfathomable acts by German soldiers. Acting upon Rosenheim’s request, Rabbi Jung had the letter translated into English and published in The New York Times.

The letter evoked a great emotional reaction among Jewish communities around the world, who were just beginning to learn of the unspeakable horrors unfolding in Europe. The 26th of Adar, the eighth yahrtzeit of Bais Yaakov founder Sarah Schneirer, was designated by the Keren HaTorah as a day of mourning and commemoration for the heroic martyrs, while memorial gatherings continued to be held by Jews of all stripes during the ensuing months. (While the letter was assumed to be true at the time, historians of all stripes have cast major doubts on the letter’s authenticity and the veracity of the narrative therein. Today, most see the letter as a metaphor for the suffering and sacrifice of Jewish women during the Holocaust.)

After the war, Rabbi Jung doubled down on his effort to resurrect a movement most believed would be relegated to the dustbin of history. Utilizing his leadership position within the JDC, he procured funding for the Bais Yaakov schools that were being formed in the Displaced Persons Camps in Germany. He also took a personal interest in assisting a large contingent of young women who had found refuge in Sweden under the leadership of Rabbi Wolf Jacobson.

Moreover, he took an expanded interest in funding the nascent Bais Yaakov movement in America. Rabbi Israel Tabak, who was the rabbi at Baltimore’s Shaarei Zion from 1932 until 1979, “could not recall a single occasion that Rabbi Jung turned down a request to speak at a fundraiser for Bais Yaakov of Baltimore.” Rabbi Jung also helped fund the early Bais Yaakov system and Chinuch Atzmai in Israel, funding the construction of Machon Bais Yaakov Lemorot (which for decades housed Rebbetzin Bruria David’s BJJ seminary) and traveling to the country in 1947, where he was an honored guest at its cornerstone laying.

“I remember his passionate appeals for Chinuch Atzmai,” a senior member of the Jewish Center remembered. “I’m not even sure that I knew what they did. But it was clear to all of us congregants how important it was to Rabbi Jung, so we opened our wallets and gave generously.”

Rabbi Jung speaking at the 1947 Cornerstone Laying of Machon Bais Yaakov Lemorot in Yerushalayim. Also pictured are Rav Zalman Sorotzkin, Sephardic Chief Rabbi Ben-Zion Meir Uziel and Rav Shlomo Dovid Kahana

Support Our Yeshivos

In order to properly grasp the incredible scope of Rabbi Jung’s more than 60 years of valiant work on behalf of the Torah world, it’s important to understand the state of Torah support among the American community prior to his involvement.

During the years prior to the First World War, Torah leaders sought financial assistance from Western Europe and the wealthy Jewish communities outside the Pale in Russia. Following the chaos and upheaval caused by the war, the communities in Western Europe were overwhelmed by an unprecedented humanitarian crisis and could no longer provide the same support as in the past. The once-wealthy Russian Jewish communities were now under Bolshevik control and successful factory owners and financiers saw their businesses nationalized and seized by the government.

While yeshivos such as Mir and Volozhin did send meshulachim to America in the late 19th century, they saw little success there. Their salvation came about thanks to the formation of several relief organizations with a common goal: to help Jews in Europe and Palestine who were suffering greatly in the wake of “The Great War.” Ultimately, The Central Relief Committee (CRC), founded by Eastern European rabbanim then living in America, merged with the American Jewish Relief Committee (AJRC), which had been created by members of the “Uptown’’ German-American Jewish community, who were closely aligned with the American Jewish Committee (AJC). In November 1914, the CRC and the AJRC established the Joint Distribution Committee (JDC) to coordinate their relief efforts.

The JDC is undoubtedly responsible for saving the lives of hundreds of thousands of Jews and is possibly the greatest Jewish philanthropic endeavor in all of Jewish history. The JDC sent convoys of trucks with food, clothing, and medicines to devastated Jewish communities throughout Europe and dispatched its own staff of doctors, public health experts, and social workers to this volatile region to help establish relief programs, and new health and childcare facilities. Soup kitchens were set up, hospitals rebuilt, and orphanages opened. Additionally, funds were designated for all streams of Jewish education, and the allocation toward religious education helped support a myriad of Torah study during the interwar period.

While the roshei yeshivah greatly appreciated the support provided by the Joint, there often remained an element of misunderstanding between the groups, primarily due to diverging worldviews. The majority of those who funded and administered the Joint were secular Jews, but there was mutual respect, nonetheless. Rabbi Israel Levinthal, who traveled to Europe on behalf of the Joint visited the leader of Lithuanian Jewry, Rav Chaim Ozer Grodzinski, who told him, “American Jewry has not only saved the body of Polish Jewry but it has saved the Torah in our land!”

Rabbi Israel Klavan, a leading American rabbi and later executive vice president of the RCA, recalled an incident that occurred when he accompanied Rav Yosef Dov Soloveitchik and Rav Moshe Feinstein to plead with the Joint for additional funding for yeshivos in the wake of the Yom Kippur War. Rav Soloveitchik related to the secular board the following story:

I went with my father to visit his brother, Reb Velvele (The Brisker Rav). I believe it was in Warsaw. Before I could say Jack Robinson, my father and my uncle were engaged in a deep controversy about the explanation of a difficult passage in the gemara. My uncle turned to me and said: “Go next door and bring us thegemara.”

I walked in and I saw in the bookcase something that I had never seen before, a new Shas, a new set of the gemara. I never knew that a gemara could be anything but a collection of tattered sheets. That is all we had during the whole period. Here, suddenly, I lovingly took out a gemara that was brand new. On it, it said “Matanah-meiha-Joint — a gift from the Joint to the Jews [of Poland].”

It seems the Joint had distributed newly printed sets of the Talmud to the leading rabbis of Poland. I must thank you for these two gifts before I speak to you today.

In 1926, Rabbi Jung was invited to join the JDC Cultural Committee (which dealt with religious needs in Europe) and became its chairman in 1941. It was in this role that he directed millions of dollars to mosdos haTorah throughout the world.

The role did not always come easy. Oftentimes, when the JDC was uninterested in the causes he championed, he had to turn to his trusted balabatim for assistance. Rabbi Jung is reported to have said: “The job of a rabbi is to comfort the afflicted and to afflict the comfortable.” Some saw Rabbi Jung’s constant appeals as “affliction,” but most seized the opportunities he placed before them. Rabbi Jung illustrated the latter with an anecdote:

At the first Knessiah Gedolah of Agudath Israel which took place in Vienna in the summer of 1923, I had the inestimable privilege of meeting the universally revered Chofetz Chaim. To my delight, he invited me to meet with him and I spent a whole morning in his company. He wanted to know about the state of Taharath Hamishpachah in America and when I told him about my pioneering efforts, he felt very much encouraged.

Between 1918 and 1936, I had visited Eastern Europe five times, had been shocked by the poverty, and inspired by the undeviating loyalty to Torah, of our people in these countries. What I observed of their plight developed a tension that made me impatient with the perfectly reasonable attitude of my colleagues in the cultural committee: No matter how urgent the appeals for aid were, they were in favor of leaving a cash reserve for emergencies.

In the light of the misery which I had observed and of the constant financial danger threatening religious institutions from Romania through Lithuania, I would always urge that we send whatever monies we had to stop the gap, and to rely for emergencies on the help of G-d and the generosity of our American brethren.

At one meeting, I must have become more eloquent than usual and my colleagues agreed with my passionate plea to send whatever we had left, in answer to a desperate request from the heads of the Yeshivos. That happened on a Monday.

On Tuesday morning, I received a cable from the Chofetz Chaim asking for 25 hundred dollars for a “new, elegant” mikveh to be built in Vilna. Owing to my “victory,” we had no money left in our treasury.

I conveyed my embarrassment to several of my friends in the Center and was able to get $1,750 from three of them. As, on Thursday, I entered the meeting at the Joint, I said to my colleagues: “Hatati, Aviti, pashati — It’s all my fault and sin, I do not know what to do. I have most of the money but I need $750 more.” I was deeply moved when Alex Kahn responded: “Would you accept $500 from our funds for the mikveh? I should consider it a privilege to contribute.”

To me it was an indication of the high level of American Jewry that the desire to help our brethren bridged over the chasm of theological differences.

Rabbi Jung cherished his relationship with the Chofetz Chaim and would often study his sefer on shemiras halashon with his congregants. He loved to recount his memories of the 1923 Knessiah Gedolah when the Chofetz Chaim looked him square in the eyes and said to him that he (Rabbi Jung) was going to bring Yiddishkeit to America, that he was going to save American Jewry from assimilation and disappearance. With a twinkle in his eye, Rabbi Jung would then tell his congregants, “I will cherish the memory of our meeting as long as I live: his eyes, his face, the words he spoke, never vanish from one’s happy soul.”

When Rabbi Jung could not extract funds from the Joint for the building of Yeshivas Kol Torah in Yerushalayim, he turned to longtime Jewish Center President Max Stern, who seized the opportunity to dedicate the yeshivah’s Bayit Vegan campus, which is currently enshrined with his name.

This Is My Rabbi

In a 1984 interview with Professor Monty Noam Penkower, Rabbi Jung was not ashamed to proudly refer to himself as someone who spent the previous 60 years as a schnorrer. However, he did so much “schnorring” for so many different causes, that even his most prolific benefactors often got confused amid the barrage of appeals that came their way.

Author Herman Wouk was a longtime congregant and close admirer of Rabbi Jung, whose persistent efforts led to Wouk’s return to Orthodoxy as a member of the US Navy during World War II. Wouk was a willing partner to Rabbi Jung in his many holy causes. Torah Umesorah, Chinuch Atzmai, Mesivta Tiferes Yerushalayim, and the Mir Yeshivah were all beneficiaries of his largess. Wouk took a personal liking to the Bais Yaakov movement and donated generously for several decades. A 1963 letter from Wouk that I came across in Rabbi Jung’s extensive files, well illustrates a confusing situation:

Dear Rabbi Jung:

I am writing to you for clarification of the scope of the BETH JACOB WORLD ORGANIZATION. Your signature appeared on a general letter of appeal dated the eve of Rosh Hashanah. Of course, I wish to contribute.

My puzzlement lies in the large number of organizations with the name, BETH JACOB, all of them apparently directed to the education of girls, which have addressed me for funds this year. I would like to know, if I can, to what extent these institutions are interrelated or overlapping; or if they are wholly independent of each other. I need this information in order to make an appropriate allocation of funds.

Here is a list of the “Beth Jacob” organizations that appealed to me this year, commencing with the one for which you wrote the letter.

The letter goes on to list nearly a dozen different Bais Yaakov schools and entities across the world, all of which Rabbi Jung was intimately involved with and raised funds for.

When Wouk’s bestseller This Is My G-d was released to critical acclaim in 1959, Dr. Joseph Kaminetsky wrote a very positive review in a Torah Umesorah publication. When someone complained to the organization’s Rabbinical Administration about it, gedolei Yisrael were fast to come to his defense. Dr. Joe described the brouhaha:

Reb Yaakov Kaminetsky, sage and peacemaker that he was, tried to quiet his esteemed colleague: “What’s the gevald?” he asked. “You’re taking a particular passage out of context. Why G-d forbid, were you to take a passage of the Chofetz Chaim out of context, you might have doubts about him too!”

These sweet, gentle words only further infuriated my beloved critic. (Really, he and I were great friends most of the time.) It was then that Reb Moshe stepped in. He knew Herman Wouk well. His son-in-law, Rabbi Moshe Tendler, had been Wouk’s adviser on religious matters for the book. When my critic actually stood up to his full height and further excoriated Wouk and his work, Reb Moshe, who was short of stature, stood up also, looked right into the man’s eyes, and cried: “I want you to know that Herman Wouk (whom he knew intimately) is as frum as you — or frummer!” That ended the argument.

Rabbi Jung was an honored guest at the 1947 dedication of the Dushinsky Yeshiva in Yerushalayim. (L-R) Rav Yosef Tzvi Dushinsky, Dov Berish Weidenfeld (Tchebiner Rav), Rabbi Leo Jung (speaking) Rav Avraham Yochanan Blumenthal, Rav Pinchas Epstein, Rav Lipa Mayer-Teitelbaum (Sassov-Sejhmilay Rebbe), Rav Eliezer Yehuda Finkel (Mir Rosh Yeshivah)

The Right Man for the Job

Legendary Torah Umesorah leader Dr. Joseph Kaminetsky (known fondly as Dr. Joe) was one of Rabbi Jung’s prized students in the early 1930s at yeshivah, and served as Rabbi Jung’s assistant rabbi and a teacher (and later the principal) at the Jewish Center Talmud Torah from 1934–1946. When Dr. Joe answered the call of Rav Shraga Feivel Mendlowitz to lead Torah Umesorah, Rabbi Jung joined him as a “partner” in the project. Donor rolls from early TU appeals are filled with Jewish Center balabatim. Rabbi Jung served on the organization’s rabbinical advisory board alongside venerable Torah Leaders like Rav Aahron Kotler and Rav Reuven Grozovsky.

Soon after he was hired by Rabbi Jung, Dr. Joe began to pursue the vacant rabbinic position at Baltimore’s Shearith Israel Glen Avenue Shul. He was impressed by the fact that the shul only accepted shomer Shabbos members and figured that this would be an excellent launching spot for his rabbinic career. Dr. Jung agreed and offered a ringing endorsement of the young rabbi.

Soon afterward, Rabbi Jung traveled to Switzerland where he annually summered. It was there that he met a young Rabbi Shimon Schwab who asked his help in obtaining a rabbinical position in America, where he hoped to find safety with his family. Rav Schwab’s son, Rabbi Moshe Schwab, related that Rabbi Jung told his father that he had recently read his book Heimkehr ins Judentum (which was published a year prior) and that based on the views expressed in this book, there would be only one suitable rabbinical position for him in America, that of Shearith Israel in Baltimore, where a position happened to be vacant since the passing of Rabbi Dr. Schepsel Schaffer, who died in 1933.

Dr. Joe related what happened later that summer. “Rabbi Jung called me into his office, and he took out a book in German written by a Rabbi Shimon Schwab and calmly told me that the congregation was bringing this man from Germany to assume the position. Somewhat nettled at the idea that the congregation had chosen their spiritual leader sight unseen, without the least personal introduction, I told Rabbi Jung that if that’s the way a rabbi was chosen, I’d better stick with education.”

At the time, Dr. Joe relates, he had no idea that Rabbi Jung, in his mercy and wisdom, was using his personal leverage to rescue Rabbi Schwab and his family from the Nazis and had the intuition to understand that Rabbi Schwab would be a great asset to the community, even with his rudimentary English. Dr. Joe writes, “It turned out, of course, that Rabbi Schwab became one of the foremost spiritual leaders of American Jewry!”

Patron of the Yeshivos

Rabbi Aaron Rakeffet relates the incident that occurred when Rav Elchonon Wasserman was a guest of Rabbi Jung at the Jewish Center while on a fundraising visit from Europe. Rav Elchonon disagreed with the Jewish Center’s gentile-operated “Shabbos elevator,” and according to some sources, refused to daven there. That did not stop Rabbi Jung for pleading for funds for him at the shul or at the JDC, from whom he obtained additional funds for the Baranovich Yeshivah.

Rabbi Jung also had a unique relationship with the roshei yeshivah of Telz and took a liking to their unique style of education. When the Nazis rose to power in the early 1930’s, German Jewish students — who were no longer permitted to study in universities — flocked to Eastern European yeshivos like Telz, Mir, and Kaminetz. Rabbi Jung saw this as an opportunity to draw more funding from the Joint, which had set aside monies for refugee German students, so he devised a program whereas the Joint allocated handsome monthly disbursements to yeshivos for these talmidim. These funds came in addition to the usual stipends from the Joint and helped the yeshivos subsist through difficult times.

When the Telzer roshei yeshivah arrived in America, Rabbi Jung hosted a fundraising dinner for their new yeshivah in Cleveland, and was the guest of honor and speaker at several other Telz benefits through the 1940s and ’50s.

Perhaps no yeshivah benefited more from Rabbi Jung than the Mir. Dating back to the mid-1920s, he shared a close bond with Rav Avraham Kalmanowitz, Rav Leizer Yudel Finkel, and later his son and successor Rav Beinush. It was the JDC which funded the lion’s share of the costs to transport the Mir Yeshivah to Japan and provided it with a regular stipend, beyond what other refugees received, to cover the costs of kosher food during its time in Japan and Shanghai. When disputes occurred between the Vaad Hatzalah and the Joint, it was Rabbi Jung who worked with Rav Eliezer Silver to try and smooth out the issues.

When Rav Leizer Yudel came to America in 1948 to raise funds to rebuild the Mir Yeshiva in Yerushalayim, Rabbi Jung helped him obtain a large gift from his congregant Samuel Kaufman and his son Benjamin to build the majestic Kaufman Family Building that stands on Rechov Bais Yisrael today. Funds also came from the Kaufman family to help build the Mirrer Yeshiva in Brooklyn.

Beginning with his 1935 trip to America on behalf of Kletzk, Rav Aharon Kotler developed a kinship with Rabbi Jung that lasted for more than a quarter of a century. Minutes from a JDC board meeting in early 1942 show that a rare guest was invited to attend and make a presentation to the group on the state of the refugee yeshivos. It was none other than Rav Aharon, whom Rabbi Jung insisted on hosting to impress upon the mainly secular group the importance of the cause. When Rabbi Jung faced difficult questions as a member of the Jewish Welfare Board Chaplaincy Commission, he discussed them wtih Rav Aharon.

Rabbi Jung became Rav Aharon’s partner in many vital causes, including Torah Umesorah, Chinuch Atzmai, and the Chofetz Chaim Yeshiva on the Upper West Side, where Rav Aharon first resided upon his arrival in America. Rabbi Jung also helped Beth Medrash Govoha in its early days via Samuel Kaufman and other Jewish Center members.

Eulogy for a Mobster

From its inception, one of the leading members of the Jewish Center was Abraham E. Rothstein, a charitable, wise and learned man who was known across New York as “Abe the Just.” He earned the nickname following his public refusal to declare bankruptcy after his cotton goods business went under because of World War I.

Rothstein served as the treasurer of the Jewish Center Torah Society, which assisted a great many yeshivos and needy rabbis, and later served as a nationally renowned mediator, helping to resolve labor disputes and other difficult scenarios.

But as pious as Abe Rothstein may have been, his son Arnold did not follow in his path. He fell in with the wrong crowd and quickly got involved in bootlegging, gambling, and racketeering. By the time he was in his twenties, Arnold Rothstein had a reputation as a mobster. When he married out of the faith, his father allegedly sat shivah and cut off his relationship with his now-infamous son.

Rothstein was perhaps most infamously known as the man suspected by many of engineering the Chicago “Black Sox” baseball scandal, when players threw the 1919 World Series after allegedly receiving cash payments from Rothstein’s agents, who placed a large bet on the opposing team. Even with the public eye fixed upon him, he continued his unsavory actions. With the advent of Prohibition in 1920, he saw the economic opportunities bootlegging offered and he essentially became the architect of modern organized crime.

On November 4, 1928, he was gunned down at the Park Central Hotel in Manhattan. A day later he died. When Abe Rothstein asked Rabbi Jung if he would officiate at the funeral, there was no question as to whether he would comply.

Nearly 30 years later, Rabbi Jung received a letter asking him about the episode, allowing us a window into his thinking:

Dear Rabbi Jung:

At a recent meeting of a group of young rabbis in town, the question of practical rabbinics was discussed. It was pointed out that many years ago you were called upon to officiate at the funeral of the late Arnold Rothstein. The question posed was: Is it true that you officiated and, second, should one in the rabbinate hesitate to officiate at the funeral of a man whose reputation during life was not too enviable?

I would appreciate your thinking in this matter.

Sincerely yours,

Rabbi William Novick

Rabbi Jung was quick to respond, penning this letter back:

Dear Rabbi Novick:

Mr. Arnold Rothstein’s father was one of the noblest men in New York Jewry. When his son was murdered his request for officiating at the funeral could not be denied. I spoke very briefly about the father’s great achievement and about his abysmal pain; about G-d being the only one who can judge adequately, especially a dead man, and I ended with the prayer for his parents’ health and strength to bear their grave burdens.

All these details are quoted to indicate that one cannot offer a general counsel: Each case must be judged by its own context.

Hoping these notes will help you and with every kind wish, believe me to remain,

Sincerely yours,

Rabbi Leo Jung

Give with Dignity

When Rabbi Jung first started at the Jewish Center, he was faced with an issue. His appreciation and respect toward Torah scholars were such that he would not turn down any rabbi who approached him for help. He just simply could not say no. To fund this growing endeavor, Rabbi Jung founded the Rabbanim Aid Society, for which he raised funds from wealthy congregants and friends.

The distribution of the funds by Rabbi and Mrs. Jung was far from a passive endeavor. In addition to those who approached him, Rabbi Jung sought out needy rabbanim and sent them funds regularly, often secretly or by way of an intermediary. Manhattan Rabbis Zev Tzvi Vorhand and Shmuel Orenstein were two of those who often assisted Rabbi Jung.

Dr. Joseph Kaminetsky recalled how Mrs. Jung often involved herself in these cases intimately. When his mother asked him to obtain some assistance for a local Brownsville rabbi, Mrs. Jung came to the rabbi’s home, helped fix up the decrepit apartment, and even arranged for the aging rabbi to get a badly needed new set of teeth.

One rabbi who was embarrassed to receive charity funds insisted on meeting Rabbi Jung at a neutral location to receive his check. Rabbi Jung respected his wishes and regularly traveled to their clandestine meeting spot, rain or shine. Mrs. Jung related, “I was afraid to buy him a new coat because he would give it away.”

Amazingly, in reading Rabbi Jung’s memoirs, he bypasses much mention of the hundreds of poor rabbanim he assisted and instead utilizes its pages to share lessons he learned as a result of being involved in the administration of charity. I found two of Rabbi Jung’s stories particularly inspiring:

A few years ago, a wealthy friend brought me a precious fur-lined coat, suggesting that I bestow it upon one of the poor rabbis in our Society. That coat, both warm and beautiful, had been worn by her late father for less than six weeks; it looked perfectly new.

Gratefully I began to search for the scholar whom the size would fit. When I discovered one, I invited him to my study for a learned conversation at the end of which, diffidently, but cheerfully, I told him I had received this gift which was too small for myself, that I greatly appreciated its beauty, and I would be much obliged if he would be good enough to accept it. It would protect his health during the cruel winter.

His face was a study. Appreciation and pain struggled for mastery. Finally, he said very gently: “I’m very grateful for the monthly check your Society favors me with. You can’t appreciate what it means not only in terms of economy but of the manifestation of genuine friendship. But forgive me, I cannot possibly wear another man’s coat.” I put my arm affectionately around his frail body and begged for his pardon.

Something of the same nature but less dramatic happened in 1969. Before Succos I receive a few etrogim every year from Israel which I am lucky enough to be able to distribute among non-opulent colleagues. Having received a large number this year, I called up a very poor Brooklyn scholar and asked him whether I could send it to him. His answer was: “Please don’t misunderstand me. I appreciate your thoughtfulness but one of the privileges I cannot give up is choosing my own etrog.” I’m grateful for the lesson.

Holocaust Rescue

Perhaps most noteworthy among Rabbi Jung’s achievements was his Holocaust era rescue work, which was nothing short of breathtaking. His regular summer trips to Europe gave him a close vantage point of the impending doom.

Rabbi Jung was always dubious of the promises made by various governments to provide shelter to the Jews. He recalled meeting Winston Churchill along with Dr. Yitzchok Breuer in London in 1919, to plead for help for the Jews of then British Palestine. Churchill told them, “Of course we shall try to cajole the Jewish position of importance, provided it doesn’t interfere with the lifeline of the Empire.” Whenever he recounted that meeting, Rabbi Jung would conclude with the following allegory: “You know what an infamous British general said when someone said, ‘Why don’t you save the Jews?’ He said, ‘What shall I do with a million Jews?’”

His biographer Dr. Marc Lee Raphael recorded Rabbi Jung’s heroic work during the dark years of the Holocaust. “He appealed from the pulpit, he wrote letters, and made house calls to convince congregants to guarantee room and board as well as temporary living expenses pending employment, for a refugee. He personally collected more than 1,200 affidavits that led to the rescue of over 9,000 Jews, a number that is surely the largest among individual Jews.” (It’s also perhaps larger than many of the rescue organizations that had greater access to important resources and funds.)

As busy as Rabbi Jung was, he also made time to help teach the young leaders of Zeirei Agudath Israel, Mike Tress and Rav Gedalia Schorr, the process of obtaining visas and affidavits. Rabbi Jung also provided the funding to pay for the Williamsburg headquarters of the Zeirei at 157 Rodney Street.

Austrian Agudah leader and activist Julius Steinfeld was saved as a result of a persistent campaign by the Agudah Youth and Rabbi Jung. Upon his arrival in New York, he would spend entire days and nights working with Rabbi Jung on rescue cases.

Rav Hutner’s Hand

After surviving the horrors of the Holocaust, 22-year-old Rabbi Shlomo Carlebach, son of the aforementioned Rav Yosef Tzvi Hy”d, arrived in New York in June 1947. His cousin, Rav Simcha Zissel Levovitz, brought him to Rav Yitzchok Hutner, hoping he would give a chance to the young man who had not studied Gemara in more than six years. Rav Hutner paired him as a chavrusa with a fellow Yekkeh, Yosef Loebenstein, to help him make up for lost time and propel him ahead in his learning. By the end of the summer, he was sufficiently proficient to join Rav Hirsch Levenberg’s shiur (first year beis medrash). The bochurim looked askance at this strange young man six years older than them, but eventually they became his closest friends.

At the end of the summer, he went to the offices of the JDC, which was financially responsible for war survivors. The case worker he was assigned to asked him what his plans were for a career.

He answered, “My goal is to study for the rabbinate and follow in the footsteps of my late father and grandfather, who were lifelong rabbanim.”

The case worker answered: “Here in America we have no need for tzitzis-shpinners, we only help people who will roll up their sleeves and work! The Joint will not be helping you. Goodbye.”

He was penniless and had no source of support. He told Rav Hutner how the interview had ended.

Rav Hutner said, “There is a rav in Manhattan who certainly knew your father and probably even studied at the Berlin Rabbiner Seminar, Rav Eliyahu Jung. He is a member of the board of the Joint Distribution Committee. Phone him and tell him who you are, and your whole story and your experience with the Joint.”

He called Rabbi Jung and introduced himself. Rabbi Jung said, “I am amazed to hear of your survival and your plans, it is an honor to do anything for a son of the Hamburger Rav.”

On Erev Yom Kippur a telegram came to the yeshivah addressed to him: “Rabbi Leo Jung wishes you a good year and you have an appointment at the Joint the morning after Yom Kippur.”

This time it was a very different experience. The secretaries welcomed him like a VIP and ushered him into a senior management office. Here they told him, “The Joint is happy to sponsor your rabbinical studies. You will receive a monthly stipend as long as you continue your rabbinical courses.”

The stipend enabled him to learn without needing to ask anyone for favors and continued for ten years. One of the great teachers of Torah of the past half-century and the author of the classic Maskil L’Shlomo is just one more person eternally grateful to Rabbi Leo Jung.

Rav Eliezer Silver visits Rav Michoel Ber Weissmandl and the Nitra Yeshiva (1903-1957)

A Home for Nitra

One of Rabbi Jung’s immediate postwar projects was the assistance he provided for Rav Michoel Ber Weissmandl to reestablish himself and his unique vision of a Torah agricultural institution in the United States. That relationship began in 1946, when Rabbi Jung received word that a contingent of Hungarian yeshivah student Holocaust survivors had entry visas to the United States and required financial assistance for ship fare, which was extremely costly. He secured funding from the Joint and went to greet the group and its leader, Rav Michoel Ber Weissmandl. Rav Weissmandl was a great Torah scholar in civilian life, and a legendary rescue activist during the Holocaust.

Rav Weissmandl greeted Rabbi Jung. “I won’t thank the Joint or yourself. It is impossible to express what I and my group feel, but I should like you to know that in bringing over the remnants of our yeshivah, I do not want them to live on charity. My plan is to combine learning with agriculture. I want our students to study G-d’s law and to earn their living by the sweat of their brow.”

Rabbi Jung arranged for Rav Michoel Ber to set up a yeshivah and settlement on a property in New Jersey. The attempt failed, however, and Rabbi Jung once again came to the rescue of the Nitra Yeshivah of Rav Weissmandl. Rabbi Jung recalled:

“One day he came with a glowing face to tell me that a beautiful estate in Mount Kisco was for sale. It had enough acreage, buildings, and other facilities for a yeshivah farm settlement. He had meantime collected a group of friends who were willing to help him.

This million-dollar estate, he told me, was available for three hundred thousand dollars. I asked him how much money he had in the bank and he answered truthfully: ‘about one hundred and fifty dollars.’ Sadly, I asked him to forget about this hope.

It was a time when the government had begun to tax landed estates heavily, and within four weeks Rabbi Weissmandl came back to inform me that that estate was now available for one hundred thousand dollars and that he actually had fifteen thousand dollars in the bank, collected from friends more enthusiastic than endowed with worldly goods. He needed “only” another eighty-five thousand dollars and he looked for me as ‘his first and best friend in America,’ somehow or other to produce it.

As he talked to me, I suddenly remembered an encounter some years ago with the philanthropic tycoon, Mr. Israel Rogosin of blessed memory.… Within two weeks Mr. Rogosin gave Rabbi Weissmandl a mortgage, without interest, of eighty-five thousand dollars. Within six months he tore it up. It became a most precious gift.”

The saga wasn’t over. The residents of Mt. Kisco — primarily assimilated Jews — protested when the yeshivah moved in. To their narrow minds, the bearded scholars with their outlandish dress and manner spelled definite danger to the Jewish inhabitants of that exclusive neighborhood.

Rabbi Jung recruited aid from local non-Jews, who were ironically more sympathetic to the plight of these hapless Holocaust survivors’ attempts at rebuilding their religious life in an agricultural framework. In addition, Rabbi Jung found unaffiliated local Jews, though distant from Jewish tradition, still galvanized to support the Mt. Kisco yeshivah and stave off the protests.

Presenting President Harry Truman with the first English translation of his close friend Rav Menachem Kasher’s Torah Shelemah in the Oval Office

Because He Cared

Upon Rabbi Jung’s 70th birthday in 1962, a tribute sefer unlike any other was published in his honor. The unique Sefer Hayovel was filled with essays from Torah leaders including Rav Shlomo Zalman Auerbach, Rav Yosef Eliyahu Henkin, Rav Zalman Sorotzkin, Rav Yechiel Yaakov Weinberg, Rav Reuven Katz, Rav Yechiel Mordechai Gordon, Rav Mordechai Gifter, Rav Isser Yehuda Unterman, Rav Shmuel Ehrenfeld (The Mattesdorfer Rav), and Rav Yochanan Sofer (The Erlau Rebbe) to name just a few. Their stature is a true testament to the esteem garnered by this giant among men.

Rabbi Amos Bunim recalled the hesped that Rav Aharon delivered at the funeral of Rabbi Jung’s congregant, the great Torah supporter Samuel Kaufman, on Chanukah of 1960 at the Jewish Center: