Louder than Words

You can do remarkable things with silence.

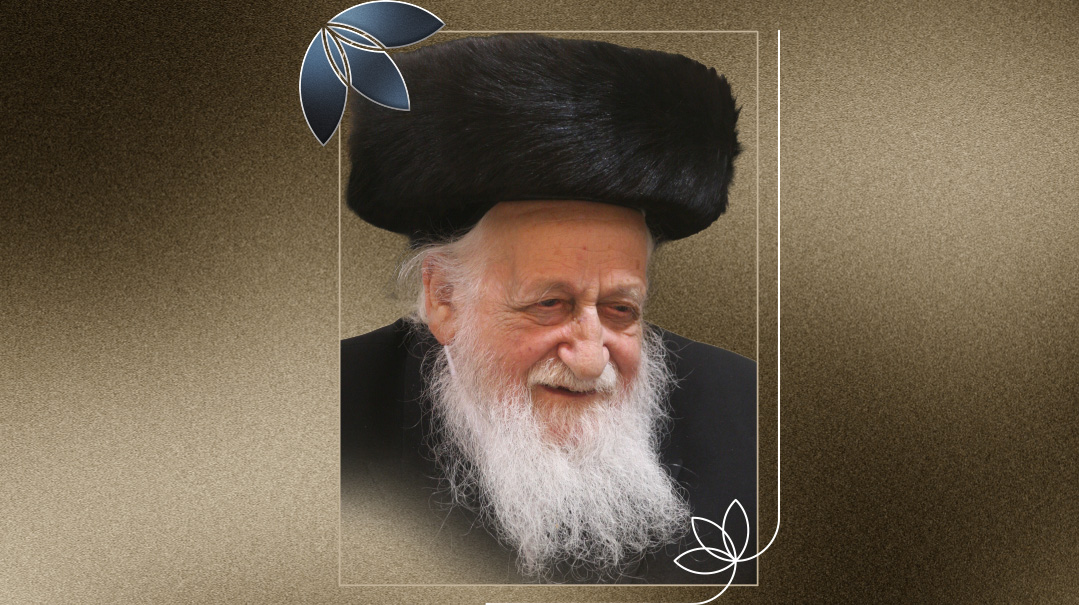

Imagine a rebbe who leads with silence, using it as a tool to draw forth, to demand, to teach, a silence that allows him to hear the dreams of those around him.

In a small gazebo, I found a quiet rebbe, leading a quiet chassidus in a way that calls to mind those paintings, the ones where the entire town of wooden huts is visible in the background, as a small huddle of Jews gather after Kiddush Levanah or Tashlich, their faces exhilarated, worn, alive.

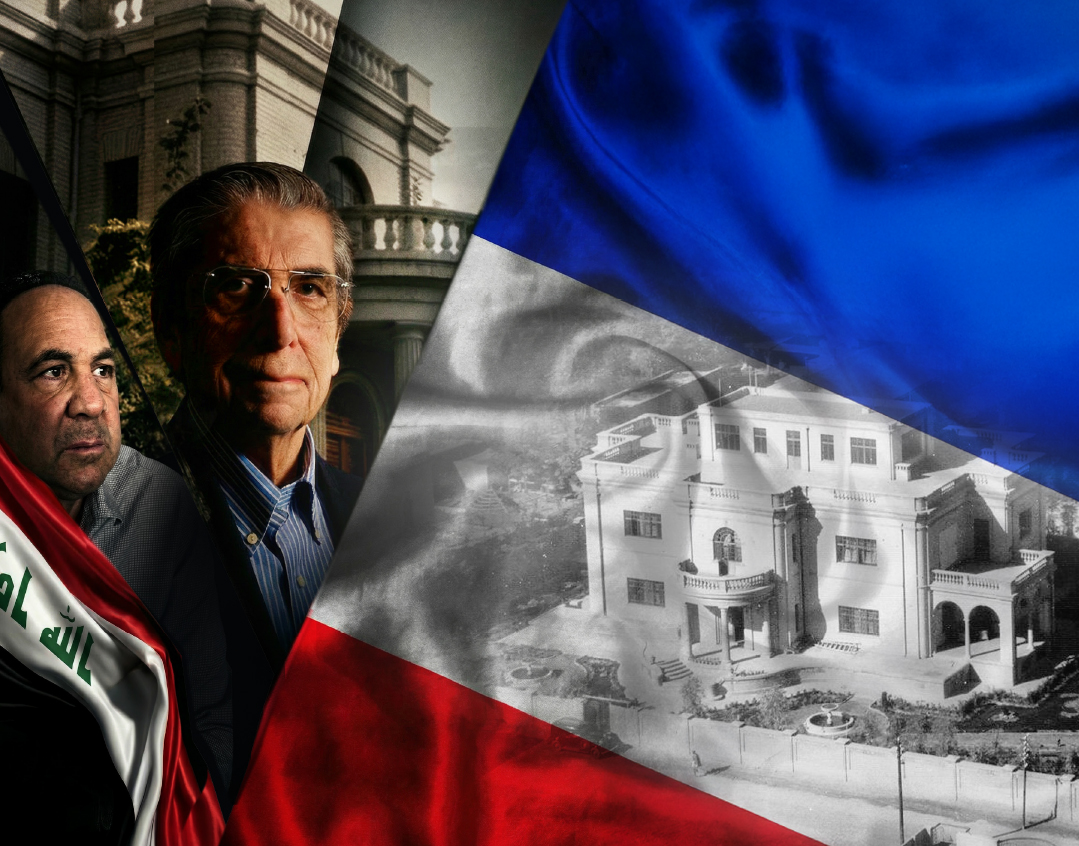

The backdrop to the present scenic picture is the current of expectation that runs deep here. It’s the imprint and legacy of the community’s founder, the Shefa Chaim — Rav Yekusiel Yehuda Halberstam of Sanz-Klausenberg ztz”l, father-in-law of this rebbe of hushed tones: Rav Shlomo Goldman of Zvhil-Sanz.

On the Porch

The soundtrack at Machane Divrei Chaim in Kauneonga Lake, summer home of the Sanz-Zvhil community of Union City, New Jersey, is one of voices raised in learning in the Klausenberger style. The beis medrash and several adjoining rooms, the porches and picnic tables, are filled with shiurim and chavrusas on the Monday morning when I arrive.

I am directed to the “Rebbe’s tent,” the gazebo in the shade of a tree where a bottle of water, a glass, and a pile of seforim sit expectantly — but the Rebbe isn’t there.

This rebbe, it appears, is blessedly free of the coterie of gabbaim and handlers; free enough that I finally find him sitting on a porch, having spontaneously joined a chavrusashaft with two kollel yungeleit, who speak with him in learning.

He smiles in greeting and together, we walk down the path towards his gazebo, smack in the center of the camp and bungalow colony that service his kehillah and yeshivah.

There is a gentle breeze as the Rebbe welcomes me to sit down in the tent in which he spends much of his summer, sitting and learning.

He appreciates my comment regarding the yeshivah-like atmosphere around the camp, and he reflects on his shver’s unique relationship with the kehillah of Union City. The Klausenberger Rebbe, who moved to Williamsburg in 1947 after surviving the Holocaust and caring for survivors in the DP camps, finally fulfilled his dream of settling in Eretz Yisrael in 1960, in Netanya’s Kiryat Sanz section, which he established. In 1968 he returned to the US to open a yeshivah and community in Union City, and from then until his passing in 1994, he split his time between the two centers of the chassidus.

The chassidus the Klausenberger Rebbe rebuilt numbers thousands of families and has centers across the globe; with major hubs in Netanya and Brooklyn, led by his two sons. Union City is part of the network, and it was here that the Rebbe had the luxury of living and breathing the yeshivah.

“Wherever my shver was, the yeshivah was always on his mind, but there were other things as well. He was rebuilding lives, helping individuals. He established a new neighborhood, Kiryat Sanz, a major hospital, Laniado — he carried a huge burden. But here, in Union City, there isn’t much going on outside the yeshivah, so that’s what you feel.”

The Zvhil-Sanzer Rebbe was born in Meah Shearim, a child of Batei Ungarin; the first time he saw a telephone was when he was 18 years old and a talmid of his future father-in-law at the Sanzer yeshivah in Netanya.

When it came time to find suitable husbands for his daughters, the Klausenberger Rebbe was looking for talmidei chachamim, and he set his eyes on the son of the Zvhiller Rebbe.

With a shrug and gentle smile, the Zvhil-Sanzer Rebbe confides that, as the oldest son-in-law, he was heavily involved in the shidduchim for the other daughters. “My shver wanted talmidei chachamim, even at the expense of family background. I once argued that Chazal put emphasis on yichus and perhaps he should be considering scions of rebbishe homes. The Shver said, ‘Okay, fine, for yichus I’m ready to give away five hundred blatt — but not more. The Gemara says that giving a daughter to an am ha’aretz is like giving her to a lion.’ ”

After years in kollel, the new son-in-law joined the yeshivah staff as a maggid shiur; when the Shefa Chaim established the Union City yeshivah, it was his son-in-law whom he sent first to build it up. Later, the Rebbe himself came and joined his married couple, the two families living alongside each other in the yeshivah building.

Rebbetzin Leah, the Shefa Chaim’s eldest child, had a special relationship with her father; as a single girl, she was one of the leading teachers in the Klausenberg girls’ school, developing her lessons along with her father, the Rebbe. Together, they authored the work Derech Chaim, an overview of chassidus, its ideals and its relevance, written specifically for women.

After her marriage, her husband merited the same closeness. Older chassidim remember the seemingly perpetual chavrusashaft between the Rebbe and his beloved son-in-law, and recall the era when they learned together as the best years of the elderly rebbe’s life.

Late one night, the Zvhil-Sanz Rebbe tells me, he and his shver were poring over a difficult sugya when the Klausenberger Rebbe remembered a relevant teshuvah. He stood up and went to locate the source, but even as he looked through his library, he couldn’t find it. The hour grew late, and eventually, the son-in-law went to sleep.

Deep into the night, there was a knock on his door. “Ich hub getruffen, I found it,” an exhilarated Klausenberger Rebbe called out into his son-in-law’s room.

The Zvhil-Sanz Rebbe smiles at a memory. During those years, another prominent rebbe came to visit the Klausenberger Rebbe, who received him in his “seforim shtib” study at his apartment, which was part of the yeshivah.

“Where do you live?” asked the visiting rebbe, certain that his host had a more impressive home than the large study with its overflowing shelves and yeshivah-issue furniture.

“Here,” said the Klausenberger proudly, “this is my home.”

The guest rebbe was clearly astonished.

Common Ground

Among the many paths into which the Baal Shem Tov’s legacy diverged — different hues and shades of the same picture — Sanz and Zvhil are not a natural overlap. The glorious fervor and fiery passion of Sanz aren’t a natural complement the humility and utter simplicity of Zvhil. Sanz, as embodied by the Shefa Chaim of Sanz-Klausenberg, was all about Torah — hasmadah, knowledge, retention. Zvhil was about pashtus, anonymity, and secrecy.

Rav Shloim’ke Zvhiller left Zvhil, Ukraine, for Jerusalem in 1926, in order to escape the exposure generated by miracles he’d performed back home. He was determined to live as a private citizen.

Rav Yekusiel Yehuda Halberstam survived the horrors of the Holocaust and arrived in the United States determined to build, teach, expand, and inspire — a very public citizen.

Reb Shloim’ke’s son, Rav Gedalia Moshe, was a tzaddik who lived in obscurity and was buried in obscurity — in a tiny cemetery not far from the Machane Yehuda shuk, as wartime conditions made it impossible for his family to reach Har Hazeisim. His son Reb Mordche, the Zvhiler Rebbe until his passing in 1981, maintained the family tradition.

How does one fuse these two paths into one?

Rav Shlomo Goldman of Sanz-Zvhil answers the question with a memory dating back to the years when he was a chassan in the Sanzer yeshivah, engaged to the Rebbe’s daughter — and his father Rav Mordche was coming on a visit from Yerushalayim.

The bochurim were gathered around in anticipation of the visit of the Rebbe’s new mechutan, expecting an entourage: they were surprised when the Zvhiller Rebbe alighted from a bus, like a common passenger.

“That my father took a bus from Yerushalayim to Netanya makes sense — he wasn’t wealthy, and had no driver. But it never even entered his mind to take a taxi from the central bus station to Kiryat Sanz. He never considered that it might add to his prestige. It meant nothing to him.

“In fact,” the Rebbe smiles at the memory, “when I became a chassan with the daughter of the Klausenberger Rebbe, my father didn’t care that he was a big rebbe, a big meyuchas, he wasn’t impressed by the large chassidus. What meant the most to my father was the fact that my shver was a big talmid chacham.”

And that’s the answer. Zvhil and Klausenberg meet at the shtender.

Driven for Torah

The Rebbe’s relationship with his father-in-law started as that of a talmid and his rebbi.

“My shver had talmidim, not just chassidim,” the Zvhil-Sanz Rebbe says. “He sent out more dayanim, rabbanim, and maggidei shiur than almost any other yeshivah, because he was driven to make talmidei chachamim. He would call in each bochur and ask for a reckoning of their daily schedule, trying to figure out how much learning they could do.”

Once, a bochur asked the Shefa Chaim, “How much does the Rebbe think I should sleep at night?”

“No,” the Rebbe replied. “You tell me how much sleep you need at night and then we’ll figure out how much you should be learning. And you know what? I’ll throw in an extra half hour of sleep too, but the rest of the time is for learning.”

The Rebbe wanted his bochurim to be fully engaged in the rhythms of a chassidic lifestyle but not on the cheshbon of being talmidei chachamim. “If he saw a bochur at the tish, he would say, ‘Go learn, you should be in the beis medrash,’ but at the same time, if there were bochurim who never came to tish, he would ask them where they’d been. He wanted a balance,” his son-in-law explains.

“Nothing, but nothing, made him happier than seeing a bochur learning early in the morning or late at night. He could break out in dance from that, from a good kushya, a siyum masechta.”

It was the beis medrash that energized him, the privilege of davening to Hashem that gave him life.

As a young man, the Zvhil-Sanz Rebbe inherited a respectable sum of money and his shver, the Shefa Chaim, advised him to invest in diamonds. He followed his shver’s suggestion — but just days later, the diamond market collapsed, and his investment suffered.

The Klausenberger Rebbe felt terrible about what happened and one night, he looked at this son-in-law in distress and said, “Nu, what do you say to my moifes?”

The Zvhiller-Sanz Rebbe perceived his shver’s anguish. “I’ve seen much bigger moifsim from the shver,” he said, “such as when the shver comes into Maariv at midnight looking drained, worn out from a long day of helping Yidden and raising money and meeting people and toiling in learning and it appears that the shver is too exhausted to move a muscle. Then, when the shver says ‘Burech Atuh Hashem…” and starts davening, he suddenly looks as relaxed as if he just arrived home from vacation. That’s a moifes!”

No Talking

In his every word, there are notes of the Zvhiller-Sanzer Rebbe’s background, the flavor of Yerushalmi locals gathered outside the Meah Shearim shtieblach looking for a tzenter, the unpretentiousness and gentle humor that peppers their conversation so conspicuous in his.

When Reb Shloim’ke Zvhiller was looking to escape the pomp and ceremony of formal leadership, he found the best place on earth, the neighborhood where simplicity is treasured above all. In reflecting on his Zvhiller heritage, the Rebbe shares a fascinating bit of history. His father, Reb Mordche, accompanied the zeide Reb Shloim’ke on the boat from Ukraine to Yerushalayim. Departing — really, escaping — a community that revered him as a miracle-worker and ascribed him supernatural powers, the saintly Reb Shloim’ke expressed the hope that no one would talk about his greatness in Yerushalayim, as they had back home.

“My father would never tell stories about his father even after Reb Shloim’ke’s passing, out of deference to that comment. The Zeide had said not to talk about him.”

Still, Reb Shloim’ke couldn’t escape a following; lines of locals lined up to offer names in need of a yeshuah before Reb Shloim’ke immersed himself in the mikveh. Even the most hardened residents came to accept that the newcomer’s prayers and blessings carried weight in heaven. The name of Zvhil remained sacred, perhaps even more than before.

The middle generation, Rav Gedalia Moshe, succeeded his father as Zvhiller Rebbe, but he passed away just five years later, in 1950. Har Hazeisim was off limits and the Rebbe was laid to rest in the Sheik Badr Cemetery in the center of the Jerusalem (in the shadow of the current Knesset building). In recent years, the burial site has become a magnet for all sorts of people, tales of salvation running like the streams of wax from the candles that line the nearby fence.

The Rebbe nods when I ask about the kever. “We don’t have a particular mesorah in the family about the new segulah of davening there on a Monday, Thursday, and the following Monday, but I can tell you that the stories don’t come as a surprise. There were decades during which the kever was largely unnoticed, but whenever we, in the family, would visit, we would see lit candles there. Apparently, the tzaddikei Yerushalayim knew all about it.”

In fact, when Rav Aharon of Belz was laying the cornerstone for the Belzer yeshivah on Agrippas Street in the 1950s, he looked off into the distance and smiled, satisfied. It seemed peculiar, for the Rebbe was looking at the center of the city, site of the government headquarters.

“The tzaddik of Zvhil is nearby,” the Rebbe explained, “it’s good for the yeshivah.”

Eyes that Speak

The Zvhil-Sanzer Rebbe of Union City maintains a familial mesorah of another sort as well. Reb Shloim’ke came to Yerushalayim to escape the position of rebbe: rather than building his own chassidus, he was a rebbe to everyone else’s chassidim. The good Jews of Jerusalem appreciated the saint in their midst, as petitioners flocked to him for blessing and advice.

His great-grandson, the Rebbe of Union City, fills a similar role. Most of the kehillah is connected with Sanz, with Klausenberg, yet they live in his shadow, confident in his presence and inspiration. Many years ago, Rav Shmuel Alexander Unsdorfer, a respected rav in the Klausenberg community (and father-in-law of the present Sanzer Rebbe in Netanya) contemplated the young Zvhiller Rebbe and said, “A time will come when m’vet brechen tiren — they will break down doors — to get into this rebbe.”

Given the aura of tranquility that hovers over this rebbe, it’s difficult to imagine breaking doors and pushing bodies, but Rav Unsdorfer’s image of streams of petitioners is being realized. The chassidim who pass through the Rebbe’s room arrive from all directions, from Williamsburg and Lakewood and Brooklyn and Monsey, bearing all sorts of problems and questions. The Rebbe melds the practical wisdom of old Jerusalem with far-reaching vision; he is both good friend and sagacious guide. Once a year, on the yahrtzeit of the zeide Reb Shloim’ke, he leads a tish in Boro Park and during the Aseres Yemei Teshuvah, the Rebbe visits Lakewood; wherever he goes, even without sophisticated PR and promotion, lines automatically form. As by his revered zeides, the people just know.

Within the wider Sanz-Klausenberg, he is revered and respected by both rebbes — his brothers-in-law — and their chassidim. His nephews and nieces are steady visitors at his court, seeking brachos and advice.

When Rav Mordche of Zvhil passed away in 1981, the chassidim urged his son in Union City to return to Yerushalayim and assume the mantle, but his father-in-law asked him to remain in Union City; the young Rebbe deferred to his shver, and the family has never forgotten his devotion. (His brother Rav Avraham, who passed away in 2009, became the Rebbe in Yerushalayim.)

Perhaps the nicest feature of his chassidus: Visit the beis medrash in Union City almost any morning or afternoon, and you’ll find the Rebbe — a towering talmid chacham — walking between benches, speaking in learning with yungeleit or bochurim.

Prominent Sanzer philanthropist Reb Mechel Rosenberg recalls taking the visiting Zvhiller Rebbe to meet Montreal’s legendary rav, Rav Pinchas Hirschprung, who was a celebrated baki in Shas. In conversation, the name of the Amora, Rav Chana Bagdesa’a, came up, and Rav Hirschprung quoted Rashi, who says the name was a reference to the Amora’s hometown of Baghdad. The young Rebbe mentioned that there is another reason given, also in Rashi, but Rav Hirschprung disagreed. The Rebbe indicated the first pshat in Rashi (Yevamos 67), that it refers to the Amora’s proficiency in aggadah.

Twenty years later, when the Rebbe was back in Montreal, Reb Mechel again took him to visit the Rav. “Does the Rav know the Rebbe?” he asked Rav Hirschprung.

“Know him?” the Rav exclaimed, “How can I forget him, he chapped me on a Rashi!”

The Rebbe has two defining features, immediately apparent. One is his eyes. Some people call them “Zvhille oigen,” eyes unique to the dynasty: large, probing, knowing — a strange mix of good humor and sorrow.

The Shefa Chaim is known to have said that his son-in-law has “heilige oigen.”

The Rebbe’s other feature isn’t visible, but discernible just the same. Close to twenty years ago, a severe illness claimed his voice box. He chooses his words carefully and isn’t always audible; it makes his influence all the more remarkable.

It’s as if he uses his eyes to speak as well.

Behind the Times

The people closest to him, the chassidim of Union City, reflect some of that quiet.

A Union City chassid tells me about shopping in a popular Brooklyn men’s clothing shop, looking for a new rekel. The salesman showed him various styles, asking if he preferred a garment that extends to the knees or a longer, more-fashionable look. The customer looked blank, and the salesman asked him where he was from.

“Union City.”

“Ah, forget it,” the salesman waved his hand, “then it makes no difference if it’s in style.”

When the Klausenberger Rebbe established the community, there were approximately seventy families. During the last half a century since the community was founded, people have come and gone, but the numbers have essentially stayed the same.

Locals feel that it’s a special siyata d’Shmaya that has kept the kehillah small, even intimate. Life in Union City, with its modest two-family homes and relatively quiet streets, is still very much in line with the Klausenberger Rebbe’s vision: a community big enough to be vibrant — with a full spectrum of chinuch mosdos as well as a grocery store, Hatzolah, and Chaverim — but small enough to have remained pure, with its single central beis medrash. Along with the Rebbe, there is a dayan, Rav Shaul Yehuda Prizant, also a son-in-law of the Shefa Chaim. Approximately half the men learn in the kollel or work in one of the chinuch institutions, while the remainder commute to workplaces in Manhattan and elsewhere.

By his own admission, the Rebbe feels unqualified to discuss some of the current issues facing the wider chassidic community. “We have a small town, a simple place. Baruch Hashem, many of these problems haven’t reached us yet, and I hope they never will. We’re behind the times.”

When the Klausenberger Rebbe established the kehillah in Union City, his heart and mind were on Eretz Yisrael, where he’d founded Kiryat Sanz a few short years earlier. Chassidim feel that some of the ahavas ha’Aretz that fueled the Rebbe then came to rest on Union City, that it carries the fragrance of Eretz Yisrael.

Meshulachim certainly seem to think so; tzedakah collectors visiting America like to break up the Brooklyn-Lakewood route with a stop in Union City. There are more populous neighborhoods, and certainly wealthier neighborhoods, but in Union City, they can have a cup of coffee with undertones of “back home.”

The people are nice too. Union City, on the New Jersey end of the Lincoln Tunnel, ends up absorbing last-minute Shabbos guests on short Friday afternoons, when heavy traffic or difficult weather conditions make reaching Lakewood impossible. They’re always ready, the community springing into action like a well-oiled machine, spreading its arms wide —

To all sorts of Jews. In a recent memoir in the New Jersey Jewish Link, the daughter of a former local rabbi reflects about how

We were fortunate to have the Klausenberger Rebbe take an interest in Union City… Because of the chassidim, Yiddishkeit is once again thriving in Union City, after a lull… I have only admiration for a warm, caring, genuine community of people who deserve all the hakaras hatov in the world. Today, it is obvious that the chassidic community lives amicably alongside the dominant Cuban population in Union City.

By the way, anyone who wants to catch a minyan traveling via the Lincoln Tunnel to and from New York City is welcome to daven with the community. They are the most gracious, friendly, sincere community, welcoming all….

Starting Over

The Rebbe and his rebbetzin are not the only illustrious residents of Union City; the kehillah is graced by the presence of the “Alte Rebbetzin,” the Shefa Chaim’s second wife and mother of his children. Within the Sanz-Klausenberg community, she is known as the “Babbe” of the chassidus — but the “Mamme” of the Union City kehillah. With the graciousness that defines their relationship, the Rebbe suggests that I pay a visit to his shvigger, in a nearby bungalow.

Rebbetzin Chaya Nechama was the wife of one of the great rebbes of the generation, mother of two leading contemporary rebbes, matriarch of a family filled with rabbanim and roshei yeshivah, witness to epic destruction and a partner in the spectacular rebirth. She’s seen it all, but she has the characteristic — unique to aristocracy — of focusing on others.

She lists off various family members of mine that she knows, asking about my wife and children as she welcomes me to sit on the porch.

Only when she seems assured that I am genuinely interested in hearing does she start reminiscing. Though she grew up in a home of rabbinic royalty, she wasn’t exposed to the world of chassidim and rebbes.

“My father wasn’t chassidish, but he had a chassidishe neshamah.” The Rebbetzin, daughter of the Nitra Rav, Rav Shmuel Dovid Ungar, remembers how her father “had certain sensitivities. He didn’t like when we wore the color red. We wore thicker stockings than any of the other local girls.”

When Rav Shmuel Dovid Ungar was asked to serve as rav in Nitra, Slovakia, he accepted, despite the fact that he was leaving a vibrant kehillah in Tirnau. He explained that his heart told him a yeshivah in Nitra would endure through the dark years that were approaching. “When there are no more yeshivos in Slovakia, they will still be learning Torah in Nitra,” he prophesized. He moved to Nitra, establishing a yeshivah which drew talmidim from across Hungary, Romania, and Germany.

The Nitra Rav’s son-in-law, Rav Michoel Ber Weissmandl, joined him in leading the yeshivah; as the Nazis came to power and a willing Slovakian government handed over its Jews, yeshivos across the country were shut down. Rav Michoel Ber, mixing diplomacy and daring to negotiate with officials to save as many Jews as possible, received permission for the yeshivah to remain open. The Nitra Yeshiva had the unique architectural feature of secret hiding places underneath the bimah and in the walls of the beis medrash in case of Nazi inspections. Through it all, the Nitra Rav maintained dignity and order, delivering shiurim and conducting bechinos as if the world wasn’t on fire beyond the yeshivah walls.

The yeshivah was ultimately closed in September 1944, a week before the last Jew in Nitra was deported; the Rav and one of his sons went into hiding, joining a group of partisans in the forest, while his daughter Chaya Nechama was deported to Auschwitz.

“I have no number,” the Rebbetzin shrugs, “but believe me, I have plenty of reminders.”

The Nitra Rav eventually died in the woods; before he did, he recited Vidui and gave his son specific instructions regarding burial. He was laid to rest in the forest, but after the war, he was reinterred next to his own father in Pishtian, near Verbau.

“My father’s yahrtzeit was the 9th of Adar, but the second yahrtzeit, the day he was finally buried in Pishtian, was the 9th of Tammuz — that’s the same yahrtzeit as my husband, the Rebbe,” the Rebbetzin informs me.

The two men — the Nitra Rav and the Klausenberger Rebbe, one losing his life, the other losing everything but his life — never met; the Klausenberger Rebbe eventually reached America with a band of ragged survivors around him, his own wife and ten children murdered. His eleventh child, a son, had survived, but succumbed to illness at the very end of the war.

Rav Sholom Moshe Ungar, who’d buried his father in the forests of Slovakia, arrived in America as well, where he was appointed the new Nitra Rav. Together with his brother-in-law, Rav Michoel Ber, they reestablished the Nitra Yeshiva in Sommerville, New York. (One year later, the Nitra Yeshiva would move to Mount Kisco, where it remains until today.) Two leaves remaining on a tree stripped bare: two yeshivos holding on to the tree of prewar life, Sheiris Hapleita led by the Klausenberger Rebbe, and Nitra in Sommerville. Rav Michoel Ber suggested the shidduch between the widowed Rebbe and the orphaned Chaya Nechama, who’d never been married. He assured his sister-in-law that the prospective chassan, although a chassid, was someone who would have made her deceased father proud.

The chasunah was held on Erev Shabbos, the 6th of Elul, 1947, in Sommerville.

The chassan — the holy Klausenberger Rebbe — prepared for the chasunah reciting the traditional Vidui, wrapped in a tallis and crying profusely. Chassidim and talmidim waited patiently, eager to receive his brachah before the chuppah, seeing it as a time of particular Divine favor, but the Rebbe seemed to be somewhere else.

It was Erev Shabbos and there was no time for kvittlach, the gabbai announced, calling the Rebbe to come forth for the chuppah.

“Rebbe,” a woman called out, “we’re all waiting for your brachos, yet you have been davening on our cheshbon. Do you really need so much teshuvah? Have rachmanus, Rebbe, and bentsh us…”

The tears flowed, the compassionate Rebbe receiving each and every petitioner with their kvittlach before going to the chuppah, still wrapped in his tallis.

Following the chuppah, the guests began Kabbalas Shabbos, led by the chassan. When the Rebbe reached the words “l’hagid baboker chasdecha, ve’emunascha baleilos,” he stopped, repeating them again and again, his face aflame.

After the longest night, morning had arrived.

The Children Came First

“The first thing my husband did was borrow money to build,” the Rebbetzin recalls with an indulgent smile. “We bought an apartment in Williamsburg, which became a beis medrash. From that moment on, he never stopped, borrowing and building, borrowing and building.”

A rebbe isn’t the same thing as a rav, and the Klausenberger understood that his wife had been raised in a certain fashion. Several times a week, he prepared coffee for his new rebbetzin, sitting down to join her — understanding where she came from.

“He was a prince of a man, a husband and father.”

An early talmid recalls going to speak with the Rebbe one sweltering Friday afternoon. The Rebbe sat at the table, immersed in learning, perspiring profusely from the blistering heat. The resourceful talmid immediately searched the apartment and found an electric fan in the kitchen, which — with the Rebbetzin’s enthusiastic permission — he unplugged and brought to his rebbe’s room.

The Rebbe was irate. “You took the fan from the kitchen? Where the Rebbetzin is standing on her feet and preparing ma’achalei Shabbos?” He looked at the talmid with obvious disappointment. “I don’t understand how you can consider getting married until you understand what Chazal say, that one must honor his wife more than he honors himself, yoser migufo.”

Later, as the family grew, the Rebbe — who was so many things to so many people, rebbe, rosh yeshivah, builder, and counselor — made his family a priority. “Each night,” says the Rebbetzin, “he would circulate among the children, adjusting blankets and pillows.”

One night, the Rebbetzin remembers, the Rebbe woke her up in a panic. “Sureh Esther isn’t in her bed!” he exclaimed. The Rebbetzin explained that their daughter was spending the night studying at a friend’s house. But rather than calm down, the Rebbe grew more agitated. “That means I woke you for no reason,” he said in dismay.

“He was horrified, as if he’d taken money or something that was not his. He’d taken a moment of my sleep!”

The Rebbe rarely discussed the family he’d lost, but he would tell his children stories of survival.

“He once took the children for a walk and showed them the trees, filled with leaves. He told them how he’d been shot at in the death camps, but refused to go the infirmary because he knew they would kill him. Instead, he’d used a leaf to stop the bleeding and a tied a branch around his arm to keep the leaf in place, promising that if he would survive, he would found a hospital where patients would be treated with dignity.” It was a promise he would fulfill, establishing and leading Laniado Hospital in Netanya.

The years passed. The broken chassidim became whole, building families, generations. The chassidus grew, with branches in America, Israel, Europe. The Rebbe became an international leader, revered for his learning and guidance.

In his travels between Eretz Yisrael and America, one thing was constant: he never returned home without a gift for the Rebbetzin.

And he never lost sight of his prime role, a father to his children.

According to legend, the Rebbe — who was in his forties when he remarried — had promised his young rebbetzin that he would personally preside over the marriage of all their children. When the youngest of his seven children, Rebbetzin Sureh Esther, got married, the Rebbe was aged and infirm. He was present, but unable to officiate; it was several years since he’d spoken in public.

It was announced that the Rebbe’s eldest son, Rav Tzvi Elimelech — today the Sanzer Rebbe of Netanya — would serve as mesader kiddushin, but the kallah had other ideas. “My father promised that he would marry us off, and I’m not going to the chuppah until he comes forward.”

Minutes passed, then hours. The crowd was asked to join in Tehillim. There was a commotion, then silence, then confusion — and then the familiar raspy voice, silent for too long, rang out with Burech Atuh…

The Rebbetzin smiles at the memory. “It meant a lot to him. His children meant a lot to him.”

Before leaving, I ask for a brachah for a gut yohr, which she offers with great warmth — and a disclaimer. “I’m not a professional rebbetzin. I never understood kissing hands and bringing me kvittlach. I’m a rav’s daughter.”

All That Goodness

Walking back to my car, I pass the small gazebo where her son-in-law the Zvhiller Rebbe learns on — the eternal flame, the ner tamid, of this community.

He extends his hand in farewell, offering a final insight.

“What made my shver special was his middas hahatavah, his desire to do good for other Yidden, to benefit them. At a meeting for Laniado Hospital, a professor mentioned that in some European hospitals, they were using a thinner type of needle, which minimized pain. The Rebbe asked why they couldn’t use such needles in Laniado, and the hospital executives explained that the cost for each needle was prohibitive.

“Too much? No amount of money is too much if it will spare a Yid suffering,” the Rebbe said.

“My shver was the most giving person — and all that hatavah, all that generosity, was poured into creating talmidei chachamim. He felt that the biggest chesed he could do was to get the bochurim to learn more, to learn better, to create a new generation of talmidei chachamim.”

A young boy, peyos blowing carefree in the breeze, rides a green bicycle down the path near the Rebbe’s tent. He looks inside and locks eyes with the Rebbe.

“Nu,” the Rebbe says, “when are you coming to be farherred? It’s time already, you haven’t come in a few days!”

The boy drops his bike with a clatter and hurries in, his smile stretching from ear to ear.

The Rebbe leans across the table to stroke his cheek, a gesture stronger than any embrace, more eloquent than any expression.

“My shver felt,” the Rebbe looks back at me, “that there was nothing more important than giving people Torah. It’s the ultimate goodness. It’s giving people life.”

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 578)

Oops! We could not locate your form.