Lower California Is Not for Sale!

| April 9, 2024Each plan offered a glimmer of hope against the backdrop of closed doors and limited options for Jewish emigrants facing imminent peril

Title: Lower California Is Not for Sale!

Location: Baja California, Mexico

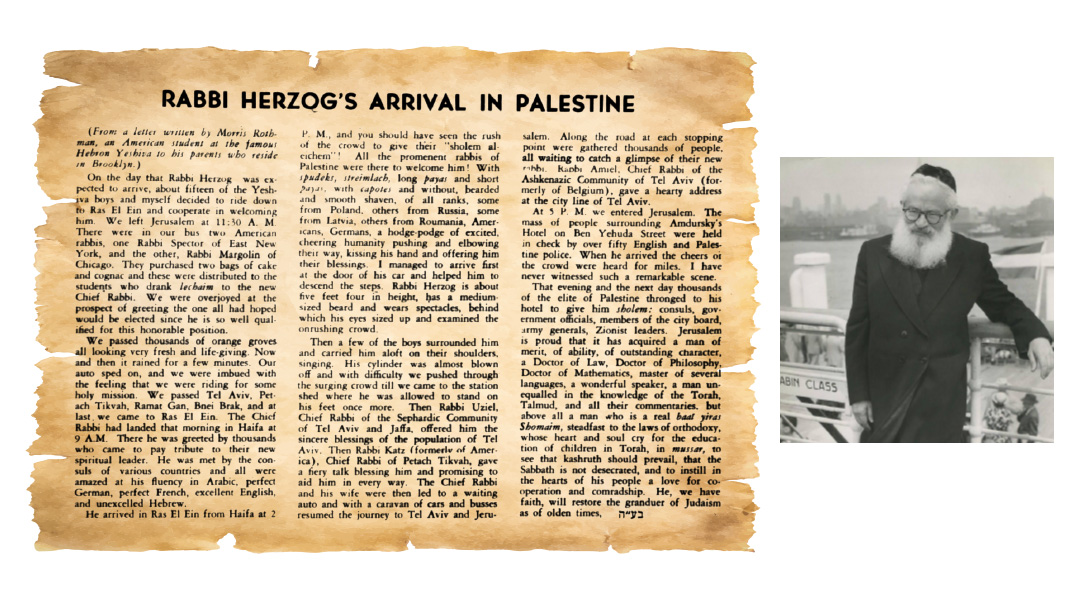

Document: The Jewish Forum

Time: February 1938

Jewish conditions today are desperate. A way must be found out of the impasse.

That madhouse called Europe, lately encouraged in its madness by the vacillating policy of England and France, is no safe place for the Jew. For Jews first to escape from Germany to Austria, from Austria to Czechoslovakia and Hungary, and from these countries into G-d knows what other trap, will merely aggravate the condition.

It is time that Jews be permitted to direct their destiny by constructive work and live as human beings, without being hounded, in at least one spot in the world, where they might give expression to their idealism — the idealism of the Prophets and Sages of Israel, the idealism that has given birth to an era called the age of civilization. In return for the blessings the Jew has conferred on mankind, the world owes him the privilege of breathing G-d’s air unmolested. Why continue to keep him as a scapegoat?

Demonstrations and protests seem to have exhausted their effectiveness. The conscience of the world appears to be dormant. The ancient home of the Jew would have been the solution if the Mandatory Power had kept its promise. Treaties no longer seem to be sacred. While the Jew will never forsake his spiritual attachment to the Land of Israel, and while his zeal for the Holy Land and his undying courage will continue to impel him to every sacrifice in support of the heroes who are building the Jewish Homeland, his immediate task is to find a place of safety.

—Isaac Rosengarten, the Jewish Forum

IN 1938, as the sun set on the European continent for the Jewish People, and the darkness of impending war and virulent anti-Semitism encroached, a bold initiative was put forth in the hopeful pages of the Jewish Forum. It wasn’t just an ordinary rescue mission but a daring proposition to purchase or lease the region known as Baja California (“Lower California,” a Mexican territory south of the US state of California). The aim was to transform its vast wilderness into a sanctuary, a potential Jewish homeland where refugees could seek solace and security.

This ambitious plan was not hatched in isolation. In an era when Jewish activists desperately searched for safe havens, similar proposals had been envisaged for locations as diverse as Madagascar, Asiatic Russia, and the Kimberley region of Western Australia. Each plan offered a glimmer of hope against the backdrop of closed doors and limited options for Jewish emigrants facing imminent peril.

This Baja California project was the brainchild of Dr. George Richter, a member of the Committee of One Hundred, who first presented the plan in the Jewish Forum after visiting the arid landscapes of the area. Financing such a dream would require an international effort, possibly involving the kind of substantial backing that had supported American ventures like the purchase of Alaska. To kick off the initiative, Jewish Forum editor Isaac Rosengarten formed a group called Selah Inc. to raise funds and awareness.

In PR materials and countless articles, Rosengarten and others proposed developing Baja’s potential in agriculture, mining, and fisheries, to sustain the community. The pitch was poetic. In one editorial, Rosengarten wrote:

Cast your eye westward in the direction of California. Follow its coastline southward and note a peninsula about 800 miles long and from 50 to 100 miles wide. It is called Lower California. It is bounded on the west by the Pacific, on the east by the Gulf of California, on the north by the United States. Geologically and geographically, it is an extension of California.

In its northeastern part is the delta of the great Colorado River, a wonderfully fertile region.

The climate is healthy, the land is rich in mineral resources, fine agricultural regions, fisheries, game, and bays. Anything can be grown there. It produces wheat, barley, beans, corn, nuts, peaches, apricots, grapes, lemons, oranges, pears, apples, quinces, cherries, pomegranates, figs, dates, olive oil, honey, sugar cane, cotton, and every variety of garden vegetable.

Dig in its mines and you will find gold, silver, copper, lead, zinc, iron, manganese, mica, salt, sulphur, magnesite, turquoise, tourmaline, onyx, and marble.

Yes, it has all these things, but it would not be a simple matter to colonize it. Was it easy for the American pioneers to conquer the wilderness? Look at what the Jews have accomplished in Palestine within a short space of time, surrounded by numerous difficulties.

But it wasn’t long before the establishment came out in opposition to the plan. For one, Selah Inc. was not even negotiating for the land with the Mexican government (which had jurisdiction over Baja California), choosing instead to petition President Roosevelt for help.

Because many immigrant Jews could not write a letter in English, pre-printed forms were distributed for American Jews to sign and send off to the White House. The letters stated:

To the President of the United States of America, Washington, D. C.,

In view of the traditionally helpful attitude of America to oppressed peoples of all lands and of precedents established, we, the undersigned, citizens of the United States of America, respectfully petition you to intercede with the Mexican Government on behalf of our Jewish fellowmen in lands of oppression, where eight million (in Germany, Poland, Roumania, Austria, Hungary, and other countries) are doomed.

While the greatest hope of Israel will ever be a return to the Holy Land of Israel, possibilities for a sufficiently large Jewish migration are limited.

Since entry into other countries is either too greatly restricted or not feasible, and in view of the possibility of a large Jewish immigration into territory bordering on that of the United States of America, six times the size of Palestine, and with a present population of less than 100,000, to which our country can offer its protecting wing in harmony with the Government of Mexico, we plead for an arrangement for a home of refuge in Lower California to be ultimately incorporated as a Jewish State within the federal system of Mexico yet possessing its own local autonomy, its integrity to be guaranteed by the Pan-American nations.

The plan for Lower California faced additional criticism, including from within the Jewish community itself. Der Tog editor Samuel Margoshes, who opposed the plan, viewed it as a distraction from the more pressing needs to aid European Jewry and to focus on establishing a homeland in Palestine.

Yet as the Jewish Forum gathered signatures for its petition and sought to sway the minds of statesmen, some formidable obstacles emerged. In addition to the fact that no major philanthropist or organization got behind the concept, the Mexican government took a firm stance against it. Despite entreaties and promises of a Pan-American endorsement, Mexico’s concerns over sovereignty and the political implications proved too significant for proponents to overcome.

The vision for Baja California as a Jewish refuge, with Tijuana as its Jerusalem, remained just that — a vision. As World War II ensued, and the Holocaust unfolded, the necessity for such a sancutary became tragically apparent.

Rav Kook and the Mexican President

The Inquisition remained active as late as 1820 in New Spain, as Mexico was called before it gained full independence. Thus, Mexico never had more than a tiny Jewish population (the 1900 census counted just 134 Jews) until around the time of World War I.

In October 1924, Rav Avraham Yitzchok HaKohein Kook and several other leading rabbis were attending a convention in Manhattan when they learned that Mexican president-elect General Plutarco Elías Calles was in town. The delegation arranged to meet with him and discussed the plight of the Mexican Jews. After receiving a blessing from Rav Kook, Calles assured the group that Mexico would not discriminate and that they could depend upon his friendliness to the Jewish People.

They Called Him Ike

Isaac Rosengarten (1886–1961) was born in Lithuania and came to American as a young boy. He remained a bachelor and worked as the English principal at the Eitz Chaim yeshivah in Boro Park before becoming editor of the Jewish Forum, a job he would hold for the next 44 years. A close friend of many leading figures in American Orthodoxy, he helped found an important organization (which may hold the record for the longest name of any nonprofit in history) called “the League for Safeguarding the Fixity of the Sabbath Against Possible Encroachment by Calendar Reform.”

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 1007)

Oops! We could not locate your form.