Lessons for the Good Life

“If you don’t know what you’d be willing to die for, you don’t know why you are living either”

I found Clayton Christensen’s graduation address to the 2010 class of Harvard Business School (HBS) amid one of the many piles of papers that cover my floor. I have no idea how it got there.

Christensen was an obvious choice for graduation speaker: a professor at the business school; author of The Innovator’s Dilemma, considered one of the most influential business books of all time; and a former successful CEO.

But none of those was the primary reason the class invited him. They also knew he was one of the most religious faculty members — a devout Mormon — who had spent much time considering the question: What constitutes a good life?

The class members had applied to business school during a roaring economy, with prospects of riches before them, only to have the bubble burst in 2008, shortly after their entry. They asked Christensen to address the application of his business principles to success in life, rather than to success in business. His graduation speech, titled “How to Measure Your Life,” was the result, and it subsequently became a full-length book.

Christensen relates that during his two years as a Rhodes scholar at Oxford University, while trying to cram a three-year econometrics program into two, he nevertheless undertook to spend an hour each evening reading, thinking, and praying to understand why G-d had put him into the world. He stuck to his commitment, and reported that he thought about his early efforts at identifying his purpose every day for the rest of his life (but used his econometric tools no more than a couple of times per month).

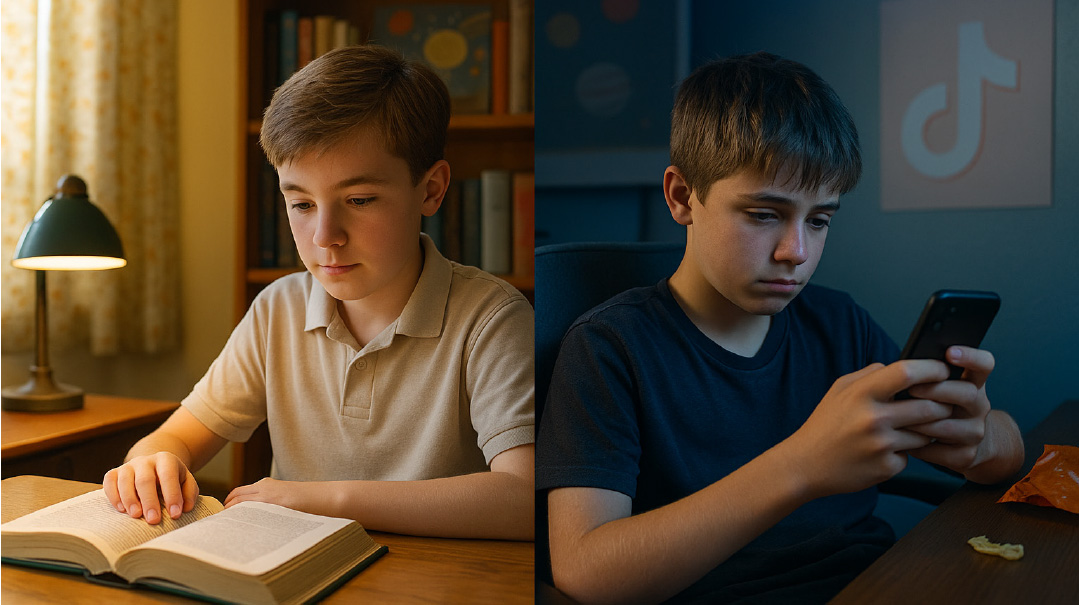

One of the things he came to realize was that most people, but especially high achievers, tend to devote most of their mental energy to that which pays the most immediate rewards, as opposed that which will provide the most lasting lifetime satisfaction —i.e., loving familial relationships. Over the course of his five-year Harvard Business School reunions, he noticed that an ever larger percentage of his class were divorced and estranged from their children. None of them had planned to be divorced or estranged parents. But neither had they spent much time thinking about how to nurture a family.

Even in the business context, he cited evidence that money is not the ultimate motivator it is assumed to be. Rather, opportunities to learn, grow in responsibilities, contribute to others, and be recognized for achievements are more important. At the time he delivered his graduation address, Christensen had already been diagnosed with the leukemia that would claim his life a decade later. Though his ideas had resulted in companies earning vast profits, he found that what gave him far greater satisfaction was thinking about all those whose self-esteem he had built as a manager.

Perhaps the most interesting part of the address was his discussion of his third key for a good life: “How to stay out of jail.” Whenever I read of someone caught in a massive scandal, I always have the same question: What were they thinking? Did they ever think of the humiliation and suffering of their loved ones if caught?

At least two members of Christensen’s Rhodes scholarship class of 32 had already served time in jail, and an HBS classmate was the CEO of a company involved in one of the most spectacular business frauds in history.

Those who end up in jail, he opined, usually started with “just this once.” They tend to rate the “marginal cost” way too low against the gain of breaking a general rule of behavior.

While at Oxford, Christensen was one of the mainstays of the Oxford basketball team. The team was undefeated, and was slated to play for the British university championship. The only catch was the championship game was on Sunday, and at 16, Christensen had taken a vow that he would not play basketball on Sunday.

He knew he was letting down his teammates, whom he described as the best group of friends he ever had, and indeed they were incredulous at his decision not to put aside his vow “just this once.” But as painful as that decision was, he came to view it as one of the most important in his life: “If I had crossed the line once, I would have done it over and over.” As Chazal say, the third time a person repeats an aveirah, it is already in his eyes a mitzvah. That is why it is much easier to hold your principles 100 percent of the time than 98 percent.

The concluding insight of Christensen’s address was that humility is a crucial component of the most successful people. And that humility, paradoxically, is based on high self-esteem. Because they value themselves, they have no need to look down on others. Accordingly, they respect others too much to lie or cheat them.

Admittedly, most HBS graduates will spend their lives around people less intellectually gifted than themselves. But that should never lead one to think that he has nothing to learn from them, Christensen counseled. “Who is wise? One who learns from every person.”

I SIMILARLY LEARNED of Venezuelan opposition leader Leopoldo Lopez, of whom I never heard, by happenstance. He is blessed with brains, good looks, and a distinguished lineage — he is a direct descendant of Simon Bolivar, the leader of South American independence from Spain. Lopez graduated Harvard’s Kennedy School of Government, and had lucrative offers from McKinsey and J.P. Morgan, but decided to return to Venezuela, where he eventually founded a democracy movement to fight the dictatorship of Hugo Chavez. After leading mass protests in 2014, he had the choice to flee the country or be arrested. He chose the latter, spending almost half of his three and a half years in prison in solitary confinement.

Asked whether the three years in prison and separation from his wife and children were worth it, he answered, “Yes, I think it was worth it. Though it was a great hardship for me, and a greater hardship for my family, my children now have something that can be cherished: a sense of purpose, the willingness to fight for any idea. I can’t think of a better inheritance.... In the end, happiness is about having a sense of purpose, and my children have now been part of an experience that will make them happier and better people.”

Rav Noach Weinberg used to tell his students, “If you don’t know what you’d be willing to die for, you don’t know why you are living either.” Leopoldo Lopez fully illustrates that principle and passed it to his children.

TWO WEEKS AGO, my Har Nof neighbor Ronald Markowitz passed away in his late eighties. Thirty-eight years ago, at the age of 49, he was diagnosed with pancreatic cancer, and was told after surgery that he had a 5 percent chance of living out the year. He lived to be at a great-grandson’s bar mitzvah.

Pancreatic cancer is one of the most dread diagnoses of all, for it is almost always caught too late to be treated effectively. But for Ronald, it was life-changing for the good. From the moment he was diagnosed, every single day became a gift to be lived with enthusiasm and gratitude to Hashem.

If Hashem had given him so many more years than he was entitled to expect, Ronald was determined to live them to the maximum. Into his seventies, he was still walking to the Kosel from Har Nof with his son and grandson many Shabbosos, an hour and a half each way.

In his final hospital stay, after being felled by a massive heart attack, the monitors in his room were changed six times, as the doctors and nurses could not believe that someone with his low vital signs could be as responsive as he was. When he was asked whether he wanted to have tefillin put on, his feet started dancing frantically. The same when a son arrived from the States after multiple delays.

Even as his and his wife Miriam’s physical strength decreased, they occupied themselves in all kinds of giving. The walls of their building, including the usually forlorn hall outside the storage rooms, were festooned with large, colorful jigsaw puzzles that they lacquered and framed. For 20 years, they maintained a gemach of laptops, in memory of a deceased son, for those confined in hospitals.

A nephew — whom Ron largely raised after the passing of the boy’s own father in his forties — wrote from the plane on his way to make a shivah call to Ron’s sister and his aunt that he was relieved no one was sitting next to him, so copiously did the tears flow as he thought of his beloved uncle.

Ron fully repaid the gift of life from Hashem by living every moment to the maximum.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 891. Yonoson Rosenblum may be contacted directly at rosenblum@mishpacha.com)

Oops! We could not locate your form.