Johnny Hates to Read

The current generation of high school and college students do not read

I

recently watched a clip of a group of American college students frolicking on a Florida beach during spring break. They were asked a number of questions, and their answers could easily make one despair of America’s future.

First question: Who was the Revolutionary War fought against? No clue.

Second question: Who were the two sides in the Civil War? Here at least one of the college students ventured an answer: “Let’s see. It’s called the Civil War. So, it must have been the civilians against whomever was in power.”

In addition, none of the “students” (of what? one wonders) could say how many senators there are.

Where could such comical ignorance have come from?

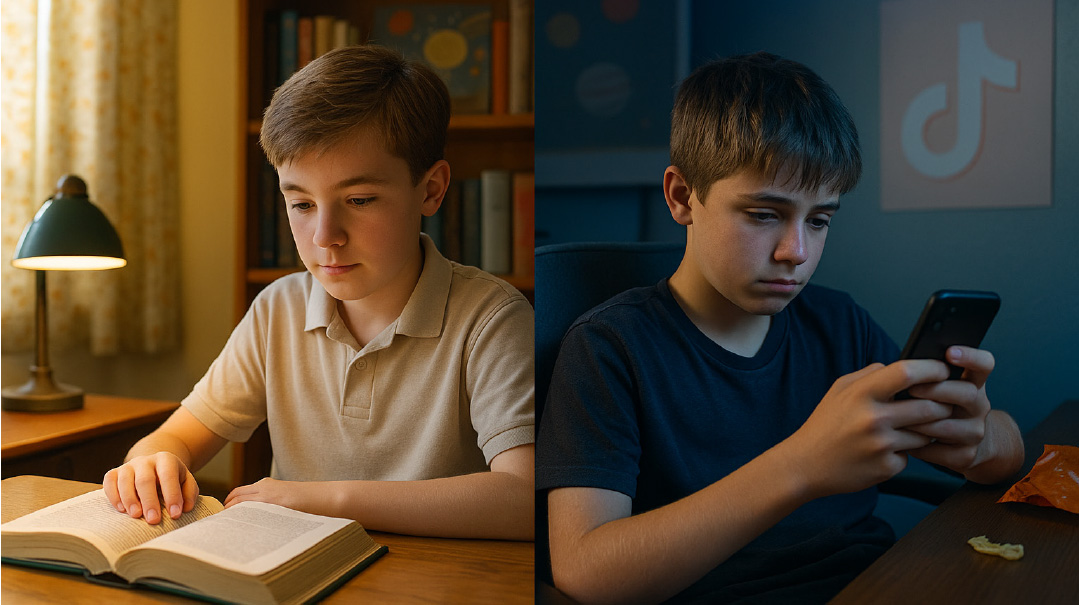

One explanation is that the current generation of high school and college students do not read, and many are functionally illiterate in terms of being able to understand the content of a simple paragraph. Secondly, the academic demands upon them have been so dumbed down that the term “higher education” has been drained of meaning.

We recently hosted for a Shabbos meal an intelligent 17-year-old bochur, who told me, without embarrassment, that he hates to read, and that is true of his entire generation. The statistics seem to back him up. In 1976, 40% of 12th-graders read at least six books for pleasure in the course of the year. In 2021–22, even in the midst of Covid, that number dropped to 13%. In 1976, only 11.5% of 12th-graders had not read a book for pleasure in the preceding year. Today it is over two-fifths.

Last year, the Atlantic reported that many students, who do not read much, find it difficult to attend to details while keeping track of the plot. Complaints by college professors about students’ inability to comprehend even relatively straightforward paragraphs are legion. A professor at North Central College in Naperville, Illinois writes at Slate that he used to assign approximately 30 pages of reading per class. But if he assigns anything over ten pages today, the students tell him that the reading burden is unbearable.

Consider what it means to hate to read or to find it difficult to do so. One of the few poems I can remember from elementary school is Emily Dickinson’s “There Is No Frigate Like a Book.” And that is certainly what books were for me growing up — a frigate to faraway places. To have no interest in reading betokens a lack of intellectual curiosity about anything beyond one’s narrowly circumscribed boundaries and in anything that cannot be absorbed visually in an instant, almost without transiting the brain.

Fiction, especially good fiction, allows us entry into the thoughts and feelings of those of backgrounds and personalities different from our own. Nonfiction helps us learn about how our world works through books of psychology and sociology and a variety of other disciplines and how it has changed intellectually and materially over the centuries. From biographies, of which I consumed an inordinate number as a child, we gain inspiration from great lives, while also learning that there are few lives without their bumps and stumbles.

THE MOST OBVIOUS CULPRIT behind the lack of interest in books and magazines is the explosion of handheld devices programmed to provide neural rewards with little effort. Frederick Hess of the American Enterprise Institute reports that in the 1960s, full-time students at four-year colleges spent 24 hours a week studying. In 2022, 70% of such students were devoting less than ten hours a week to studying, even though they are much less likely to hold down jobs than were than students in previous generations.

So what do they do with their time? Two researchers estimated in 2023 that college students spend an average of seven hours a day on their smartphones, and that they pick them up 113 times a day. That is addiction.

A second factor is declining standards. Students and professors have entered into a symbiotic relationship in which each expect and seek less and less from the other, with the result that students spend less time learning and faculty spend less time teaching. Universities, according to Hess, attract star faculty, in part, by offering them reduced teaching loads.

As teaching loads have declined dramatically, universities have been forced to hire more faculty, sending costs skyrocketing. Many of those faculty are non-tenure-track adjuncts, who are overworked and underpaid, and thus have little time to mentor students. Bottom line: Students pay more for less — less chance to learn from senior faculty, and fewer mentoring activities, such as I once enjoyed with numerous faculty members.

A second factor in reduced expectations from students, with the predictable results, is the woke war on standards. And no group has been harder hit than minority and disadvantaged students. Robert Pondiscio tells the story in the June Commentary (“How Wokeness Destroyed an Education Miracle”). The miracle was a group of inner-city charter schools that emerged in the late 1990s: KIPP (Knowledge Is Power Program), Achievement First, Uncommon Schools, YES Prep, and Noble Schools.

They were characterized by strict discipline — school uniforms, homework assignments every night, a requirement to sit up straight, with eyes tracking the teacher — and impressive results. Studies from Stanford University’s Center for Research on Education Outcomes showed that students in the new charter schools gained an annual equivalent of 40 extra days of learning in math and 28 in reading. Soon anecdotes of students emerging from inner-city housing projects and entering Ivy League campuses began to proliferate.

But then came the woke backlash. The schools were adjudged too strict, too militaristic — in short, “too white.” A white diversity trainer, Tema Okun, labeled traits such as “perfectionism,” “a sense of urgency,” “worship of the written word” — meaning reading and writing — as reflecting a “white supremacy culture.”

The education reform movement, writes Pondiscio, was founded to remedy the stubborn “achievement gap” between white and black students. But as it began to do so, the very concept of an “achievement gap” was cited as an example of “centering whiteness.”

In short, instead of kids being given the tools to compete and succeed, and the satisfaction that goes with overcoming odds — i.e., equality — critics of the movement demanded “equity,” equal results. And the means of doing so was to get rid of standards and abandon such “white” concerns as discipline and hard work.

The fundamental assumption of critics was racist — black and minority kids can never succeed on their own. At the university level, that resulted in the creation of rinky-dink academic ghettos — gender studies, black and ethnic studies — where minority students could nurse their sense of grievance.

Doug Lemov, one of the leaders of the educational reform movement, returned to what had once been a stellar charter school, where parents could send their kids knowing they would be physically safe and their education taken seriously. He found utter chaos, and was told by administrators that they were not really sure adults should be telling young people what to do.

His conclusion: “Whatever systems of oppression you think you’re dismantling, they’re a lot less oppressive than the chaos going on in this school right now. And you should reassemble them as quickly as possible.”

AS I WAS COLLECTING material on the depressing state of American higher education, I read Roosevelt Montas’s memoir Rescuing Socrates: How the Great Books Changed My Life and Why They Matter for a New Generation. Montas entered Columbia University a mere six years after arriving in America from the Dominican Republic, speaking no English. He went on to become a senior lecturer at Columbia and director of its Center for the Core Curriculum. That core curriculum is based on a reading list of great or important books in the Western canon studied by all Columbia undergraduates in small discussion-based classes.

Montas’s own intellectual journey began when he found a set of the Harvard Classics discarded by a neighbor in the Corona neighborhood of Queens. From the pile, he selected Volume II, which included three Platonic dialogues. Subsequently, John Philippides, a teacher at John Bowne High School, whose students spoke 51 different languages, noticed him reading Plato and engaged him in discussions of the dialogues.

Philippides, himself a childhood immigrant from Greece, had made his way to Princeton and enjoyed a successful career in business before embarking on a second career teaching the next generation of immigrant youth at John Bowne. He directed Montas to Columbia and has remained a father figure to him ever since.

Alfred North Whitehead famously described all Western philosophy as footnotes to Plato, and not surprisingly Montas’s celebration of the great books begins with Plato’s teacher Socrates. Sentenced to death by an Athenian court for corrupting Athenian youth, Socrates was offered amnesty if he would cease and desist from his philosophical pursuits. He refused on the grounds that he had been commanded by the gods “to live the life of a philosopher and examine myself and others.” His first question to his fellow citizens was: “Are you not ashamed of your eagerness to possess as much wealth, reputation, and honors as possible, while you do not give thought to wisdom or truth, or the best possible state of your soul?”

The liberal education that Montas defends was once defined by Leo Strauss as “listening to the conversation of the greatest minds,” with respect to the nature of the good life and how to attain it. But, writes Strauss, we must create that conversation, since the greatest thinkers deliver monologues. It is up to latter students to fashion those monologues into conversations by highlighting the arguments between those monologues, and judging the arguments ourselves, without taking any of them on trust.

Understandably for Montas, in light of his personal history, he rejects the claim that fashioning that conversation is a luxury suited only to the well-to-do, with plenty of time on their hands. For more than a decade, he taught the three dialogues around Socrates’ trial and subsequent death to high school seniors from disadvantaged backgrounds. Many of them related to Socrates’ words passionately. From Socrates’ relentless drive for self-knowledge, they experienced the “revelation of the self as a primary object of lifelong investigation” and the necessity of viewing “ordinary human experience with critical self-awareness.” Of the 300 or so students in the program, almost all went on to college and many to graduate school.

BUT WHAT DOES the state of classical liberal arts education have to do with Mishpacha readers, whose concerns are more centered on Torah wisdom and its tools for self-examination and self-actualization? Since much of my personal focus is with baalei teshuvah, I would answer as follows:

Which young, secular Jew is more likely to be drawn to Torah — one who has devoted serious effort to contemplation of the purpose of life, and views that inquiry as fundamental, or one who has not? Who is more likely to give Torah a hearing — one who has been taught reverence for ancient wisdom, or one who dismisses the great books as the products of “old white men”? To whom will Torah speak — one whose interests encompass the full range of human experience, or one whose concerns end at the tip of his or her nose and with the fulfillment of desires experienced primarily as involuntary itches?

And finally, who will be more susceptible to lies foisted upon them by professors more interested in ideological indoctrination against Jews, Israel, and traditional religious views, than in educating them to think critically — one who has never engaged in serious thinking of any kind and compared and judged rival arguments, or one who has?

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 1065. Yonoson Rosenblum may be contacted directly at rosenblum@mishpacha.com)

Oops! We could not locate your form.