In the Guise of a Madman

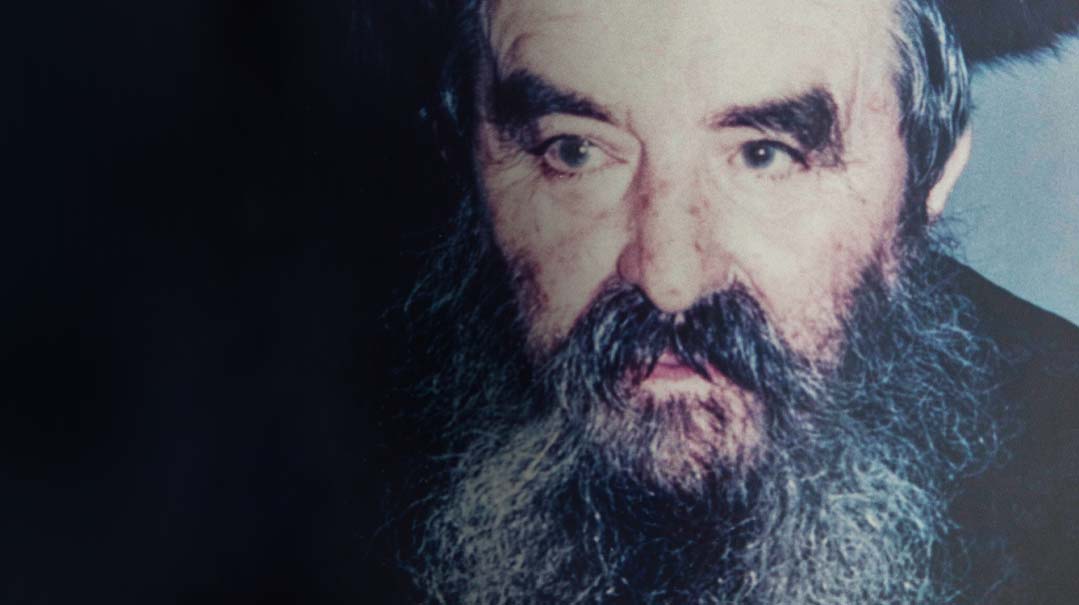

The many broken, down-and-out visitors to Rav Avraham Yechiel Fisch’s home in Tel Aviv were looking for some measure of salvation — and they knew the blessings would be hidden in the cryptic ramblings of this hidden tzaddik.

He called himself “the king of the crazies.” He lived in a rundown apartment building in the south of Tel Aviv, dressed in hand-me-downs of the deceased, spoke in cryptic, disjointed sentences, and worked as a common construction laborer. He always seemed surprised, even a bit angry, when people would come to seek his blessing and his advice.

“Go to Bnei Brak or Yerushalayim,” he would yell, trying to chase them away. “The gedolei hador are there. What do you want from a crazy person like me? Leave me in peace.”

The more tenacious among them were begrudgingly showered with good wishes cloaked in uncomplimentary epithets; others were indeed convinced that they had arrived at the wrong address.

Rav Avraham Yechiel Fisch ztz”l might have called himself “the king of the crazies,” but through his actions and promises, sick people were healed, childless couples were blessed with children, older singles found their zivugim, and Jews who had lost their jobs found ways to make an honorable living. He would ramble on, and couched between words that seemed to make no sense he would utter “A child will come,” to a barren woman, or “An angel will come and hide the file,” to someone facing felony charges.

Although 15 years have passed since the death of this hidden tzaddik, the lives he influenced and the salvations he accessed still reverberate throughout Israel and beyond, although no one ever really learned his secret, even those closest to him.

How many times did I, too, visit the house at Rechov Kalisher 32, making my way through the throngs of people lining the hallway outside his door — chassidim together with traditional Sephardim, people who had to borrow a yarmulke and vagrants pulling themselves from the sidewalks of the Tel Aviv slums. I merited my own salvations and fulfilled prophecies, but take a random survey of Israelis and many of them, too, will concur. Rav Fisch didn’t discriminate.

Sunset Strategy

At the entrance to the rundown building on Rechov Kalisher in Tel Aviv stood an avreich from Bnei Brak who had fallen on hard times and lost his apartment. He thought he was finished — where would his growing family live, even temporarily? He came to Rav Fisch on the advice of a good friend. He wasn’t asking for a handout, Heaven forbid; that would be too shameful. All he wanted was a brachah and some advice.

“Yungerman,” Reb Avraham thundered at him, “I will give you a sizable loan, enough to put down to buy an apartment. You must pay it back within the year; every three months, you will pay me a quarter of the sum. The payments will be due on Rosh Chodesh. Woe be to you if you come after the sun sets on Rosh Chodesh.”

The avreich wasn’t accustomed to hearing such sharp words, and Rabbi Fisch had some even sharper things to say as well. But the avreich took the bundle of bills and left, relief washing over him.

He managed to bring the first payment on time, but he was late with the second; he arrived after dark, and Rav Fisch was enraged. “I told you not to come after sunset!” The young man was perplexed; he had barely managed to come up with the sum that he had to pay back, and what difference did it make to this temperamental man if he came before or after sunset? Was there some mitzvah here that was limited to a specific time?

“Get out of here!” Reb Avraham shouted. “Don’t come back, and don’t bring me any more money. You don’t know how to be on time!”

The avreich left, dazed by the large sum that he had been granted for free and puzzled by the wrath of this strange rav, whom multitudes of people came to see for no reason that he could fathom.

“Reb Avraham Fisch wasn’t angry at all,” one of his close chassidim explained to me. “This was how he worked. The avreich got an apartment, and Rav Fisch brought upon himself the derision he desired. Instead of viewing him as a generous baal chesed, the avreich would see him as a deranged kook.”

From where did Rav Fisch access the power to see into the distance, to give brachos and make promises that seemed to defy nature? The people who would frequent his home occasionally broached the topic, but he would usually change the subject, trying to create the impression that he was either crazy or moronic. On a few rare occasions he actually responded to these questions, explaining that his abilities came from his self-sacrifice in performing chesed for lonely Jews in need — Holocaust survivors who had been shattered by the war and wandered the streets of Tel Aviv without a soul to help them.

Rav Fisch would gather these homeless people from their benches and street corners. He often had to convince them to come up to his house and eat, since some of them had become so apathetic about life that it didn’t make a difference if they were hungry or full. Reb Avraham, the sole survivor of his own family, begged these despondent Jews to come with him; he let them bathe in his home and he served them hot meals. He took in even those who had lost nearly every vestige of humanity — those who were so neglectful of their hygiene that no one could stand near them.

They weren’t easy guests. Some insisted that they would sleep only in his bed or threatened him that they would not eat unless he ate out of the same plate. But Rav Fisch was prepared to endure any discomfort, as long as they would eat and allow themselves a little respite. He even purchased a record player, together with old chazzanus recordings, to make their stay with him a little more pleasant.

He once revealed, “If you act like me, you will also reach the levels I’ve reached.” Another time he said, “The gematria of chesed is 72, which is the greatest of the Names of Hashem,” hinting that his acts of chesed were what gave him entry into the club of Tel Aviv’s hidden tzaddikim of the previous generation.

Sometime after the war, Rav Fisch was walking through the streets of Tel Aviv on a winter night, when he found a Jewish man, nearly frozen from the cold, sleeping on a bench. Rav Fisch woke up the stranger and invited him to come and sleep in his home — but the only thing was, he was still homeless himself. He lived in a little niche beneath the staircase in an old building, as was barely able to fit another bed into that tiny space.

Several months went by with the two sharing the minuscule quarters, and then Reb Avraham was called up for IDF reserve duty. When he returned after a few days, his “houseguest” informed him that he was now the owner of that tiny niche. He commandeered Reb Avraham’s bed and agreed to allow Reb Avraham to sleep in the corner, if he would fit. But Reb Avraham held himself back from protesting the other man’s audacity. Years later, he made a comment to someone implying that the self-restraint at that time lifted his neshamah to sublime heights.

“You’ve Been Warned”

Not much is known about Rav Fisch’s life in Poland before WWII, except that his father was a Stutchiner chassid, and head of the town’s chevra kaddisha. He was the sole survivor of his family during the Holocaust, after Nazis burst into his home and shot everyone present — yet when they turned their weapons on him, the house suddenly went dark and he escaped through a window. He attributed his salvation to the blessing he received as a child from a righteous woman whose brachos were reputed to always be fulfilled.

Between flight and eventual incarceration, Reb Abraham somehow survived, eventually making his way to Eretz Israel, where he married Fraidel, the daughter of Rabbi Yosef Aschendorf. Although he worked as a common laborer by day, at night he was part of a group of hidden tzaddikim who studied the Torah’s secrets with the “Sandlar” — the Holy Shoemaker, Rav Moshe Yaakov Rabikov ztz”l.

Reb Avraham was also closely connected to Rav Aharon of Belz ztz”l, and used to serve as shamash in the Belz beis medrash. One Erev Shabbos a young avreich entered the beis medrash and heard someone reciting shnayim mikra v’echad targum in a tone that seemed to shake the Heavens. But as soon as Reb Avraham heard someone enter, he got up and began pacing the floor, mumbling to himself like a madman.

The intruder, however, was not amused. “You won’t fool me! Just a few minutes ago, you were reading the parshah with profound passion, and now you are trying to trick me into thinking you are crazy!”

Although any type of publicity caused Rav Fisch great distress, it was only a matter of time before the people started hearing about his special powers. One man — today a prominent communal activist — tells the story of his own father’s miraculous salvation.

“It happened about two years after the end of the war. My father was arrested by the British police on suspicion of collaborating with the underground, and although he was temporarily released on bail, the prognosis looked grim. In desperation, he went to Tel Aviv to see the Shoemaker, Rav Moshe Yaakov Rabikov, who listened to his tale of woe and said to him, ‘I can’t help you. I will send you to a certain nistar who will be shocked at the idea that you are coming to him for help. He will begin acting like a deranged man and saying bizarre things, but you must not leave him until, amid his ramblings, he gives you a brachah and promises you that you will be saved. Then you will know that you have been saved.’

“Rav Yaakov Moshe sent him to Rav Avraham Fisch’s home in Tel Aviv.

“Reb Avraham’s initial reaction was one of shock. Who knew about his involvement in spiritual matters? But he quickly recovered and, indeed, he began babbling and gesturing wildly. My father listened carefully to everything he said, and then suddenly, amid the blabber, he heard the strange man say, ‘An angel will come and confuse the judgment in your favor.’

“Hearing those words, my father turned to leave; but then Reb Avraham apparently realized that his visitor had heard the promise of salvation he slipped into his ramblings. Reb Avraham moved closer to him and warned, ‘Yungerman! Woe be to you if you publicize my name or send other people here. You have been warned!’

The Revelation

Those who were close with Rav Fisch knew he was not just a mystic, but a master talmid chacham who had developed ingenious methods of ensuring that others would know nothing about the scope of his Torah knowledge. He always insisted that he was a simple laborer, a man with no particular knowledge or wisdom of his own.

Rav Yehuda Zev Leibowitz, a mekubal who passed away about two years ago and who, like Reb Avraham, was childless, attested that Reb Avraham knew all of Maseches Eiruvin by heart, with all its intricacies and commentaries — one of the most difficult masechtos in Shas. Of course, those who knew Reb Avraham personally would have had difficulty believing this; he successfully projected the image of a person who lacked even an iota of Torah knowledge.

In fact, no one was ever able to find a single sefer in his house, other than a siddur and, occasionally, a volume of Mishnayos from Seder Zera’im. Rav Yehuda Segal of Tel Aviv once revealed that, according to Kabbalah, it is recommended for childless people to learn Seder Zera’im since they have no zera (offspring) of their own. One day, someone asked Reb Avraham if that was the reason he had this particular sefer in his possession — and the sefer disappeared from his table thereafter.

Who discovered this hidden tzaddik? Who was the person who caused so many Jews to visit his home? Some say that Rav Yisrael Abuchatzeira, the Baba Sali ztz”l, sent his gabbai, Rav Eliyahu Alfasi, to Reb Avraham to bring about salvations for certain people. Before his own death, the Baba Sali revealed to his followers a Heavenly decree that Rav Fisch would take his place with the power to bless and bring salvations to Jews.

And indeed, after the Baba Sali’s passing, people began flocking to Rav Fisch; he no longer hid, opening his doors wide to the entire spectrum of the Jewish People.

The Simple Truth

Rav Fisch always displayed a preference for simple people with pure, innocent faith. He used to say that those people would be saved from their troubles more easily, since they didn’t try to understand his actions or investigate his ways; they simply had faith, and it was easy to bring down salvation for them from Shamayim. Sometimes, he would even point to a person coming into his home and remark to those sitting beside him that the newcomer would certainly receive the yeshuah he needed, since he was filled with pure faith.

Rav Fisch’s followers say it was the during the Melaveh Malkah seudah that the greatest mystical feats would occur. Many people would join him at this meal, some bringing their own specific foods. Often, the meal would restart several times, as groups of people came and went until the morning. Through it all, Reb Avraham would be standing there, dispensing brachos and good wishes and even uttering curses upon the enemies of the Jewish People — still making sure to use the language of a simpleton in his ongoing effort to conceal himself.

During these seudos, he would light many candles in honor of David HaMelech, flying into a temper if anyone touched the candles. He would spend a long time gazing at the flickering flames and murmuring unintelligible words. On those Motzaei Shabbos nights, many people received blessings and promises were fulfilled.

Reb Avraham had three golden goblets, and his regulars knew they contained some mystical secrets. “When I ordered the cup from a Jewish goldsmith, I asked that the cup and its base together weigh exactly 600 grams, not a drop more or less,” Rav Fisch once told me. But the goldsmith wasn’t able to make it so precisely, and Reb Avraham was very distressed; this interfered with his mystical, Kabbalistic intentions. “Then I realized it was a hint from Heaven that until the Final Redemption comes, there will not be anything perfect in the world; there will always be some deficiencies, as a sign of the exile that we are still enduring.”

At the Melaveh Malkah meals, he told over the same story about the Baal Shem Tov every week. Through this story, he sought to bring about yeshuos for everyone present, and for the people who visited his home all week long. There are several known versions of the story, but this is the version that Reb Avraham Fisch would relate:

In his youth, the Baal Shem Tov used to seclude himself in the Carpathian Mountains during the week, and he came home only for Shabbos and Yom Tov. Every day, he would immerse himself in a river that ran through the mountains, and even when the river was frozen, the Baal Shem Tov would break the ice to enter the water, emerging with slivers of ice clinging to his beard and peyos.

There was a young non-Jew in the area who used to go fishing in the river, and he noticed drops of blood on the ice at the riverbank every morning. The young fisherman watched the area and observed the Baal Shem Tov emerging from the river and standing on its icy surface. He watched as the Baal Shem Tov would attempt to lift his feet from the ice but find them frozen to the surface. The Baal Shem Tov would then forcefully pull his feet off the ice, tearing his skin and shedding the drops of blood that the fisherman would find frozen to the river’s surface every morning.

The fisherman took pity on the Baal Shem Tov and from then on placed hay on the river’s surface, on the spot where the Baal Shem Tov would emerge from the water. The Baal Shem Tov was pleased by his actions, and he called the fisherman and asked him what brachah he would like: for ample sustenance, for health and physical strength, or for longevity. The non-Jew, of course, asked for all three, and the Baal Shem Tov promised him what he asked for.

Years later, after the Baal Shem Tov had passed away, the fisherman himself would tell over this story. By that time, he had already lived to a ripe old age, he was still strong and healthy, and he had never lacked for anything in his life.

When Reb Avraham told this story, he would always conclude, with the evident love for his fellow Jews that constantly burned in his heart, “Now, there is a kal v’chomer. If this gentile deserved health, sustenance, and longevity, how much more so are Jews deserving of these things.”

Cooling off Gehinnom

Apart from the small monthly sum Rav Fisch and his wife Fraidel kept for their own sustenance, they gave away everything else to the poor and needy. As Rav Fisch never had children of his own, he made sure to provide financial assistance to hundreds of newlywed couples, specifically buying them a refrigerator. He would explain that after his death, he would certainly be sent to Gehinnom, and he hoped that the many refrigerators he had donated would cool off the fires of Gehinnom at least a bit. He also used to donate ovens to impoverished newlywed couples, claiming that there is also a Gehinnom of ice, and the ovens might help bring him a small amount of warmth there.

He donated a large number of sifrei Torah to many shuls, calling them the “seforim of shalom bayis,” since he routinely hired sofrim who were experiencing shalom bayis difficulties due to their lack of parnassah. Reb Avraham did not pressure the sofrim to finish their work, nor did he set deadlines for them; he wanted to be able to pay them a fixed monthly salary, regardless of how much progress they had made.

Furthermore, he had two additional sifrei Torah written for the Jewish People: one for rectifying errant souls, and another for souls who knew no peace in this world. Exactly how Rav Fisch went about making these rectifications on Jewish souls will remain a secret forever, but we do know that in addition to the Torah scrolls, he would wear the clothing of people who had passed away, so that they would merit a portion in the World of Truth.

Last Will

Rav Fisch shared an esoteric, multifaceted connection with the Premishlaner Rebbe of Bnei Brak shlita, having shared many cryptic conversations during the Rebbe’s numerous visits to Reb Avraham’s home in south Tel Aviv. I was privy to some of those conversations myself, as I often accompanied the Rebbe on those visits.

I often heard Rav Fisch speak of his own demise. He pleaded with his followers that he should be buried in Tzfas, in a plot he had purchased many years before. Since he had no children of his own to carry out the charge, he made sure everyone else knew of this wish.

“If I die on a Friday,” he would emphasize, “and it’s almost Shabbos, just bury me in a hurry. Make sure I get to Tzfas, even if it means that I have to be brought there in a garbage truck. And if it’s almost Shabbos, throw me into the grave even without covering it.”

Incredibly, that’s just about what happened. Rav Fisch passed away in Jerusalem — where he spent his final few weeks — on Friday, 13 Elul 1998. As per his instructions, the funeral sped away to Tzfas, but since Reb Avraham did not have an established chassidic court, no one knew exactly who would be accompanying him on his final journey or what vehicle would be used to transport the niftar.

Meanwhile, six of us set out in a car from Bnei Brak with the Premishlaner Rebbe, hoping we could somehow spot the vehicle carrying Reb Avraham to his final rest. We drove for nearly an hour, but the Rebbe instructed us to keep going, although Shabbos was soon approaching and the car carrying the niftar was, in all likelihood, already far to the north of us. After all, whoever would be conducting the funeral also had to worry about getting back before Shabbos.

Suddenly we were flagged down by a van parked on the shoulder of the highway, stranded by a flat tire. We stopped and discovered that this was the very car that was transporting Rav Fisch! The Rebbe got out, and a quick headcount showed that we made up exactly a minyan — the Rebbe, his six companions, and the three passengers in the car carrying the body. The door opened, and the Rebbe recited Kaddish for the man whose entire life was shrouded in mystery.

The tire was then repaired, and the van sped off for the Friday burial in Tzfas.

“Tzfas has good air,” I once heard him remark with a mysterious smile. “When I want to relax, I’ll come out and take a stroll in the pleasant breeze.”

Years ago Reb Avraham purchased burial shrouds for himself, and he would show them to the many visitors to his home. He would explain that Mashiach will begin his journey in the Galil, and it is therefore a good idea to experience techiyas hameisim in Tzfas. And the levayah and burial took place exactly as he had said many times throughout his life. He was buried during the final few minutes before Shabbos, and the funeral participants rushed to leave the cemetery before Shabbos, just as he had predicted.

The inscription on his tombstone notes that he used to tell anyone who needed a yeshuah to recite three times the stanza of “Racheim b’chasdecha” from Tzur Mishelo in the Friday night zemiros. This, he said, would help restore the glory of the Shechinah.

Rav Fisch didn’t leave children, but before he died he left his followers with another legacy, perhaps his biggest secret: to stretch oneself way beyond one’s imagined capacity, to bestow good on others even beyond one’s own abilities, and to thereby purify one’s own neshamah and bring the world to heightened holiness.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 488)

Oops! We could not locate your form.