In the Driver’s Seat

| November 2, 2021While parenting challenges will arise, we can stay in the driver’s seat and give our teens the gift of an empowered parent

Illustrations: Karen Keet

When Chavi’s kids were young, answering their questions was easy: “How do birds stay up in the air?” “Why is candy bad for our teeth?” She could swing that.

But once her oldest daughter Shevy became a teen, she floundered. When Shevy complained about her school’s technology rules, or challenged her with questions on tzniyus, Chavi felt inadequate and helpless.

Rina’s teenage daughter Sari didn’t have an easy time academically, and the high school social scene was challenging for her as well. Some days were good, but other times Sari came home in a terrible mood.

When this happened, Rina would immediately try to find solutions to the problems. But Sari would be in no mood for such a conversation, and invariably the communication would end in disaster — with both of them feeling bad about Sari’s difficult day.

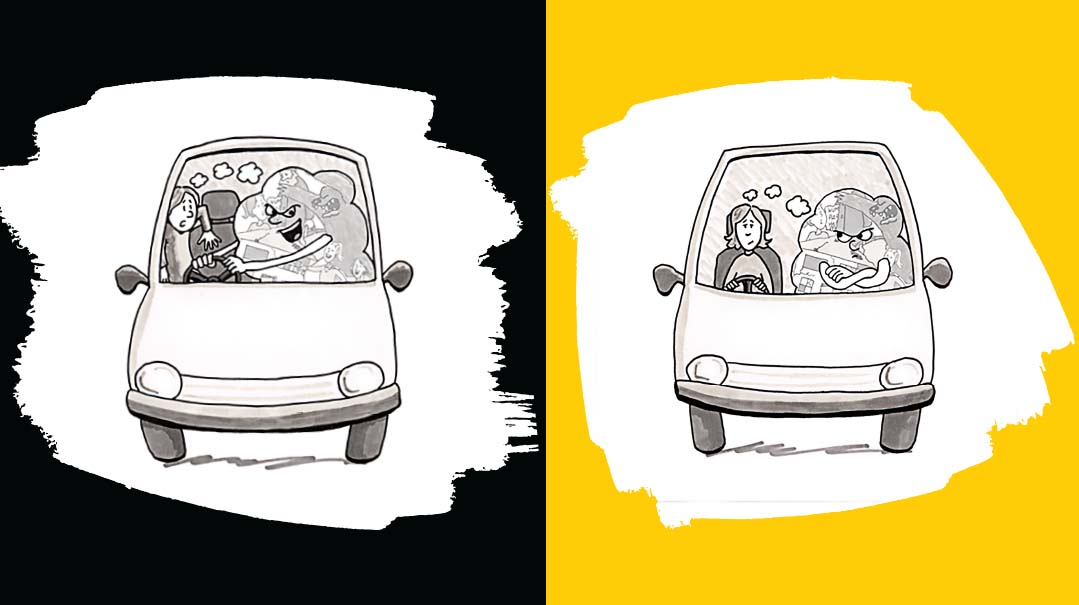

Shoshi’s son Ari had always been a handful. As he got older, she felt less and less confident dealing with his outbursts. When Ari would begin shouting or talking aggressively, Shoshi would go into “passive mode,” allowing him to do or have whatever he wanted in order to “keep the peace.” She knew she was allowing Ari’s aggression to control her, but she had no idea what to do about it.

“The first thing every parent needs to know is that building positive communication and a deep relationship with teen children is a genuine challenge,” says Mrs. Deborah Saunders, a therapist and parenting coach in Manchester, UK. “But what parents also need to know is that it’s absolutely possible.”

Mrs. Saunders gives workshops to parents, showing them how to develop positive relationships with their teenage children. The techniques she teaches are an outgrowth of her work with teenage clients in her private practice.

“Topics like self-regulation, processing moods, trusting yourself, resilience — these were tools and skills I was guiding teens in, over and over, in individual sessions,” she says. “I figured, why not collate the material and present it to a broader audience? That way, every teen can access these important life skills and dramatically enhance their emotional well-being.”

That was the impetus for her recently released book Teen Power for Girls — 9 Secrets to Confidence and Success (Adir Press 2021). At the same time, Mrs. Saunders began delivering the material in schools, workshop-style. The more she worked with the teen population, the more she heard from their parents — their questions, their concerns, their worries.

Eventually, Mrs. Saunders began coaching parents in how to best communicate with their struggling teens. “That’s when I thought, again, that instead of giving over the same information over and over to individual clients, I should present it as a course, to groups,” she says. “Also, courses would be more accessible to everyone. A teen shouldn’t have to be in crisis and come for therapy for the parents to be able to learn effective techniques to improve their relationship.”

Deborah’s course focuses on topics such as emotional well-being, stress management, communication, and resilience building. She calls it Inside-Out Parenting, and it’s based on the idea that parenting isn’t about the children and their behavior — it’s always about where parents find themselves. Her main objective is to help parents bridge the space between their children and themselves.

“It’s a mind-shift to realize that a parent can feel stressed out over a calm child, or conversely, remain empowered even when a child is in crisis,” Deborah explains. She brings the analogy of viewing each person as an individual house. “If I’m in my own house, I can access support, guidance, and self-care where necessary in order to have what to give outward,” she says. “However, if I jump into someone else’s house — their moods, emotions, difficulties — and try to control their behavior or actions, it backfires. We’re both disempowered. We need to separate our needs from our child’s, our experience from theirs.”

Very often, she finds, parents see a transformation in their child’s attitude, mood, or behavior simply from making this shift — when their child realizes he can’t “hook” the parent anymore into playing his game. Even if that isn’t the case, there’s internal empowerment. It’s a realization that the parent’s well-being is completely independent of the child’s and can’t be intercepted. And this, she explains, gives the parent the strength and calm to access their inner resources and handle the child in the best possible way.

“We don’t need to get entangled in our teens emotions or difficulties — be it anxiety, aggressiveness, insecurity, anger, or whatever they happen to be going through,” Deborah says. “It’s not that we don’t care. It’s that stepping back and becoming empowered helps both us and our children to handle it.”

Deborah finds that parents will often call her up about a child suffering from anxiety, asking how they can help, or if Deborah could meet with their child. But what Deborah hears is waves of the parent’s own anxiety coming through the phone. What the parent needs to do is own her worry and anxiety, instead of suppressing it and putting everything onto the child.

“First become aware of yourself, and then reach out and support your child from a place of strength,” she says.

As a mother of teens herself, Deborah emphasizes, “Nothing that I teach is intended to undermine how challenging it can be to raise teens. I’m not here to say ‘it’s not hard, just go back in your house, and you’ll be fine.’ It is hard seeing a child suffering from anxiety or going through a challenge. But if a parent can own that they’re finding it challenging — if they can separate their own feelings from their child’s and say ‘I’m having a hard time, I’m in pain watching my child in pain’ — they’ll be grounded. That’s a place from where they can reach out for support for themselves and then be there for their child in a powerful and effective way.”

Acknowledge and Accept

Deborah coaches parents to change their approach to parenting with a four-step process, which she summarizes as WATCH: What (are you feeling), Accept, Trust, and Choose.

“W stands for What do I feel, and it involves just noting your inner state during interactions with your children. Is it tension, worry, anxiety, stress? Remember that between you and your child is a space, and whatever you experience is your own ‘stuff,’ ” she emphasizes. “It’s only by acknowledging and owning our feelings that we can move forward to the next stage, to accept them.”

A stands for Accept — to let it exist. “Give yourself permission to feel whatever it is that you’re feeling, even if it’s a strong reaction, such as panic. It’s okay. Give yourself space to feel it without judgment. Whatever we feel is okay, as long as we own it.”

Simply becoming aware of and accepting our feelings is a big step toward empowered parenting, because it means we take ownership of our inner world and realize that our child isn’t controlling our emotional state. In addition, it means that our child’s misbehavior, inner turmoil, or bad mood doesn’t need to affect our inner calm.

“Not taking the child’s situation or behavior personally is huge,” Deborah says. “When I explain this to mothers, I literally feel the difference in the room. I watch their shoulders relax as the tension leaves them.

“We tend to blame ourselves when our child isn’t in a good place,” Deborah continues. “But blaming ourselves means our self-acceptance is dwindling — and that’s when we go into panic mode. Instead, we have to remember that our child’s behavior doesn’t threaten us as a person. We’re valuable irrespective of what’s going on with our child. Knowing that our children can’t threaten our unconditional worth, we can then face their challenges head-on and move in the right direction.”

When Rina learned about this concept, she realized that her reaction to Sari having a hard day at school was actually triggered by memories of her own social struggles in high school. Now, instead of getting sucked into her own anxiety and distress, she lets herself notice: “I’m feeling triggered right now by Sari’s bad mood. I accept that I’m feeling tense and upset because of this.”

Although it may seem counterproductive to acknowledge difficult feelings, what actually takes place is a transformation — instead of Rina trying to rid herself of the burden of her own supressed emotions by jumping into problem solving (which Sari doesn’t appreciate), she accepts her own feelings and is then able to focus on moving forward despite them. She can focus on listening to Sari talk and try to understand her, while being aware of the fact that it’s challenging for her.

Because she has this awareness, Rina takes time out for herself after Sari’s finished talking, to meet her own needs and address her own sadness. The result? Rina acknowledges, accepts, and addresses her own feelings — and Sari feels validated and understood, instead of pressured to problem solve and “feel better” so her mother can feel better, too.

The Trust Issue

“The next step, ‘T’, stands for Trust, which encompasses a few things,” Deborah explains. “We need to have trust, first and foremost, in Hashem — that He’s our Partner in parenting this child. We can hand over that weighed-down feeling and allow Him to worry about the bigger picture, while we simply do our best at each step of the journey.”

“Equally crucial is trust in ourselves as parents, although all of us experience moments of self-doubt. If Hashem put us in this role, we need to believe we’ve been given the resources, resilience, and inner wisdom to parent our children. Then we can go on, in the next step of the process, to make effective decisions and carry them through — because we trust our instincts to help us make the right choice.

“When we’re empowered in this way, we teach our children to tap into their own inner strength, wisdom, and resilience. Rather than interacting with them plagued by self-doubt and insecurity — which will most likely trigger them to feel that way too — we model serenity and self-acceptance, and that’s what they pick up.”

When Chavi learned to trust herself, she experienced a huge shift in her parenting. She was able to discuss difficult topics with Shevy, trusting her inner wisdom to help her find the right words — and knowing when it was time to reach out for guidance from expert mechanchim.

Shevy sensed her mother’s confidence, and this helped her feel more secure; she realized her questions couldn’t “shake” her mother’s inner calm. That, in turn, made her less challenging and more curious. She was beginning to access her own inner peace — thanks to Chavi working on shifting from a self-deprecating perspective to an empowered one, trusting in Hashem that He gave her all the wisdom and tools she needed to parent her daughter.

Make Your Move

Finally, the last step is Ch — Choice.

“Once we’re in a more empowered frame of mind, we’re able to think: What is my next best action,” Deborah says. “We look at the situation we’re in, and we assess what’s the best piece of hishtadlus we can do right now, as a parent. Is it to make an appointment with a mental health professional? To wait for a calm moment and talk to our child ourselves? Is it to take a personal ‘time out’ and meet our own needs?”

Unless a child is in immediate danger, Deborah advises going slow. “The urgent need to fix, fix, fix — that’s anxiety,” she says. “Commit to making a change, whether practical or in the way you communicate with your teen. Don’t pressure yourself to solve everything at once. It’s better to go forward slowly, than rush and get it wrong.”

She gives the typical example of a teen child coming home very late at night.

“The key is to think what can I do as a responsible parent and not what needs to happen,” she says. “We can only control our next move; we can’t control our teen’s choices. The sooner we let go of that, the better!”

That move might be to firmly and calmly set a curfew. Deborah reiterates that effective teen communication isn’t necessarily about saying what the child wants to hear — but it is about talking to them from a calm and grounded place, remembering that they deserve respect as Hashem’s child, no matter how they’re behaving.

“If the mother is in a difficult space with her own feelings — and she isn’t aware or accepting of that — she’ll blame the feelings on the child and shout at or criticize them for coming in late and making her anxious,” she says. “What she doesn’t realize is that there’s no way that communication will be effective. Her child will simply hear noise and tune it out.”

Shoshi was able to be honest with herself and admit she felt threatened when her son Ari shouted, and that she was uncomfortable with his aggression. Then she was able to tap into her inner resources and mindfully get help to deal with the issue.

Now, she’s regained control of the situation by firmly and confidently asking Ari to lower his voice, by remaining supportive of his feelings, but not submitting to his demands, and by continuing to access support from outside sources when she needs it, or seek higher-level intervention should the situation ever become more serious.

Nothing like a Parent

Being “in the trenches,” working with the teens themselves, gives Deborah — and the parents she coaches — a unique insight into their world.

“One thing that every parent should know is just how important they are to their teenage children,” Deborah says. “Even if their child brushes them off, or doesn’t show interest — deep down, they’re craving a relationship.”

In the course of her conversations with her teenage clients, boys and girls, this has become very apparent. One question she frequently asks her clients is, “If you have a problem, who do you want to talk to about it?”

“I’m amazed at the high percentage of teens who respond that they would want to talk to their parents about stuff, but they won’t risk it if they feel their parent will try to take control or judge them.” Deborah says. “In reality, that’s what they’re craving. Although it often looks like they choose to confide in their friends — who provide the ‘pseudo’ validation and acceptance in the short term — even teens themselves realize it’s not enough. At the end of the day, there’s no replacement for a parent.”

WATCH in Practice

- What are you feeling?

How often do we react strongly to something, without even realizing that our reaction is rooted in insecurity? Becoming aware of what we’re feeling is vital. Ask yourself, “What feelings are being triggered in me by my child / his behavior?”

- Accept

Don’t judge or justify what you’re feeling. Allow yourself to feel whatever emotions come up, and realize it’s okay to be wherever you are right now. It’s not silly or weak, and you don’t need to force the feelings away. Let yourself be there. Remember you’re a worthy, valuable person, and nothing can change that.

- Trust

Trust that you have the resilience and wisdom to parent your children. Trust yourself to deal with the aspects within your control (your response), and trust Hashem to hold the things that are beyond your control (your child’s behavior and external circumstances, past and future). Trust that your child has his own strengths and wisdom given to him directly from Hashem. He can handle challenges too.

- Choose

Be careful not to react automatically to your feelings. Your power is in your choices. No matter what’s going on with your child or what your emotional situation is, you can choose how you want to respond. The key is to focus on the situation as it stands right now. Is there any action you can take which might help you reach a calmer space, for example: taking a walk, listening to music, speaking to a supportive friend or mentor? Is there any action you can take to help your child in this situation? If you knew that you had the power inside you to choose well, what would be your next step?

Teen Talk

Struggling to initiate and maintain effective conversations with your teens? Deborah offers tips:

- Support, don’t sort. You can be fully present for your child without jumping in to solve their problems for them. When a teen comes home after getting in trouble in school, a parent may be tempted to immediately instruct her how to behave the next time. Resist the urge, and instead try to draw on her own resources. “Teens loves asserting their independence,” Deborah says. “When a teenager enters my office for counseling, I tell her: I can’t do this without you. I only occupy one half of the room — the other is totally in your control.” There’s a tremendous energy in teens that we can tap into by respecting their identity as their own person and giving them the independence to find solutions on their own.

- Ask permission to advise. When a teen is going through a challenge, she’s not necessarily in a place to hear what the parent has to say. Deborah suggests asking her, “I have some ideas for you — would you like to hear them?” Put the ball in the teens’ court.

- Be clear, direct, and keep it short. When you do have something important to tell your child, such as a rule or boundary, say it in a single sentence using an assertive tone. The child should know exactly what you’re saying, instead of hearing you go round in circles or hedging the point apologetically.

- Give them space. It’s something Deborah hears from teens over and over: When I’m in a bad mood, I just want my space. By respecting your child’s need for space and independence, you’re creating a relationship in which you’ll be able to communicate and set boundaries where necessary.

- You don’t have to be perfect. If you find yourself feeling disempowered, it’s okay to say, “Sorry, I’m feeling a little stressed now, and I overreacted. Let’s try again.” It’s a huge parenting moment when we show our child that it’s okay to be human, catch ourselves, and get back on track.

- Keep it light. Teens shy away from intensity. Draw on humor and lightness when discussing things with teens.

(Originally featured in Family First, Issue 766)

Oops! We could not locate your form.