Lasting Impact

| November 30, 2021“Hashem, if you save my son, I will become completely observant,” he pleaded

As told by Rabbi Reuven Kigel to Ilana Kielson

Oh, my goodness, I realized. My nose is literally in the wrong place

It was a clear Monday night in March 1993 when we set off — me, my high school friend Jay, and an assortment of our college friends. Another car, also with some friends, led the way from University of Michigan in Ann Arbor, where I was a sophomore, to Windsor, Ontario, an hour’s drive away.

I wasn’t religious at the time, and my exposure to Torah-true Judaism was minimal. My parents, Jewish Russian immigrants, knew little about Yiddishkeit, though over the course of the last year, my father had started moving slowly toward Torah observance.

Soon enough, we were cruising up Interstate-94, a sprawling highway with four lanes in each direction. The atmosphere was relaxed — we had all just returned from spring break, and here we were, driving along, shooting the breeze, enjoying each other’s company.

What could be better? I thought, when suddenly — Hey, what’s that?

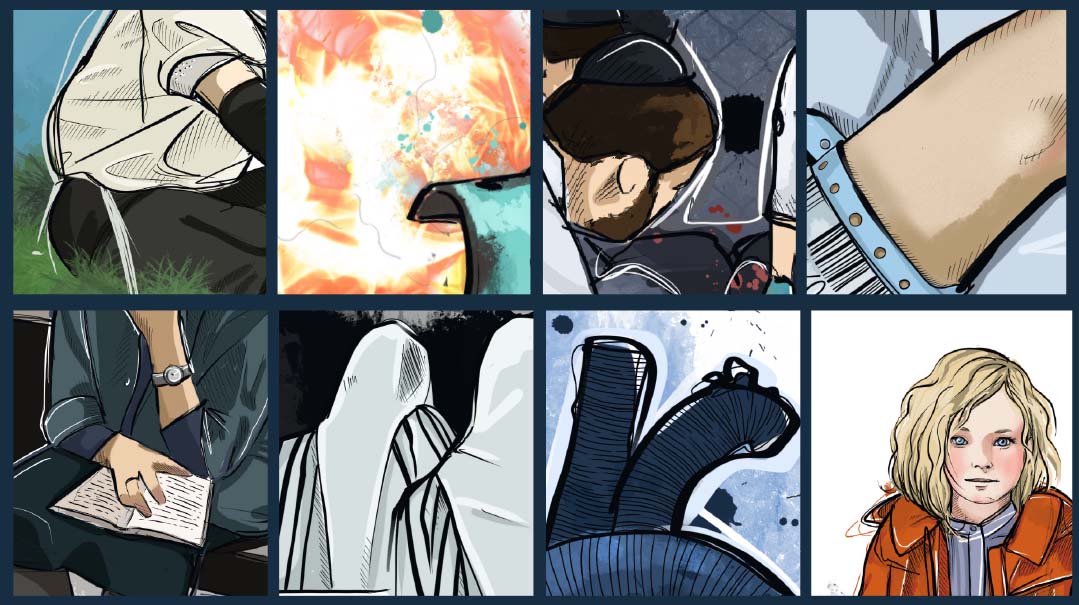

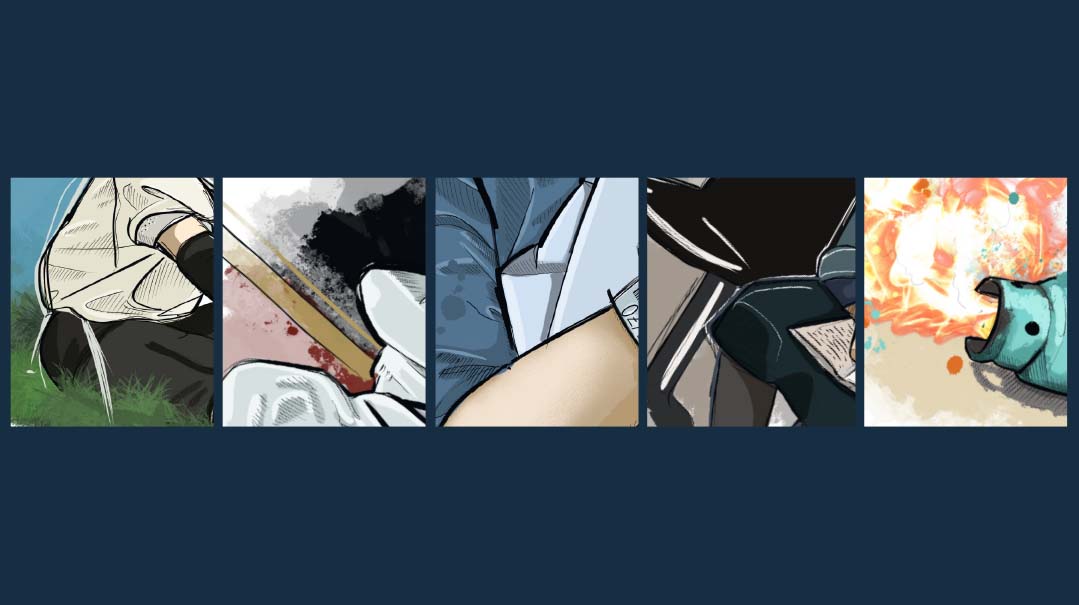

White lights, headlights — headlights! — were making their way straight for us. I had barely registered the sight when — BOOM! CRASH! — we were hit head on.

A drunk driver had swerved across the sloped grassy area dividing the two sides of the highway and into oncoming traffic — us — at full speed.

The impact was enormous. Both cars were traveling about 60 miles an hour. You do the math. That’s a collision force of a whopping 120 miles an hour. What’s more, the driver was behind the wheel of a Ford pickup truck. Our ‘93 Honda Accord didn’t stand a chance.

Oops! We could not locate your form.