J’Accuse… Again

France claims to remember The Dreyfus Affair, but reality proves otherwise

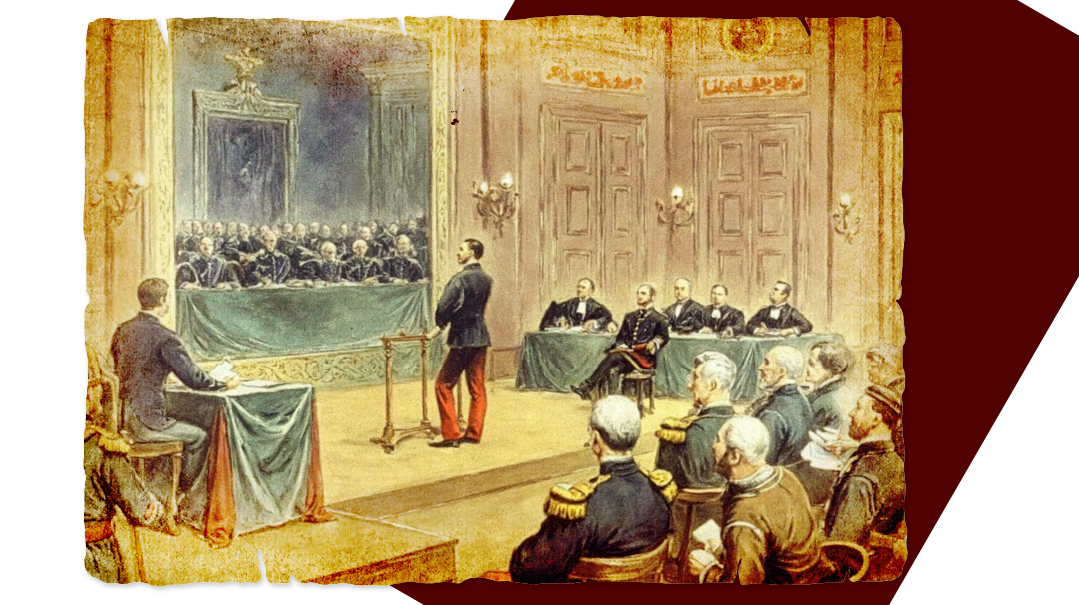

When Georges Clemenceau — future Prime Minister of France and, at the time, editor-in-chief of the newspaper L’Aurore — sat down to plan the January 13, 1898, edition of his daily, he made a fateful decision. On an average day, L’Aurore printed 30,000 copies. That morning, however, Clemenceau ordered a print run ten times that amount. Three hundred thousand copies would be distributed across Paris — an audacious gamble, perhaps, but one that would succeed in rattling the very bones of the French Republic.

It may be a bit much to say that Clemenceau foresaw that the moment would become historic, as it did. But he surely sensed the explosion it would trigger in an already volatile society. The Dreyfus Affair had reached a boiling point. Just two days earlier, a military court had acquitted the actual traitor — the man who had transmitted confidential military documents from the French army to the German embassy in Paris. Meanwhile, Captain Alfred Dreyfus, a Jewish artillery officer from Alsace, remained the scapegoat, falsely accused and already exiled to the notorious Devil’s Island.

That bitter January morning, Parisians opened their newspapers over breakfast and found a thunderclap on the front page: an open letter by Émile Zola, one of the most celebrated literary figures of the era, in which he mounted a direct assault on the president of the Republic, Félix Faure. Zola’s voice — piercing, indignant, unrelenting — articulated what many had long suspected but feared to say aloud: that Dreyfus had been sacrificed at the altar of military honor and nationalist prejudice.

The letter’s title, “J’Accuse…!”, now immortalized, was reportedly chosen by Clemenceau himself. In just two words, it summoned the full moral authority of the French intellectual tradition against the machinery of political corruption. Zola accused the generals, the ministers, the judges — and the very soul of the Republic.

In time, truth emerged victorious. Dreyfus was eventually exonerated, reinstated into the army, and awarded the Legion of Honor. Yet the stain of anti-Semitism has lingered in the French conscience ever since, stubborn and unresolved.

Now, 130 years later, France finds itself once again wrestling with that legacy. While President Emmanuel Macron’s party is proposing to officially commemorate the Dreyfus Affair, in the same breath, Macron announced that France will formally recognize a Palestinian state — a move widely perceived as a tacit reward for Hamas in the wake of the October 7 massacre. Meanwhile, anti-Semitic attacks have once again become common on the streets of Paris.

Can France, home to half a million Jews and the cradle of liberté, égalité, fraternité, finally break with its long history of anti-Semitism? Or is it still trapped in the same moral maze that Zola exposed more than a century ago?

The term “Dreyfus Affair” is familiar to many, though few can recount its details. And while there are a plethora of written works about the case, it never hurts to revisit its outlines — especially at a time when anti-Semitism is enjoying a grim resurgence.

The year was 1894. Captain Alfred Dreyfus, a 35-year-old artillery officer in the French Army, appeared to be on a path of upward mobility. By all accounts, he was capable, intelligent, and loyal — a promising figure within the military elite of the Third Republic. But the illusion of stability was shattered by a single letter.

A French spy, employed as a cleaning woman at the German embassy in Paris, stumbled upon a memorandum detailing confidential French military secrets. The conclusion was obvious: There was a traitor within the army, someone passing artillery secrets to Germany. Based on the contents of the letter, investigators concluded that the author had to be someone familiar with military operations — likely someone associated with the General Staff.

Enter Alfred Dreyfus. He fit the bill, albeit loosely. He had worked with the General Staff, he specialized in artillery, and — critically — he was Jewish. That last fact, in an era of mounting nationalist fervor and open anti-Semitism, made him a convenient target. Though handwriting experts noted discrepancies between Dreyfus’s script and the letter in question, others claimed the similarities were close enough. A presumption of guilt began to calcify.

On October 13, 1894, Dreyfus was arrested. There was no concrete evidence against him. Officials pressured him to confess; at one point, they even left a revolver in his prison cell, subtly encouraging suicide. But Dreyfus refused. “I want to live to establish my innocence,” he declared.

The case ignited a national firestorm. French society began to polarize. Some newspapers — driven by xenophobia and anti-Semitic rage — labeled him a traitor to the nation. Others, such as L’Aurore, questioned the opaque judicial process and the motives behind it.

On December 22, 1894, a military court of seven judges unanimously sentenced Dreyfus to life imprisonment for “collusion with a foreign power.” He was stripped of his rank and subjected to la dégradation militaire, a ritual public humiliation. On January 5, 1895, he stood in a courtyard as an officer snapped his sword over his knee and onlookers screamed, “Death to Judas! Death to the Jew!” Days later, Dreyfus was deported to Devil’s Island, a remote penal colony off the coast of French Guiana, known for its brutality and isolation.

But one man refused to let the matter rest: Alfred’s brother, Mathieu Dreyfus, began a dogged, self-financed campaign to clear Alfred’s name. His efforts coincided with a twist of fate: In 1895, Colonel Nicolas Jean Sandherr, the virulently anti-Semitic head of military intelligence, fell ill. His replacement, Major Georges Picquart, stumbled upon evidence that had never been presented in Dreyfus’s trial.

Picquart uncovered correspondence between the German military attaché, Maximilian von Schwartzkoppen, and a French officer named Major Charles Marie Ferdinand Walsin Esterhazy. The handwriting on the original incriminating letter matched Esterhazy’s far more closely than Dreyfus’s ever had. The real spy had been hiding in plain sight.

Armed with this revelation, Mathieu intensified his campaign, joined by a growing chorus of intellectuals and political figures. Public pressure led to a new trial — not for Dreyfus, but for Esterhazy. Hopes ran high. But the outcome was a farce. In less than two days, Esterhazy was acquitted. The backlash was immediate.

France split in two: the ‘Dreyfusards’, who demanded justice, and the ‘anti-Dreyfusards’, who saw any challenge to the military verdict as a betrayal of national honor. This camp was led by Edouard Drumont and the anti-Semitic La Libre Parole newspaper. The social rupture grew so severe that, by 1899, the Supreme Court was compelled to reopen the case. Dreyfus, who had spent years in near-total isolation, was brought back to testify. Once again, he was convicted — though this time the sentence was reduced to ten years.

Faced with a nation on the brink of civil unrest, the government opted for a compromise. Dreyfus was offered a presidential pardon — on the condition that he admit guilt. It was a painful decision. For a man who had stubbornly maintained his innocence, the moral price was steep. But the political machinery had spoken. President Émile Loubet signed the pardon.

It wasn’t until 1906 that justice caught up with history. Dreyfus was fully exonerated and reinstated into the military. He would go on to serve with distinction during World War I and live quietly until his death in Paris on July 12, 1935, at the age of 75.

IN France, the story of Alfred Dreyfus is etched into the national conscience. The subject is taught in the vast majority of schools, and the name Dreyfus evokes a chapter of the Republic that still stings — a tale of injustice, betrayal, and public disgrace, centered on a man whose only crime was being Jewish. It is a source of collective shame, and perhaps for that very reason, President Emmanuel Macron and his Renaissance Party have turned to Dreyfus’s legacy as a way of countering growing accusations of anti-Semitism that have dogged their government in recent years.

Their attempt came in the form of two closely linked gestures.

First, a group of lawmakers from Macron’s party put forward a “reparative measure” to posthumously promote Captain Dreyfus to the rank of brigadier general. The initiative, introduced in early June, passed unanimously in the National Assembly, with all 197 members of the lower chamber voting in favor. The Senate is expected to follow suit.

“The Dreyfus Affair remains a powerful symbol of the fight for justice and against state injustice,” Shannon Seban told Mishpacha. “Raising Alfred Dreyfus to the rank of brigadier general will be an act of justice and recognition of his exemplary merit.” Seban, who serves both as president of Macron’s Renaissance Party in Seine-Saint-Denis and as a city council member for Rosny-sous-Bois, has played a visible role in championing the project.

Seban occupies a politically fraught position: She is the most prominent Jewish face of a party many Jews now believe has abandoned them, and is acutely aware of the pressure to answer for the party’s increasingly strained relationship with the Jewish community — which once voted for Macron in considerable numbers. In our conversation, she emphasized the symbolic importance of the initiative in the face of a rising tide of anti-Semitism across the continent.

“This posthumous promotion will be a concrete expression of our commitment to the rule of law,” she said, “and a clear affirmation that the French Republic is alive as long as it relentlessly defends equality and justice. And this comes in the context where anti-Semitism is rising in Europe and in France, especially after October 7, 2023. In France, for instance, we had a one-thousand percent rise in anti-Semitic attacks.”

A few days after the parliamentary vote, President Macron announced a second move. Beginning in 2026, July 12 — the anniversary of Dreyfus’s exoneration in 1906 — will officially be a national day of commemoration.

But to many, these gestures ring hollow — symbolic offerings meant to distract from a foreign policy increasingly at odds with Israel and, by extension, the Jewish community. Less than two weeks after the Dreyfus commemoration was announced, Macron made another headline-grabbing proclamation: This month, France would officially recognize a Palestinian state at the United Nations. In Jerusalem, the reaction was swift and severe. Prime Minister Binyamin Netanyahu accused Macron of “rewarding Hamas’s terrorist actions” by legitimizing their broader political aims in the wake of the October 7 massacre.

“There is a fundamental contradiction in the French government’s relationship with the Jewish community,” said Jean-Yves Camus, a political analyst and expert on Jewish affairs in France. “On one hand, they honor Captain Dreyfus. On the other, they openly punish Israel. And that dissonance isn’t lost on anyone.”

Camus is blunt in his assessment. “The average French citizen today does not believe that Dreyfus was guilty. So, let’s be honest — the reason they’re doing this now is quite clear. It’s a signal to the Jewish community: ‘We see you.’ But what does that even mean when, at the same time, we have our foreign minister [Jean-Noël Barrot] accusing Israel of every imaginable sin? You can’t use Dreyfus to cover that up. It doesn’t work.”

Emmanuel Macron was elected President of France in 2017, and if the term “Jewish vote” carries any political weight in the Fifth Republic, then it leaned overwhelmingly in his favor. At just 39 years old, the fresh-faced, eloquent centrist was widely seen as the most viable alternative in a tense runoff against Marine Le Pen, leader of the far-right National Front. At the time, many Jews still placed their faith in the good intentions of the center-left. And with good reason: The Le Pen surname was, and remains, indelibly associated with French anti-Semitism — not so much because of Marine herself, but because of her father, Jean-Marie Le Pen, whom the party eventually cast out like a skeleton too ghastly to keep in the closet.

But then came the tragedy of October 7. The Hamas-led massacre in southern Israel sent shockwaves around the globe, and France was no exception. Macron, like many Western leaders, began with words of solidarity. In those early hours, he stood squarely with Israel. But as the days turned to weeks, the tone shifted, as did the position of the French state.

That support lasted a fleeting 32 days. On November 9, with Israeli forces still engaged in fierce combat against a well-armed Hamas and with Israeli hostages still languishing in captivity, Macron turned his ire not on the terrorists but on Israel’s Prime Minister. He urged Netanyahu to “stop killing women and children.” It was a turning point, and from that moment forward, the French president’s stance only hardened. Macron called on global powers to halt weapons sales to Israel. He condemned the Israeli military’s actions. He demanded Israel refrain from entering Rafah — a city whose name, once obscure to the French public, had by then become shorthand for geopolitical controversy.

When the head of state adopts an overtly anti-Israel position, it should come as no surprise that anti-Semitic sentiments in the streets begin to boil. And boil they did.

One also cannot ignore the demographic undercurrents shaping French politics. France is home to one of the largest Muslim populations in Europe, estimated at around nine-million people — nearly ten percent of the national population. This is the legacy of a long and tangled colonial past, particularly in North Africa. And for a president who has steadily hemorrhaged public support, this bloc now represents a political lifeline.

Pro-Palestinian demonstrations filled the streets, often under the passive watch of security forces. Jewish life in France began to withdraw into itself. Symbols of Jewish identity vanished from public spaces. Between 2023 and 2024, France recorded over 3,100 anti-Semitic incidents—including assaults, arson attacks on synagogues, acts of vandalism, and even murder.

The consequences were immediate. According to data from the Jewish Agency, thousands of French Jews had emigrated by the end of 2023. The aliyah rate jumped by 95 percent in 2024, and projections for 2025 anticipate at least 6,000 additional French Jews moving to Israel. While the numbers haven’t yet reached the dramatic peak of 2015 — when more than 7,000 made aliyah in the wake of the Hyper Cacher supermarket attack — they reflect something more troubling: not a spike, but a steady trend.

And these numbers only reflect those willing to take the leap. The sentiment runs deeper. A report presented to the Knesset’s Committee for Immigration, Absorption, and Diaspora Affairs found that 38 percent of French Jews are seriously considering emigration.

“Of course, I understand how difficult it is,” said city councilwoman Shannon Seban. “But to the Jews of France, I say: don’t leave. Because if you leave France — the country where most of you were born and raised — it means we’ve surrendered. It means the anti-Semites have won. And we cannot afford to give up.” Seban conceded that “being Jewish in France is a daily challenge,” but insisted on the moral imperative “to stay and fight against anti-Semitism.”

The sentiment may be stirring, but the frustration with Macron’s government continues to mount. For many Jews, these appeals sound hollow, particularly in the face of increasing hostility from the very state meant to protect them. “I’m not going to say that honoring Dreyfus is a bad decision,” said Jean-Yves Camus, the French political analyst. “But it’s not particularly useful either.”

What the Jewish community needs, Camus argued, is not symbolic gestures but concrete action. “Right across the street from where I’m speaking to you, just a month ago, a rabbi was attacked outside his home. The attackers are still at large. There are CCTV cameras on the entire block, and still — they haven’t been found. There are no consequences for crimes committed against Jews. That’s the real issue.”

So while Macron honors the memory of Captain Alfred Dreyfus — France’s most famous Jewish scapegoat — many Jews feel that the message comes too late, or rings too false. The Republic that once condemned Dreyfus has learned to commemorate him. But the question remains: Can it protect the Jews of today? Or has the lesson of Dreyfus become, yet again, a history France prefers to revere rather than to heed?

More than a century later, one cannot help but wonder: What if the Dreyfus Affair happened today? What if, instead of the 1890s, the trial of a Jewish officer accused of disloyalty unfolded in our fractured political moment, in the wake of October 7, with Israel and the Jewish people once again cast as subjects of furious debate?

The historical alignments are well-known. At the end of the 19th century, support for Dreyfus came primarily from intellectuals and writers — most famously, Émile Zola, as mentioned — as well as many on the center and left of the political spectrum. Opposition was clustered among the Catholic Church, the nationalist right, and those for whom the presence of Jews in public life represented an existential threat. It was an evolving process, but the broader pattern was clear: Intellectual cosmopolitans defended him, traditionalist nationalists condemned him.

To transpose that story into the present is to discover how much has shifted, and how much has remained.

In 1998, when France commemorated the centennial of the Affair, then-Prime Minister Lionel Jospin, a Socialist, remarked that “The Left was for Dreyfus and the Right was against him.” It was, in context, a statement of historical fact. Yet it sparked a furor, forcing Jospin to clarify that he did not mean today’s right would oppose justice for Dreyfus, only that this was the alignment in 1898. The sensitivity of that remark, even a hundred years later, revealed how much the Dreyfus Affair remained a mirror through which France saw its own present tensions.

And the mirror today reflects something stranger still.

If a new Dreyfus Affair were to erupt in 2025, would the same intellectual and left-leaning circles rally to the side of the Jewish defendant? Or would the positions invert? Since October 7, and the war that followed, the global intellectual left has grown increasingly hostile toward Israel, often extending its antagonism — subtly or otherwise — toward Jews in general. University campuses from New York to Paris have staged protests less against particular policies than against the very legitimacy of the Jewish state. The word “Jew,” once descriptive, is now hurled as an insult, often a thin veil for older prejudices.

The parallel is troubling. In the late 19th century, Dreyfus’s guilt was taken for granted by much of the right, for whom Jewish Frenchness was inherently suspect. Today, Israel’s guilt — in any conflict, regardless of the facts — is taken for granted by much of the left, for whom Jewish particularism is inherently reactionary. Then, as now, the question of Jewish belonging — whether to the Republic or to the modern liberal order — is the point at issue.

Consider the French political landscape. Emmanuel Macron, a centrist, has attempted to balance competing narratives, yet his recent endorsement of a Palestinian state, made while Israeli hostages remain in Gaza, struck many French Jews as a betrayal, and an attempt to appease France’s restive left and its significant Muslim population at Jewish expense.

“Obviously, Jews in France are deeply frustrated with Macron,” says Councilwoman Shannon Seban, the Jewish voice within the President’s party. “But still, I firmly believe that the center is the safest place for us.”

Yet when pressed about Macron’s comments regarding Palestinian statehood, Seban acknowledges the president’s misstep. “I belong to his party, but I’m first and foremost a free woman. And when I disagree with something, I say it. You can’t talk about recognizing a Palestinian state while there are still hostages in Gaza. That’s tantamount to recognizing Hamas as the victor. I don’t want terrorism to become a legitimate means for political negotiation.”

To Macron’s left stands Jean-Luc Mélenchon, the charismatic leader of La France Insoumise, who has fashioned himself into a tribune of anti-Zionism. His rhetoric, increasingly blunt, flirts with a language that many Jews recognize as anti-Semitic in effect if not in intent. The contradiction is glaring: A party that trumpets feminism and secularism allies itself, electorally if not ideologically, with hardline Islamist constituencies whose values oppose those very principles. But politics is a marketplace of votes, not of philosophical consistency.

And to Macron’s right stands Marine Le Pen, who has worked to launder her party’s image, rebranding the National Front as the National Rally and draping it in the flag of pro-Israel sympathy. Many Jews are skeptical about this pivot. Her party’s lineage is too close to Vichy, its ranks too recently stained by Holocaust denial and casual anti-Semitism. Yet some Jews, exhausted by the failures of the center and alienated by the hostility of the left, now look toward Le Pen’s camp with something like reluctant pragmatism.

The inversion is stark: The heirs of Zola’s camp now rail against Israel, while the heirs of Drumont’s camp profess solidarity with it.

Seban is unflinching in her critique of both, the right and the left: “The far-left has used the Israeli-Palestinian conflict as a tool to gain votes among the Muslim electorate. But we can’t ignore what’s happening on the far-right either. The National Rally was founded by people with ties to Nazism. Less than a year ago, they had candidates running for Parliament who had once posed for photographs wearing Nazi hats. That’s the reality. They are using the October 7 attacks as an opportunity to make people forget their past. But we can’t allow that to happen. You don’t erase your history by visiting Yad Vashem once. There’s political opportunism on both extremes.”

This inversion is not uniquely French. Across Europe and the United States, the rise of the “new right” has complicated old certainties. These movements, once instinctively anti-Semitic, now often find common cause with Israel against political Islam, seeing the Jewish state as a frontline defender of the West. At the same time, parts of the progressive left, once instinctively philo-Semitic, have recast Jews as symbols of privilege and Israel as a colonial oppressor.

If the Dreyfus Affair were reenacted today, who would rush to sign the 21st century’s “J’Accuse”? Would the professors, novelists, and editorialists of our time demand justice for the wrongfully accused Jewish captain? Or would they, as so many do now, see in his Jewishness not a marker of vulnerability but of culpability? Would the very intellectual classes who once rescued Dreyfus from oblivion now condemn him in the name of anti-colonial solidarity?

The question is not academic. For French Jews, the ground has already shifted. Jean-Yves Camus has noted a growing disillusionment with Macron’s centrism and a drift, however cautious, toward the right. Others, like councilwoman Shannon Seban, insist that the center remains the safest haven, warning against both extremes. But beneath these tactical debates lies a deeper unease: whether Jews can still trust the political currents that once sheltered them.

The Dreyfus Affair ended, after years of humiliation, with vindication. But the scar it left on France — on its institutions, on its Jews — has never fully healed. Today, the scar throbs again. Desecrated synagogues, online incitement, and street protests against “Zionists” form a pattern too familiar to dismiss. Thousands of Jews have already emigrated to Israel since 2023; thousands more weigh the decision daily.

If history teaches anything, it is that political alliances are never fixed. The left that once defended Jews may now turn against them; the right that once persecuted them may now extend a conditional embrace. What remains constant is the Jewish question itself, endlessly refracted through the anxieties of the societies in which Jews live.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 1079)

Oops! We could not locate your form.