Just Answer “No” — The Conversation Continues

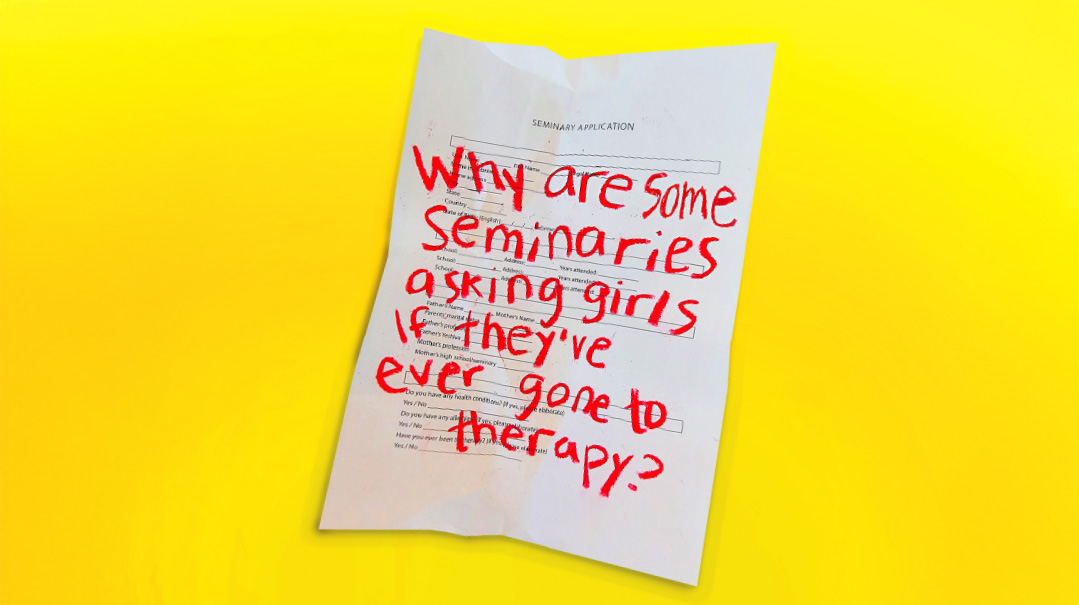

Should seminaries ask applicants if they’ve gone to therapy?

Rabbi Yaakov Bender

rosh yeshivah of Yeshiva Darchei Torah

“Two and a half years ago, when I first saw this phenomenon, I wrote a very strong letter to the seminaries that asked about therapy and medication on their applications. Two seminaries did remove the question from their applications. The others kept it on there.

We don’t push therapy on children. We encourage it when it’s necessary, but how can we tell these girls that they won’t get into seminary because of it? The seminaries say that they don’t care about the answer — but then, why are they asking the question? No seminary is asking questions that don’t matter to them.

I work closely with Links, the organization founded by Mrs. Kohn to support children who’ve lost a parent, and often we recommend a girl work through this loss in therapy. Yet most of the time, if a girl writes that she’s in therapy on her application, the application will immediately be discarded.

If the seminary wants to ask about therapy or medication after they’ve accepted a girl, because they want to know how to best prepare for her, then it might be a valid question.

But seminaries are asking it beforehand to weed those girls out. We shouldn’t turn away a girl who needs therapy or medication. If a girl has a serious psychiatric issue, she probably shouldn’t be sent to Eretz Yisrael in the first place. But if she takes some anti-anxiety medication, should that be a reason to reject her? It’s destroying these girls. And regardless of what seminaries might say, the reality that I see, again and again, is that the seminaries are hurting girls over this.

Like many rabbanim, I am asked to advise girls whether or not to answer the question with full accuracy on their applications. What I tell them is private, but I can tell you that the seminaries would not be happy about it. I also know that if the girls don’t answer in that way, they’ll never get into a seminary at all.”

Rabbi Zev Katz

menahel of Yeshiva of Greater Washington

I’d like to express my thanks and admiration to Mrs. Kohn for bringing this issue to the fore. As menahel of a girls’ high school for over 40 years, this topic has percolated in my mind for decades, and I eagerly wait to hear the perspectives from all sides. I generally try to mind my business and stay out of the fray, but I feel compelled to add my two cents, although it may not be worth that much, unless it’s adjusted for inflation.

I’d like to share a story. Over 25 years ago, when it was rare for people to discuss mental health openly, I was troubled when I first saw this question on a seminary application. One of my students came to me and asked, “Rabbi Katz, how should I answer this? I’m afraid if I tell the truth I’m not going to be accepted, but I don’t really want to lie.”

“I understand your dilemma,” I told her, “but you may not lie. Leave the question blank, and I’ll talk to the seminary and explain your reality.” As the menahel, seminaries always consult with me about applicants, and I’d had every intention to bring up the issue with the seminary. I knew that by leaving it blank, they would surely ask me about this girl — as they did. I told them about the help she received, the circumstances surrounding it, and how it was a past issue that had been dealt with l’mehadrin. The seminary accepted her, she went, and today she has a beautiful mishpachah.

The next year I instructed our talmidos to leave the question blank, explaining why I didn’t think a blanket, broad question was appropriate and that I would discuss any relevant issues with the seminary. This is what I have told them every subsequent year. (And as I warn the seniors many times, girls shouldn’t think they’re just going to write no because they don’t want to make a fuss or because they haven’t even been to therapy — by now, seminaries know of my directive, and my students who disregarded my instructions have been called out during their interviews and asked, “Why did you write that you’ve never gone to therapy if your menahel told you not to answer that question?”)

I’m bothered by the situation. I feel the matter is very individual and nuanced, and that the question is intrusive on every level. I also see its very real fallout: Some girls are given needless scrutiny or even rejected based on their answer, when the therapy related to an issue that was long resolved or irrelevant. Other girls are loath to go for necessary help (particularly in 11th and 12th grade, as the anxiety of leaving home becomes a reality), worried about how it would affect their seminary applications. I’m concerned about stigmatizing mental health. All of this makes me uneasy.

I do understand why seminaries feel compelled to ask. When a school is accepting students, especially in a yearlong boarding situation, this information is vitally important. How can someone withhold information that is probably critical to ensuring that students have a safe, healthy, and productive year?

It’s vital that a school’s seminary advisor or principals share any relevant issues or concerns about potential students with seminaries. I’ve found that being honest about students’ backgrounds allows the seminary to honestly determine if they can handle the issue and prepare for it accordingly. I’m sure that many seminary heads feel that they have legitimate tainehs and feel they have been misled by high school administrations. It’s sad that this is the situation.

But asking this on a form creates a stigma and angst that is frightening. Imagine having a conversation with a wonderful girl that goes like this: “Rabbi Katz, I’m such a different person now that I received the help I needed. Does that make me less of a bas Yisrael than the others?” It’s heartbreaking. A girl who went to therapy is a hero for all the work she put in overcoming circumstances that would have broken many of the adults judging her. Do we want her feeling that the payoff for her self-work is being on what they perceive as the “B-roll?”

I called a universally recognized gadol b’Yisrael and relayed my angst. “What gives them reshus to even ask that question on a written application?” he replied.

“Rebbe, one of the seminary menahalim is going to be at a wedding in Baltimore tonight,” I said. “I know that the Rosh Yeshivah is the mesader kiddushin, and I will be in attendance as well. Perhaps the Rosh Yeshivah could speak with the menahel.” The Rosh Yeshivah said that we could speak to him together, and asked me to bring the application for that mosad with me.

When the Rosh Yeshivah asked why the question was on the application and instead isn’t asked directly to the school representative, the menahel replied that it was because there are very few school representatives that tell the whole truth. Nevertheless, the Rosh Yeshivah directed the menahel to remove the question from their applications (which the school later did).

The Rosh Yeshivah was very clear that the seminary has an achrayus to get the truth by doing due diligence on the students, and the high schools have an even bigger achrayus to tell the truth, otherwise it’s an inyan of lifnei iver and lo saamod al dam reiecha, in addition to sheker.

Really, do we want girls walking into this process feeling they have no chance to get into their top choice of seminary if they are honest? Do we really want them to believe that walking out of high school and onto the next stage of life requires them to fiddle with the truth?

I don’t profess to have the answers, but that doesn’t mean we should shy away from the conversations and questions, especially this one. It would seem to me that if we had a real truthful conversation about this question — about the concerns, about the issues, about the goals — we would find our way through this.

After 25 years, I think we would all agree it’s about time.

Rabbi Zecharya Greenwald

dean of Meohr Bais Yaakov

Mrs. Kohn opened with a question: Why are some seminaries asking girls if they’ve ever gone to therapy?

The article quoted a high school teacher who says she “understands” where the seminaries are coming from. “They’re overwhelmed with caring for so many girls 24/7 for months on end,” the teacher says. “They’re looking to have the most low-maintenance girls possible. Because they always will have challenges.”

I don’t think this teacher truly understands the seminaries’ mindset. While it can be overwhelming to deal with mental health issues in a dormitory setting, this doesn’t mean seminaries are looking for low-maintenance girls. It means they’re filtering out students they can’t properly support.

Another teacher is quoted as saying, “If a girl says she’s in therapy for anxiety or depression or OCD, on the other hand, the seminary may feel it’s above their pay grade. So those are the ones I advise to just say no [in answer to the question on the application form].”

It actually sounds like gross negligence to tell a girl with challenges above the school’s pay grade to lie in order to get in there. How can this teacher believe she’s doing a girl a favor by facilitating her acceptance into a school that lacks the tools to help her?

There are many levels of mental health challenges. Does a high school teacher understand the dynamics of a dorm room with a girl suffering from intense OCD? Does anyone who doesn’t run a full-time dormitory understand the effect of a girl suffering from severe depression or anxiety on the other girls in her room, apartment, or class?

Mrs. Kohn tells of a recent convention that had no less than three major sessions on therapy-related topics presented by clinicians alongside rabbanim. “We’re creating a climate in which we begin normalizing getting help instead of helpless hand-wringing,” she wrote. She’s working to create a situation where just like, “there’s no stigma around an ear infection, there should be no stigma around mental health conditions either.”

All of this is true. And the point is not stigma, but health. Would you send a girl to seminary without informing them that she had epilepsy or diabetes or Crohn’s? They aren’t generally life-threatening and need not be overly disruptive, but they require that all medical protocols are in place, that the student can get adequate sleep, and that her dietary needs can be provided.

Does a school not have the right and responsibility to assess their readiness to deal with these illnesses? Do they have the staff, support staff, in-house kitchen or catering? Again, forget “stigma.” We’re talking about a girl’s life and her future.

Mental health can be reasonable to deal with or it can be disruptive to an entire school population. When a girl has a breakdown or attack it has repercussions on everyone around her.

Mrs. Kohn writes of high school teachers assisting in the seminary acceptance process, “None would go on the record. ‘I’ll lose the trust of the seminaries for the advice I have to give my students,’ was the line I kept hearing.”

The teachers need to know: Yes, you would lose your credibility if we know that you are hiding important information. 50 girls a year get sent home from a range of schools causing pain, distress, and sometimes, long-term challenges. How many of those situations could have been avoided?

For the record, I took that question off our application after learning that it just created another “opportunity” for lying. Instead, the application asks, “Have you taken medication for a period of one month or more in the past three years?”

Falsification of that information is grounds for sending a girl home should we discover it.

Do these high school advisors think seminaries should blindly take responsibility for a medical or mental health situation of which they are not aware?

Applying to seminary is one of the first times teenagers have to be real and honest about who they are and what they want.

Excuse me for being forward, but seminary is not for everyone, and it’s sad that we have to be the villains who tell a girl that she should not be coming, even though her friends are. High schools and parents should take a bit more responsibility. Parents, educators, and clinicians should be having more dialogue with the seminaries. Then perhaps a small piece of this painful process can be more humane.

Do You Take Tylenol?

Mrs. Shevi Samet

I was grateful to see Sarah Rivkah Kohn’s article addressing a prevalent issue with many fallouts. As a high school mechaneches who guides her students through this process and interfaces with seminaries, it’s a reality I am intimately familiar with. While there are many facets to this problem, including the chinuch ramifications when dishonesty is encouraged and the impact this question has on whether a student will seek out the help they need, I believe that there is an additional point worth mentioning. The seminaries rightfully assert that they cannot support a girl if they don’t know what she needs, however the question, “Are you in therapy?” doesn’t actually tell them anything useful! In the majority of cases, therapy is the solution and the question alone doesn’t articulate what problem it may or may not be addressing. Asking if a student is in therapy is like asking if they take Tylenol. It may be a headache or a toothache or something else entirely; asking how you address a problem doesn’t tell you anything about what the problem is or whether you have developed the skills and resilience necessary to navigate an environment like seminary. One may presume to infer something useful from the question but in fact, it is attacking the solution and driving the problem underground, further exacerbating the legitimate challenge seminaries face which is, “How can we ensure that the growth experience seminary can facilitate is not undermined by the inherent vulnerability it creates for some students?”

Do We Have the Resources?

Mrs. Batya Weinberg

Sarah Rivkah Kohn should be blessed. She has done tremendous work removing social blocks and normalizing mental health intervention. However, to suggest that seminaries are reversing this trend is perplexing at best.

Seminaries are far from therapy- or medication-averse. It’s not uncommon for young women in Eretz Yisrael to start either or both with the encouragement and guidance of her seminary.

It’s with an assumption of a mature, open attitude toward mental health that seminaries ask about an applicant’s history on a medical questionnaire or application. The questions are formulated differently for every school. Some ask about therapy; others aren’t comfortable with that, but ask about specific mental health disorders, and about medication. This isn’t limited to Bais Yaakovs, as can be seen from the medical form on the “Joint Sem Application” sent out cooperatively by 20 non-Bais Yaakov seminaries.

The purpose is the same: It’s not to block anyone, but to responsibly see if a seminary has the resources to support said student. Usually, if she is a good fit, she will be accepted pending medical clearance. Perhaps her therapist or nutritionist will also be asked to coordinate with the school prior to her arrival to ensure that she can be supported through the multiple stressors she’s likely to encounter.

The experienced, wise, kind principals I know do not accept or reject students with a simplistic, “Nu, are you in therapy: yes or no?” They don’t categorize anyone that way, and certainly not their present or potential talmidos. They are also astute and will often know when they are being hoodwinked. The head of one of the most prestigious Bais Yaakov seminaries in Yerushalayim said clearly, “Upright, up-front parents are the ones we want.”

A seminary may decide that they can’t properly absorb whatever issue it is, and they have every right and responsibility to decide where to allocate their energies and what risks to take. It might come down to an assessment of emotional resilience, being fair to roommates and other students, or basic safety.

Other times, and I heard this from quite a number of principals, a girl will davka be accepted because of how much she has built herself and her readiness to deal with her challenges.

Seminaries have to deal with each situation on a case-by-case basis. If this understandable reality causes people to revert back to outdated approaches and hide their history, this isn’t the fault of the seminaries, but of whoever is falsely filling out those forms, or those advising them. Hiding crucial information is not only unfair, but extremely dangerous.

Untreated is Worse

A.M.

I was quite intrigued when I read this article, and it sent a lot of thoughts going through my mind. I was just in seminary this past year, and am quite familiar with the dorm setting: One hundred teenage girls together on their own 24/7 (not sure whose brilliant idea that was). I’ve personally gone to therapy and taken medicine since a young age and have used it to grow and to improve my life. On a day-to-day basis, I function completely normally. When it came to filling out my seminary application, I asked my seminary advisor what to write. She told me that she can’t answer this question, and that I must ask daas Torah. I consulted with a rav, and the psak I was given was not to write that I’d gone to therapy. Obviously, when I would fill out my medical forms for seminary upon acceptance, they would know of my medications.

Upon arriving in seminary, I met a girl who went through extreme traumas, suffering, and abuse that no one should ever have to know of. Due to many reasons beyond her control, she never received proper therapy or help. She wasn’t a stable person capable of making healthy relationships. Living in the environment of seminary without any proper support made things worse. She needed the type of support a seminary isn’t capable of supplying. Her application would have said that she never went to therapy or took any medication. This doesn’t say anything about her mental health status. She made things very difficult for many other girls in seminary, due to her inability to form healthy relationships.

I very much understand that every girl wants to go to seminary. When thinking about applying to seminary, you should ask yourself if your mental health is stable enough for the intense and rigorous environment. Not getting proper support can hurt many others, but it will hurt you the most. You will not be able to reap the spiritual benefits of seminary and Eretz Yisrael if you’re not mentally and emotionally stable. You need to work out all your mental health problems before you go to seminary because the seminary environment will exacerbate the issues. It may not be worth going to seminary if the risk is that you will hurt yourself and many others severely.

On a side note, if you find yourself in a situation where the seminary experience brings previously unnoticed issues to the surface, know that you are 100 percent normal and that it’s important to reach out for support and do whatever you need to do to prevent issues from spiraling out of control. This may not be the growth you expected to do in seminary, but it’s most definitely worth it and will help you become a better person.

Once They’re Accepted

Naomi Franklin, LCSW-R, Monsey and Swan Lake, New York

I totally agree with Sarah Rivkah Kohn that it would be very sad to go back to stigmatizing mental health treatment. In my experience, going to therapy is a sign of maturity and indicates that the girl, and most often her parents, are trying to get help for whatever is needed.

At the same time, having been on the other side as an administrator and camp mother, I can certainly understand the seminaries not wanting to take on more than they can handle, or potentially hurting other girls or negatively impacting their experiences. I’m assuming that these questions started showing up on the applications after awful experiences.

When people didn’t tell the truth — say, the parents of a boy with ADHD didn’t tell us their son needed to take medication — the results were disastrous and unfortunate. And when principals and teachers lied to us about the functional level of our campers, we had a couple of horrific experiences as well. I can also think of someone whose teenage child was traumatized when a suicidal peer (not in therapy) shared with their child about their suicidal ideation. Many issues that teens might go to therapy for are not so severe and would not grossly affect their functioning.

One colleague of mine suggested that seminaries not ask these questions on the initial applications, but only ask them once the applicant is accepted. I understand it would create more work for the seminaries, which would be difficult to have a two-step process whereby they accept girls conditionally, get the sensitive information that they keep confidential, and then let a few unfortunate applicants know that unfortunately, they won’t be able to accommodate them.

But to have such sensitive information on a standard application doesn’t seem appropriate. There should be some way that seminaries can get the information they need so they can decide if they can handle this, or make sure that therapy is in place to support a girl in Israel or out of town. We want to enable the girls to have a good, safe, healthy experience, as well as make sure we’re not rejecting a girl with mild emotional issues or stable mental health issues.

These Girls Are Assets

Chaviva Friedman, Los Angeles, CA

This article hit a nerve. My husband a”h died suddenly while my daughter was in sem. One perk of being in the “dead daddy club” is she could now go to therapy without the community labeling her as damaged goods. But I remember when she was applying to seminary and that question came up. She hadn’t considered therapy at that time, but for me the question was so triggering because I truly don’t believe that question is so they can best support our daughters. That question is to screen those girls out. Look at the girl and her behavior, not her private health care information. Let’s stop labeling girls as good or bad, quality or not. Let’s stop saying constantly, “The makeup of the girls is so important, it makes or breaks the seminary year.” No. It’s the quality of the seminary that does that.

It’s not easy to access and pay for mental health services in the United States, even with good insurance. If a young lady and her family feel it is necessary and are persistent enough to make it happen, and the girl follows through and goes, that is a powerful woman in the making who would be an asset to any seminary.

It’s to Weed Us Out

Name Withheld

I applied to seminary three years ago. Two out of three seminaries I applied to asked not just if I was in therapy, but if I had ever been.

I asked a sh’eilah about what to answer because my mother was pretty sure they wouldn’t accept me if I had gone to therapy.

My rav said I could leave the question blank or I could answer yes, but I shouldn’t lie. He also offered that I could put his name and number as a reference for any therapy-related questions.

One of the seminaries called him and accepted me. The other one never called, and rejected me. I have no idea if the fact I went to therapy was the reason for my rejection, but I had a wonderful year in a place that was understanding and respectful.

I don’t think many of us who went to therapy have a problem answering the question. I think many of us feel that the question is there as a means of filtering us out, and that’s the problem.

(Originally featured in Family First, Issue 924)

Oops! We could not locate your form.