Lead like a Lion

The rabbi has lions in his study.

Sure, he has rabbi stuff — seforim and letters, pictures and shul artifacts — as well, but the ornamental beasts of brass, stone, and glass crouch all around.

Part metaphor, part history, part mission statement; they represent Rav Avrohom Yitzchak Levene’s legacy. The lion hints at the first names of two of the most seminal figures in his life, his paternal grandfather, Rav Aryeh Levine of Yerushalayim and his maternal grandfather, Rav Yehuda Leib Levene of London.

It serves as a symbol of the leadership model that served him through more than a half-century in synagogue rabbanus.

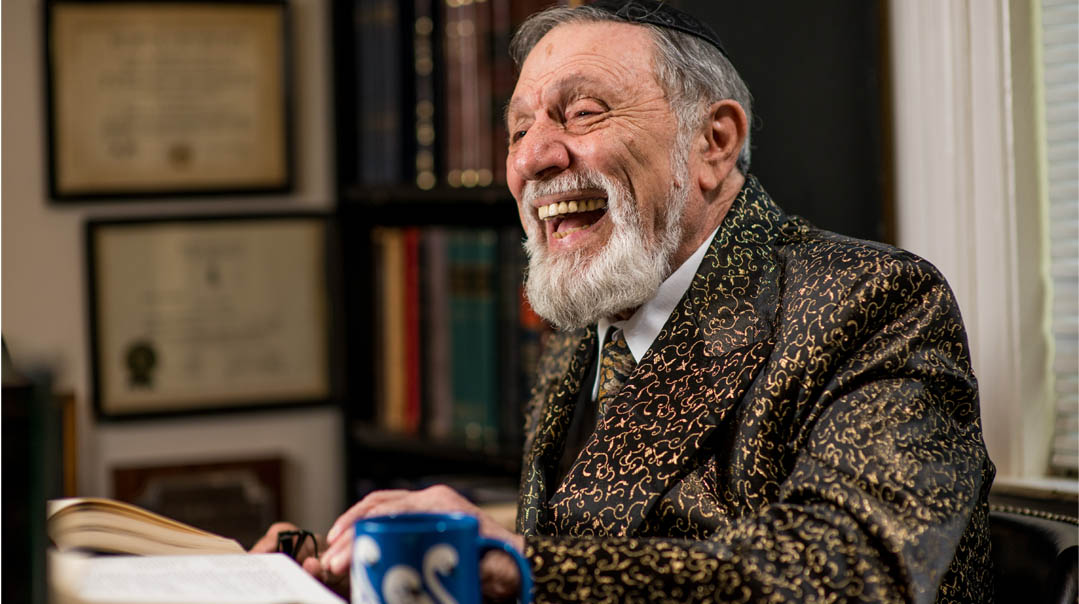

The impeccably dressed rabbi — elegant black and gold smoking jacket perfectly matched with his necktie — is in darshan mode. Many of the figures who play roles in the rich life of Rabbi Levene occupy places of honor in the communal memory-bank. Happily, his raconteurial abilities match the color of his subjects; his recollections do them justice.

I WILL BE THERE

There are people who tell stories. Like an actor dropped on stage in mid-scene, Rabbi Avrohom Yitzchak Levene was born into a story.

Where to begin? Like all good tales, it starts in Jerusalem, where a young couple awaited the birth of their eldest child. It was a time of unrest in the Holy City, and the shock caused by an explosion near the small apartment had sent the expectant woman into a mini-coma.

Her father-in-law, known as “the” tzaddik in a city filled with saints, and her husband, one of the most accomplished young scholars in a world where there was no currency other than scholarship, poured out their hearts in prayer.

One night, Rav Chaim Yaakov Levine sat learning, his unconscious wife in the next room. He dozed off and dreamed that his father’s recently departed rebbi, Rav Avraham Yitzchak HaKohein Kook, appeared to him.

“Why is the Rav here?” Rav Chaim Yaakov asked.

“I came to be mevaker choleh, to visit your wife. She will have a refuah sheleimah.”

“And what will be with the child?” asked Rav Chaim Yaakov.

“The child will be fine, and I will be at his bris,” the otherworldly visitor assured him.

A healthy boy was born and named in honor of Rav Kook, little Avrohom Yitzchak Levene, one of the first children to carry the illustrious name.

Now, close to eight decades later, that child — recently retired from one of the more prestigious pulpits in the United States — welcomes me to his attractive Philadelphia home.

FIND ANOTHER JOB

There is so much to look at here, so much to see. The house is charming, bursting with personality and flair, but the people are even better. What gets you is the smile: it’s the Levene brand and they’ve been doing it for generations.

But there is something in Rav Avrohom Yitzchak’s appearance that sets him apart from others in his family; a certain firmness, the way he squares his shoulders, the tight grasp of his handshake that tells of a certain resolve.

He laughs at the observation. “I’m a shul rav; if you’re not prepared to fight for what you believe, find another job.”

And with that, he tells me about the other part of his birthright, the lesson received from the other “leib,” his maternal grandfather.

NEVER BE AFRAID

“My maternal grandfather, Rav Yehuda Leib Levene, was a talmid of the Chofetz Chaim and lived in London. My zeide Reb Aryeh was close with him for years before they would become mechutanim, he’d even stayed at his home when visiting London.

“My mother, who had graduated business school in London with honors, had one ambition in life; to marry a talmid chacham. Knowing that the chances [for a shidduch] were better in Eretz Yisrael, she saved up her money and traveled there. Of course, my zeide Reb Aryeh, who felt like an uncle toward her, insisted that she be his guest. Different as she was in background from my father, she was similar to him in her burning ahavas Torah and my zeide wanted her for his son, prize talmid of Rav Boruch Ber Leibowitz and one of the most sought-after bochurim in Yerushalayim.”

Shulamis Levene’s dream of becoming an eishes chayil was fulfilled. “Chayi’’l is an acronym of my father’s name, Chaim Yaakov Levene,” her son jokes. “But on a serious level, it was a perfect match. My father never stopped learning and she never stopped being proud.”

(In time, Reb Chaim Yaakov and his children would adopt the spelling of the London Levene’s for their own last name, even as the more standard “Levine” is generally used for Rav Aryeh and others in the family.)

“I vividly remember visiting my grandparents in London, even though I couldn’t have been more than a few years old.”

A painting hung on the wall of the Levine home, a young girl sitting on top of a haystack. “Something about the picture made me so sad. My uncle saw how upset I was and he removed the picture from the wall. My zeide noticed and asked why he’d taken it down. When my uncle explained that it frightened me, my zeide directed him to hang it right back up. Then he carried me over to the picture and spoke gently, softly.”

“You should know,” Rav Yehuda Leib whispered in his grandson’s ear, “that a Jew should fear nothing except the Ribbono shel Olam; there is nothing else to be scared of. A Yiddishe kind has to know that.”

“I was a rav for close to 60 years,” Rabbi Levene says, leaning back in his chair, “and I never forgot that advice. I repeated this story in my mind countless times over the years. He used a Russian expression, Nyeh bayus yah, which means to never be afraid. I was never scared of opposition, of threats, of losing my job, because my zeide told me not to be. Only of the Ribbono shel Olam.”

Against the backdrop of these two stories — piety and resolve — he weaves a tale of one of the most successful rabbinic careers of the last half-century.

WHAT IT MEANS

Young Avrohom Yitzchak was raised in various locales. His parents were visiting London when turbulence in Eretz Yisrael closed its borders. Rav Meir Bar-Ilan suggested that America was in desperate need of a talmid chacham of Rav Chaim Yaakov’s stature.

“My father was offered to say shiur at Yeshiva University and when he tried it out, an elderly gentleman came in along with the bochurim. He explained that he was the maggid shiur who’d just retired and he just wanted to ensure that his replacement was a talmid chacham. My father perceived that the fellow hadn’t gone of his own volition, so my father turned down the job.”

This fusion of gaonus and exalted middos wasn’t unique to Rav Chaim Yaakov. “My zeide had this close-knit chaburah of friends from when he’d been in yeshivah in Halusk [Poland], so when we arrived in America, we went to visit them; Rav Yitzchak Segal of the Agudas Harabbanim and Rav Yosef Eliyahu Henkin.

“We went to Rav Henkin’s home directly from the port and I was starving. He served honey cake and when I asked for a piece, he looked at my father. ‘You’re planning to send him to school here, in America, but he speaks English with a British accent. Teach him to speak like an American so he won’t be embarrassed here.’ ”

The comment made an impression on the young boy. “I was only four years old, but I understood his message. I think he was making a point about the importance of communication, about what it means to be a rav.”

A DREAM

The Levene’s made several stops in North America. Rav Chaim Yaakov served as rosh yeshivah in Seattle, Washington, before finally establishing himself as a rav in Jersey City, where he remained for years, making a major impact.

When he turned 12 years old, Avrohom Yitzchak became the youngest talmid at the relatively new Telshe Yeshivah in Cleveland, Ohio, before it established itself in Wickliffe.

“But I dreamed of learning by my zeide Rav Aryeh and eventually, my parents agreed.”

The teenager set off, spending the Yamim Noraim in London with one zeide before continuing on to Eretz Yisrael, to the other one. Arriving on holy soil was like being dropped into the middle of a storybook, a fantasyland of saints and scholars, the pious and poor.

“Those were the most glorious times… I learned by my uncle, Reb Leizer Plachinsky. The chevreh included many cousins, At night, I hung around with the Zeide. I would join the shiur he gave in a little shul in the Knesses neighborhood.”

On Shabbos, the American grandson would accompany his zeide on his visits. “He would go visit his mechutenes, whom he called ‘Hummler Rebbetzin’ — the mother of Rav Elyashiv!”

And of course, the uncle himself. “In later years, whenever I would come to Eretz Yisrael and try to get into Rav Elyashiv, my Doda Chaya would push me to the head of the line. ‘My husband likes talking to you,’ she would say.”

In later years, when Rav Elyashiv carried the responsibility of ruling for a nation and his nephew was leading a congregation in Philadelphia, Rav Elyashiv — interested in the perspective of a shul rabbi about certain issues — would ask what his nephew thought about various topics.

“There was a mess here in Philadelphia when two Jewish kids were playing around, there was a mock wedding, and the teenage boy was mekadesh a girl as a joke. It was a very serious sh’eilah as to how to proceed. On my next trip, Rav Elyashiv wanted to hear how we handled it: He was pleased with my psak.”

Another family member with whom he got acquainted was the chassan of his cousin. “My cousin Batsheva Elyashiv got engaged to a brilliant bochur, a son of the Steipler Gaon of Bnei Brak. I remember the shtickel Torah he said when he came to visit the Zeide, about a Rambam that appears to miss a gemara.”

Many years later, the Philadelphia cousin was visiting Rav Chaim Kanievsky and he reminded the gadol about the insight. “He was delighted to be reminded about that shtickel Torah.”

Which Rambam, I ask, curious. My host studies me for a long moment. “Aha, you want it to come so easy? You heard what I said; it’s a Rambam that appears to overlook a gemara, that should be enough information to get you started… go figure it out,” he challenges.

IF HE WANTS

At the festive wedding, Reb Aryeh brought his American grandson over to receive a brachah from the chassan’s uncle, the Chazon Ish.

“I saw him. I saw the Brisker Rav. Listen to this story.”

If someone would tell me that they are giving out $20 bills outside, I don’t think I would be able to get up. I’m in complete surrender to this man and his stories.

“My uncle, Reb Leizer Plachinsky, was a talmid of the Brisker Rav, so I longed to visit him. Finally, the opportunity presented itself and I visited the apartment.”

The American bochur was offered a seat and the Brisker Rav studied him. There was total silence in the room.

“The Rav made a brachah on his tea and I said ‘Amen,’ waiting for him to talk. Finally, it became clear that he wasn’t going to say anything more than ‘Nu.’ ”

The bochur shared a shtickel Torah he’d developed. The Rav listened, and then said, “Ess toig nisht, it’s not correct.”

“That was it. The conversation was closed. I stood up and left.”

A full year later, when Avrohom Yitzchak was preparing to return home, Reb Aryeh wanted to take the bochur to the Brisker Rav for a farewell brachah.

The Rav welcomed Rav Aryeh and invited him to sit down. Reb Aryeh introduced his grandson, “This is my einekel from America, he’s going home and wants a brachah.”

The Rav looked up. “Fuhr gezunt, kum gezunt,” he said, safe travels.

“He also wants a brachah for hatzlachah in learning,” Rav Aryeh prodded.

“Oib ehr vet vellen, if he’ll want,” the Rav replied, “then he’ll be successful.”

The Rav fixed his stare on Avrohom Yitzchak. “Farvoss toigt ess nisht?” he demanded. What was wrong with the shtickel Torah of the previous year.

The bochur told the Rav what he imagined the error was and the Ravv’s face brightened.

He looked at the bochur with satisfaction and aid, “Nu, efsher vet ehr takeh vellen, maybe he’ll actually want.”

Rabbi Levene attributes much of the blessing in his life to his daily encounters with Rav Isser Zalman Meltzer.

“There was a near-constant state of war during that period, so there was no such thing as fresh milk in Yerushalayim, only powered milk. Though Rav Isser Zalman allowed its use for others, he himself wouldn’t use the substance.”

But the elderly rosh yeshivah needed milk for his health, so Rav Aryeh Levine located an old Yemenite gentleman who owned a goat, and arranged to purchase goat milk for Rav Isser Zalman.

“Each morning, I brought him a jug of milk, and the shower of his brachos would accompany me down the long staircase.”

Though his rapture at being in Holy City kept growing, there was pressure from home to return.

“In addition to the constant danger and shortages, I had health issues as well and my parents wanted me back, to learn closer to home.”

The trail of great stories followed him onto the airplane home as well. “Before I left, my zeide handed me a well-wrapped package, a gift for my father, and he told me to watch it carefully. When we got to the airport, my zeide greeted this distinguished looking rebbetzin and introduced me, his einekel. It was Rebbetzin Hutner, wife of the rosh yeshivah of Chaim Berlin, and she told my grandfather, ‘Daageh nisht Reb Aryeh, don’t worry, I’ll keep an eye on your grandson on the flight home.’ ”

At one point on the long flight, the teenage traveler needed the washroom. “I wasn’t sure what to do with the package, the Zeide had told me not to let it out of my sight. The passenger next to me was drunk. I approached Rebbetzin Hutner and told her I have a sh’eilah. ‘The Zeide told me to watch this package, and he asked you to watch me; perhaps you can watch this for me?’ ”

She smiled and said, “I’m not a rosh yeshivah or rav, but I am sure it’s fine if I watch it.”

The package turned out to be a most precious gift, a one-volume Shishah Sidrei Mishnah which had belonged to the Netziv. “He’d given it to his son, Rav Chaim Berlin, who gave it to my zeide. My zeide reasoned that his son, my father, was ‘memulach mimenu,’ a bigger talmid chacham than he, and so it belonged to him.”

Rav Chaim Yaakov would give it to his oldest son, and the cherished gift sits on the bookshelf behind me, in a place of honor among rows of prized seforim.

IN A WARM CLIMATE

The bochur arrived home and, with an eye on semichah and a career in rabbanus, he joined Yeshivah Torah Vodaath.

“It was an opportunity to be close to my father, in Jersey City, and to learn by great men.”

Avrohom Yitzchok Levene, a Litvak through and through, was taken by the breadth and profundity of Rav Gedalia Schorr. “I had never really been exposed to sifrei chassidus, so it was exhilarating. My father knew all the chassidim and rebbes, but I didn’t. Until today, I love sifrei chassidus because of Rav Schorr.”

Rabbi Levene has several pairs of eyeglasses, and he wields them like a conductor waves a baton.

“Chinuch isn’t just what you teach, but how you teach.”

He tells me about his entrance to the world of practical halachah; the Chullin shiur given by the rosh yeshivah, Rav Yaakov Kamenetsky. “He came in the first day of the zeman and asked “Did anyone here ever read mysteries?”

The bochurim nodded.

“How come Sherlock Holmes was always able to crack the mystery and Watson, nebach, was always oblivious? It’s because Sherlock Holmes knew how to look for clues; he noticed things, not only what was there, but what wasn’t there.”

The bochurim were captivated. “Now, you have to realize that every word in Torah is a mystery. There are clues everywhere; a hashmata, an extra word, a change in lashon. That’s how we reach a conclusion.”

“That,” Rabbi Levene concludes, “is greatness. A litvish rosh yeshivah, a tzaddik, a gaon, who discovered a means of connecting with American bochurim and wasn’t afraid to use it.”

Avrohom Yitzchak had no doubt as to where his future lay; in the interests of being an effective rav, he earned psychology degrees from Yeshiva University and New York University and, more significantly, received his semichah.

“After earning semichah from Torah Vodaath, it meant a lot to me to be able to do shimush and receive semichah from my zeide’s friends, Rav Segal and the one who’d welcomed us to America 20 years earlier, Rav Henkin.”

Rav Avrohom Yitzchak Levene also earned the coveted stamp of rabbinic approval from the Zeide himself, Rav Aryeh Levine.

HIS FATHER’S FOOTSTEPS

The newly ordained rabbi followed his revered father’s career path, going off to teach at the yeshivah in Seattle for a year before returning home to join the staff of his father’s yeshivah, Yeshiva of Hudson County. After assuming the leadership of his first congregation, on Cottage Street in Jersey City, he finally paused to catch his breath and set up a home of his own.

He had the pedigree. He had the training. And now he had a wife. Rebbetzin Chana Levene, the daughter of Monsey’s well-known Cantor Jack and Belle Rosenbaum, was prepared for life as a rabbi’s wife.

There were no shortage of offers for the young rabbi. One of the oldest congregations in Philadelphia had a vacancy and, in 1967, Rabbi Levene was invited to come try out.

“But when I arrived, I saw that there was an organ in the shul and that the mechitzah was too small. They assured me that the organ was decorative, and that they were open to discussing the height of the mechitzah.”

The rabbi’s decisiveness is evident as he recalls the negotiations. “I said, ‘Great, you can call me back when the organ is gone and the mechitzah is fixed.’ ”

Being a straight talker, the rabbi also informed them of his intention to consider other positions. “I wouldn’t try out for two jobs at once, and there was an opening at the Lower Merion Synagogue, also in Philadelphia. They laughed and said, ‘You’re trying out there? You’ll come running back to us; someone with your yichus and skills isn’t taking that job.’ ”

A little cloud of wistfulness seems to settle on the rabbi’s study. His voice softens. “It was a little house. It had a real mechitzah. It felt like a shul. What can I say? It captured me from the moment I walked in. I accepted their offer.”

IT FELT LIKE A SHUL

The first Orthodox shul in Philadelphia’s Bala Cynwyd neighborhood had worked hard to establish itself. The shul didn’t have many members or much money. The newly established yeshivah of Philadelphia “loaned” them bochurim to help with a daily minyan but the congregation had weathered machlokes and was in the process of trying to rebuild.

Just days after the rabbi assumed the position, one of the shul old-timers looked at him. “The new rabbi, huh? Well, I guess I should say ‘Hamakom yinachem es’chem’ and console you for taking the job at this place.”

Rabbi Levene looked him in the eye. “Listen to me. If we are to remain friends, don’t dare talk negatively about my shul or my balabatim ever again.”

The cynical fellow stared at the rabbi, and then started to cry. “I’ve been a member here for decades and I’ve been waiting for years to hear someone talk that way. I’m behind you all the way.”

Philadelphia was, at the time, a stronghold of Conservative Jewry, but the newcomer was undaunted.

Rabbi Levene had been trained in both rabbanus and chinuch. “I never doubted that education, allowing and enabling people to learn and experience Torah, is the only way to build a vibrant kehillah and strong Orthodoxy.”

Alongside the shiurim in shul, he was invited to deliver shiurim in the yeshivah. “The yeshivah was more Lakewood-style, Rav Elya Svei and yblct’a Rav Shmuel Kamenetsky were talmidim of Rav Aharon Kotler, but in those years, the yeshivah attracted some locals as well, generally college students who also wanted to learn in-depth.”

The roshei yeshivah created a framework for these students, inviting Rabbi Levene to deliver the shiur. “One day, I open the door during the shiur and I see Rav Elya standing there. I was surprised and asked if everything was okay. He smiled and said, ‘Yes, I’m just listening to your shiur… I enjoyed the vort you said from the Maisheter Iluy, I haven’t heard it in many years.’ ”

IT’S MY PROBLEM

Rabbi Levene has been known to leave his seat on the eastern wall and circulate among the congregants, shaking hands and embracing visitors to the shul. The shul and neighborhood is a bastion of intellectual elite (the rabbi posits that it’s the shul with the highest percentage of college-educated members in America), yet his most effective tool remains his smile.

“As much as it’s about ideas, it comes down to how you relate to the people. You need both.”

It was Rabbi Levene’s smile that carried the shul through difficult times as well. “The space industry was heavily based around Philadelphia, and when it downsized in the early 1970s, many of our members were suddenly jobless. The president left. People were moving away and eventually, the treasurer informed me that there was no more money in the account to pay the utilities.”

But the rabbi didn’t let them shut the lights. “I paid the bills myself, not because I am wealthy but because I reasoned that as long as the shul exists, it’s my problem.”

He also believed in his own cause. “I knew that this was a shul formed by sincere people. They’d always worked hard to have a rav, there were several choshuv rabbanim before me, and they’d always respected their rav. I figured that the good days would come.”

By 1979, things were looking up. “We had 80 committed members, and we made plans to build.”

And of course, nothing happens without a story.

BUT WITH EMUNAH

Rabbi Levene used to deliver a weekly downtown lunchtime shiur. One day, he received a note from one of the participants, a businessman named Dr. David Wallach.

Dear Rabbi Levene,

I really enjoy your class, and wait a whole week for it. Please accept my gift as a show of thanks,

Your friend, David Wallach

Enclosed was a check for $1,000.

The rabbi wasted no time in penning a return letter.

Dear Dr. Wallach

You have given me more joy than you can imagine; we are bound through Torah! I hope you won’t be insulted, but Torah is the greatest gift, worth more than money. It is that bond that really connects our hearts. Keep coming to the shiur,

Rabbi Levene

And with that, the rabbi returned the check.

Dr. Wallach was amazed, telling the rabbi that no one had ever returned a gift to him. The relationship deepened over the years.

“So now it’s 1980,” the rabbi says, waving his glasses, “and we need a shul building, but we can’t get a mortgage.”

The bank president explained that he needed signatures from all 80 members of the shul. “Let’s be honest, I’ll never be able to foreclose on a synagogue, so unless you all make it personal, we can’t give the loan.”

The board members looked at Rabbi Levene, their despair evident. “We will never have a real shul building.”

The rabbi squared his shoulders. “Shuls aren’t built with money, but with emunah. Now we stop building like businessmen and start building like Jews always did.” He offered a challenge. “I’m willing to put my emunah where my mouth is. I guarantee you that the president will invite us back and give us the loan.”

The rabbi pauses in mid-story to reflect. “I had no choice,” he shrugs, “they were challenging emunah.”

A week later, a somewhat baffled board member told the rav that they’d been invited to a second meeting with the bank president.

“It turned out that our friend, Dr. Wallach, an investment banker, worked in the same building as the bank and he’d heard about the synagogue that needed a loan. Dr. Wallach didn’t tell us, but he informed the president that he would personally sign on the mortgage.”

The president was delighted to approve the loan, but the rabbi wasn’t fully convinced. “I thought we don’t do money,” he told Dr. Wallach.

“Yes rabbi, but emunah works many ways. The day the president told me about what happened, a deal which had been dead for years suddenly resurfaced and we did very well. So I have to thank you for this gift.”

The beautiful and spacious shul is testimony to the wisdom of building with emunah.

AREN’T OURS TO CHANGE

When the shul celebrated its expansion, Rav Shmuel Kamenetsky came and spoke. “He said that when the Ponevezher Rav visited Philadelphia, he liked to daven at our shul, because it was composed of bright, accomplished people — lawyers, scientists, doctors — who hadn’t studied in yeshivos, but they loved to learn Torah. That moved him.”

Along with being a learned congregation, the rabbi takes great pride that Lower Merion is a tolerant congregation.

“Not tolerant in matters of halachah, that isn’t ours to be tolerant with. We’ve faced many challenges from liberal congregations and groups over the years, and we’ve lost members as well, but I always tell my balabatim. ‘You make shul laws, so you can change them; but Hashem made these laws and they aren’t ours to change.’ ”

The tolerance he speaks of is the appreciation his congregants have developed for those with different minhagim and backgrounds.

“When we realized that we had enough Sephardic members to form a special minyan, there was resistance from some of our balabatim. They insisted that if we allowed a Sephardic minyan, the participants would never really be a part of the shul. I said, ‘We’ll make them a part, don’t worry, but not at the expense of their mesorah. That’s too precious to give up.’ ”

Today, the shul boasts several minyanim and all sorts of members.

“You know why? It isn’t just about ahavas Yisrael, though that helps too. It’s because the Torah belongs to every Jew and if Torah is the main product you’re selling, then it speaks to everyone.”

The shul’s letterhead boasts a two-word slogan; Torah Orah, and it was with that vision that the congregation faced its next major identity check, a process that could have been difficult, even destructive.

“I’m not as young as I look,” the rabbi says, laughing. “And it became clear to me that we needed a rabbi with the energy and youthfulness that this congregation deserves.”

This time, the shul, after yet another expansion, its membership flourishing, had no shortage of candidates.

DOESN’T DEFINE ME

“I made one plea to the people. I said, ‘Don’t embarrass me with your value system. Please show me that I taught you correctly and your priorities are right.’ I was so proud when they came to me and told me that they had hired ‘a real talmid chacham.’ They knew what I meant.”

The relationship between a rabbi emeritus and his successor can be the stuff of nightmares.

“Not here. The new rav, Rabbi Avrohom Shmidman is a genuine talmid chacham and a mentsh. He insists that I sit up alongside him, and begins his speeches by asking me reshus.”

But still, isn’t it hard for someone as personable as Rabbi Levene to hand over the pulpit?

“I didn’t say it was easy, I said it was right. I’ll tell you the truth; there are people who love their job and there are people who are defined by their job. I always felt privileged to serve in rabbanus, but it didn’t define me. I can still be a role model, I can still learn, and I can still teach, even without the title.”

Rabbi Avrohom Shmidman is unequivocal that the credit goes to Rabbi Levene. “How can someone nurture and build a kehillah from scratch, literally going from having no minyan to having the largest Orthodox congregation in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania? Only because he’s completely and totally l’Sheim Shamayim. It isn’t about him.”

“If he wants to speak, to address the congregation, he asks me for airtime!” Rabbi Shmidman says with wonder. “It’s a zechus to observe Rav Levene, because he elevates everyone around him.”

ONE FOR THE ROAD

Rabbi Levene walks me out of his home, urging me to accept his offer of sandwiches and a drink for the drive.

“You write, you deal with other Jews, let me leave you with a vort from the Zeide, Reb Aryeh.”

He straightens up, completely serious now. “He said that there are two mitzvos that seem to overlap, that of tochachah, giving mussar, and that of being dan l’kaf zechus, giving the benefit of the doubt. The Zeide said that really, tochachah should be used inwardly, a person should demand from himself and give mussar to himself. We should work to find zechusim in others. Today, the Zeide said, people tend to search for zechusim in themselves and use mussar just for others, they have it backwards....”

The smile that hasn’t waned for the better part of three hours is back. “Correct yourself, and look for the good in others.”

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 570)

Oops! We could not locate your form.