Living in the Dark

| April 9, 2024Why would anyone keep their home so gloomy when free sunlight was readily available?

MY grandparents lived in the dark. Literally. Born in Germany, they made a short stop in Italy as they escaped Hitler’s clutches, and after ten years in La Paz, Bolivia, they turned finally to the United States, settling, like so many Jewish immigrants, in New York. In those days of incandescent bulbs, lighting a room came at considerable cost. Leaving a room without shutting the lights was simply verboten in Oma and Opa’s apartment.

But even with the lights on, the rooms seemed dim, with no discernable difference between day and night. I attributed this darkness to the situation of their living quarters. Theirs was a ground-floor apartment, generally a highly coveted commodity. But their building was built on a hill, so while the windows of some rooms were at eye level, in other rooms the windows were too high for anyone to reach. No wonder it was permanently dark.

After my grandparents passed away, my father took over their apartment, redecorated, and moved in. He threw open shades all around. And lo! Sunlight suffused every room. I was aghast. I couldn’t understand it; my grandparents had chosen to live in the dark. I’d never seen a window shade open when they were there. I didn’t even know the windows were there; I’d assumed we were too far underground.

For years, this perplexed me. Why would anyone keep their home so gloomy when free sunlight was readily available? I could not conceive an answer to the mystery.

Then one day, it occurred to me. Oma and Opa had escaped Europe with the Nazis so close behind them, they could practically feel their breath. In Bolivia, they became somewhat well-to-do. But one day, Oma took her three young children to the park where they began to scamper over some statues. Two men sitting on a bench looked on in disgust. Then, in German, one said to the other, “Those Jews ruined Germany. Now they’re going to destroy South America.”

Seemingly, they didn’t know Oma spoke German. Or perhaps they didn’t care. Either way, Oma quickly rounded up her children and took them home. “We’re leaving,” she told her husband simply. Heading for the US, Washington Heights was a natural choice, with its thriving Yekkish community. It was there Oma and Opa would spend the rest of their lives.

Looking back on all this, I wondered. Maybe Oma and Opa were in a permanent state of hiding. Being Jewish, they had learned, was not safe. Better for no one to see. For no one to know who lived behind those shuttered windows. After all, they told me over and over, “It could happen here, too. We never thought such a thing could happen in Germany.”

Somewhat smugly, I pitied my grandparents posthumously. Poor Oma and Opa, stuck in the past. They couldn’t understand that things are different here. This kind of thing doesn’t happen — can’t happen — in America. Why, we have a constitution and laws that guarantee equal rights! We have a government chosen by the people — including us. What a shame that my poor immigrant grandparents let their past color their entire existence, I thought.

But, as the tentacles of wokeism spread around the country, I watched anti-Semitism stir from its slumber. Frightening events occurred, hitting closer and closer to home. But it was okay. There will always be some people who hate Jews, I reasoned. Most Americans understand that we’re human just like they are. Most know we’re good people just trying to do our best, pursuing our flavor of the American dream — to live in peace and prosperity and practice religion free from persecution. The volcano of hate, the stories of inquisitions and pogroms and concentration camps, I thought, were extinct.

I couldn’t deny my stirrings of uneasiness as the Western world teetered ever more precariously to the left. But as much as things changed, as much as I heard my grandparents saying, “It could happen here, too.” Deep down, I knew things were different. History was behind us. The present was rosy and bright.

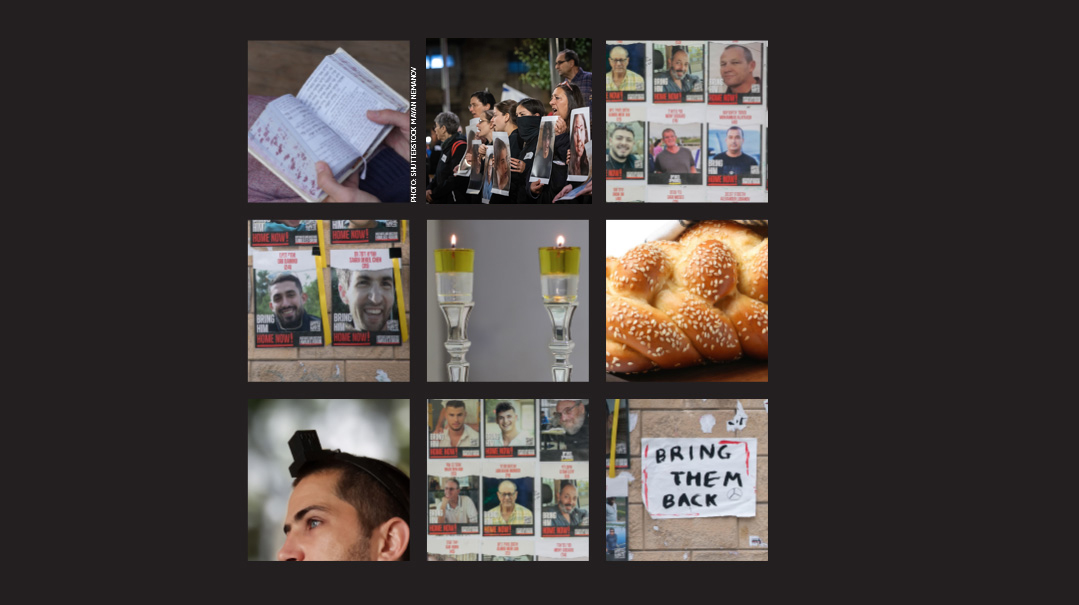

Then, Simchas Torah, 5784. The most joyous day of the year turned to the most unbearably tragic, shredding our collective hearts almost beyond repair. We were all shocked when, before the dead were yet buried, the sleeping dragon awoke; the volcano erupted in all its historic fury. Anti-Israel (read: Jew) protests arose in every corner of the globe, attended not by dozens, nor hundreds, but thousands of screaming, rabid, depraved beasts, crying, “Gas the Jews!” and “Hitler was right!” We looked on stunned as the presidents of three of the US’s most respected houses of learning proved unable and unwilling to condemn calls for Jewish genocide.

But after the initial shock, I felt embarrassed by our collective foolishness. How could we have been lulled into complacency yet again? The cycle of Jewish history has repeated itself so many times; what made us think the wheel had stopped turning? What made us think that our generation’s ascent to prominence and wealth would not give rise to a fresh wave of this stale bigotry? That we had conquered the beast and reached the end of times?

My perspective changed forever on October 7. I know now how right my grandparents were. My enlightened generation notwithstanding, it turns out it was I who was living in the dark.

(Originally featured in Family First, Issue 889)

Oops! We could not locate your form.