Industrial Pogrom

| March 25, 2025The Triangle Shirtwaist Factory blaze claimed the lives of 146 workers, mostly young Jewish women

Title: Industrial Pogrom

Location: New York City

Document: The Forward

Time: March 1911

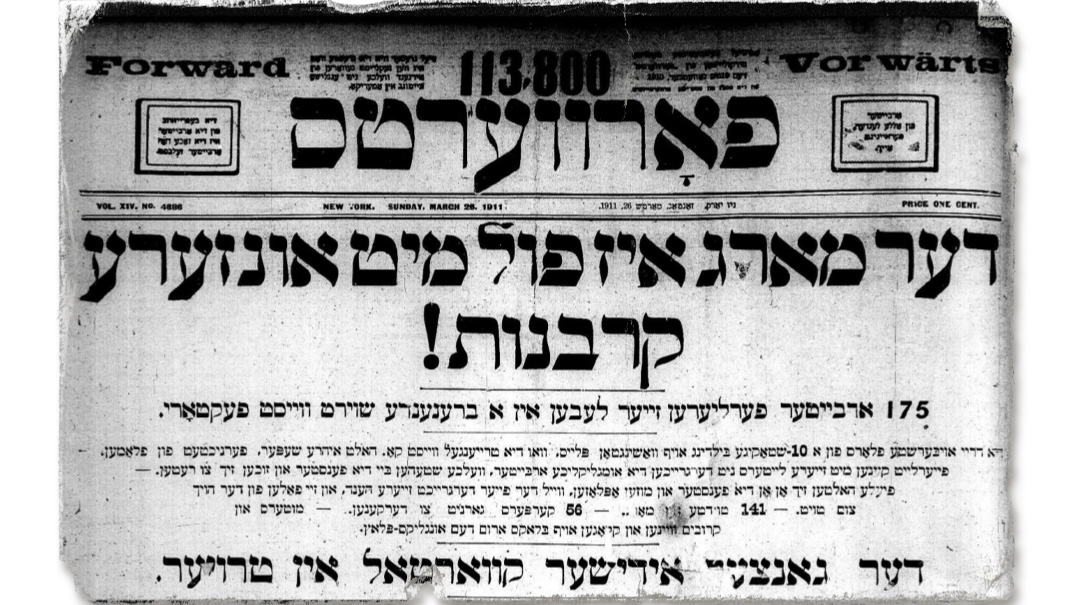

One hundred forty-six workers had perished in the fire, all but 21 of them girls, the great majority of them Jewish. “The Morgue Is Full of Our Dead,” said the banner headline in a special edition of the Forward put out that same evening. “The Whole Jewish Quarter Is in Mourning.”

All through that night and into the next day, there were terrible scenes of families identifying the victims. Each day thereafter, the Forward printed groups of pictures of those who had been identified, with the words: “Tears fall around these pictures.”

The pages of the paper were filled with tragic accounts, under such headings as: “Funerals instead of weddings”; in one case, a picture of a bride and groom bore the caption: “Becky Kessler, the bride, was burnt to death.”

Seven of the bodies were never identified. A mass funeral was held for the victims on April 5. By this time, the spirit of organized labor had been aroused, and the funeral was turned into a demonstration of workers’ solidarity.

“Come and pay your last respects to our dead,” the Forward urged that morning, “every union man with his trade, with his union.”

It was raining, but a crowd of perhaps a hundred thousand persons marched in silence through the streets of the Lower East Side to commemorate the dead.

—Ronald Sanders, The Downtown Jews

ON Saturday, March 25, 1911, a devastating fire erupted at the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory, a garment workshop situated on the 8th through the 10th floors of the Asch Building near Washington Square in New York City. The blaze claimed the lives of 146 workers, mostly young Jewish women. The horrific tragedy marked a turning point in American labor history, and illustrates the struggles of Jewish immigrants in early 20th-century America, and their resilience.

At the turn of the 20th century, New York City was a beacon for millions of Jewish immigrants, primarily from Eastern Europe. Seeking refuge from poverty, pogroms, and political unrest, they arrived on American shores with the hope of a better life. Yet many found themselves living in overcrowded tenements, struggling to make ends meet in the fast-growing metropolis.

Jewish women would become an integral part of New York’s garment industry. As the city’s garment sector boomed, these women filled the factories, sewing shirts, blouses, and other clothing items under difficult and unsafe conditions. The Triangle Shirtwaist Factory, located on the upper floors of the Asch Building, was no different. It employed more than 600 workers, many of whom were young Jewish women in their teens or early twenties. These women, often recent immigrants, worked long hours for low wages, producing the popular shirtwaists that were in demand in the early 1900s.

Although the industry was flourishing, these workers faced a harsh reality. They worked grueling shifts, under dangerous conditions, in an oppressive environment. Factory owners, seeking to maximize profits, took little concern for the workers’ well-being, providing only the most basic amenities. It was a system that exploited young Jewish women needing to support their families, many of whom had little choice.

When the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire broke out, it spread rapidly due to the factory’s nonexistent safety measures. Flammable materials, cramped working conditions, and a complete lack of any fire escapes made the factory a death trap. The doors to the stairs were locked. Some were able to break the doors open and make it down the stairwell, while others got to the elevator on the other side of the floor. The rest were trapped. The flash fire consumed everything in its path in less than ten minutes. In those terrifying moments, some jumped to their deaths from the windows, while others perished in the blaze.

When Jews had historically confronted pogroms, expulsions, blood libels, and similar tragedies, the victims were considered holy martyrs and their memories cherished. Although there was no shortage of blatant anti-Semitism in the United States at the time, it generally remained in the realm of rhetoric, and it certainly never resulted in the type of violent mass murder Jews had experienced in Czarist Russia.

In that context, it is fascinating to note that the Lower East Side Jewish community treated the victims of the Triangle Shirtwaist Fire as if they had died in an industrial pogrom. The industrial disaster was seen not only as a tragedy attributable to negligence, but also as the manifestation of an oppressive reality that was the direct human cause of the victims’ demise. Recent immigrants, struggling to earn livelihoods, subject to deadly working conditions, fell victim not to Old World anti-Semitic thugs, but to New World industrial overlords; and not on account of their Jewishness, but of their immigrant status as Yiddish-speaking foreigners.

A trilingual sign calling for mass participation in the funeral of the fire victims illustrates this quite poignantly. In English and Italian, the public proclamations simply state: “Fellow workers! Join in rendering a last sad tribute of sympathy and affection for the victims of the Triangle Fire. The funeral procession will take place Wednesday, April 5th, at 1 pm. Watch the newspapers for the line of the march.”

In contrast, the Yiddish section of that same sign was a heartrending and impassioned cry befitting any pogrom back in the alte heim. “To the levayah, brothers and sisters! The levayah of the holy korbanos of the Triangle Fire will take place… No one should remain in your shops! Lock them all up! Draw forth your sympathy and deep regret for this terrible loss… With torn hearts let us escort our dear brethren to their final resting place… To the levayah of the holy korbanos — all of our brothers and sisters must come!”

Jewish organizations rallied to support the victims’ families, raising funds for funeral expenses and assisting with the aftermath. Public hespedim were held in shuls across the city. The fire galvanized the labor movement, and Jewish labor leaders such as Rose Schneiderman helped push for reforms in workplace safety and workers’ rights.

Shabbos Tragedy

To compound the sadness for the immigrant generation, the fire had broken out on Shabbos afternoon. Most Jewish immigrants had no desire to work on Shabbos and did so with great reluctance and deep pain, often accompanied by shame, feeling that this was the only way for them to survive and support their families in the new country. The immigrants’ confrontation with the New World would include both physical and spiritual challenges.

Not Dying in Vain

The Triangle Shirtwaist Fire attracted wider public attention as well. Public outrage over the preventable loss of life prompted the New York state government to launch investigations into factory conditions. The fire became a key moment in the history of labor reform, leading to new laws that improved working conditions across the United States.

Among the most significant reforms were new building safety codes, including the installation of mandatory fire escapes and sprinklers, and the prohibition of locked doors during work hours. Additionally, the fire spurred the creation of workers’ compensation laws and the eventual establishment of the New York Factory Investigating Commission, which would continue to advocate for better labor practices. The Jewish community’s involvement in these reforms helped ensure a safer, fairer working environment for all, particularly for immigrant women.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 1055)

Oops! We could not locate your form.