Looking Forward Means Looking Back

| June 9, 2024Me? I thought, hesitant. Who am I to write a book about the Tannaim and Amoraim?

I’ve always been intrigued by history, but my passion for researching and writing Jewish history manifested only about ten years ago, when I was in kollel in Eretz Yisrael. I was compiling brief biographical notes about the Tannaim and Amoraim, both because it was fun — I enjoy this type of stuff — and because I wanted to create biographical sketches that I could look back at. Mainly, I was curious to figure out the rebbi-talmid relationships, so I wanted to put to paper the basic concepts of who lived where and when, along with other biographical information, so I could work my way through it.

One afternoon during bein hasedorim, as I was diligently typing away on my laptop while peering back and forth between a Gemara and the screen, a close friend glanced over my shoulder and started reading. He was fascinated.

“Why don’t you write a book?” he asked. “No one knows this stuff.”

Me? I thought, hesitant. Who am I to write a book about the Tannaim and Amoraim?

But my friend is really persuasive, and he soon had me convinced.

For the next year, I gathered information from a lot of sources: Seder Hadoros, Sefer Yuchsin, Koreh Hadoros, the Chida in Shem Hagedolim, Iggeres Rabbeinu Sherira Gaon, Seder Olam, Gemara Bavli and Yerushalmi, Rashi, Tosafos, the Rambam, the Meiri, Acharonim like the Yaavetz, Maharatz Chayes, Toldos Tannaim v’Amoraim. I researched the lives of the primary Tannaim and Amoraim: Ezra Hasofer, Hillel, Shammai, Rabi Yehuda Hanasi, Rav, Shmuel, Rabi Yochanan, Reish Lakish, Abaye, Rava, Rav Ashi, and many more.

It took three years of research, writing, and editing, and in September 2019, Judaica Press published The Tannaim and Amoraim.

My brief foray in a career of writing, I assumed, and I resumed my full-time kollel schedule. People would ask, “So what’s next, a book on the Rishonim?” and I’d smile, appreciative of the feedback, but I didn’t think about it seriously.

One day two years later, my phone rang. By then I’d joined the community kollel in Cincinnati, Ohio, where we still live.

“Nosson, would you consider writing a book on the Rishonim?” Judaica Press’s managing editor Nachum Shapiro asked.

Wow — what?

I was excited about the prospect, but I was also taken by surprise — and somewhat overwhelmed by the fact that I would need to fit this into my busy full-time kollel and family schedule. I was motivated, though, because I’m passionate about the subject, and I knew my wife would love the idea.

“Of course!” I said.

It was the only answer I could think of.

I had no way of knowing the extent of what delivering on those two words would entail. A lot more has been preserved about the period of the Rishonim because we’re closer to it. Also, we glean a ton of biographic and historical information from the responsa the Rishonim wrote, whereas we know about the lives of the Tannaim and Amoraim only from scattered details throughout Gemara and Midrash because they did not write responsa. Simply put, the Rishonim’s lives and the settings in which they existed are heavily documented: the Muslim and Christian cultures in which they lived, the difficult decrees and social and religious upheaval they faced (for example, the Crusades, the Black Death, the Almohad invasion, the reconquest of Spain, and the Spanish Expulsion).

Research for this project, I quickly learned, would prove to be far more tedious.

I began by scouring the literary material available on databases such as Otzar HaHochma and Hebrewbooks.org, so I could read through seforim, biographies, scholarly monographs (written accounts on a single subject), journal articles, and encyclopedia entries, but I quickly discovered that to take research to the next level, I needed access to more, much more. I needed access to a prestigious Jewish history library.

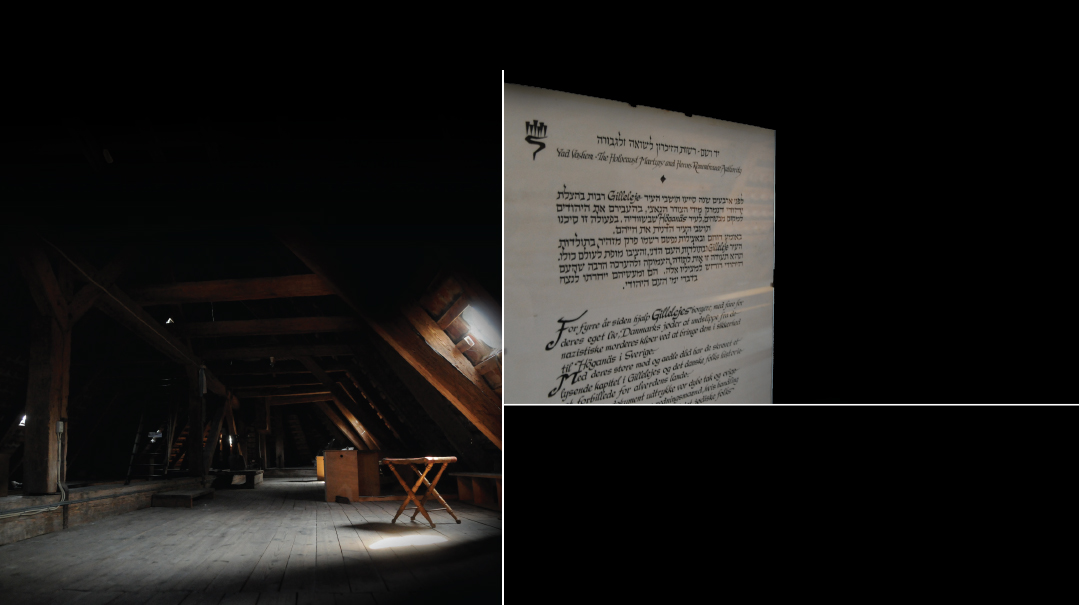

Here lies an incredible stroke of Hashgachah pratis. Our new home of Cincinnati, now a vibrant makom Torah, has a more notorious history as the founding base of the Reform movement. Because of its prominence in the Reform world, the city is home to the original Hebrew Union College, a rabbinical seminary founded by Isaac Mayer Wise in 1875. Included in the campus is the Klau Library, with its collection of staggering 530,000 printed books, 2,500 manuscript codices, and thousands of manuscript pages. Klau Library also features a rare book room containing 14,000 ancient and precious works; people travel from all over to avail themselves of these resources.

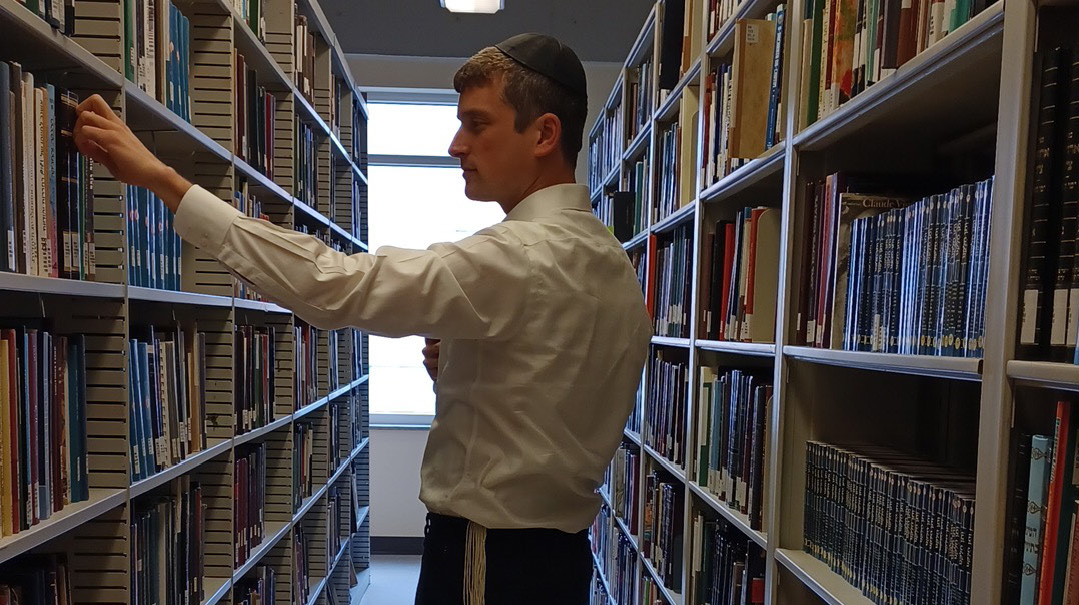

I’ll never forget the first time I entered the Klau Library with my laptop and a list of books I was looking for. It’s spacious and well-lit, and between the two-story high ceiling and the balcony overlooking the lobby, you can’t help but be impressed.

“Up there,” said the librarian when I asked where the books are shelved, pointing to a stairwell that led to the second floor.

I climbed the steps and made my way down the hallway to what they call the open stacks room, the main part of the library where anyone can go and take out a book (as opposed to other rooms that aren’t accessible to the general public). It was large and rather dark (I’d learn that you need to press the light switch for the aisle you want) with dozens of aisles of gray iron shelves packed with thousands of books. I slowly walked down the first row, searching for something ancient, something that would contain precious information about our heritage and our Rishonim. Some of these books were new, but some — I cracked open repaired bindings and peered at the publication dates — were more than 100 years old. I could feel centuries of Jewish history coming together before my eyes.

I rotated slowly, overwhelmed by it all. (And this was just one floor; the library has two more above it, in addition to the famed rare books and manuscript room in the basement, where they’re on a separate system for climate control and security.) After half an hour of scanning book spines and pulling interesting finds off the shelves, I went to find a librarian.

“I’m looking for biographical works on the Rambam, can you show me the way?” I asked, after which I got a crash course in library setup and protocol.

I learned that accessing material sometimes meant pulling books from the “closed” stacks (the part of the library which you can’t go into by yourself because the books are older, more delicate, rarer, or more valuable). I got advice about how to navigate the database of journal articles. Mrs. Avigaille Katz, who happens to be a neighbor, works as a librarian at Klau, and she taught me how to use the call number system to locate books. She also helped with scanning and translating books in other languages (a lot of the material on the Rishonim was written in German by Jewish German scholars).

Once I understood how to find the material I needed, my next challenge was to narrow it down to what was reliable and helpful to my research. It is not an exaggeration (in fact, it is likely an underestimate) to say that Klau Library has 50 books on any well-known Rishon. The sheer amount of material on my subject of interest meant there was so much to work with — but it was incredibly overwhelming. Take the Rambam: there are hundreds of published works — literally, between biographies and books on his approach to halachah, philosophy, medicine, and more — I had no idea where to start.

The solution came by way of a respected talmid chacham who is one of today’s premier Jewish historians, Rabbi Dr. Shnayer Leiman, a professor in the department of Judaic Studies at Brooklyn College and a visiting professor at Yeshiva University, both in New York. I had corresponded with Rabbi Dr. Leiman on several occasions for my first book and about other things I was reading about over the years, and he became an indispensable guide, directing me to which books provide pertinent and reliable material so I could focus my Rishonim research on a select few thorough and accurate resources.

The research took about two years. I vividly remember sitting at the doorway of my kids’ bedroom doing bedtime while plowing through page upon page of Israeli historian Avraham Grossman’s books on the Rishonim of France and Germany. My friends at kollel regularly threw questions at me about who certain Tannaim, Amoraim, Rishonim, and Acharonim were, and my chavrusas would oh-so-patiently listen when I shared my latest fascinating anecdote about who a certain Rishon or Acharon was, things like, “The Ra’ah [Rabi Aharon HaLevi, the author of Bedek Habayis] was actually living with the Rashba in Barcelona, and you know what, they may have even been chavrusas in the Ramban’s yeshivah in Gerona!” or “This Rabi Meir mentioned in Tosafos is Rabbeinu Tam’s father — he’s Rashi’s son-in-law!”

Even though it took over my life, my kids were pretty clueless about what book writing actually means. When my shipment of 64 copies of the newly printed Rishonim book arrived at our door, my five-year-old peered into the box and said, “Abba, you wrote all of those books?!”

There is a well-known sugya in Berachos (35b) in which Rabi Yishmael shares his view that learning Torah should be your main goal in life, while you should also set aside some time to make a livelihood and support your family. As I learned Rashi’s commentary on this sugya, where he explains the necessity of earning a livelihood, I thought about Rashi himself, who devoted his entire life to teaching Torah and writing his monumental commentary — and also managed to support his family. There’s a big debate about whether Rashi was a winemaker, the occupation of several French Rishonim. No one knows, but he balanced the obligation to support his family while being Rashi, the teacher of Klal Yisrael.

It’s impossible for a ben Torah to tally how much Rashi he learns over the course of his life. But having studied who Rashi was a rosh yeshivah, posek, communal leader, writer of massive commentaries on all of Tanach and almost all of Shas, and what his environment was like — 11th century France; the first Crusade was toward the end of his life in 1096 — studying his words becomes more an emotional experience than an academic endeavor. Suddenly, you aren’t learning, you’re bonding with the illustrious neshamah of a gadol hador from 1,000 years ago. I never met Rashi, but having delved into his life so thoroughly, I feel — really I wish — I had.

This same thought struck me when I studied one of Rambam’s letters to Sephardic Jewry of the 12th century, as recorded in Igros HaRambam. He wrote letters to everyone, but the most memorable for me is his letter in 1172 to the Yemenite Jews who were oppressed by the local ruler and confused by a false messiah who had just proclaimed the imminent arrival of Moshiach.

You write that the rebel leader in Yemen decreed compulsory apostasy for the Jews by forcing the Jewish inhabitants of all the places he had subdued to desert the Jewish religion just as the Berbers had compelled them to do in Maghreb, the Rambam writes. Verily, this news has broken our backs and has astounded and dumbfounded the whole of our community. And rightly so. For these are evil tidings, “and whosoever heareth of them, both his ears tingle” (Samuel I 3:11). Indeed, our hearts are weakened, our minds are confused, and the powers of the body wasted because of the dire misfortunes which brought religious persecutions upon us from the two ends of the world, the East and the West (translation from Sefaria).

Of course, I’ve learned plenty of Rambam over the years. I’ve asked questions, supplied answers, and engaged in heated debate over his true intentions about the kinyan of kiddushei kesef and his description of mitzvas ner Chanukah mitzvah chavivah hi ad me’od, but my study, albeit a treasured mitzvah, was intellectual in nature; there was no sense of connection to the Rambam, no appreciation for who he was and what lies in his sacred words.

Once I studied the Rambam’s letters, however, the depth of his blazing ahavas Yisrael was clear. He cared so deeply about the welfare of his people, you can see how he carried their burden on his shoulders: Verily, this news has broken our backs and has astounded and dumbfounded the whole of our community.

In another letter, the Rambam sincerely requests that people from all over the civilized world — Spain, Provence (southeastern France), Iraq, Syria, Yemen, wherever his Mishneh Torah reached — write to him with questions on his sefer. How can you not be moved by the humility of a talmid chacham, the leader of his day, who knew more than anyone, yet wished to hear from everyone?

One thing I’ve discovered, interestingly, is that a connection to Torah is critical to the study of history. In order to properly appreciate who the Rishonim were from a historical perspective, you must first understand what they meant spiritually. In order to write a biographic sketch of the Rambam or Ramban, one needs the proper context, an understanding of their greatness in all realms of Torah: their yeshivos, talmidim, and impact on Klal Yisrael as a whole, so you can understand what they did and why. For example, to understand Rabbeinu Tam’s harsh critique of those who made “corrections” in the Gemara, you need to understand what he stood for in terms of writing Tosafos and in unifying all of Shas into one halachic work. Every letter of Shas was so critical to him, Rabbeinu Tam couldn’t watch people play with the text and not reproach them.

In this regard, I owe a great debt to gratitude to the rosh yeshivah of Yeshiva of Greater Washington, Rav Aaron Lopiansky shlita. Rabbi Lopiansky’s shiurim extend deep into Jewish history, and because of them, I was able to approach this project with a sense of spiritual mission and the knowledge that the study of Jewish history plays a valuable role in increasing kevod Shamayim.

About 18 months ago, I sent Rabbi Lopiansky my complete manuscript for review. He replied with quite a few points, advising that I should more thoroughly research certain topics like the Ran’s sefer Torah, Rav Avraham Abulafia, and the story of the assassination of Rabbi Yehosef Hanagid, instead of relying on just one or two less well researched sources.

The story about Tes Teves being the day when they killed Rabbi Yehoseph Hanagid is indeed mentioned, Rabbi Lopiansky commented in an email. But it does sound very strange. In history there are so many more monumental events and difficulties that happened, why would this be the event mentioned in Megillas Taanis?

He also suggested I put together a bibliography, stressing that everything I cite must be sourced, otherwise the work is not valuable (there are lots of historical “likutim” out there, i.e., Shalsheles Hakabbalah, who compiled just about everything he heard without verifying if it was true; we need to be cautious with his material). To source what we know and demonstrate how we know it to be historical fact is a whole new level, Rabbi Lopiansky advised.

Six months later, after I implemented many changes based on Rabbi Lopiansky’s direction, he was also gracious enough to write a haskamah, and I finally submitted the manuscript that summer. Judaica Press released The Rishonim three months ago, right after Purim.

I look back at these two books and think of the dozens of revisions I put into them. Enhancing, clarifying, and correcting the content, reorganizing to make the sequence of events or patterns clearer, removing tangential and distracting material, citing all sources meticulously, and more.

You know what I’ve learned? Revising is a plus, not a minus. No one — not even Rashi — gets it 100 percent right the first time. We’re human and mistakes are inevitable, so it is critical to review and redo.

As I discovered in my research, many Rishonim wrote several mahaduros (editions) of their seforim — they actually changed their minds. Rashi revised his commentary on Shas not once, not twice, but three times. There are countless contradictions between the Rambam’s peirush on the Mishnah and in his Mishneh Torah, but several Acharonim comment that these aren’t contradictions — rather, after years of learning, chazering, and delving deeper into the sugya, the Rambam changed his mind.

I look at the book on my shelf now, in the days leading up to Shavuos, and I find myself reflecting on Matan Torah. All of Klal Yisrael was present at Har Sinai: Tannaim, Amoraim, Rishonim, and Acharonim alike. And us — we were there, too.

Like Torah, Klal Yisrael itself transcends the confines of nature, a timeless fusion of past, present, and future.

Which is why, following the release of The Rishonim, looking forward means looking back.

What I’m hearing now is, “So what’s next? A book on the Acharonim?”

Perhaps.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 1015)

Oops! We could not locate your form.