Just Like His Children

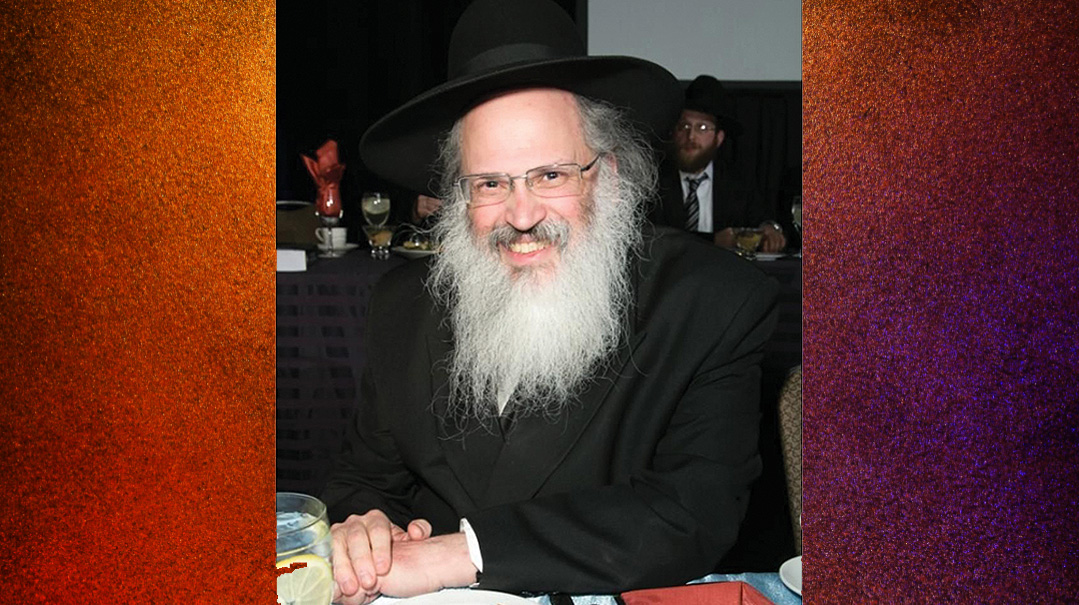

In memory of Rav Shmuel Yehuda Levin

IT was this past Motzaei Shabbos, as Klal Yisrael prepared for the fast of Shivah Asar B’Tammuz, when the bochurim of Telshe Chicago were urgently instructed to gather in the beis medrash to recite Tehillim. The rosh yeshivah, Rav Shmuel Yehuda Levin, who just hours earlier had delivered a shmuess in the yeshivah, had suffered a massive heart attack, his condition critical. But then the shocking news came, and the fervent prayers transformed into a wave of grief and anguish. Rav Shmuel Yehuda Levin, pillar of fiery brilliance and steadfast devotion who was crowned rosh yeshivah of Telshe Chicago less than four years ago with the petirah of his father, Rav Avraham Chaim Levin, was gone in a flash — leaving the Chicago community, along with the whole olam hayeshivos, reeling.

Until his father’s passing, Rav Shmuel served as the yeshivah’s first-year maggid shiur, in addition to giving multiple other shiurim and chaburos to various age groups throughout the yeshivah. When his father was niftar, he assumed the mantle of leadership, and began delivering the yeshivah’s highest shiur.

But not only. “When he initially became rosh yeshivah,” one talmid recalls, “he would give two shiurim daily. He continued to give the shiur to the first-year bochurim, and then gave a second shiur to the older bochurim. He did this until the final arrangements for a new maggid shiur were in place.”

This setup was extremely difficult for Rav Shmuel, whose schedule was amply taxing as it was; he was also well aware that the convenient thing to do would be to combine the two shiurim together for the time being. But he wouldn’t. He felt that a shiur must be tailored to the students’ level — not any higher, not any lower.

This doesn’t really surprise anyone who knew him. That he treated each talmid like his own child is a theme that was raised multiple times during the hespedim, and it was a reality that his talmidim could tangibly feel.

“He would often tell us that his house was an extension of the yeshivah,” a talmid reflects. “We would go to his home to speak in learning until midnight, sometimes well beyond.”

On Yamim Tovim, when his house was already teeming with children and grandchildren, he would rejoice at the visit of every talmid and former talmid, and if the talmid brought his children along, all the more so. It wasn’t a burden — they were family as well and were welcomed with equal joy.

The talmidim knew it, but a speech Rav Shmuel delivered at the recent Torah Umesorah convention made it clear to the rest of the world.

“What is the definition of a good rebbi?” he asked the audience. “In birchos haTorah we daven for tze’etza’einu, our children — and tze’etza’ei amcha beis Yisrael, the children of Bnei Yisrael… A good rebbi is one who thinks of his talmidim when saying the word tze’etza’einu, as opposed to tze’etza’ei amcha beis Yisrael.”

Rav Shmuel saw this not merely as a personal methodology, but as the very backbone of the transferring of Torah to the next generation. His son, Rav Efraim Mordechai, related that his father would quote the Gemara in Berachos (61b) that discusses the unfathomably tragic death of Rabi Akiva. As Roman henchmen tore his skin with combs of steel, Rabi Akiva cried the eternal mantra of “Shema Yisrael!” to which his talmidim asked,“Rabbeinu ad kan — Rebbi, must you go this far?!” Rabi Akiva turned to them and responded that the Torah says, “B’chol nafshecha — we must serve Hashem with our entire soul, up until the very last moment.”

Rav Shmuel saw a profound message hidden within this dialogue. Rabi Akiva was breathing his final breath, his soul clearly bound to a world beyond pain and suffering. Yet he took these last crucial moments to answer a talmid’s question. It was the lasting legacy of Rabi Akiva, one of the greatest teachers of all time. A talmid’s question needs to be answered. At any time.

But Rabi Akiva’s parting message was one that defined Rav Shmuel in more ways than one. “B’chol nafshecha,” to serve Hashem with utmost completeness. Rav Shmuel would push himself to the limits, tending to his endless responsibilities, creating time where there simply wasn’t any.

A talmid once had an urgent matter and asked Rav Shmuel if he could speak to him. Rav Shmuel thought and sighed.

“I’m sorry,” he said, “my schedule is just too packed today.”

“But Rebbi,” the boy said desperately, “I really need to speak to you.”

Rav Shmuel thought again. “Okay,” he said, “meet me at my home tonight at ten thirty.”

“I showed up at his house at ten thirty,” the talmid recalls, “and we spoke as if he had all the time in the world.”

Rav Shmuel himself once hinted at the secret of his method. He once appointed a talmid to transcribe the shiur and present it to him for future reference. At some point, the talmid approached him.

“Rebbi,” he said, “I would really like to be able to write my own chiddushim, but I can’t, given that my time is taken writing over the shiur.”

Rav Shmuel smiled but did not accede to the request. “I give you a brachah that you should have 28 hours in a day,” he said. “Do both. Write over the shiur and write your own Torah. Find the time for both.”

Rav Shmuel was rosh yeshivah, loving husband, father, grandfather, rebbi, and highly sought-after community leader, and through it all, a tremendous masmid. He somehow found the time for both.

Rav Shmuel’s demanding standards for his talmidim was also a prevalent theme in the yeshivah’s. He believed that, until they reached a certain age, bochurim shouldn’t deliver their own chaburos. He felt that they had not yet matured in learning, and sharing Torah that wasn’t necessarily accurate in a public setting could be harmful. Still, if a boy wanted to say a chaburah, he wouldn’t stifle that desire. The chaburah was said, with Rav Shmuel present.

“He would sit looking very relaxed,” one talmid recalls, “and we all felt it was so that we shouldn’t feel intimidated. But if you said something that he felt wasn’t right, he would call you out on it.”

He had high expectations that he communicated clearly. But his talmidim never saw that as threatening. On the contrary.

“It was all part of his way of seeing us as his children,” a talmid describes. “A father wants his children to succeed, and he might be strict in exacting that result, but it’s all part of his love for his child.”

Like a father, Rav Shmuel was constantly davening for his talmidim. They knew this, and felt perfectly comfortable telling him of a family member who might also be in need of his tefillos. He would daven for them as well, and follow up with the talmid to learn how this relative was faring.

On Shabbos, hours before his petirah, Telshe menahel Rav Moshe Schmeltzer asked Rav Shmuel if he would be saying the shmuess at Shalosh Seudos. Rav Shmuel looked at him strangely and whispered, “I’ll try.” He was perfectly healthy in a physical sense, but the man who lived “b’chol nafshecha” must have perceived that something of the spirit was slipping away.

He did speak. He spoke about the severity of Middas Hadin.

“Mir daft trachten vegen dem, we must think about it,” he emphasized. “We must be cognizant of what Middas Hadin means, how we must relate to it.” Then he concluded. “But in the end, Middas Hadin brings about gutte zachen, it brings yeshuos, it brings an increase in limud Torah, it brings more kevod Shamayim.”

Uncharacteristically, he cried throughout the shmuess. That night, he was niftar, at the prime of his life, a Luchos so brilliant and pristine, shattered, with scores of talmidim grappling to cope with the loss of a father more than rebbi.

Shivah Asar B’Tammuz, when the Luchos shattered, when the wall that fortified Yerushalayim was broken, when the Korban Tamid, the avodah that happened every day uninterrupted, suddenly stopped short.

On 17 Tammuz, Rav Shmuel Levin also left us. But like the Luchos, although they were broken, they continue to remain with us. “Shivrei luchos munachin b’aron — the broken Luchos too were placed in the Aron Hakodesh, traveling along with Bnei Yisrael wherever they went.

And so, too, Rav Shmuel Yehuda Levin remains with his yeshivah, the same rebbi, the same father, that he always was. He may not be seen but he’ll be felt, present as ever before, his magnificent heart, his magnificent soul, “b’chol levavo, ub’chol nafsho.”

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 920)

Oops! We could not locate your form.