Keys to the Kingdom

| July 13, 2021This is a story about an old iron key that opened the gate to the Western Wall

It was June 7, 1967, and there they stood, in front of the locked, looming gate — these battle-weary soldiers who suddenly found themselves leading the way to liberating the Kosel. The abandoned Wall loomed up just on the other side of the gate, but although they’d come this far, it was out of reach. They tried to move the heavy iron handle, but the gate wouldn’t give. Should they break through by force?

And suddenly, out of nowhere, there he was — an ancient Arab with a huge key hanging from a rubber string under his robe. “Here, open it,” said the mysterious Arab, who vanished just as suddenly as he had appeared. The key was inserted into the lock. The gate swung open. The way to the Kosel was clear.

By June 6, the second day of the 1967 Six Day War, the Egyptian front in Israel’s south had miraculously capitulated — its air force had been decimated while still on the tarmac, its ground troops fled or captured. And so, the 55th Paratroopers Brigade, which was originally earmarked for the south, was deployed to Jerusalem instead. The official mission was to protect supply convoys headed to Mount Scopus, the only enclave in eastern Jerusalem that Israel still held since the 1948 War of Independence — but there was talk in the High Command and among soldiers about taking the Old City in Jordanian-controlled eastern Jerusalem as well.

That night, soldiers faced excruciating hand-to-hand combat against elite Jordanian troops in the trenches at Ammunition Hill, which overlooked the road to Mount Scopus (today it’s at the end of Levi Eshkol Boulevard abutting the northern edge of Maalot Dafna), but by the next morning, despite Israel’s heavy losses, the paratroopers discovered that most of the Jordanian troops had retreated from Jerusalem. Israel’s cabinet, long divided about whether to capture the Old City, finally gave the go-ahead, and the 55th Brigade was commanded to enter. “We are sitting on the ride overlooking the Old City, and we shall soon enter it — the Old City of Jerusalem, which generations have dreamed of and longed for. We will be the first to enter,” came the charge from famed commander Motta Gur.

The paratroopers rushed forward amid sniper fire from remaining Jordanian legionnaires. They rammed their way through the locked Lions’ Gate on the eastern wall of the Old City, a few tank shells ripping the doors off their hinges, and the paratroopers surged through.

“We stormed into the Muslim Quarter of the Old City through the Via Dolorosa with the commander Yoram Zamosh leading the way,” Rafi Malka, company commander number two, recalls in a conversation with Mishpacha.

It’s been 54 years, but the memories haven’t faded for Malka, who today lives in an assisted living facility with his wife Chana on kibbutz Tel Yitzchak.

“By the time we’d surged through Lions’ Gate, our company had already taken heavy casualties. But the thinking behind the decision was that an advance through Lions’ Gate would be met with relatively light Jordanian resistance, compared to an advance through Jaffa Gate or elsewhere, where resistance was expected to be much stiffer.”

The resistance was, in fact, light, but there was another problem: None of the soldiers had ever been in the Old City before, and navigating the narrow alleyways was a huge challenge in enemy territory. They continued the advance, and when they saw the golden dome of the Mosque of Omar, they knew they were headed in the right direction. Moving past the mosque, the paratroopers found themselves on Har Habayis on the other side of the Kosel and the Mughrabi Quarter — a slum built up to the wall where the Kosel Plaza stands today — when they suddenly saw the high upper layers of the Kosel stones.

“The Jordanians had yet to lay down their arms, but at that moment all we could think of was that we were fulfilling the dream of millions of Jews,” Malka remembers. “We were overwhelmed.”

But they were stuck at the other side of the Mughrabi Gate, the opening to Har Habayis that today is at the top of the ramp to the right of the women’s section at the Kosel — the only entrance for non-Muslims to the Har Habayis. The Mughrabis, who came from North Africa (the Maghreb), settled in Jerusalem hundreds of years ago after fighting in Saladin’s army, creating a neighborhood adjoining the Kosel and Har Habayis. The neighborhood effectively controlled the approach to the Kosel — there were only a few feet between the houses and the Western Wall — and for generations, Jews were forced to pay a bribe to be allowed access to the Wall. The neighborhood, a veritable shantytown of hovels and filth, was poor, shabby, and squalid, with its public toilets abutting the Kosel.

“It was so close to us,” says Malka, “but when we found the gate, it was locked. We stood there, gazing at the top of the Kosel — so close but so far. But we weren’t going to blow the hinges off this time or smash through the gate with a tank. Here, you don’t blow anything up. When you see the Kosel stones looming above you, you put away your grenades. And at this point there was no longer any resistance. But still, what were we going to do next?

“And then he appeared out of nowhere, this elderly Arab in a white jalabiyeh, coming toward us. The company commander, Yoram Zamosh, ordered me to address him in Arabic. I asked him how we could get down to the Kosel.

“His answer shocked me,” Malka continues. “He said, ‘I’ve been waiting for you 19 years. I knew you would come. This is the key to the Mughrabi Gate. I came to show you the way.’

“At the time, we were all shocked, but later, we figured that he might have been the gatekeeper of the Muslim Waqf — or maybe, some of the soldiers said, he was an apparition? As he spoke, from around his neck he removed a string, to which was attached a key about 30 centimeters long, and he handed it to me.

“Zev Parnas, another paratrooper, inserted the key into the lock and turned it clockwise once or twice. The gate swung open. We all broke into a run. As we ran down the ramp to the narrow alleyway in front of the Kotel, still under threat of sniper fire, my heart skipped a few beats. Was this really happening? Were we really about to see the Kotel again?”

As the troops approached, commander Yoram Zamosh whispered, “Kotel, Kotel, we’ve returned.” He was overwhelmed by the historic reunion with the holy site. He had only seen it once before, as a small child, but had now merited to be one of the chosen few who liberated the site from the Jordanian enemy. Zamosh had the honor of pitching the Israeli flag on the holy stones. Zamosh later went on to learn at Yeshivat Mercaz Harav and until today is an activist for the historical integrity of Jerusalem.

Another soldier, Avraham Shechter, leaned on the stone wall, wept uncontrollably and laid tefillin. Yossi Offner also took out his tefillin and put them on. Moshe Stempel, the deputy brigade commander, couldn’t restrain his emotion. His face was bathed in tears as he told his commander, “Zamosh, we aren’t settling accounts with the Jordanian legionnaires today. We’re settling accounts with the Roman legionnaires of Titus.”

Rafi Malka would later write: “For all the excitement washing over me, I’m not sure that at that moment I was really capable of grasping the full significance of what was happening. It seems to me that even those of us who were religious couldn’t take in the full meaning and power of the moment.”

Later, when Malka was told that he’d been the first paratrooper to touch the Kosel, he had no recollection of it. It all happened so fast and was so overwhelming.

Locked Out

“After we went down to the Kotel and all rejoiced and prayed, the company continued on to Kishleh and Jaffa Gate, in order to secure the liberation of the Old City,” Zev Parnas tells Mishpacha. “Rafi Malka, who was second in command, ordered me to stay at the Kotel and supervise eight or nine other soldiers who were left behind to keep watch on the Arab families from the Mughrabi Quarter. In addition, I was responsible for security for the rabbanim and others figures who started streaming to the Kotel as soon as word got out. So I guess you could say I was the ‘first commander’ of the Kotel.”

On the night of June 10, Israel evacuated the residents of the Mughrabi neighborhood and demolished the buildings. The families were compensated and received assistance in finding new homes.

And the key? Who has it today?

“I handed it to Zev Parnas, and since he opened the door and the Arab disappeared, I told him to keep it,” says Rafi Malka, “until it was eventually transferred to the Ammunition Hill national memorial site.”

“That Arab appeared out of nowhere, as if out of the mists of time,” Parnas adds. “And we never saw him again. But he was very old, and we were basically kids. I kept the key, but later, when they started collecting artifacts for historical documentation, I brought it in to supplement the collection.”

Two years ago, the Kosel “liberators” had a reunion at the site of the battle, and the director of the Ammunition Hill memorial site brought the key with him, asked who had been the one to actually open the gate, and when he found Parnas, he put the key around the veteran’s neck.”

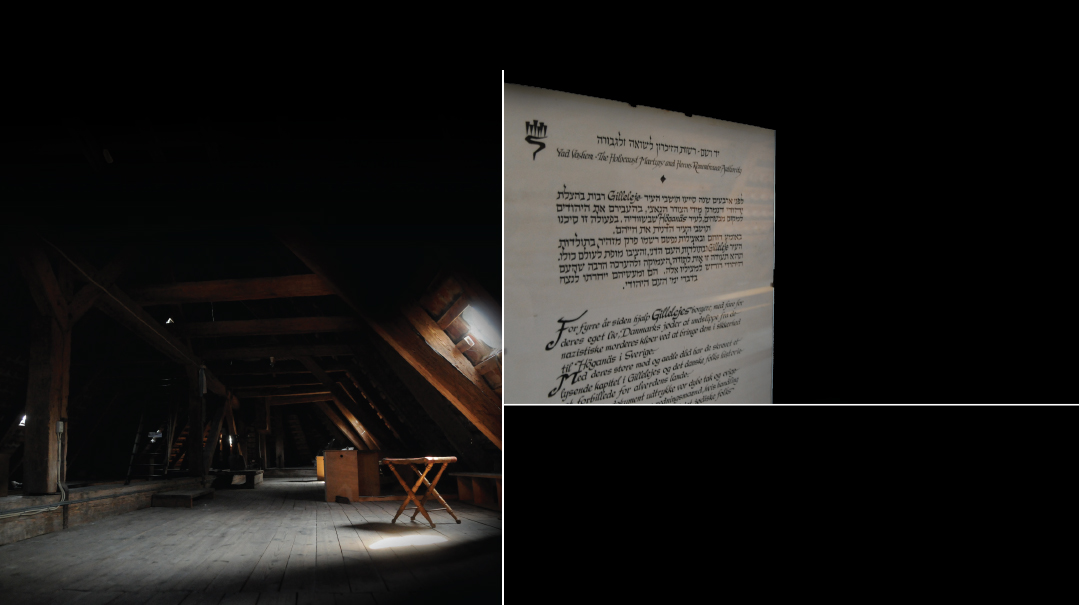

“Today the key is with us, in a safe, at Ammunition Hill,” says Alon Wald, director of the memorial site and son of Rami Wald Hy”d, killed in the battle over Ammunition Hill.

No inspiring story can escape some politics on the side as well. The soldiers of the Jerusalem Brigade, which blocked a Jordanian offensive in the south of the city and captured the area of Armon Hanatizv, have always claimed that they were the first to arrive at the Kosel. According to them, the 55th Paratrooper Brigade and its commanders stole the credit.

That’s because at pretty much the same time, the Jerusalem Brigade penetrated into the Old City through the southern Dung Gate. According to their account, they wanted to push on straight to the Kosel but were purposely held back until the paratroopers arrived, and some of their troops indeed arrived first, before the paratroopers (because they didn’t approach the Kosel from above, they avoided the halachic violation of ascending Har Habayis).

But whether the key was necessary to open the gate or not, it’s still become a cause of lasting Arab resentment.

In February 1985, the monitoring committee for the preservation of the status quo on the Temple Mount, the leadership of which is shared by the National Council of Arab Mayors and Arab Knesset members, called for then-police minister Haim Bar Lev to hand the keys to Mughrabi Gate back to the Waqf. (Despite the liberation of Jerusalem in 1967, then-defense minister Moshe Dayan’s first act on Har Habayis, only a few hours after IDF Chief Rabbi Shlomo Goren blew the shofar and made the shehecheyanu brachah beside the Western Wall, was to immediately remove the Israeli flag that the paratroopers had raised on the mount and restore all internal authority of the Mount to the Muslim Waqf, which they maintain until today.)

Prior to August 1967, tourists who went up to Har Habayis via the Mughrabi Gate (the only entrance for non-Muslims) paid an entrance fee. Israel opposed this, and the keys to the Mughrabi Gate were taken from the Waqf — the only Temple Mount gate whose keys are in possession of the State of Israel.

In 2015, almost 50 years after the war, the Jerusalem mufti Achrama Sabri called on the Israeli government to restore the keys leading to the Temple Mount to the Muslims: “The Muslim people must demand the keys of the Mughrabi Gate of Al-Aqsa, in order to evict the occupier who seized it illegally in 1967, and still has discretion over the opening and closing of the gate.”

The demand to return the key resonated as far as Ankara. Turkey has long directed efforts to stir up Muslim sentiments in the Middle East, which includes financing Arab NGOs active in East Jerusalem. The Turkish NGO Burj al-Laqlaq created a computer game called “Guardian of Al-Aqsa,” where players try to reach the Al-Aqsa Mosque by winning the key to the Mughrabi Gate.

Heaven’s Latch

The key that opened the way to the Kosel might be merely a symbolic artifact, but its roots go back to our tradition in relation to churban and geulah.

Chazal relate that at the time of the churban of the first Beis Hamikdash, the young Kohanim assembled with the keys of the Heichal. When they saw the Heichal going up in flames, they climbed on the roof and said: “Ribbono Shel Olam, since we weren’t worthy to remain Your stewards, let the keys return to Your keeping.”

And the Gemara recounts that when they threw the keys upward, a Hand reached out from Shamayim and caught them. The Kohanim then perished in the flames and ascended to Shamayim in purity together with the Beis Hamikdash.

Nearly 2,500 years later, the Jews were back and in need of a key. If it wasn’t the key to the Beis Hamikdash, at least it was a key to its last remnant, the wall of wails and prayers from which the Shechinah never departs.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 869)

Oops! We could not locate your form.