Jump for Your Life

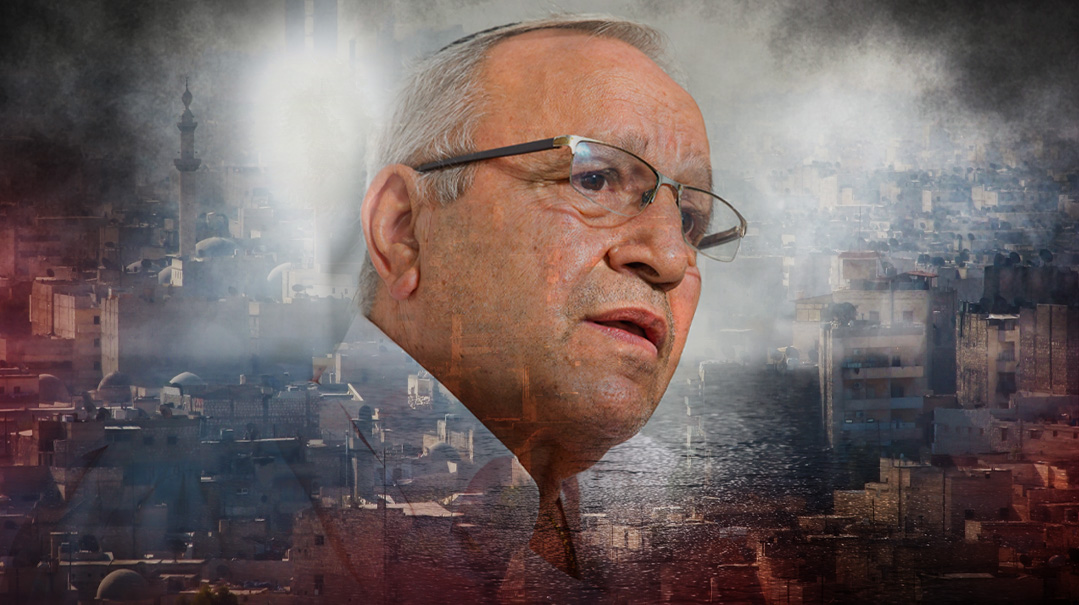

| May 24, 2022Six decades later, Shlomo Malach is still thanking Hashem for the miracle of surviving

Photos: Elchanan Kotler, Family archives

The order that came from the command center of the Italian passenger ship didn’t leave room for an argument: “Get rid of the boy as quickly as possible!”

At sea, that means only one thing: Throw the young fellow overboard.

It was 1962, and Shlomo Malach, a 13-year-old Jewish boy from Damascus, had crossed the border to Lebanon and stolen onto the ship at the port of Beirut. The security agents who were commanded to carry out the brutal order requested backup.

A dozen sailor hands found Shlomo in a tiny steerage cabin, grabbed him, and dragged him onto the deck. He was a fast and wiry little guy and at first managed to escape their grasp, zigzagging all over the large ship in order to avoid becoming fish food.

But it was a hopeless battle — and just a matter of time until the posse caught up with him. He reconciled with his fate of being tossed overboard, his mind empty except for one painful thought: After everything he’d been through, his mission had not been accomplished.

Just before he was hurled amid the waves, he had an opportunity for a last request. “Give me a life preserver,” he begged. “I prefer to throw myself into the water.” No one objected. In the middle of the Mediterranean Sea, it really made no difference if you had a life preserver or not...

Every Shavuos, Syrian-born Shlomo Malach celebrates an anniversary, and this year will be no different: not a birthday exactly, but maybe a kind of rebirth. It was right before Shavuos of 1963 that then-13-year-old Shlomo Malach finally managed to cross the border between Syria and Lebanon after several attempts, sending him on a years-long odyssey of peril and torture. He was determined to get to Eretz Yisrael — so close, really, just over 60 miles — but his harrowing, heart-stopping journey traversed several years and continents with open miracles that kept death in abeyance.

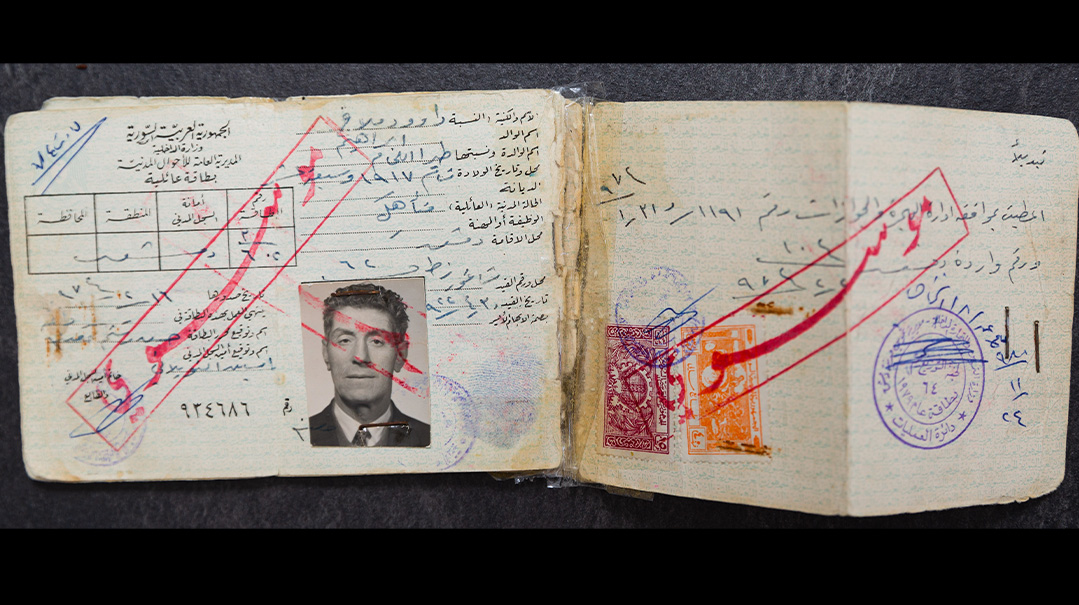

Shlomo Malach was born in Damascus, Syria, in October of 1949, the fourth of nine children. It was a year after the establishment of the State of Israel, which meant a difficult and dangerous period for the Jews of Arab nations in general, and of Syria in particular. In Damascus, Jews weren’t allowed to travel more than ten kilometers from their place of residence, and their ID cards were stamped with the word “Jew” in a bright red ink. The Jewish state that had been established to the south had turned the locals into spies and traitors. Arabs who had fled from the war to Syria disseminated hate and fear, which began to rage in the Jewish quarter. The Mukhabarat — the secret police — patrolled the streets hunting for “traitors.”

No one was allowed to talk about the fledgling state, but Shlomo dreamed about the Holy Land. And soon after his bar mitzvah, his childish thoughts about making his way to Israel gave way to more realistic plans, as he tried to practically work out an escape.

“I didn’t share my thoughts with anyone, not even my family,” he tells Mishpacha decades later. “The rumors of Jews who were caught smuggling across the border were horrible. They were brutally tortured and then returned to their homes after losing their sanity. And we all knew about four sisters, relatives of ours, who were slaughtered trying to cross the border. So there was no way I could share my plan with anyone.”

One day toward evening, Shlomo slipped out of his parents’ home and made his way to the train, taking nothing but a few currency notes to help him along the way. The train took him to the town of Zabadani, the last stop near the border. The station was outside the town, and under the cover of darkness, Shlomo slipped away unnoticed.

He decided to walk along the rail tracks, thinking that he’d reach Lebanon that way, and from there, he’d go to Israel. After an hour of walking in the dark, he began to feel regret and fear and not a little panic, and so he decided to turn back to the station and return home.

“The next morning,” he recalls, “I was very angry at myself for losing my nerve. How could I have left and then come back? I decided to set out again, this time with no plans to return.”

Shlomo would make several more attempts, but each time something else foiled his plans, and he wound up returning. But life was getting more unbearable, thugs would walk the streets calling for the murder of Jews in cold blood, and the fear was palpable. And so, one day before Shavuos of 1963, Shlomo resolved that this time he would succeed. First, he hung a picture of his bar mitzvah celebration so that his family should have a memento of him. He put on the gold watch that he had received for his bar mitzvah, stuffed some cash into his pockets, and set out again.

This time he got off at Zabadani determined to forge ahead. It was lunchtime, and he walked along the abandoned tracks that were concealed by high grass and weeds.

“I walked for about two hours,” he says. “Suddenly I noticed a young man following me. That was a bad sign. No one had anything to look for in this place, and the fact that a young boy was in such a place triggered a red light. He asked me what I was doing, and I told him that my parents had traveled to Lebanon, and I had vacation from school so I wanted to join them until the end of vacation, but that I didn’t get a permit.

“I guess he believed me, or maybe it didn’t really make a difference. Either way, he explained that the route I was on would lead me straight into the arms of the border patrol, but as his uncle worked for the border police, he knew the weak points and would tell me which way was good to go. ‘Now it’s late,’ he said. ‘Come sleep in my house, and in the morning I’ll take you to the border.’ I went with him — did I have another choice?”

Looking back, Shlomo says he was quite frightened, but there was also a measure of security. “I had no room for any more fear,” he relates. “And this was just one more in the string of angels Hashem sent me along the way.”

The next morning, the two of them set out. “We walked for five hours on tough, mountainous terrain. In front of us was a mountain range that looked like it went on forever. And then my escort stopped and said: ‘From here you continue alone.’ He warned me to walk straight. Any deviation would return me to Syria.

“Before we parted, he asked for payment — he just expected he’d get something for his efforts, so I gave him my gold watch.”

Shlomo continued walking for several more hours, keeping close to the trees so he wouldn’t be detected by the patrols.

“I was terrified. I cried as I walked. I was cold and hungry; I hadn’t taken any food with me. I snacked on the carobs that grew on the trees.”

Shlomo’s father’s passport was stamped with the red “Jew;” and his ID card stated, “son is missing,” which put the entire family under suspicion

Shipped Away

But the miracle happened. As the sun began to set, he reached Lebanon. He didn’t know that he’d already crossed the border and just kept on walking through the hills, until he came upon an elderly farmer riding on a donkey. He waved, signaling for the man to stop. The farmer was stunned. How was a boy wandering around in these desolate mountains?

“I’m Syrian,” Malach explained, “and I’m trying to cross the border to visit my parents in Lebanon,” he repeated his story. The farmer looked at him with pity and told him to get onto the donkey, telling him that he’d long crossed the border and was out of range of the border patrols.

“We rode for two hours until we reached his house. He offered me a bed and made me food,” Shlomo relates. “He told me that tomorrow, he’d take me to a bus to Beirut. I was very happy because my mother had a sister and brother living in the Abu Jamil neighborhood of Beirut. This way, I could go to them and then continue on to Eretz Yisrael. In the morning, the farmer took me to the bus to Beirut. I gave him the rest of my money in return for his help, keeping what I needed for the trip.

“A few hours later, the bus reached Beirut. After wandering around a bit, I found a taxi and asked the driver to take me to the Abu Jamil neighborhood. As soon as I spotted a beit knesset, I told the driver to stop. I got out of the car and went inside.

“The mitpallelim saw a stranger and began to question me about where I had come from. When I told them what I had just been through, there was a great tumult. They brought me to the rosh kahal and then to the rav, who asked if I had relatives here. When I responded that I did, he quickly went to fetch them. But the rosh kahal warned my uncle not to let me leave the house, so that no one outside the community would know of my existence.”

At that time, Shlomo’s parents were frantic with worry. They searched for him everywhere, and after a few days, they legally had to report his absence to the authorities. The family was arrested and interrogated — the authorities wanted to extract information from them how Shlomo had run away. When the authorities were finally convinced that the family knew nothing, they were released.

Soon, they got a message from their family in Lebanon: Shlomo was with them. “Abba was very angry that I put everything at risk. He ordered me to wait in my uncle’s house for a smuggler who would come take me back to Syria. But I refused. At this point, nothing was going to stop me from getting to Eretz Yisrael.”

Rumors of the young boy who had smuggled across the Syrian border were met with astonishment by the Syrian Jewish community. For years, no one had dared try to run away, and then they heard that a teenager had crossed the border himself. Soon after, another six bochurim followed the same route, but Shlomo’s uncle, who hosted him, began to fear for his own family’s safety. The Mukhabarat, whose prestige was badly damaged by Shlomo’s escape, sent field agents to wherever they thought he could be, determined to bring him back to Syria at all costs, in order to stanch the new wave of border smuggling.

His uncle knew very well what could happen to them if they would be caught, and the arrival of six additional bochurim added to the fear of Beirut’s Jews. The heads of the community got together to find a solution to this messy situation. Until they did that, the young men were housed in a storage room on the roof of the Jewish school. Iliya Alber, the community head, activated his connections with the Jews of Eretz Yisrael to try to smuggle the boys across the border, but the Mukhabarat siege on the Jewish neighborhood was very tight.

“We were holed up in that crowded attic for about eight months,” Shlomo Malach remembers. “When winter came, we all got sick. We decided that if the community couldn’t help us, we’d have to help ourselves. Because I was the smallest and least conspicuous, I went to walk around in the city to look for escape routes.

“When nothing came up, I decided to go down to the port to try and find a way out by sea. I found work there as a porter, unloading huge sacks of salt from incoming ships, all the while keeping my eyes and ears open to hear about anything that could be useful for us.”

One day, Shlomo noticed an Italian passenger ship docked at the port, and tourists boarding it. The ship, then called the Willem Ruys but which would later be known as the Achille Lauro (whose name went down in infamy after being hijacked by the PLO in 1985), seemed to beckon.

“I had this crazy idea to sneak onto the ship and escape,” he says, “but there was a sailor standing at the entrance to the ramp carefully checking the documents of each passenger. But just then, there was a clash between hamoulas [tribal families] which turned into a gunfight. The tourists standing near the shops fled in panic, and from my hiding place, I saw that the sailor was letting them board without presenting their documents. I took advantage of the chaos and, as there was no one to stop me, dashed onto the ship.

“I looked around for a place to hide and noticed the covered lifeboats on the deck. I climbed into one of them and took cover. Night fell. Suddenly I heard a long horn. I peeked out and saw the lights of the port growing more distant. I finally fell asleep. In the morning, I awoke and walked with the rest of the tourists into the dining room, to find some fruits and vegetables.

“When I saw that the guard didn’t let anyone into the dining room without a ticket, I beat a quick retreat. I wandered around on the deck, and at night, I returned to hide in the lifeboat, emerging to quickly rummage through the trash to find a bit of food. That worked for a few days, until one time I came out to forage for food and the deck guard noticed me. He grabbed me and asked why I was looking for food. Having no choice, I told him that I was a Lebanese citizen and that I had gotten caught in the crosshairs of the fight on the docks, had boarded in panic and hid on the ship, which had suddenly set sail. He brought me to the captain’s room, and the captain began to question me.

“I didn’t tell them I was Jewish, but instead presented myself as a Maronite Christian named Antoine Kassoulani. I knew that there was a large community of Maronites in Lebanon and assumed it would sound reasonable. He told me that he’d return me to Lebanon, but I was happy to hear that it would take many months yet because the ship was on a long voyage around the world.”

The Achille Lauro ship, then called the Willem Ruys, nearly brought Shlomo to a watery grave

Deep Dive

Shlomo spent his days working in the ship’s kitchen, washing dishes and peeling vegetables. At night, he was given a tiny cell to sleep.

“When we got to the Port of Suez, they locked me in the cell,” Shlomo relates. “The captain reported to the Egyptian authorities that he had a stowaway on board. An Egyptian policeman boarded the ship to make sure I didn’t leave my room until we were once again sailing on the open sea. Each time we approached a port, I was locked in my cubicle until we moved away from the territorial waters of that country.”

The ship continued on around the globe, passing through Africa, Europe, the Far East, and Australia, from where it would head back to Lebanon. He knew that if he were to return to Lebanon, the authorities would arrest him and hand him over to the Mukhabarat — who in turn would torture him to death.

He needed an escape plan.

“I knew that if I wanted to save myself, I had to take action before it was too late,” he says. “I found a saw and sneaked it into my room, and each night, I sawed a little bit at the thick bars that covered the window. By the time land came into view, the bars were almost disconnected.

“We approached the port of Sydney, and again I was locked into my room. But this time, I wouldn’t be staying inside. When the ship docked, I punched the bars and squeezed through the small window. It was really a totally crazy idea. My cubicle was on the upper deck of the ship, nearly four stories above the water level — but if I was scared, my fear of the Mukhabarat was greater. I closed my eyes, stuck my head out, and then managed to get my whole body outside. I gripped at the window frame for a minute, and without thinking, I leaped into the water, and to freedom. Or so I thought.

“The miracle was that I didn’t jump earlier, before we got to the port. I only found out later that the area is crawling with sharks.”

Now the problem was getting out of the water. The pier was built on high columns, and as he tried to climb them, police boats swarmed the pier. Someone had noticed a man jumping into the water and alerted the police.

“I grabbed onto one of the columns and hid behind it, and after a few hours, the search quieted down. I clambered up onto the pier and walked toward the exit of the port. I was happy to notice that the ship was preparing to set sail, but I wasn’t careful enough. The guard standing at the entrance to the port noticed this waterlogged young kid and had me detained.”

After a few days in prison, a car came to fetch him, and after a short drive, Shlomo found himself at the entrance to a Maronite Christian church. The bishop heard about a young kid who’d jumped off the ship and claimed he was a Maronite from Lebanon and wanted to see for himself.

“He offered to adopt and convert me, and I would get Australian citizenship and a home and safety. But I knew I was a Jew. I studied in cheder. I knew I wasn’t even allowed to be in this building. But I was also intimidated, so I told him I needed a few days to think about it. Finally, I told him that I really want to go back to Lebanon to my family.

“But I made a big mistake then, that could have saved years of pain and torture. Because when they found me, a swarm of journalists came to interview me. Had I told them the truth, that I was a Jew who’d escaped Syria and was trying to get to Eretz Yisrael, I’m sure the Israeli consulate, the Mossad, somebody — would have come and helped me. But I was just a scared kid and decided to stick to my story. And so, in the end, the Australian police put me back on a ship to Lebanon.”

In fact, it was the same ship. The vessel had traveled to Melbourne and was now back in Sydney.

“I was led onto the ship under heavy guard. The captain was fuming at the escapade I’d pulled, and I was put in a locked room under heavy guard. Finally, after a few weeks, I got to Lebanon, exhausted. Because I claimed I was a Lebanese citizen, a detective was brought onto the ship, and he began to ask me questions. In the end I was so exhausted that I told them the partial truth — that I was a refugee from Syria, but I didn’t say anything about being Jewish,” Shlomo relates.

“When they asked me if I had relatives,” he continues, “I told them my uncle’s name. They brought him to identify me. He looked at me with a hostile expression and told the interrogator that he didn’t know me. ‘He’s Syrian and I’m Lebanese,’ he said, and left the room. I was silent. I knew that he had recognized me, but had he said so, we’d both be in danger.”

The detective left the room and told the captain that they could not allow me entry into Lebanon, and that I needed to be returned to the Syrian authorities. The captain got angry at the detective, and they began to shout at one another. The captain claimed that I had boarded in Lebanon, and I had to get off in the same country. “How am I supposed to bring him to Syria? There’s no sea there!” the captain shouted to the detective. “This is where he got on, and this is where he’ll get off!”’

Despite this diplomatic mini-crisis, the Lebanese immigration services didn’t soften their stance. They also assigned guards to the ship to make sure Shlomo didn’t go anywhere. And then the ship set sail.

“I had no idea what they were planning to do with me. I sat on the floor of my room, gazing out of the porthole into the sea.

“I thought about myself, by now a 15-year-old, alone and abandoned at sea. I had been wandering the world for so many months, and I was so close to the land I yearned for — maybe just a few kilometers away — and yet still so far. Now, for the first time, I truly felt that I didn’t know what to do. All I could do was pray. I sat for several hours like that, my head between my knees, sailing against my will without knowing where to.

“When I raised my head, I found a dozen people surrounding me, and they didn’t look too friendly. ‘It’s been decided to throw you into the sea,’ one of them said flatly. I fought them off in the beginning, but then I had no more strength. So I asked for a lifejacket, they gave me one, and I jumped.”

Shlomo Malach closes his eyes, trying to flash back to those moments. “My head was empty. No thoughts, no despair, and no self-pity. The only thought I had was to try and get to the nearest coast. The moment they threw me overboard is probably the hardest moment I’ve ever experienced.”

But then, alone among the waves, his thoughts switched. “I knew I needed to swim against the direction of the ship and not get caught in its current. I really have no idea how long I was in the water, when I spotted a fishing boat. I waved, and thankfully the crew noticed me. Although they took me out of the water and saved me, I had fallen from the frying pan into the fire. They handed me right over to the police.”

Now that they had him, they began a round of intense interrogations. “I finally broke,” says Shlomo, “and told them the truth, that I was a Jew. They began to grill me intensively, and pressured me to admit that Iliya Alber, the community leader, was an Israeli spy. When I refused, the brutal torture began.”

Every day, they used different torture innovations.

“They took a long screw, heated it up in front of my eyes, and then stuck it into a muscle in my leg. Despite the excruciating pain, to the point of fainting, I didn’t cooperate. They gave me electric shocks, drowned me in freezing water. Once they took me to the top of a hill, tied me into a tractor tire, and pushed the tire down the hill, where it rolled over and over with me inside. But still, I didn’t cooperate.”

Shlomo was imprisoned for close to a year — a young teenager among dozens of seasoned criminals — when the Jewish community in Lebanon learned that at the end of his prison term, he would be extradited to Syria — which would mean certain death. In the end, the community leaders — perhaps with some Mossad involvement — managed to bribe the interior minister to give him a temporary transit visa good for two weeks, which he used to go to Turkey.

Shlomo arrived in Turkey and hurried to the Israeli embassy in Istanbul. The ambassador was horrified by his story, quickly arranged for him to make aliyah, and even personally accompanied him back to Israel.

In 1966, after surviving unspeakable torture and anguish, Shlomo Malach finally fulfilled his undying teenage wish. In Israel, he was initially warmly welcomed. “We heard about you,” the debriefing officer related, “and we really admire your courage. We will take care of you so that you lack for nothing.”

A family reunion after 30 years. “When the Jews were finally allowed to emigrate, my family went to Brooklyn. I guess I was the only one born with Zionist blood”

On His Own

Malach was recognized as a Prisoner of Zion and was initially embraced by relatives who were already living in Israel. But it was the period of the famed “austerity,” when all supplies were rationed and everyone struggled, and Shlomo Malach soon found himself all alone, sleeping nights in public parks during the summer, and in buses parked at the depots during the winter. He admits he was a difficult person then — alone, depressed, suspicious, hostile, anxious. He applied for early enlistment in the army, primarily so that he would have a stable structure. He got the structure, but he didn’t get the support he needed and craved. And after he was thrown into military prison for falling asleep during guard duty, he realized that the army couldn’t take away, or even help him through his trauma. Still, he did his service for the country he sacrificed so much to get to, giving 20 years to reserve duty even though he’d received an exemption, fighting in both the 1967 Six Day War and the 1973 Yom Kippur War.

Shlomo, who today is retired and volunteers in a soup kitchen for the needy, wanted to get past his trauma, move on, and have a “normal” life. The only way he could do that, he says, was by turning off all the memories, blocking everything out. That was his method of therapy. He worked in construction and in various factory jobs, met a nice young woman named Yona, moved to Holon outside Tel Aviv, and built a family. Today he’s affiliated with the Chabad shul in Holon and considers Rabbi Yochanan Gurary, who is also Holon’s chief rabbi, as his spiritual mentor.

Shlomo says he thinks he was the only one in his family “born with Zionist blood.” Seven siblings moved to Brooklyn, as did his parents, when emigration was officially permitted in the early 1990s. Once his family was able to emigrate, he made sure to see them at least once, sometimes twice, a year. But until then, he didn’t see his mother for 17 years after he’d escaped and made his way to Israel.

In his first year in Israel, Shlomo Malach would communicate with his parents through someone he knew who lived in France, who would pass along his letters — but those letters, and the answers, were few and far between: Sometimes it would take a year for a delivery and answer. And then, in 1980, 17 years after he escaped from Syria, he was finally able to briefly see his mother. She was permitted to travel to Istanbul for a week, where mother and son were finally able to reunite.

“I was in the lobby, and my mother was on the stairs when we saw each other,” Shlomo remembers, replaying the image constantly. “We were so stunned to see each other — she was crying at the top of the stairs, I was crying at the bottom, and we met in the middle. She wasn’t even sure it was me. I have a certain birthmark on my arm, and only once she saw it she knew for sure it was me.”

While Shlomo says the only way to forge ahead was to forget, “there isn’t a day I don’t think about those horrible years, not a night that I don’t think about the trauma in my dreams.” But still, he’s grateful — because not everyone merits to see open miracles, G-d’s hand carrying him through the unimaginable.

“My entire journey was a series of miracles,” he says. “I was transferred from one hand to another.” He remembers the horrors, the months of torture in a prison that could have killed most people, the near-drownings. But one thing that he doesn’t forget is to be thankful for every minute of life since.

“I know clearly how I was saved throughout this crazy journey that I took. It was only the chesed from Above. In every place where I should have been finished off, and later when I was alone with no one to care for me, I received Heavenly compassion. I still am.”

—Rachel Ginsberg contributed to this report.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 912)

Oops! We could not locate your form.