It’s 9 a.m. — Do You Know Where Your Bochur Is?

| May 16, 2023It is a puzzle how these boys made it as far as the year in Eretz Israel without their learning difficulties being detected

Heshy (all names have been changed), a 21-year-old bochur from “one of the best yeshivos in America,” had come to learn in “one of the best yeshivos in Eretz Yisrael.” He began the first two weeks of the zeman with gusto; he found good chavrusas and kept good attendance at sedorim and shiur. However, as the zeman moved along, Heshy began waking up late, and his bedtime gradually slipped toward the wee hours of the morning. By the end of the first month, Heshy had lost his morning chavrusa as he often began his day in the afternoon.

Asher, an 18-year-old boy who came to Eretz Yisrael for shanah alef, was amicable and always smiling but never quite productive. At the year’s end, Asher found himself far from his intended goal. Unlike Heshy, who had gone almost unnoticed, Asher had a rosh yeshivah who was very involved with him throughout the year, speaking with him constantly, prodding and encouraging him to “live up to his potential.” Asher’s parents provided extra funding for a kollel man to get him up on time and inspire him during morning seder, unfortunately to no avail. When Asher did get up, rather than going to the beis medrash, he would visit all sorts of other locations.

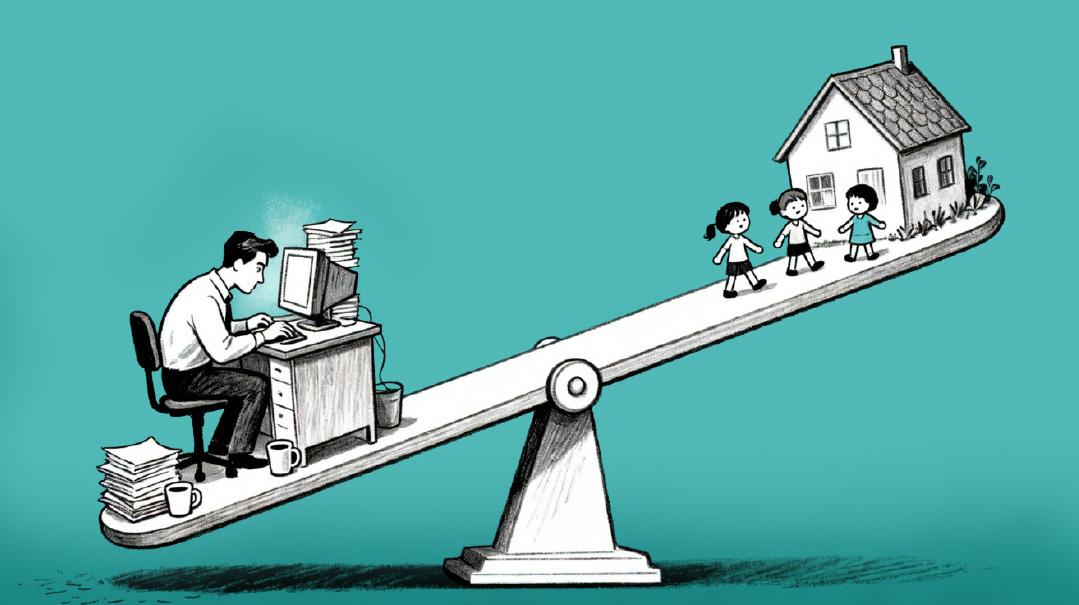

Eretz Yisrael is a land of golden opportunity for boys who want to grow in their Torah learning. For many, it’s the last stop before starting shidduchim; for others it’s a stepping stone toward a more meaningful Torah life. However, there is also a small but significant number of boys who fit the descriptions of Heshy and Asher. Truth be told, the story of their frustration begins much earlier in their lives.

Boys like Heshy and Asher struggle throughout their schooling years, often due to very real learning difficulties that go undiagnosed and untreated. Those challenges often lead to behavioral problems that are misidentified as mental health issues. And although these issues remain unresolved, they join their friends to come learn in Eretz Yisrael. It’s as if there’s an unspoken wish on the part of the parents, the rebbeim, and, obviously, the bochurim themselves, that they will finally find hatzlachah in the Holy Land. Yet for all their goodwill, they soon experience the sad, familiar story.

When we consider all the frustration they experienced in their formative years, we should be amazed at the unceasing resolve these bochurim demonstrate. Think of it: years of sitting in a classroom, giving their all in their studies and being exasperated at best, clashing with school staff and parents at worst.

Generally speaking, these boys experience one of two scenarios in their primary schooling. There are those who, due to their difficulties with following the lesson, keep to themselves and sit quietly in class, waiting for the bell to ring. Regrettably, they may gradually shut down with friends and family as well. Then there are those who act out, disrupt class, and often get into confrontations with their rebbeim.

In either case, when these talmidim advance to high school or mesivta, their already damaged self-esteem takes an additional beating. Should the talmid manage to use pull to get into a “top name” mesivta, his low performance and functionality are almost guaranteed to surface again. On the other hand, if he can only get accepted to a “place for weaker boys,” he will feel labeled as a failure.

BY the time our bochur gets to Eretz Yisrael, his functionality, like his self-esteem, is extremely low. Typically, he begins the zeman on a high note. This “fresh start” will bring him and his parents hope that “avira d’ara,” the kedushah of the Land, will infuse him with the passion for success that he so desperately desires. Sadly, a couple of weeks in, the momentum slowly fades and the painful nonfunctional style returns. Where is our bochur supposed to go from here?

Many times, he is sent to therapy — which is where I would encounter him. But I’ve found all too often that his dysfunction is not rooted in mental health issues, but in something that has until now been overlooked — an unnoticed or untreated learning difficulty that has plagued him for years.

Before Heshy began therapy, he self-diagnosed himself with “burnout,” based on materials he had read that “described his symptoms perfectly.” However, in his initial interview, it was clear to the therapist that his burnout had never been preceded by a “burn-in.” Heshy had never really tasted success in his studies throughout his yeshivah years.

In Asher’s case, his history of failure actually led to him to seek prescribed medication for what he believed was clinical depression. He had gotten as far as setting up a doctor’s appointment for that purpose, but one of his rebbeim advised him to see me first. Once again, the intake revealed a completely different story. Already from the early grades, Asher had experienced difficulty concentrating in class because of ADHD. Unfortunately, he was never properly evaluated, and he began acting out in class. Because of his disruptions, many rebbeim would remove him from shiur, occasionally publicly embarrassing him in front of his classmates.

True hero that he was, Asher persisted, relying on the assurances he received that if he just kept trying, he’d see, “everything will work out.” It is no wonder that toward the end of his mesivta years, feelings of hopelessness set in, and his attendance began to wane. The psychiatrist who ultimately diagnosed the ADHD expressed it succinctly: “He’s not clinically depressed, he’s sad.”

I became acquainted with this issue around two decades ago while working with Yossi, a 20-year-old bochur who had just been thrown out of yet another yeshivah. His behavior was intolerable, his adherence to the rules was nonexistent. A dedicated rebbi who was close to Yossi and concerned about his Yiddishkeit asked me to meet with him.

Truth be told, based on his behavior and family history, I suspected a personality disorder and sent him for a psychiatric evaluation. The doctor correctly identified ADHD, and in literally a few weeks, Yossi entered a new yeshivah and became a rising star. He ultimately got married and is now building a beautiful mishpachah.

That was a significant moment in my involvement with bochurim. Although I had previously heard of ADHD, it had not been included in any of my extensive professional mental health training. In addition, as a rebbi of a post–high school beis medrash in Eretz Yisrael, I do not recall the topic coming up in any of the chinuch forums. For whatever reason, there has been almost no consideration at all given to bochurim who have ongoing learning difficulties.

For those working in chinuch in Eretz Yisrael with American bochurim 18 years and older, the “given” is that a boy who has made it this far and is still unproductive must be experiencing an emotional issue. And, much of the time, he is.

But Yossi’s behaviors were classic for ADHD combined with “a 20-year, going-through-school, undiagnosed ADHD personality.” Not the typical diagnosis found in the DSM.

Remarkably, Yossi’s behavior that had me suspect a disorder was actually an effect of his issues rather than the cause of them. This is to say, for years Yossi had difficulty understanding the information being taught in class. This led to mushrooming frustration. Subsequently, he found it hard to remain seated and quiet, and he began to act out and disrupt the class. As time went on, Yossi started to question his emotional health — but he was never properly diagnosed. In turn, he subconsciously began fulfilling the role that he was convinced was assigned to him.

I work with psychiatrists, experts in reading assessment, and expert speech therapists, and collectively, we see scores of boys every year who fit this description. It is a puzzle how these boys made it as far as the year in Eretz Israel without their learning difficulties being detected. But some of the boys had never been evaluated, and others had been, but their parents did not follow up.

Furthermore, ADHD is not the only such issue. Boruch was an 18-year-old boy from Chicago in his shanah alef. Although his rosh yeshivah and rebbeim were trying to help him, his functionality was extremely low. He woke up around 11 a.m. and sauntered out of bed. After a long breakfast and shower, he would enter the beis medrash and sit with his chavrusa for a few moments before going out for a “short break.”

Boruch was quite an intelligent bochur with a pleasant personality, and we were developing a nice rapport. During one session, I offered a comment that I hoped would be a positive expression of my belief in him.

“You know, Boruch, you have so much potential,” I said innocently.

His expression suddenly turned somber. “I hate hearing that!,” he almost shouted.

Boruch explained that throughout his life, he had constantly been told how much potential he had. But instead of hearing positivity, he felt the pressure of unfulfilled expectation others had of him. Indeed, he knew that he was intelligent and had much going for him. The burden of hearing how he was not fulfilling his true potential only increased his consternation. So what, in fact, was deterring him from reaching his goals?

An informal test of his reading skills showed that his speed was slow and choppy. Sure enough, a proper evaluation by a professional found that Boruch’s reading skills were below average. It was a watershed moment for Boruch; he realized that his lack of success was not his fault and that there was no reason for him to feel guilty any longer. As his reading improved, his self-confidence grew accordingly.

AS I shared these experiences with mechanchim and therapists, I noticed that many of us had been unaware of the educational component to these problems, leading me to write this article.

In so many cases, young men who really are very intelligent can turn their hopes of success into reality. It would be prudent for rebbeim and therapists to explore the learning styles of talmidim who present with symptoms similar to those described above.

And we must not overlook those talmidim who have protected their shame by cunningly evading detection as they go through the system. Indeed, many of these boys have proudly confessed to me their prowess in feigning comprehension! They have learned to nod their heads at just the right moment. Throwing in an occasional comment like, “Oh, I get it, Rashi is like the second pshat of the Rashba,” allows their weaknesses to fly under the radar. But a caring mechanech’s perceptive eye could easily discern their difficulty in comprehension.

Baruch Hashem, there is an array of qualified professionals who are trained to evaluate the various issues that need to be explored, such as basic reading skills, comprehension of the material, information processing, and concentration. These can all be identified in simple evaluations, which will lead to removing the obstacles and paving the way for true growth.

For those readers wondering why this article is focusing on the Eretz Yisrael “late in the game” years, the response is that this writer is looking at the hard facts on the ground. Regardless of how and why this could have happened, the reality is that it does happen. And it is incumbent upon all of us to do what we can to help these boys own their future.

The “landscape” of Eretz Yisrael has changed over the years, and while the freedom of being far away from home confers a fantastic opportunity to generate healthy maturity, arguably, all yeshivos would do a great service by raising their awareness of where their bochurim are holding. Experience has shown that, generally speaking, the greater the knowledge there is of a talmid’s performance inside the beis medrash — whether it be his attendance or his comprehension — the less need there is to be concerned about what he’s doing outside the beis medrash.

Likewise, parents know the educational experiences of their children. Many of the factors that may have deterred them from having their child evaluated, or actually follow up on the suggestions of an evaluation, are no longer relevant in Eretz Yisrael. This year offers a chance to encourage their son to explore new solutions.

We need to keep in mind that the earlier the intervention, the smoother the process. Frequently, when the difficulties are treated in the later years of yeshivah, the bochur’s self-esteem has been so battered that he will require additional support to heal his wounds and shame.

The positive news is that even at this stage, most of these issues can be resolved to allow our bochur a functional, happy life. With a little bit of awareness, we can end the pain of a young man who has suffered so much disappointment in his early years, and help transform him into the vibrant, dynamic bochur that he truly is, advancing steadily toward a bright, successful future.

Rabbi Nesanel Volvey Rand is a rebbi in Yerushayim and a certified therapist specializing in anxiety and depression.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 961)

Oops! We could not locate your form.