Last One Standing

An observant Jew faced warlords and despots in risky territory, but never hid his Jewish identity

Photos: Eli Greengart, personal archives

The three-mile drive from Hamid Karzai International Airport to Afghanistan’s capital of Kabul is one of several roads in this war-torn central Asia country that bear the name Ambush Alley.

Ambush Alley has been the final journey for countless soldiers and civilians massacred in roadside attacks perpetrated by the Taliban, Al-Qaeda, or a host of local militias.

The road signs don’t warn you of the dangers. You must know the turf.

Dr. Elie Krakowski learned it well and has lived to tell his tales.

Dr. Krakowski — an Orthodox Jew, a Yeshiva University (YU) graduate, and a relative of both Rav Moshe Feinstein and Rav Joseph Ber Soloveitchik, zichronam livrachah — learned about the region and developed contacts in the 1980s, when he served as the Pentagon’s director for Central Asia during the Reagan administration.

That was a desk job, but he got his boots on the ground for the first time in the late 1990s, when he established a consulting firm to assist nations and private clients on security and political matters. Armed with a generous grant from a corporate sponsor, he embarked on a series of diplomatic forays into dangerous military zones in Afghanistan and its eastern neighbor Pakistan, to promote an elaborate and ambitious plan he developed for regional cooperation under US supervision.

His closest call on Ambush Alley came in 2001, just four months before 9/11. He arrived in a remote location in northeast Afghanistan near the Pakistan border. His host was the nefarious militiaman, Ahmad Shah Massoud, commander of Afghanistan’s Northern Alliance forces, who were fighting the Taliban.

“I landed there, and it turned out to be 14 miles from the front lines of the Taliban,” Dr. Krakowski recalled. “The day after I arrived, the Taliban attacked. We had to flee further inland to the Hindu Kush Mountains.”

Dr. Krakowski survived the visit, but he never saw Massoud again. Al-Qaeda assassinated Massoud two days before 9/11 in a suicide bombing ordered personally by Osama bin Laden.

Dr. Krakowski once told the Review, a YU alumni publication: “The work I do entails meeting with people in high-risk professions who sometimes meet their end in a violent manner.”

Dr. Krakowski experienced other close calls in Afghanistan on his first trip, three years earlier, when he met with Hamid Karzai, who later became Afghanistan’s president.

An armed convoy escorted him from the airport to spartan accommodations that consisted of a sleeping bag cushioned by just a thin mat. Guards armed with machine guns patrolled around the clock to keep insurgents away, but they couldn’t do much to rein in the local snake, scorpion, and rat population. While both Dr. Krakowski and Karzai survived that visit, Taliban agents assassinated Karzai’s father a few months later.

Even though 20 years have passed since his dangerous journeys, which also took him to Iran, I’m astonished by the matter-of-fact way Dr. Krakowski speaks. Well-educated in both Torah and geopolitics, he neither overplays nor underplays the drama of his travels. He says he never thought about being afraid until other people mentioned he should be, and at most, he admits to having underestimated the risks.

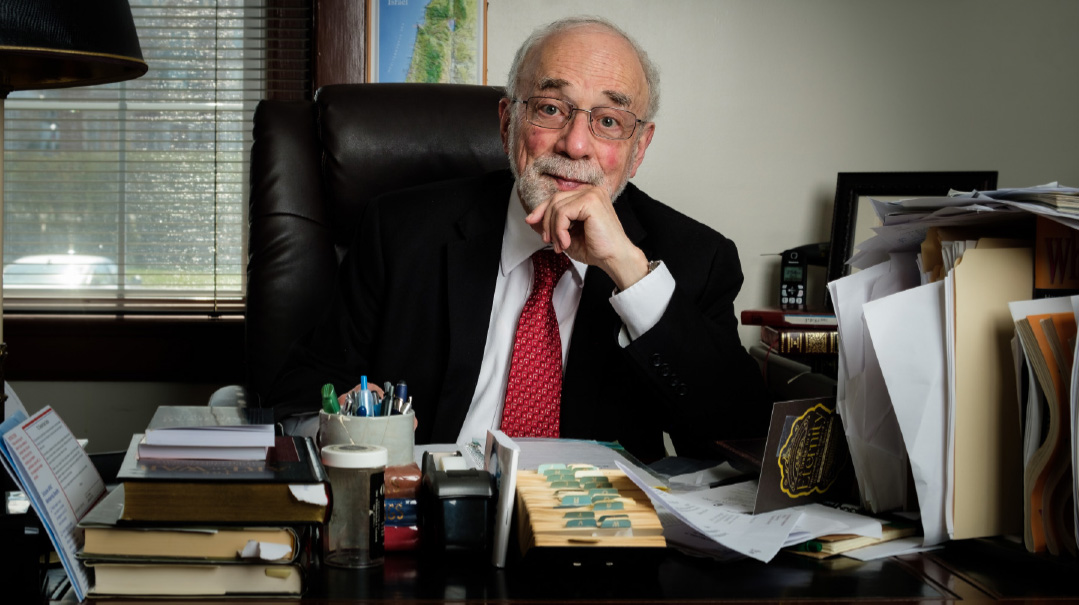

“By all normal means, I shouldn’t be here talking to you today,” he says as he sits comfortably in an office chair in his study.

Behind him is a map of Biblical Israel showing the division of the land by tribes, and to his right is a map of Israel in relief, along with some family pictures on overhead shelves.

“It is a bit unique. If I’d been told when I was 20 years old that I would end up doing all the things I have done, I would have told them they were completely crazy. Why would a nice Jewish boy be doing those things? This is what I can tell you — it’s all Hashgachah pratit and siyata d’Shmaya. I was in dangerous situations, but I actually thought that there was something important that I needed to do, and to do it, I had to go to these places.”

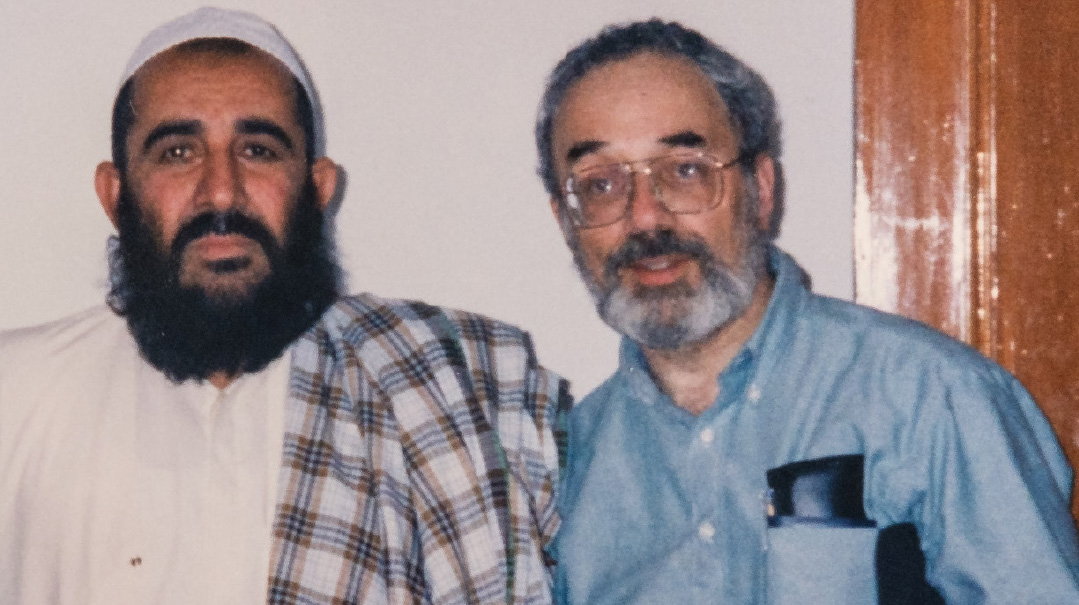

With a former Taliban leader in Pakistan during a fact-finding mission in the summer of 1998

Between 1998 and 2009, Dr. Krakowski traveled to Turkmenistan, Tajikistan, Uzbekistan, Iran, India, Turkey, Russia, Azerbaijan, and China, generally for one to three weeks at a time. The visit to Iran lasted five days.

His wife prepared all of the food he needed for those long hauls. “She made sure I wouldn’t go hungry, but I usually did lose some weight on those trips,” he said.

His wife wasn’t scared, nor did he fear for his life. “I assured my wife that it was safe, and she trusted me,” he said. “There may be something genetic there as well: my grandfather and great-grandfather were involved in dangerous situations that required great courage in confronting Russian or Polish authorities in their time. They were never afraid, as they considered action to be their duty.

“I took precautions, but the truth of the matter is, I probably did not realize fully the extent of the danger,” Dr. Krakowski concedes. “I knew it wasn’t exactly a picnic. To go into Pakistan, for example, except the first time I went in 1998, no Western airlines were flying into Pakistan anymore because the danger of terrorism was too high.”

His contacts advised him to arrange his visits through local Pakistani think tanks, which were usually fronts for various security agencies, and ask them to organize his itinerary.

To the best of their capabilities, they assured his safety, providing him with a car and driver, but also warned he would be shadowed. “I also remember them telling me to avoid Karachi at any cost, as the security apparatus there had been penetrated by extremists,” Dr. Krakowski said. “My being a Jew and an American meant I was at risk of being kidnapped, tortured, and killed. Needless to say, I avoided the port of Karachi.”

Aside from his immediate family, a few close friends, key officers of the granting foundation, and the officials in countries to be visited, no one else knew his whereabouts. Dr. Krakowski always made sure in advance of his visits to speak with people he knew well and trusted, and who were also knowledgeable about current conditions.

“I would ask how safe it was to go there, how I should proceed with arranging the trip, where I should and should not go, and with whom I should deal or avoid dealing,” he explained.

Since most of his meetings and negotiations were government-related, he made sure never to go behind the backs of local officials, and would only visit with their express consent, or by invitation.

Aside from exhibiting physical fortitude, he often found himself displaying verbal courage, never backing down from wrangling with his Islamic interlocutors, especially when they challenged him with anti-Semitic canards and anti-Israel sentiment.

“I don’t have patience when people attack,” Dr. Krakowski said. “If they want to learn, then I’m more than happy to try to explain. But if they are attacking, they pick the wrong person by doing it with me. Because I am proud of who I am.”

With Commander Ahmed Shah Massoud, leader of Northern Alliance forces fighting the Taliban, northeast Afghanistan, April 2001. Some four months later, he was assassinated by Al Qaeda in the very same location

Not One Bit Shy

Part of who Elie Krakowski became can be attributed to his chinuch and strong formal education.

When he arrived in the US, he enrolled in YU High School and continued in the system, earning a bachelor’s degree from Yeshiva University at age 20. While most YU undergrads in those days were premed or prelaw students, Elie broke the mold.

He had taken a philosophy course at YU and felt drawn to it. He also took a course in political theory, but found that to be too esoteric. He found another course in international relations to be of interest, but not theoretical enough.

He continued his intellectual exploration at Johns Hopkins School of Advanced International Studies, where he earned a master’s degree in international relations and law. He earned another master’s in philosophy and a PhD in political science and government at Columbia University, where he completed his doctoral dissertation under the tutelage of Zbigniew Brzezinski, President Carter’s one-time national security advisor.

The Polish-born Brzezinski played a key role in negotiating the 1978 Camp David Peace Treaty between Israel and Egypt. There’s a famous picture from Camp David showing Zbig, as he was known, playing chess with Israeli prime minister Menachem Begin. But Brzezinski was also the man who once said that if Israel were to ever attack Iran, the US should shoot the Israeli jets out of the sky.

While fellow students warned Krakowski that Brzezinski was impatient with students and too demanding, Dr. Krakowski carved out his own relationship with Zbig.

“It was interesting with him, because he had a reputation of being anti-Semitic,” Dr. Krakowski said. “However, on a personal level, he liked me very much.”

A couple of years after the Camp David summit, when Dr. Krakowski was working on his thesis, Brzezinski corralled him in the hallway and showed him an article Begin had written about him in the Hebrew-language press.

“I want to know what Begin says about me, can you translate?” Brzezinski asked.

“I was a little bit apprehensive,” Dr. Krakowski said, “but it turned out to be fairly positive. I translated for him, and he was very pleased.”

From then on, Brzezinski would often utilize Dr. Krakowski as a source on Israel.

Dr. Krakowski recalls one conversation when Brzezinski went on a rant that Israelis were being suicidally rigid in their insistence on keeping the parts of Judea and Samaria that they conquered in 1967. After letting him vent, Dr. Krakowski asked Brzezinski if he was interested in his opinion.

“And he said, ‘Oh, yes.’

“So I said, ‘Let me give it to you in three parts. Number one, you know that I am an Orthodox Jew. We happen to believe that we will be the last ones left standing and that ultimately, we will win.’ I said, ‘You don’t have to believe this but it’s a factor in the equation.’

“ ‘Second,’ I said, ‘at every turn in the history of modern Israel, people say Israel cannot continue to exist. The UN [1947 partition] resolution, with its three-point division [into Israel, Palestine, and Gaza] was a one-factor analysis. It didn’t take into consideration other factors, and it has been proven wrong time and again.’

“And thirdly, since he had been a main player in the Camp David negotiations, I said, ‘With regard to the Israeli rigidity, you know very well that when Egypt was willing to sign a peace treaty, Israel gave up everything that was taken from the Egyptians [the Sinai Peninsula]. So this [treaty] is a piece of paper that can be taken back, but the territory that Israel gave back is not so easy to undo. So, when we talk about flexibility, I think you should really be concerned about the Arabs, not Israel.’ ”

To which Brzezinski replied,

“Yes, you’re right.”

Did he agree with you, I ask.

“Yes, but probably not for very long.”

Looking back, Dr. Krakowski frames their conversation as follows: “Being who I was, I was never shy. The fact that he was prominent didn’t faze me a bit, and I always told him exactly what I thought, which was often very much at odds with what he was saying.”

Brzezinski even agreed to serve as a reference on Dr. Krakowski’s résumé. “I have letters from Brzezinski complimenting me on my writing,” Dr. Krakowski said. “I have a book from him that he inscribed with strong, fairly complimentary language about what he thought of me.”

Afghanistan was a land of terror and strife, but also of diplomatic opportunity. Could his plan position the US in the driver’s seat?

DR. Krakowski was teaching at Yeshiva University when he applied for a job vacancy in the Department of Defense. “I was happy teaching. I was happy doing research. Why did I have to look for anything else? But the Al-mighty, I guess, had other designs.”

He had researched how to fight propaganda wars, and this took on added importance at the time. It was 1982, about halfway through President Reagan’s first term. The US was about to deploy intermediate-range ballistic missiles in Europe to counter the Soviet threat, and the Soviets had mounted a major propaganda campaign.

Dr. Krakowski can’t be certain that having Brzezinski’s name on his résumé got him in the door, but he does remember clearly that an Air Force general interviewed him and hired him ten minutes into the interview. His career was underway.

His job was to offer policy options and crunch the various pros and cons of each course. “I had a pretty good track record in terms of forecasting, and this got me into trouble more than once in terms of my telling people things they don’t want to hear,” Dr. Krakowski said.

After one clash with his boss, he knew he was in trouble. “He decided that Krakowski is history.”

Dr. Krakowski was halfway through a one-year contract, but he had just bought a home assuming the government offered good job security. Dr. Krakowski knew how to play the game, and had made sure to bring his work to the attention of higher-ups in the defense department, the most senior of whom was Richard Perle.

Even then, Perle, who served as Reagan’s assistant secretary of defense, was a Washington legend. Perle was an important leader of the neo-conservative movement, whose adherents strongly opposed Communism and advocated the use of US power to achieve foreign policy goals. A dyed-in-the-wool foreign policy hawk nicknamed the “Prince of Darkness,” Perle was Jewish, not Orthodox, but Dr. Krakowski recalled that on his work calendar, he had marked Pesach and Rosh Hashanah as days off.

Once he learned that Dr. Krakowski was having a conflict with his supervisor, Perle offered him a job as his special assistant, reporting directly to him. Dr. Krakowski eagerly accepted the promotion.

“That is why I said to you at the beginning, about Hashgachah pratit and siyata d’Shmaya. This happened a number of times in my career, where I did my job, people became a little jealous and tried to do me in. Each time, it rebounded to my benefit.”

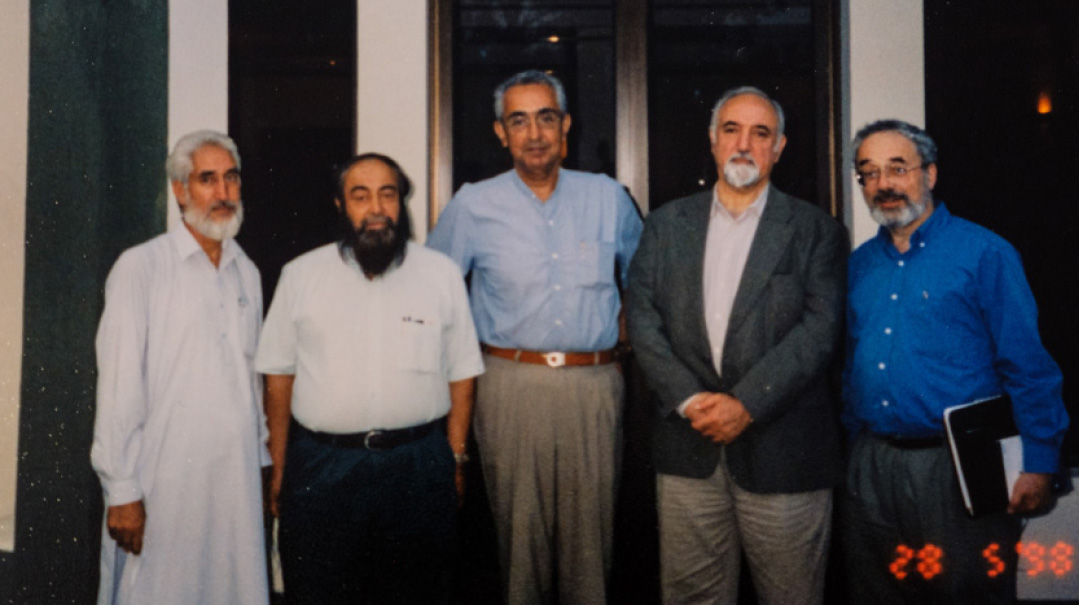

Slowly building consensus for a bold, creative plan. In front of Turkmenistan Parliament, December 2000; with Afghan religious and military leaders at the Pakistani-Afghan border, June 1998

The Master Plan

His formal title became special assistant to the assistant secretary, responsible for countering Soviet activities in the Third World. Afghanistan quickly became his focus.

The Soviet Union invaded Afghanistan in 1979 to prop up the pro-Moscow government that had seized power in a military coup. The Soviet invasion of its southern neighbor transformed a longstanding national conflict into another Cold War hotspot.

Reagan was determined to trigger the collapse of the Soviet Union in any way he could. Providing US military aid to anti-Soviet Afghan rebels became one arm of his policy.

At first, Dr. Krakowski was convinced that the Soviets could be forced by military means to withdraw their troops from Afghanistan. And he was partially right; American pressure did help make life miserable for Soviet troops, who eventually quit Afghanistan in 1989 under a UN-sponsored treaty.

Dr. Krakowski left the Defense Department in June 1988, as the Reagan administration’s final term was winding down. He spent the next seven years as an associate professor of international relations and law at Boston University, but never lost interest in the region he was responsible for during his Pentagon stint.

After the Soviet withdrawal, Afghanistan became a far more dangerous place. The Taliban seized control of most of the country, including Kabul, and imposed Islamic law, forbidding women to work, and carrying out public executions, beatings, and amputations. Al-Qaeda also set up shop in Afghanistan and used that as a base from which to attack US embassies in Kenya and Tanzania. The US responded with cruise missile attacks on Al-Qaeda strongholds in Afghanistan.

Dr. Krakowski continued to follow regional development with keen interest and deep concern. He published many articles that were widely circulated in professional and government circles, testified before Congress, and was often interviewed in the mainstream media. In 1997, he granted a lengthy and comprehensive interview to the National Security Archives, a project of George Washington University entitled “Soldiers of G-d,” which contained the seeds of his next major professional challenge.

“What I was seeing at the time — and things haven’t changed much — was a lack of a coherent strategy with regard not only to Afghanistan but to the whole region surrounding it,” Dr. Krakowski said. “My belief was that it was possible to replace the Taliban with a more representative government, and simultaneously improve the situation in the entire region.”

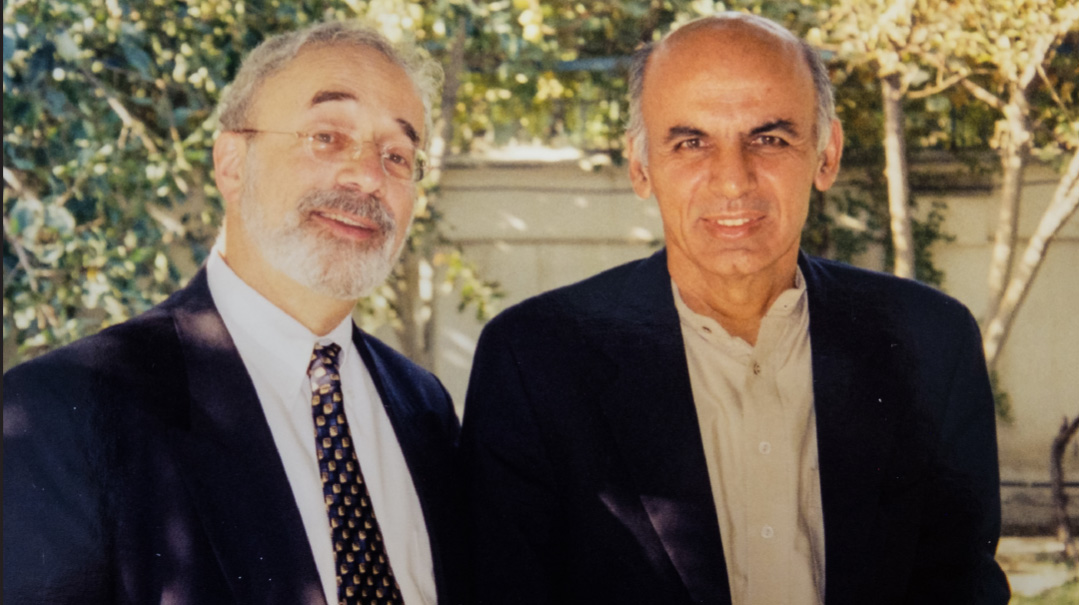

I found that America was too risk-averse to take the bold steps that were needed. With Ashraf Ghani, then Minister of Finances, later President of Afghanistan, in Kabul of 2003

With his knowledge, experience, and no small measure of daring, he set about laying the groundwork for a new diplomatic model in a region of clashing interests and convoluted alliances. What concerned him most was the interference and promotion of strife by neighboring states looking to maximize their power and prestige, carving out or protecting their interests at Afghanistan’s expense.

“I developed a very comprehensive strategy that would place Washington in the ‘driver’s seat’ while ensuring that all states would be enabled to achieve what were their legitimate interests there,” Dr. Krakowski said.

The next step in his process was to test the regional acceptability of his strategy by going to the various interested parties and conducting informal negotiations. Thanks to his stint at the Defense Department, to the contacts he made and retained, and to his published works, he was no stranger to the various players.

No longer hindered by government bureaucracy and political machinations, he embarked on a private mission to Afghanistan, funded with a generous corporate grant from the Smith Richardson Foundation, which helps institutions develop effective policies to advance US interests abroad.

He soon found himself holding meetings with foreign governments at high levels, including Russia and China. “I was a known entity, and I had a certain reputation,” he said. “My sense is that officials in those countries didn’t believe my project was ‘just a research project’ but a trial balloon from very high up [in US government circles] to see what those various countries would say and do.”

Having said that, for the most part, Dr. Krakowski kept US officials in the dark about his shuttle diplomacy.

“The US government tends to be kind of impervious to ideas and grand strategy, but I figured that if I did it on my own and tested out with the various countries whether they would play along, then I could bring it to the US with 60 percent of the work done, and maybe it would be accepted,” Dr. Krakowski said. “I don’t need to tell you that it was an extremely ambitious idea, but this is how I think — in large terms.”

This project eventually brought him to ten different nations. In Pakistan, in particular, he held lengthy discussions with the foreign minister, the deputy defense minister, and top military intelligence officials.

Even though he never overtly told his hosts that he was Jewish, an Orthodox Jew in a predominantly Islamic country can’t hide his identity for long.

Toward the end of one meeting, a top Pakistani official remarked: “Israel cannot continue to exist for much longer.”

“It had nothing to do with anything in the conversation,” Dr. Krakowski remembers. “I knew then that he knew that I was a Jew and he wanted to make a dig. So I said, ‘Tell me, do you know history?’ He was a bit surprised, but he said yes. So I said, ‘Well, then, you should know that there are many nations and people that have come and gone, and they are not here anymore. The Jews, even after 2,000 years without their state, are still here. And they will be the last ones left standing.’ ”

What was his reaction?

“He opened his mouth and nothing came out. And then I left.”

Help Wanted: An Orthodox Jew

He had a similar experience in Pakistan with Hamid Gul, who served as director-general of Pakistan’s notorious Inter-Services Intelligence.

In January 2001, Gul was one of 300 leaders representing various Islamic groups at a conference near Peshawar, who declared it a religious duty of Muslims worldwide to protect what they called the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan and the “great Muslim warrior,” Osama bin Laden.

Dr. Krakowski would not have been the least bit surprised by that declaration, considering he had met with Gul two months earlier, in November 2000. The outcome of America’s presidential election was still in doubt due to a vote-counting dispute in Florida, but had Al Gore been named the victor, his running mate, Joseph Lieberman, would have become America’s first Jewish vice president.

“I barely sat down and he [Gul] starts on an anti-Semitic rant, that the Jews are power hungry and greedy, and Lieberman’s candidacy as a vice president is not just that [to become VP], he wants it all,” Dr. Krakowski recalls. “I don’t take that kind of thing very kindly, to put it mildly, so my face must have gone through several color changes. After about a minute and a half of this rant, he points to me and says, ‘Where are you from?’ I said I’m from the United States. He says, ‘No, no, your religion, your ethnic background.’

“I said, well, if he wants to know, I’ll tell him, so I said, ‘I’m a Jew.’ His facial spasm was visible.

“And almost without blinking, he again pointed with his finger: ‘Are you Orthodox, Conservative, or Reform?’

“I said, ‘Oh, you know about that?’

“And he said, ‘Yes, never mind, which one are you?’ I told him I was Orthodox.

“ ‘Ah,’ he said. ‘For a long time I’ve wanted to talk to an Orthodox Jew.’

“I said, ‘Okay, here I am.’

“He says, ‘You know, Jerusalem is not a political question, it’s a religious question.’

“I said, ‘You know what? I agree with you. Now let me tell you what I think. I think Muslims are doing the wrong thing.’ And his eyes start to flash like charcoals. I said, ‘Yes, if they wanted to do the right thing, they would recognize that Israel is here to stay and recognize Israel.’ And then I said, ‘Violence is not going to solve this issue. If they do what I am telling you [to recognize Israel], I guarantee you that in six months, you’d have an agreement.’

“He said, ‘You’re absolutely right, and it’s not only that, the [PA] government doesn’t represent the Muslims.’ After that, we had a perfectly friendly conversation on the subject I came to discuss.”

Dr. Krakowski was aware that his clear and direct language could backfire on him when dealing with despots and tyrants, but he contends that you can’t just ignore the many nations that are ruled by despots and tyrants.

“One doesn’t gain any points by engaging in insults, but one also doesn’t gain any points by saying I don’t want to talk to them,” Dr. Krakowski said. “It doesn’t mean you have to like them or approve of them. In my case, I can tell you I have never lied. I might not have said everything. There is a difference between lying and not saying everything. So with [certain] people, I told them to their face that I think they are wrong in the things they pursue, and I told them why they are wrong.”

DR. Krakowski experienced déjà vu when he arrived in Iran to present his plan at a conference in December 2003. Attendance at a conference was one of the few ways for an American to receive an entrance visa. He had coordinated his visit over nine months earlier with Iran’s UN ambassador. Dr. Krakowski never informed the US government, fearing they would “interfere” if they got word of it.

He was pleasantly surprised that the Iranians let him in, even though his US passport had stamps from visits to Israel.

The Iranians also believe in a worldwide Jewish conspiracy to control the world, and in this case, he thought he could play on their fears to his advantage.

He made sure the Iranians were aware of his connection to prominent Jews such as Richard Perle, and even Paul Wolfowitz, who at the time was George W. Bush’s deputy secretary of defense. Dr. Krakowski was also doing some consulting work for Wolfowitz, although that work was totally unrelated to the Smith Richardson grant project.

“The Iranians knew my connections, and I made sure they would be aware of that,” Dr. Krakowski said. “I decided that I’m going to behave as if I’m an important member of that conspiracy and they better deal with me. It seemed to work.”

While he didn’t advertise his Jewishness, he informed his hosts that he would be unavailable Friday afternoon after a certain time, and most of Saturday.

In Iran, he met with the deputy foreign minister, editors of the leading newspapers, and a top aide to former president Hashemi Rafsanjani.

At the conference, a Lebanese professor approached him to ask a question.

“I don’t know who he was, but I said, sure. He said, ‘Tell me, is it true that when the Jews bake their matzah for Passover, they use the blood of a Christian child?’”

Dr. Krakowski acted insulted. “I said to him, ‘Tell me, you are an educated man, aren’t you?’ He said yeah. And I said, ‘And you believe that garbage?’

“He said, ‘Well, not really, but I thought I would ask.’ Then he walked away.”

Aside from the “Jewish conspiracy,” what unnerved Iran was the regional geopolitical situation. American troops were fighting President Bush’s war on terror on Iran’s eastern and western borders, in Iraq and Afghanistan. The Iranians were afraid they were next on Bush’s list.

When asked why the US was so preoccupied with Iran’s nuclear development program, and ignored Israel’s, Dr. Krakowski said it’s not the weapons, it’s who’s wielding them.

“Israel,” he said, “is not a government like yours, which subverts its neighbors and supports terrorism and has said they would attack Israel with nuclear weapons if they had them. ”

The Iranians pushed back on this and said that Iranian president Ahmadinejad had been misinterpreted and never meant to threaten Israel with nuclear weapons. Today, this is Iran’s official line, even if no one believes it.

When the Iranians noted that there was little they could do, since they had no diplomatic relations with the US, Dr. Krakowski said that the US would view Iran differently if they would stop supporting terror, carry out internal reforms, and recognized Israel.

All of this would render Iran’s Islamic Revolutionary Government irrelevant, so Dr. Krakowski understood his suggestions were nonstarters, but today as well, he says that both the US and Israel should be pointing this out.

“We have to be more forthright,” Dr. Krakowski said. “We have to be more willing to say things as they are.”

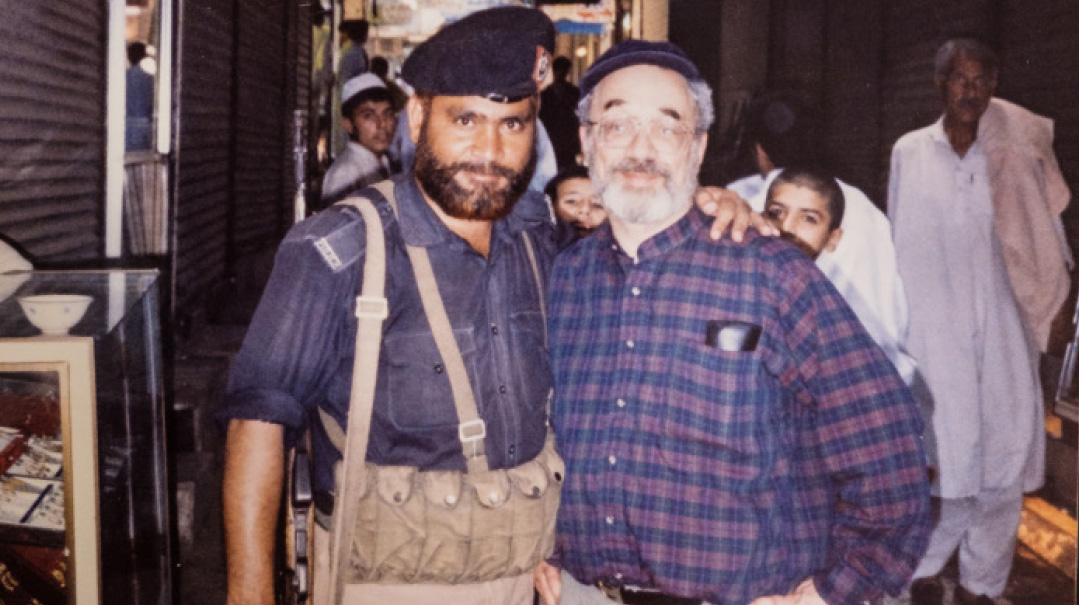

“You don’t gain from evading the truth.” Dr. Krakowski found the direct approach was often smartest in building alliances with suspicious sources. On a Pakistan fact-finding mission in 1998, he met up with a prominent Afghan exile and a US Embassy official in Islamabad; and in an April 2001 he traveled with two Afghan generals on a road trip from Uzbekistan to Tajikistan to Afghan Commander Massoud

Measuring Success

Dr. Krakowski invested five years of his professional life on this project that never came to fruition, even though he insists that every country he dealt with, including Russia, expressed serious interest. In the end, it was the US government, at fairly high-level echelons of the Pentagon and the National Security Council, that was unwilling to buy in, although Dr. Krakowski said that they gave him a fair shot at making his presentation.

One major objection centered on dealing with local warlords he had met, such as Afghanistan’s Ahmed Shah Massoud. It grew clear to Dr. Krakowski that America is risk-averse and doesn’t want to deal with bad actors, even if they are the only ones left standing on the stage.

“I said, ‘You don’t have to marry the guy, just work with him’ — and ultimately, we had to [after 9/11],” Dr. Krakowski said. “You have to confront them, and there are ways to confront them. I was able to confront people who I knew had blood on their hands and talk to them. Negotiating means dealing with reality, and trying to get the best deal you can, and in my case, it meant also not compromising on principles.

“What I have done in my career has been to try to minimize conflict, to try to minimize killing, wherever it is — but at the same time to stick to a certain principle, which is that the West is superior in terms of its moral content, or certainly was until not long ago. Now it’s become more of a question, but it still has that standing.”

To this day, he has no regrets, even though his grand project never came to fruition. “My motivation for doing all this and spending so much time on it was that I thought I had a practical, significant contribution to make, and that by doing a very substantial part of the work needed — including showing evidence of the strategy’s receptivity by all parties concerned — I was ensuring a greater likelihood of its being adopted as policy. Unfortunately, this did not occur.”

While he was disappointed with this failure, he is proud of two crucial accomplishments he can take credit for on the foreign policy front when he worked for the Defense Department.

The first was in Afghanistan, in 1985, when the Russians offered to withdraw from Afghanistan over four years but demanded that the US stop providing military aid to the Afghans from day one of the withdrawal.

This was a ploy that would have left the Afghan rebels the US was aiding dangerously exposed.

Dr. Krakowski learned from sources he had cultivated in the State Department that they were willing to agree to the Soviet proposal, and he realized the only way to stop it was to expose it.

He approached the conservative Heritage Foundation with a prepared speech and invited the Washington press corps to attend. Dr. Krakowski was careful just to expose the Soviet ploy without implicating the State Department. His strategy worked. The next day, his speech made front-page news at the Washington Post, and other global media outlets picked it up.

“It killed the Soviet deal — it never came to be,” Dr. Krakowski said.

Perhaps his most important and long-lasting accomplishment was alerting Congress that the Pentagon was ill-equipped to deal with low-intensity conflicts, such as small wars, guerrilla warfare, and terrorism. He proposed that the defense establishment create an interagency organization to deal with this and follow through.

To build support, he visited Capitol Hill and met with key members of Congress, but before he could brief his boss, Richard Perle, someone leaked the idea.

“I said, oh, my goodness, now I have a problem, because I had been told never to let your boss hear what you’re doing from somebody else. He should hear it from you.”

Dr. Krakowski sought an urgent damage control meeting with Perle, who told his underling that he had indeed heard about it at a press briefing, but he was busy, and asked if he could come back later.

“He didn’t seem too upset,” Dr. Krakowski recalls. “So later, I come back, and he’s with one of his deputies. He sees me coming into the room, and he says to the deputy, ‘Look at this. We’re trying to get $100 million for the contras, and Elie here is already up to $500 million [for his project].”

The Prince of Darkness turned magnanimous on this one, and ultimately, Dr. Krakowski’s project morphed into something much bigger and long-lasting — the 1986 Goldwater-Nichols Defense Reform Act, which improved the ability of US armed forces to conduct joint (interservice) and combined (interallied) operations in the field, and also helped improve the Department of Defense budget process.

“It was much bigger than what I had initially contemplated,” Dr. Krakowski said. “It created an assistant secretary for low-intensity conflict, among other things, in the Pentagon, which to this day exists. I don’t claim that that it’s my thing alone, but I triggered the thing and got it going.”

Another one of Dr. Krakowski’s projects enabled Afghan rebels fighting Soviet forces to acquire mine-clearing equipment. Over the years, more than 40,000 Afghanis, including more than 25,000 children, had been killed by land mines laid by various combatants.

Once safely home from his foreign travels, Dr. Krakowski devoted more time to EDK Consulting, a company he first established in 1996 to offer both corporate and government clients a blend of his talents, including strategic consulting, unique analytical capabilities, and the integration of high-tech products geared to fighting the global threat of terrorism.

He landed equipment deployment contracts for a number of Homeland Security and counter-terrorism issues with a variety of federal and state government agencies, one of which enabled the Baltimore Police Department to enhance its night vision capabilities to conduct surveillance on boats in the Baltimore Harbor.

Dr. Krakowski spends most of his time close to home in Baltimore, where he has affiliated with Congregation Bnai Jacob Shaarei Zion in the heart of Baltimore’s Orthodox Jewish community.

He is focused on writing his memoirs and finishing a 420-page manuscript on the development of warfare during the 20th century, which he finished in 1996 but remains unpublished.

“One of my many flaws is perfectionism,” Dr. Krakowski said. “I was not happy with a couple of chapters. Now I think I should get back to it, but it’s a major amount of work.”

He and his wife Silvia Krakowski raised four daughters and two sons. Silvia holds a master’s degree in educational psychology, but after working early in their marriage, she mainly stayed home to raise the children.

All of their children are married with families of their own, and many of them also hold advanced degrees. One son, Rabbi Yissachar Dov Krakowski, named after Dr. Krakowski’s father, is the director of OU Kashrus in Israel. In that post, the apple hasn’t fallen far from the tree, as his work often takes him to Dubai, Abu Dhabi, and Bahrain. One of his sons-in-law is Rabbi Mordechai Weiskopf, an editor at ArtScroll.

He still follows international affairs closely, and while his emunah has always guided his work, he sees more than ever now that world affairs are in the Hands of the Al-mighty.

“One has to be blind not to see that His Hand is now very visible, because the kinds of things that are happening cannot be explained by regular interpretation,” Dr. Krakowski said.

“When people ask me what can we do, I tell them two things. One is to daven very hard, and the other one is to improve oneself. If we all improve ourselves, we can change the situation in a very major way. I’m not saying anything new. This is all over the Torah, that we have certain obligations, and if we don’t do them, there are certain consequences.

“So while I can explain the types of [geopolitical events] that are happening down here, ultimately, it all goes back to the fact that it is G-d who runs the world. Something very large is happening in the world, and I hope that somehow, things will become better.” —

A Gadol Never Slows Down

Dr. Krakowski inherited a calm and dignified demeanor from the prominent rabbinic family he was born into.

His grandfather was Rabbi Menachem Krakowski. Born in the Lithuanian shtetl of Vilkovishk, he learned in the famed Volozhin yeshivah and served as a community rabbi in Minsk and Russia before World War I. He is the author of the sefer Avodas Hamelech, a commentary on the Rambam’s Sefer Hamada.

Dr. Krakowski’s father, Yissachar Dov Ber, also had semichah, along with doctorates in philosophy and literature. His mother Anna was well-versed in Tanach, spoke seven languages, and held a doctorate from the Sorbonne in French literature. His parents met when they were both studying in France before World War II. Married before the war broke out, they eventually crossed into Switzerland after the pro-Nazi Vichy government took control of France. His mother taught Tanach in France, and when the Krakowskis moved to the US in the early 1960s, when Elie was 14, she continued teaching Tanach and French literature at Stern College.

The move to the US almost never happened. Elie’s father had taken a “pilot trip” to America after World War II. Dr. Krakowski recalled the initial family deliberations.

“When he came back, my mother said, ‘So, how was it?’

“My father said, ‘It’s not for us.’ ”

When she asked why, his father replied, “In America, when they ask how much someone is earning, they say, ‘How much is this man worth?’ He said a society where people think like that is not for us. That was my father. Very humble and always focused on middos.”

However, his father’s health had taken a turn for the worse. When Dr. Krakowski was seven, he witnessed his father suffering a heart attack. He was sick for the next two years, and passed away when Elie was just nine and a half.

Before he left this world, his father told Elie’s mother that maybe America would be a good idea after all, because the chinuch was much better there. While it was difficult for Mrs. Krakowski to abandon her career, and she was prominent in both the Jewish community and in the broader professional world, she uprooted herself for the sake of the children.

“My parents were very special people and role models for me,” Dr. Krakowski said.

His parents were also a unique case of two first cousins who married each other. The mothers of each of his parents were daughters of Rav Elya Feinstein ztz”l, also known as Rav Elya Pruzhaner. Elie is a second cousin, once removed, to Rav Moshe Feinstein, and a first cousin, once removed, to Rav Joseph Ber Soloveitchik. Both attended Elie’s wedding to Silvia Wetzler, and Rav Moshe was their mesader kiddushin.

Dr. Krakowski’s mother had developed a close and trusting relationship with Rav Moshe and his wife, and Elie has fond memories of frequent Sunday lunches with the Feinsteins at their Lower East Side apartment.

Dr. Krakowski relates that once, when Rav Moshe was already up in years, Rebbetzin Feinstein asked Dr. Krakowski’s mother to suggest to Rav Moshe that he needed to slow down, and that maybe the Rav might listen to her because he respected her.

“So when we came for lunch,” Dr. Krakowski said, “Rav Moshe sat at the head of the table. My mother was always to his left. As we sit down, he turns to my mother and says, ‘I understand you want to talk to me?’ Before my mother could say anything, he points to his wife at the other end of the table and says, ‘She doesn’t understand. I cannot slow down. I am here for other people.’ ”

Before he got married in 1975, Dr. Krakowski reached out to Rav Moshe for some advice. He had to visit personally, because there had been a fire in the neighborhood and the phone lines were down. Dr. Krakowski commented to the Rav that maybe now he could slow down a bit, as the calls that would normally come in from all over the world were temporarily interrupted.

Rav Moshe viewed things differently.

“He said, ‘When the phones work, people know I’m very busy, so they understand I can’t talk longer than three or four minutes. But when the phones are down, when a Jew comes to the door, you let him in. You ask him to sit down and have a glass of tea and some cookies. This takes more time!’ ”

Whatever personal advice Dr. Krakowski obtained, he walked away from Rav Moshe’s house that day with a greater lesson: the humility of a gadol hador.

“A man like that didn’t have a concept that he could be selective. A Jew comes to his door. He has to deal with him, he has to answer his questions, he has to give him tea and cookies.”

Spinning Things Forward

Dr. Elie Krakowski’s career in geopolitics has spanned four decades, and while the world has changed in dramatic ways, much remains the same.

Russia has supplanted the Soviet Union, but Russia is just as aggressive militarily as the Soviets were. Iran has become a growing menace more than 40 years after its Islamic Revolution, and the United States might still be the world’s biggest superpower on paper, but it often acts more like a paper tiger.

I asked Dr. Krakowski a few specific questions to put some of his experience into a greater context, and to spin his experiences forward to analyze some major current events. The conversation was edited for length and clarity.

Is there something in the American DNA, in the higher levels of the State Department or the Pentagon, that prevents them from seeing the world as it is, or is the world too big for them, even with all the resources they have?

“I came into the government thinking we would have interagency meetings to discuss the merits of various options and strategies. In my experience, and I was there for the two Reagan administrations, we had very little discussion.

“Here I talk from personal experience. I very often had a hard time convincing people to do what I thought was the right thing. And I believe quite firmly that what I have accomplished that has been constructive, has been by going around the system, not through the system. In the meetings, I was told, ‘We don’t want to do that.’ Why not? ‘It would send the wrong signal at this time.’ Why the wrong signal? Why at this time? No explanations.

“And people have previous positions and vested interests that build. Even when they see it’s bad, they don’t let you get out of it. So this is something that I myself have always struggled to understand, because I think we have all the resources that we need. The government is a very big place with a lot of people. It’s not one person dealing with everything. Certain behaviors have developed over time, and in any bureaucracy, there is a certain inertia. People don’t like to do on Tuesday anything materially different from Monday. They also don’t like risk. Risk means more work; it means more complicated things that you have to deal with.”

In March 1993, when you were teaching at Boston University, you appeared at a forum at Harvard’s Kennedy School of Government titled, “Are We Still Safe from Terrorism?” This was right after the first World Trade Center bombing, when terrorists detonated a van bomb in an underground garage. On that panel, you noted that Iran believes that the US had relegated terrorism to a secondary position from a policy and action standpoint, and they don’t go much further than to try and catch immediate culprits. In that vein, you said the US was signaling to Iran it was very timid in terms of pursuing its agenda in the Middle East. That was rather prescient. How do you see that today?

“I think it’s even worse today than it was then. In this administration, the people who are in charge of dealing with Iran, like Robert Malley, are actually quite favorable to the Iranian regime. They have bent over backward to appease and refrain from antagonizing. What I am about to say is not anything new, that the US is behaving toward enemies in a friendly manner, and toward its friends in an inimical manner.

“Today, American behavior and policy are contributing to a very heightened danger of a major conflagration because of how they have done things, for example, the withdrawal from Afghanistan, which I think is nothing short of criminal. We did not need to do that. Mistakes were being made, but I think people don’t realize that there was significant progress being achieved.

“The withdrawal from Afghanistan contributed to a very significant perception of American weakness. And this administration has continued in that direction in almost every way. Even the story with Ukraine has been very poorly managed, not only by this administration but before as well. This is a general problem in American foreign policy, that they start paying attention only when it reaches crisis level, and then it immediately leads to a military option without thinking about the consequences of the military option.”

What could the US have done in advance, especially with Putin, other than rushing troops to Ukraine? What would deter someone like Putin?

“The short answer is, I’m not sure much could, but at the same time, I believe that what these kinds of dictators, or, if you want, the bullies on the international scene do is, they act because they believe they are not going to meet resistance. If they know ahead of time that there will be resistance, and if that image is conveyed forcefully, then I think they will think twice.

“But you must send this kind of signal to the Russians, that this type of war is not legitimate in the 21st century, and you cannot conquer and keep territory this way. The only one who has said that publicly, and these are not the paragons of righteousness, is the Indian government and Prime Minister Modi when he went and met with Putin.

“The US did not have to immediately send troops, but you can start talking and initiating discussions that send a signal. You can bolster American presence in NATO countries. You can insist much more forcefully that the Europeans have to contribute, because they were not even contributing two percent of the defense budget.

“You can also begin to detach and lessen European dependence on Russia for oil and gas. They can diversify and begin to do things that move in that direction.”

Does Zelensky have to negotiate with Putin, or can he say, “Listen, you invaded me, I have nothing to talk to you about”?

“At this point, I would quite agree with Zelensky that he shouldn’t. The problem is that in the West, you have people who are saying, ‘Well, they really should make peace, they should accept ceding some territory to Russia.’

“The ones who understand what is going on are the Finns, the Poles, and the Swedes. Finland and Sweden were neutral. Now they want to be part of NATO. Why? Because they know what’s coming. They know the Russians and their appetite to grab more. Putin has said openly that the greatest catastrophe is the fall of the Soviet Union, and he wants to restore not only the Soviet Union but the Russian Empire.

“So, if you say, ‘Okay, you can have this piece of land,’ and when he attacks, you start giving in, this is what I call the politics of blackmail. It’s a mentality on the part of those who are well-to-do in the West. They say, ‘Let’s pay him a ransom.’ And then it doesn’t end, until it gets to a point where you say, ‘I can’t anymore,’ and you then have to use force to get rid of the threat. By that time, the threat has become so huge that you have massive casualties…. There are no guarantees when you deal with politics or international relations. If you want guarantees you shouldn’t be playing the game. It doesn’t exist. But you have things that over the course of history have proven to work.”

So how do you handle Putin now, since the cat is now out of the bag?

“If there is one thing about Putin, it is that he is very intelligent. Very calculating. And when you have stories published in the press about various people in Russia, for instance, saying that they would launch a war and that they should attack Poland…. One higher official was saying, ‘Well, England is supporting Ukraine and sending them military aid, so we should attack London.’ Those things are not accidental. This is surmising on my part, but it’s not so farfetched — Putin is sending messages, that, ‘If you think I’m bad, look at all those other people who might take over if I’m gone. Do you want to deal with them? If you think I’m a nut, look at the other nuts. They are far worse than I am.’ ”

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 956)

Oops! We could not locate your form.