It Takes a Real Mentch to Tame a Surreal City

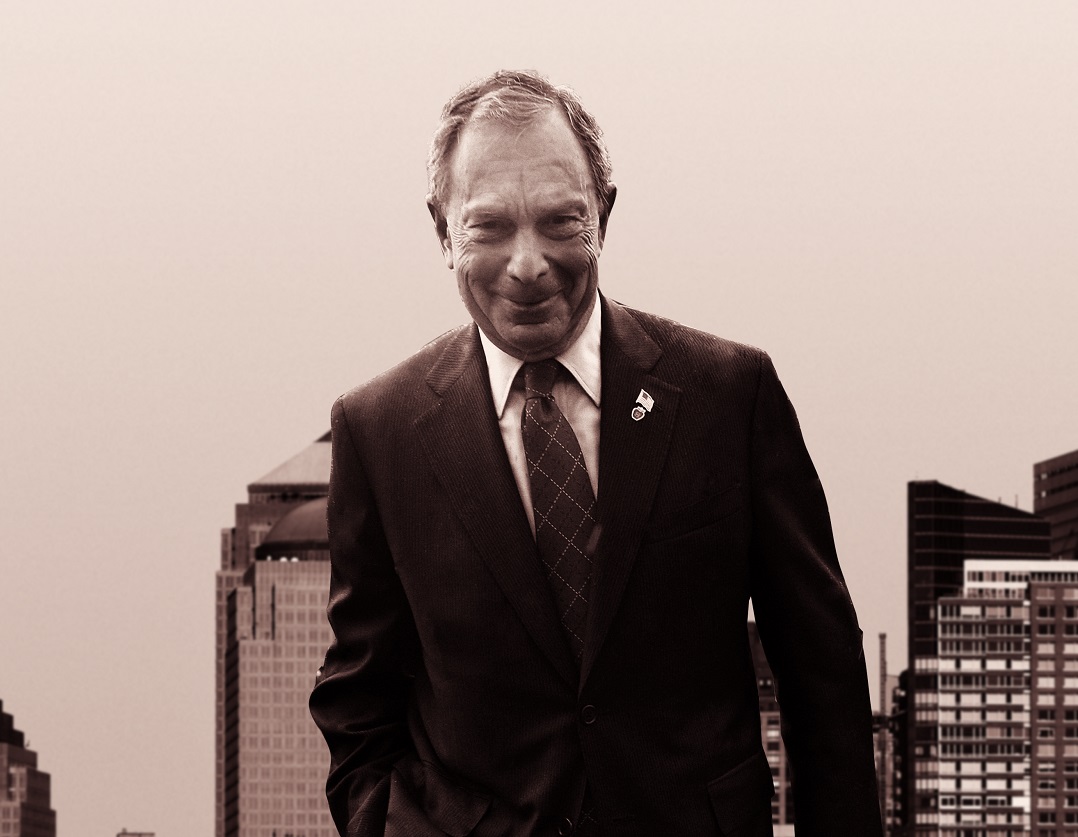

| October 28, 2009In an exclusive interview with Mishpacha Magazine, Michael Bloomberg, the incumbent mayor of New York, reflects upon his tenure as one of the city's most popular chief executives. A billionaire who's taken on New York City as a philanthropic gesture, Bloomberg shares a confident prognosis for the city's economy. In a nostalgic look at the past, he discusses his upbringing as a Jewish boy in an Irish and Italian neighborhood and lovingly reminisces about his biggest fan – his still-agile 100 year old mother. Most poignantly of all, he discusses what it means to be a Jewish mayor of the world's largest Jewish city

T

he exciting, boisterous city of New York is deep into a mayoral election campaign, but somehow seems unusually tranquil. Neither New York City’s ethnic diversity nor its unruly personality has unleashed any great anticipation or clamor during the various candidates’ mayoral bids. And New York is not just your average town. At issue is the position of the chief executive of the most populous city in the United States, which exerts a powerful influence over worldwide commerce, finance, culture, fashion, and entertainment. In addition to being the financial and cultural capital of the world, and — as host of the United Nations headquarters — an important center for international affairs, New York is also the metropolis with the largest Jewish population and most Jewish religious and cultural institutions in the world, outside of Israel. Yet neither the population at large, nor the Jewish communities in particular, have staged any animated political rallies, and no major policy debates have rocked any of the city’s five boroughs. Notwithstanding a two-term limit previously enacted in New York by public referendum, incumbent Mayor Michael (Mike) Bloomberg, who has prevailed in this Democratic stronghold as a Republican convert, and considered by many to be one of the most effective mayors in the city’s history, is seeking a third term for office, and only the diehard politicos appear to be paying much attention.

Despite the relative calm that seems to have mysteriously enveloped this energetically diversified city, there are still some New Yorkers bursting with verve who are trying to get their respective candidates elected. One of those animated young people who is not getting much rest these days is the spirited, twenty-four-year-old Mark Botnick. Mark is working for the Bloomberg campaign as the mayor’s liaison to the city’s various Jewish communities, and in this capacity is wholly engrossed not only in city politics but in internal Jewish affairs. Familiar with Yiddish and fluent in Hebrew, Botnick, who grew up in Riverdale, New York, knows a thing or two about our society’s makeup and concerns.

Mark Botnick may have majored in political science at Queens College before joining Mike Bloomberg’s campaign in 2005, but it’s his exceptional street-smarts that may be his greatest commodity these days. He knows which Jewish communities would welcome a political rally for his boss, and which communities would do better without, since one segment of the community does not necessarily hold in high regard the leadership and communal legitimacy of the other segment. Mark, however, takes it all in good humor; perhaps because he resides safely away from all the rancor, on the relatively serene Upper West Side of Manhattan.

The only thing that may be more animated than Mark himself in this mayoral election season is his restless BlackBerry. After an exchange of many e-mails and text messages, Mark invites me to meet the mayor at his campaign headquarters on the fifth floor of a West 40th Street skyscraper, off Avenue of the Americas in Manhattan.

The Jewish People have long ago been charged with a duty to maintain good relations with the government, and perhaps no one understands this need better than my friend Rabbi Moshe Indig, a highly regarded community activist. Being an early and strong supporter of Mike Bloomberg, Rabbi Indig enjoys a very close working relationship with the mayor’s Community Affairs Unit, which is headed by Assistant Commissioner Fred Kreizman and, prior to the election season, also by his colleague Mark Botnick. He was instrumental in helping arrange my unique private audience with the mayor, which has now been confirmed for 6 p.m. on the Wednesday following the Jewish holiday of Succos.

The Only Poll That Matters

I settle in to wait for my audience with the mayor in the slogan-plastered, windowless conference rooms at his bustling campaign headquarters, slightly unnerved by the photographer who seems to be aiming his large black camera at me. Though the mayor shows up about three-quarters of an hour late, Mr. Bloomberg has a surprising air of punctuality about him. Unusually erect for a sixty-seven-year-old, he walks briskly and with a definite sense of purpose. Michael Bloomberg appears professorial, but has an inviting and homey smile. There’s a lot to grin about when you are one of the wealthiest people on earth, I figure, especially when what you do on a day-to-day basis is not your source of income but merely a sport. Mike Bloomberg is not only a multibillionaire, but a generous one at that as well, and is considered to be one of America’s greatest philanthropists. He donated $205 million for charity in 2007 alone, making him the seventh-most-generous individual contributor to philanthropy in the United States for that year.

As he enters the room I remember that in a 2005 interview with the New York Times, Bloomberg made a revealing comment about his religious views and identity. “I believe in Judaism, I was raised a Jew, I’m happy to be one — or proud to be one,” he said. Then he paused and added: “I don’t know if that’s the right word. I don’t know why you should be proud of something. It doesn’t make you any better or worse. You are what you are.” Bloomberg displays a similar happiness and pride in our conversation tonight, as the unique spark that is somehow hidden in the Jewish soul seems to be very much present.

Bloomberg may be happy and proud this evening about many more things, not the least being his performance the night before in a televised debate with his political opponent — vying for his position as New York City’s chief executive — City Comptroller William Thompson Jr. The Democratic comptroller, trying to unseat the popular mayor, lobbed multiple attacks at him during their first debate, seeking to portray Bloomberg as opportunistic for past political moves, including changing his lifelong party registration from Democrat to Republican to avoid a crowded primary in 2001 and persuading the city council to extend the term-limits law last year so he could run again. Yet most political pundits seemed to have agreed that the mayor held his own, and gave as good as he got, while making a convincing argument that for the sake of the populace and the welfare of the city, he should be reelected.

The mayor apologizes for keeping me waiting, as he greets me warmly. When I tell him that he did great the night before, his instantaneous good-humored response is: “You and my mother think so.” Indeed, the mayor announced earlier that day while on the campaign trail that his hundred-year-old mom had rated his performance A ++.

Regardless of his performance, I reassure the mayor, it would be hard for his opponent to overtake the seventeen point lead that the mayor is currently enjoying in the polls. “I’ll let you know on November 3rd,” he rejoins. “In the end, that’s the only poll that matters. It all depends on who goes out to vote. The Orthodox community says it will vote for me. But if it says, ‘Oh, he’s seventeen points ahead,’ then things may turn out quite differently. I may be ahead now, but in theory I could still lose. Nothing can be taken for granted. Notwithstanding all our election drive efforts, including throwing pebbles at your window at three in the morning to wake you up to go out to vote, everything depends on turnout.”

I tell the mayor that the sole problem that I foresee is the fact that he only has one mother to vote for him. “I’ve got even a bigger problem,” he responds. “My mother resides in Boston, and she cannot vote at all in New York.”

Mr. Bloomberg, trying to dispel any notions that one can deceive him as to who actually voted for him, shares an amusing anecdote. “A few years ago a restaurateur and her husband were going on and on how they voted for me in 2001, and took friends to the polls, and that sort of thing. I have an Irish assistant, Shea Fink, who’s just dynamite; she went to check. Neither of these people were even registered voters. Later, in 2005, she made sure that they actually voted for me.”

I joke that Mark Botnick is already planning the mayor’s victory celebration. “Well, let me put this all in context for you. I will be on the southern coast of Spain practicing my Spanish and my golf the next day, if I lose. He will be unemployed.”

Different Times

“You mentioned Boston, Mr. Mayor,” I say now a bit more seriously. “Is that where you come from?”

“I grew up in Medford, Massachusetts, a suburban city not far from Boston, where the guy who sold my parents a house in 1946 when I was four years old, didn’t want to bring Jews into the neighborhood. So he sold the house to my father’s Irish lawyer, who subsequently resold the house to our family. That was a different time. Jews were not allowed to live everywhere so we had to move covertly into the area. We were not exactly pioneers in that neighborhood, though, and we never had any problems there. There was a shul in the neighborhood, where I attended Hebrew Day School in a big old Victorian house painted yellow. I can picture it now. It was then known as the Medford Jewish Community Center, which is not a temple that you would probably go to. It is a Conservative shul, that I actually recently redid for them. It is now named the William and Charlotte Bloomberg Jewish Community Center. But we were then one of a few.”

Bloomberg the super-achiever is essentially a self-made billionaire and successful politician who hails from a modest, but more religious, upbringing. “My father was a bookkeeper for a dairy company from Chelsea, Massachusetts. His father was a rabbi, who I’m sure made most of his money from tutoring kids for their bar mitzvah. He came over here at age six, maybe from Lithuania. Nobody is really certain where he came from. It’s funny; when I was in college in Baltimore he asked me to look up in the phone book if there were any Bloombergs and call them and see if anyone might be his brother. He said that he remembered that he had an older brother who got out of Eastern Europe, wherever he came from, earlier. He said, ‘I can never find him in Boston, and Baltimore-Boston might have sounded the same.’ So I called two or three people and they wanted to know what I was selling, so I stopped calling. Before he died he told me that maybe his original name wasn’t even Bloomberg. Well, he was only six years old when he came here.

“My mother’s mother was born about 1860, on Mott Street, on the Lower East Side of Manhattan. Now it’s a Chinese neighborhood, but it was Jewish back then. The first time I came to New York was in April of 1942, when I was three months old. We came down to visit my father’s sister, with her husband and son. They lived in the Washington Heights section of Manhattan, and it was an all Jewish neighborhood then.”

Jews are indeed a migrant people. That historic tendency did not change much, even on American shores; after settling in one neighborhood a few years later they would leave and move to another. “It is fascinating,” the mayor reflects. “You go to these churches, temples, and mosques, and you go to some of these little black churches, and you look at the stained glass windows and you see little Stars of David.”

During the other night’s debate, Bloomberg replied to one of the questions in broken Spanish as many members of the audience started chuckling. I ask the mayor whether his Yiddish is somewhat better.

“I’m still trying to learn the Yiddish language. My parents would speak Yiddish when they didn’t want my sister and me to know what they were talking about. They were fluent in the language enough to keep us guessing what they were saying.”

“I heard that the mayor’s mother’s still keeps a kosher kitchen,” I say.

“Oh, sure she does. My younger sister, who lives in New York, keeps kosher as well, while two of her daughters, incidentally, speak fluent Hebrew. This year, because of my mother’s advanced age, she couldn’t manage to bring the Pesach dishes up from the basement. I had the rabbi say from the bimah this past Yom Kippur that when you are elderly and frail you should not be fasting. Two years ago she fasted and she passed out in the temple. Well, she’s a hundred years old. She’s still quite sharp, though she doesn’t hear that well and is a little bit forgetful. I don’t either remember what I did this morning. So we’re not that different.”

It is apparent that campaigning in a city with a large Jewish population has made the mayor think about his Judaism and has turned this pragmatic businessman and politician into somewhat of a religious thinker. “This past Simchas Torah,” the mayor reminisces, “I went to three different Bukharian shuls. It is fascinating, the differences within Judaism between one place and the other. An outsider views it all as one. When Christians have asked me about Judaism versus Catholicism, I tell them that there is no one person who speaks for all Jews. And I happen to think that is one of Judaism’s strengths. And I never believe that each community is as homogeneous as they say they are. One of the nice things about Judaism and the Talmud is that you can have debates about certain things. Judaism teaches us that G-d expects us to take care of each other.”

Being charitable is indeed a Jewish trait, and I wonder now aloud whether Michael Bloomberg views his mayoralty as a form of philanthropy and a way to take care of others. After enjoying a successful Wall Street career and building one of the great media companies of the day, rather unbelievably for a billionaire, Bloomberg aspired to be the mayor of a demanding and complicated city, and has yet succeeded at that. He has risen above the sordid politics of New York to become one of the city’s most popular mayors. He has driven crime down, rebuilt neighborhoods, kept the streets clean, overhauled the schools, and has kept the peace between New York’s various ethnic groups. New Yorkers are reputedly even living longer than they used to.

But Bloomberg is quick to downplay the glory of his position. “When you get up in the morning and they blast you in the papers,” he tells me, “I don’t need that at my age or at my wealth. I’m certainly not doing it for the money. I’m getting a dollar for this a year, and it’s actually ninety-three cents after they take out Social Security. I don’t even cash these checks, but have them all framed. I’m doing this because I’m trying to leave a better world for my kids. I think there is a selfish component, and I always thought there is a selfish component in all philanthropy; you want to be able to think to yourself that you’re doing something good. There is a sense of satisfaction in doing that. And I would like to guide the city through some tough times and be able to look back and say that I left the city better. And if you said, ‘Well, could anybody else do it?’ I would like people to say that he was one of the best mayors. I don’t think there could be a best mayor, because everybody has different challenges and different resources to deal with them, and you never have two mayors at the same time. It’s not like a science, where you could repeat the experiment.”

Climbing Out of the Recession

Whether he is the best mayor or one of the best, Bloomberg is seen by many political observers to be a lasting winner. He has succeeded in bringing nonpartisan leadership into the messy world of New York politics, and has been given high marks for maintaining the city’s finances during one of the most savage of recessions. I mention his financial expertise as I ask him to share with me his views about the economy.

“I’m only an expert on New York’s economy,” he says with apparent understatement, “and it is doing better than forecast. When I go to restaurants — there are twenty thousand restaurants and I go to a different restaurant almost every day throughout the boroughs — every restaurateur will tell you that business is better. Stores, real estate brokers, banks will all tell you that business is a little better. If your question is: ‘How long will it take to get back to the craziness we had three years ago?’ the answer is it will take a very long time. But we eventually will, because the history of financial markets is that you up-up slowly with derivative increases, you start going further and further, and then boom. We have been doing this since the tulip days in Holland. This shouldn’t surprise anybody. Wall Street is actually making a lot of money; it is doing very well. If you look at their revenue versus expenses, those numbers are good. I can see that in my own companies’ business, so that’s good.

“I don’t think we are going to go back to the craziness for a long time. Three years ago people were joking that you could get no-covenant loans that you never have to pay back. People were buying companies through the market believing that they could run the company better than the guys who founded it and have been running it for twenty years. So why is the guy selling it? Because he doesn’t think it’s worth that. So what are you, smarter than the seller?

“So, I’m optimistic. But I’m not optimistic in the sense that we are going to get back right where we were. If I were a developer I would put a shovel in the ground now to have a building ready in five years, particularly commercial buildings, because all these companies are not leaving New York. When they downsize, they concentrate in New York, actually.

“There are two components to your question. The one I’ve been answering is about the economy. What you didn’t ask me is about the economics of the city government. That’s very different. Our tax revenue will be five billion dollars less than last year, because Wall Street is not going to pay any taxes no matter how much money they make for four, five years. And that hurts us. That means we are going to have to find ways to do more with less. You can’t raise taxes; you’ll drive small businesses out. The State has already raised its taxes. Tomorrow the governor is going to announce big proposal budget cuts. But he doesn’t have any say, so let’s see what happens. But at some point they are going to have to raise taxes, cut expenses, and they will do it on the backs of New York City.”

“Does New York City and the mayor of New York City,” I ask, “have any effect and influence on the global economy, or do we merely ride along with what the rest of the world does?”

“It depends on the market. The financial capital of the world is and will be New York City, and New York City will come out of this strong. To be a financial capital you have to be English speaking, because that is the business language of the world, and you have to be family friendly, because you can’t get your best traders and salesmen and managers to move there if they can’t bring their families. You know, Beijing is exciting, but most American families don’t want to go live there. You can’t speak the language, you can’t get around, the food is different, you can’t find your local shul. Whatever it is, it is harder to do. London is somewhat better. You can live, but the traffic is terrible, and crime is skyrocketing in London, and it still is very expensive. Compared to London, New York will do well. Neither London, Tokyo, nor Beijing will take us away.

“The good numbers are: tourism is down a couple of percent here, and double digits elsewhere in the country. Hotel occupancy here is better than 80 percent, it is less than 50 percent in the rest of the country. If you talk to the labor unions they will tell you that 20 percent of their people here are out of work, while it is 50 percent in other cities. So we are doing better. Some of the big economies like China are going bang-busters. I don’t know whether they just make up their numbers or if they’re indeed real. But I wouldn’t invest in China because I don’t believe in their method of bookkeeping. If you think Bernie Madoff was good at doctoring his books, well …

“I actually knew Bernie, I knew him very well. His company and Salomon Brothers, where I was employed, worked together on these market regulations that the FCC put together. The last person in the world you would think was a crook was him. That’s one of the reasons he was so successful.

“My theory is that Bernie Madoff followed the rule of running a good party. There’s an old joke: if you want to run a good party, get a room too small for the crowd. I don’t care how small a crowd it is. If it’s two people, get a room that holds one. If it’s ten people, get a room that holds five. And Bernie did that. He had a room too small, and if you wanted to give him money, he said, ‘I’m sorry but I can’t take your money.’ Then you started begging him to take it and you never thought about what he was doing, only about the fact that he didn’t want to take your money. I have a friend in London who is very wealthy and is interested in secular Judaism, which I could never figure out what that means; he lost an enormous amount of money with him. Hadassah lost a lot of money with Bernie as well. I tried to make up some of their losses, but I can’t go make up every penny.

“I once said that the only one who ever committed a bigger Ponzi scheme than Bernie Madoff is Social Security. Social Security is the ultimate Ponzi scheme.”

The mayor is suddenly distracted by a text message and says that he will have to leave shortly to go to Brooklyn. I offer to drive him there since I’m headed to Brooklyn anyway and he says: “Better yet, you’re paying for me to go. You’re paying for the SUV that guzzles gas with the detectives outside. Thank you very much. It is the ultimate in public transportation.”

International Hub

For some arcane reason, New York City mayors always seem to be getting involved in international affairs, where they don’t seem to belong. While New York City indeed hosts the United Nations, 192 permanent missions to the United Nations, and 110 consulates, that does not necessarily mean that the mayor’s business includes foreign affairs. Tonight I have the opportunity to ask the chief executive of New York City a question that has always been intriguing to me: “Does New York City have a foreign policy?”

“Yes, much to the State Department’s annoyance,” Bloomberg tells me. “I think you can characterize our foreign policy as that I believe we should be open to everyone. When the Taiwanese government comes here I will welcome them. If the Palestinian, or the Iranian, or the Korean government comes here, we should provide protection for them. You cannot have the United Nations and not let everybody here. I don’t agree with the United Nations on most things, but I’d rather have people talking than not talking. And if they’re going to talk, I’d rather have them do it here where they spend money. It’s a very big part of our economy. Take a look at all the embassies and consulates.

“Thanks to my sister, Marjorie B. Tiven, who is the New York City commissioner for the United Nations, we are getting the governments to pay for their diplomats’ parking tickets. I got a call from Colin Powell when he was secretary of state saying ‘I’ll do anything you want, just get your sister to stop calling. Please, she’s got to stop, she’s going to drive me crazy.’ Today every embassy and consulate pays their tickets. There’s a billion dollars worth of tickets left over from Cuba. They’re not going to pay that. What’s more, many of those tickets were issued within a few minutes of each other, and no court will enforce that.”

In a recent editorial endorsing Bloomberg’s bid for reelection, the Jerusalem Post wrote: “New York City Mayor Michael Bloomberg has proven himself to be the most steadfast of supporters of Israel, repeatedly going far beyond the call of duty to underline his own, and his city’s, solidarity with our country when that solidarity has been needed the most.” Few would disagree with the assessment that Bloomberg emphatically supports the Jewish State, and that his office has been exceptionally sympathetic to Israel.

“I annoyed the Muslim community, whom I have an obligation to take care of as well, when I went to Israel as the rockets were hitting Ashkelon and Sderot. I had breakfast with a bunch of Arab leaders before I went and when I got back. I said: ‘Look, you got to understand, number one, any mayor of New York City is going to be Zionist. Period. Number two, I happen to be a Jew who feels very strongly that that is my culture, that’s my ancestors, and that’s the freedom for the world. If Israel were to fall it would be a very sad thing for all of us. So you got to understand, I’m sympathetic that you have family in Gaza and they’re getting killed, but it’s Hamas in the end who’s responsible.

“I’m not reticent about speaking out. Hillary Clinton certainly knows where I stand. The president the same thing. You know I spent some time with Netanyahu. Bibi and I have been friends for fifteen years. I have an office in Jerusalem. I have given Hadassah two wings for the hospital in honor of my mother. I’m redoing a building in memory of my father for Magen David Adom, for their ambulance corps.

“I’ll tell you a quick story about my father, and then I got to go. In the early 1950s there was a business convention in Miami Beach, Florida, and my father was invited to attend. So my mother goes to the library and gets books on what you do, how you dress, what you say at conventions, what happens at conventions. My father gets to the desk in Miami Beach to check in, and the clerk behind the desk says, ‘Bloomberg, Bloomberg, is that Jewish?’ My father said: ‘Yes.’ The clerk said: ‘We don’t take Jews.’ Somebody made a fuss, and he got in. But when he got back, we discussed discrimination around the table. I remember all that.”

Not Politics as Usual

In 2008, Mayor Bloomberg appeared to have been flirting with the idea to run for the White House as a third-party candidate. As he is seeking a third term as mayor, I ask him if he would pursue a higher office on a national level with the aspiration to be the first Jewish president of the United States.

“No. I used to think that I’m too liberal for the Conservatives and too conservative for the Liberals. Now I’ve convinced myself that I’m too conservative for the Conservatives. I don’t think we should be spending money we don’t have. And I’m too liberal for the Liberals, I actually believe in some of these things.”

“Is that the reason you didn’t run in 2008,” I ask.

“It’s very flattering that people thought I could, but a third-party candidate can never win the presidency in this country. There are too many people who automatically vote along party lines. If 20 percent vote Democratic no matter what, and if 20 percent vote Republican no matter what, in a three-way race, you know what a percentage of the 60 percent in the middle you got to get in order to win?”

“And as a main party candidate would you consider running?”

“One of the reasons why mayors never go on to higher office, is you have to explicitly take positions. You can’t do what John Kerry did; he voted for the war but not to fund it. And for every explicit position, you lose half the electorate. By the time you have five explicit positions you got one sixteenth of the vote. The next one is me and my mother; I’m not sure about her.”

President Obama, with whom the mayor has had a complicated political relationship, endorsed his Democratic rival, Bill Thompson, for mayor. Yet, as the New York Times pointed out, “it was the most lukewarm and indirect of endorsements, delivered in the conditional tense, and coming from a presidential spokesman, no less.” Indeed, as the spokesman was endorsing Thompson without even mentioning his name, he singled out Michael R. Bloomberg by name for praise. When I ask the mayor to comment on Obama’s lukewarm endorsement of his opponent, he delivers a short assessment of the Obama administration.

“Regardless what he does, I’m going to work with him. We need him to be a good president. And I hope he is. It’s not easy. I’m sympathetic to him. He gets beaten up every day. He can’t just issue orders; he has to convince other people. He’s having tough times. But that’s the job.”

“And what do you think of his winning the Nobel peace prize?” I ask.

“You know, it was a surprise to him, and he handled it as well as he could. He said this is for potential and for everybody in America. And if it does any good, it is an impetus for him to work harder for peace. What else are you going to say? Would he have given it to himself? Probably not. But that’s okay. I think there are a lot of other people who would like to win. Let’s see when he finishes four or eight years, maybe he will really do more for peace than anyone else. That would be great.”

When I tell Mr. Bloomberg that what I find fascinating about his tenure as mayor is that he’s a pragmatist and it’s not politics as usual, he responds with self-deprecating humor. “What are they going to do to me? I’m sixty-seven years old. But my genes are okay. My father died at fifty-five, but he had rheumatic fever. His parents lived well into their nineties. You got my mother; my grandmother lived into her late nineties.”

With that the mayor ends our conversation and thanks me while walking with me to the office wall for some photo shoots. In stark contrast to his public image, I found Mr. Bloomberg to be warm, candid, and talkative, and he continues to talk as we pose for the camera, saying: “I’m a lucky guy. It’s a wonderful country. We Jews should just remember that around the world you are not as safe as you are here.”

Though the mayor is now rushing, I ask him one final question: “What does it mean to you to be the chief executive of a city with one of the world’s largest Jewish populations?”

“Well, I am mayor of the biggest Jewish city in the world, and it means that we have more of an obligation than any other city to protect everybody else because we know what happens with intolerance; we have experienced it for thousands of years. In particular, we should reach out to those Muslims who are not terrorists and who want to live in peace, because, as my father said to me, a discrimination against one is a discrimination against everybody.

“There’s a poem in the United States Holocaust Museum thatMartin Niemoller wrote in 1945, that goes:

“‘First they came for the Communists,

and I didn’t speak up,

because I wasn’t a Communist.

Then they came for the Jews,

and I didn’t speak up,

because I wasn’t a Jew.

Then they came for the Catholics,

and I didn’t speak up,

because I was a Protestant.

Then they came for me,

and by that time there was no one

left to speak up for me.’”

(Originally featured in Mishpacha Issue 281)

Oops! We could not locate your form.