Luck of the Draw

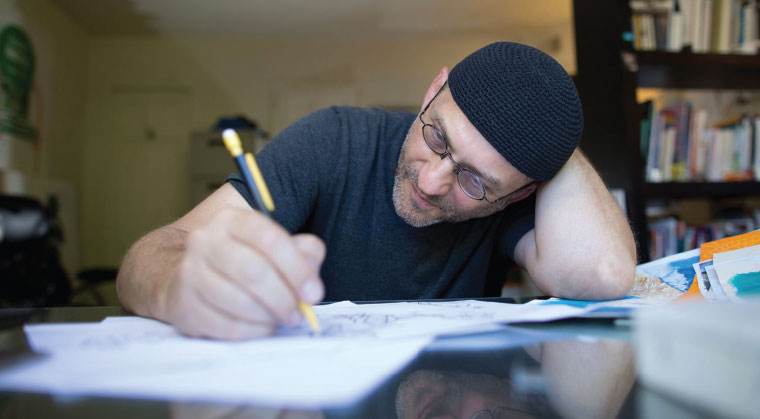

STORYTELLER “As artists we should be able to tell our stories just as they are without crafting every book into an educational message that hits the reader over the head” says Lumer

"E dgy” isn’t usually a word that’s used to describe illustrations for frum children’s books but French-born Los Angeles artist Marc Lumer isn’t your typical frum illustrator. One of the first things a person sees when walking into Marc Lumer’s art studio on the second floor of his home is a large bright-yellow Pop Art–style painting of a fire hydrant with Hebrew letters gracefully escaping from underneath.

Torah is water Lumer explains adding “So what better metaphor should represent how it flows in all things than a fire hydrant?”

What indeed? And just as this is not the usual traditional painting that your elter zeide would have hung on his living room wall neither are the nine children’s books and one graphic novel that Lumer illustrated and cowrote.

“I feel like I’m on a mission to put Jewish children’s books out there that are more about imagination emotions and a sense of destiny” says Lumer who has two new children’s books scheduled for publication this fall. Babel is a humorous and innovative retelling of the story of the Tower of Babel episode (Apples and Honey Press) while My Little Prayer and Story Book from the Western Wall (Western Wall Heritage Foundation) recounts the history of the Kosel Hamaaravi from the perspective of one of the stones.

“So often Jewish children’s books focus on ‘teaching a lesson’ or ‘making a point.’ But simply telling stories about our lives as frum Jews in imaginative creative ways should be enough of a plot to make a great book. I just want to tell stories about things that happen in families like mine.”

Telling Our Stories

In addition to the many colorful paintings on the walls of Lumer’s studio are a collection of toys for Benny his eight-year-old son. Benny isn’t just a companion in his studio but also an inspiration. For instance Benny’s Mitzvah Notes (Hachai Publishing) is about a little boy whose mother writes him a mitzvah note while his father adds a little drawing every day. Lumer conceived the idea for Benny’s Mitzvah Notes after his son’s nursery school morah made a book of her students’ many mitzvah notes at the end of the school year. When Benny brought his book home Lumer felt the book resembled the comic books he grew up with in Europe where he spent much of his childhood. He decided to write about a father’s love for his son that went along with the drawings.

“Loving my son isn’t necessarily about things like taking him to baseball games” Lumer says. “Part of me loving my son as a Jew is expressed in making a drawing on his mitzvah note every morning.

“I love the idea of telling stories where our values come through as part of the story” he says. “Life is a journey and it’s full of good things and bad things. You meet people they affect you and things happen to everyone that aren’t fair or expected. As artists we should be able to tell our stories just as they are without crafting every book into an educational message that hits the reader over the head.”

Boot Camp with Disney

Lumer was born in La Tronche a small town in southeastern France. When he was six months old Lumer’s family moved to Seattle where both his parents taught mathematics at the University of Washington. After several years the family returned to France where his parents were instructors at École Normale Supérieure in Paris. Later when his father received an invitation to teach at the Université de Mons they moved to Belgium.

According to Lumer he’s been drawing and sketching as far back as he can remember. A fan of the popular European comic book The Adventures of Tintin which is about a cute blond boy and his dog Lumer used his creativity to remake Tintin into a hero he liked better: a boy who was bald and had a patch on his eye.

“I think I already had a quirky sense of humor and I thought Tintin was too squeaky clean” Lumer says with a smile. “I thought you could be funny-looking and still be a hero and have adventures.”

Those early sketches prepared Lumer for some of his first jobs after he studied art at La Cambre one of Belgium’s leading schools of art and design. He began publishing comic strips for Tintin and Spirou another popular youth magazine in Europe while working as a freelance illustrator for a variety of European advertising agencies magazines and publishing companies. He also worked as an art director for Tintin’s apparel line.

In 1994 Lumer moved to Los Angeles where he freelanced at Disney and worked at Warner Brothers. In 1996 he joined the creative team at DreamWorks which was then a new animation film studio created by Steven Spielberg Jeffrey Katzenberg and David Geffen. One of the projects he worked on was the animated feature film The Prince of Egypt.

“I saw how they made a $100 million movie out of the story of Moshe” Lumer recalls. “People in my community didn’t like everything in that movie but I loved the idea of creating kosher entertainment for children. I love to find Jewish stories that have wider appeal.”

He also loved the opportunities he was receiving to hone his craft. “Working in the Hollywood studios made me a much stronger artist than I was when I came in. It was like going to boot camp in the sense that I improved many aspects of my craft that were weak. But at a certain point I wanted to do my own work and not just other people’s cartoons.”

A Jewish Home of His Own

While Lumer was considering where he wanted to go with his career, he moved to the Jewish neighborhood of Fairfax/La Brea, one of L.A.’s oldest frum neighborhoods. His initial reason for moving was to shorten his commute to work, but he soon became friendly with his frum landlord.

“My landlord, Isaac Fuchs, became a good friend,” Lumer remembers. “We had a lot in common, because his family, like my father, also came from Germany.”

Lumer also was struck by the beauty of a frum family. “I had never wanted children before,” Lumer says. “I didn’t really like children. I found them really annoying. I was one of those people who would move seats if small children sat next to me on airplanes.

“However, I started to get to know the Fuchs and their four teenage children, and I saw this beautiful, amazing family. I was really struck by how smart the kids were and how much of a moral compass they clearly had. I knew this was the lifestyle I wanted for myself.”

Lumer was in fact so struck by his friend Fuchs, whom he calls “a hidden tzaddik,” that he used him as a model for the cover of his children’s book When Miracles Happened: Wondrous Stories of Tzaddikim (Targum Press).

Other people in the community started to invite Lumer for Shabbos meals and to learn with them. He started attending Congregation Tifereth Zvi, one of L.A.’s oldest shuls. “Teshuvah was something I think I always had in me,” Lumer says. “Little by little, I felt a shift inside of me.”

In fact, Lumer was learning so much Torah that, for the first time in his life, he had to stop drawing for a while. “When I do something, I do it 100 percent. I just couldn’t draw and learn Torah so intensely at the same time. Learning Torah was taking all of my mental energy.”

If he wanted to be a Torah-observant Jew, Lumer knew he needed to make some changes in his life. He quit his Hollywood job and broke with his non-Jewish friends. Two years later he married Miriam, who was born in Montreal and had two children, an 11-year-old boy and a 12-year-old girl, from a previous marriage. Three years after that, Lumer and Miriam had Benny.

“A Jewish home was what had inspired me to do teshuvah, and I saw that the woman is really the person who creates the Jewish atmosphere in the home,” Lumer says. “I really have my wife to thank for giving me such a beautiful Yiddishe environment. Miriam gave me what I never had, a Jewish home, and that is what is most important to me.”

Chabad Calling

After leaving the world of Hollywood animation studios and trying to launch his own publishing company, Lumer found work as an art director at an advertising agency in his Jewish neighborhood, where the lighter work schedule and demands allowed Lumer to slip out of his office at lunch and attend shiurim at a nearby kollel on La Brea Blvd.

But when many of his colleagues became unhappy because of the restrictions on Lumer’s time due to his religious observance, he branched out on his own to create Marc Lumer Design.

“At advertising and graphic design agencies, people regularly work nights and weekends, so I got a lot of resentment from a lot of other designers,” Lumer explains. “I realized that I can’t be frum and work for anyone else.”

Confident of his considerable talents, Lumer thought starting his own firm was going to be easy and that he would find clients immediately. Then reality hit.

“At first, I had no clients,” Lumer admits. But soon he began to see what he describes as “miracles.” Perhaps as a middah k’neged middah for Lumer’s decision to work only during kosher times, his new company’s first job was for a kosher restaurant.

Aharon Klein, the owner of the popular Fish Grill in Los Angeles, happened to be one of Lumer’s Shabbos hosts. Klein asked Lumer to redesign an additional location of the restaurant on Wilshire Boulevard, (now closed). For the Fish Grill, which has three other locations in Los Angeles and Malibu, Lumer created a new logo, an interior design, and a wall-sized artistic mural to catch customers’ eyes.

One day, one of the heads of Chabad of California, Rabbi Chaim N. Cunin, walked into the renovated restaurant to eat dinner. Rabbi Cunin was so struck by Lumer’s artwork that he asked for the name of the painter. Lumer “happened” to be there and Rabbi Cunin introduced himself. He told Lumer that he was looking for an artist to rebrand Chabad of California. The job included graphic design work and rebranding for the Chabad Telethon and their magazines Farbrengen and Jewish Impact.

In 2007, Lumer created a twist on the standard, large Chabad menorah by designing an eye-catching, clear Plexiglas one for the 17th Annual Capitol Menorah Lighting Ceremony at California’s capitol in Sacramento. Lumer also designed an 18-inch glass replica of the menorah for Chabad of California director Rabbi Shlomo Cunin to present to then-governor Arnold Schwarzenegger, as a token of appreciation for his participation in the menorah lighting. But of all the projects that resulted from the artist’s association with Rabbi Cunin, the one that makes Lumer most proud is the cover design and 200 illustrations he did for the Kehot Chumash.

“Although my artistic style is usually on the edgy, creative side, I really took a lot of enjoyment from just purely and accurately servicing the content of the Chumash,” Lumer says. “I loved showing those parts of the text that are hard to visualize, such as the way the table in the Mishkan looked and how the spoons were tucked into the table, between the two rows of show bread.”

That’s Not All, Folks

Among the many projects in the mix right now for Lumer are an illustrated book about the life of Rashi, a children’s book called The Adventures of a Golem in New York, and the art direction of a new children’s book of gorgeous paper cuts about the Creation of the world and illustrated by Los Angeles–born artist Dena Ackerman, who now lives in Ramat Beit Shemesh.

The idea for Babel came to Lumer while flying home from his mother’s levayah in 2009. He says he wanted to create a children’s book about the story that was fun, cartoony, and creative — while being true to Torah.

“I put tower hats on the people, who were singing a tower song and eating a tower cake, because we wanted to create a fun and quirky way to illustrate that concept — one that kids could relate to. So, my cowriters Chaim Burston, Dov Naiditch, and I took the idea and tried to express it in a way that is similar to what happens today when there is a craze for something that is not appropriate, and every aspect of it is merchandised like there’s no tomorrow.”

Before Lumer returns to his drawing board, literally, he shares one last thought. “I love to tell stories that are true to Torah. I’m just trying to tell stories that are a little more entertaining. A Jewish book will spark a kid’s interest if it has exciting images and real stories that speak to his or her soul.”

The Art of Work:

“Working as an artist can be a great profession for frum people,” says Marc Lumer. “You can work out of your home and make your own hours, which allows parents to be home with their children and have no conflicts with chagim and Shabbos.”

However, when asked to advise young people who may want to pursue careers in the visual arts, Lumer likened his attitude to a rabbi who is approached by a potential convert to Judaism.

“A rabbi rejects geirim twice before they are taken seriously. I would use the same kind of cautious attitude toward religious people who want to use their artistic talents to support their families.”

One reason why Lumer is somewhat hesitant to encourage aspiring artists is that jobs can be unpredictable. And once you land the job, there’s an expectation that you’ll work as many hours as it takes to get the job done on time — even if that means working late nights and weekends.

Lumer also emphasizes that creative people have to be honest with themselves about how much art they want to and are able to create. Working artists, he says, are not people who occasionally “get inspired.”

“A working artist is someone who wakes up every morning with a burning desire to create something,” Lumer points out. “Even if you aren’t bringing in money with your art, an artist is someone who wants and needs to draw, paint, and/or write every day. People without that drive will not survive in the competitive environment of the art world.”

For those who still aren’t deterred, Lumer offers several pieces of advice:

“First, the support of parents can be helpful. Parents can provide art lessons, guidance, and trustworthy mentors. Second, people who want to work in the arts should experience firsthand the life of a working artist. Artist internships are great opportunities for apprentices to create professional-looking portfolios and get feedback on their work. Working artists can help less experienced artists to fine tune their skills.”

Lumer speaks from experience because he interned with people working in animation when he was a teen. It’s also important to get some professional training at an art school, and he comments there are a few that provide an acceptable environment, such as Touro College in Manhattan and Brooklyn, and Onan, the Charedi Extension of the Bezalel Academy of Arts and Design in Jerusalem. “Artistic training is important,” Lumer says, “but our way of life is so much more important.”

Although working as a frum professional artist isn’t easy, some people do succeed, Lumer says, pointing to a handful of illustrators, fine artists, story board artists, cartoonists, and producers who are able to support themselves with their art.

“People with talent, focus, and determination will pursue their artistic dreams no matter what. When people’s work is their passion, they will work twice as hard, and that is the way to succeed.”

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 632)

Oops! We could not locate your form.